中国组织工程研究 ›› 2024, Vol. 28 ›› Issue (13): 2098-2104.doi: 10.12307/2024.142

• 干细胞综述 stem cell review • 上一篇 下一篇

影响肌腱干细胞分化的因素

逯静薇1, 吕可馨1,蒋 莉1,陈艺萱 1,石厚银 2,李 森2

- 1西南医科大学体育学院,四川省泸州市 646000;2西南医科大学附属中医医院,四川省泸州市 646000

-

收稿日期:2023-03-08接受日期:2023-04-22出版日期:2024-05-08发布日期:2023-08-29 -

通讯作者:李森,男,博士,主任医师,硕士生导师,西南医科大学附属中医医院脊柱肿瘤科一组,四川省泸州市 646000 -

作者简介:逯静薇,女,1998 年生,河北省邢台市人,汉族,西南医科大学在读硕士,主要从事肌腱损伤相关研究。 -

基金资助:四川省科技计划(2022YFS0609),项目负责人:石厚银;泸州市政府-西南医科大学科技战略合作项目(2021LZXNYD-J10),项目负责人:李森;西南医科大学应用基础研究项目(2021ZKMS050),项目负责人:李森

Factors affecting differentiation of tendon stem/progenitor cells

Lu Jingwei1, Lyu Kexin1, Jiang Li1, Chen Yixuan1, Shi Houyin2, Li Sen2

- 1School of Physical Education, Southwest Medical University, Luzhou 646000, Sichuan Province, China; 2Affiliated Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital of Southwest Medical University, Luzhou 646000, Sichuan Province, China

-

Received:2023-03-08Accepted:2023-04-22Online:2024-05-08Published:2023-08-29 -

Contact:Li Sen, MD, Chief physician, Master’s supervisor, Affiliated Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital of Southwest Medical University, Luzhou 646000, Sichuan Province, China -

About author:Lu Jingwei, Master candidate, School of Physical Education, Southwest Medical University, Luzhou 646000, Sichuan Province, China -

Supported by:Sichuan Science and Technology Program, No. 2022YFS0609 (to SHY); Luzhou Municipal Government-Southwest Medical University Joint Project, No. 2021LZXNYD-J10 (to LS); Applied Basic Research Project of Southwest Medical University, No. 2021ZKMS050 (to LS)

摘要:

文题释义:

肌腱干细胞:是具有自我更新、克隆和多向分化潜能的独特细胞群,位于主要由细胞外基质组成的生态龛中。肌腱干细胞的正向分化有助于组织工程的应用。肌腱病:是一种肌肉骨骼疾病,以疼痛和活动能力下降为特征,伴有胶原蛋白紊乱和血管增生的病理变化。

背景:肌腱病是一种肌肉骨骼疾病,以疼痛和活动能力下降为特征,伴有胶原蛋白紊乱和血管增生的病理变化。肌腱病常易发生在运动员、体力劳动者和老年人身上。肌腱病的机制之一是 “失败的愈合反应”,而导致失败愈合反应的部分原因是肌腱干细胞的错误分化。

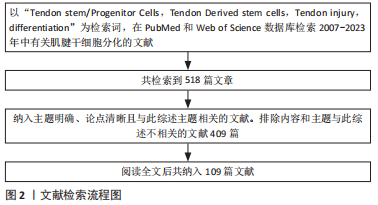

目的:通过阅读相关文献,介绍肌腱干细胞的特性,总结影响肌腱干细胞向肌腱细胞分化的因素以及导致肌腱干细胞错误分化(分化为脂肪细胞、骨细胞和软骨细胞)的因素,同时阐述肌腱干细胞在临床中的应用局限。方法:检索PubMed及Web of Science数据库中相关文献,检索词为“Tendon Stem/Progenitor Cells,Tendinopathy,Tendon injury,differentiation”,通过阅读筛选出相关文献,最终纳入109篇文献进行结果分析。

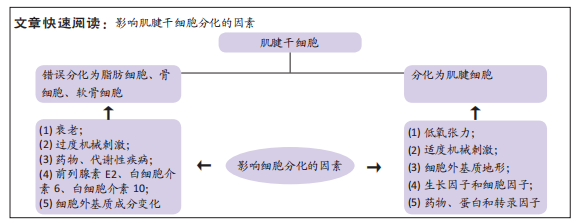

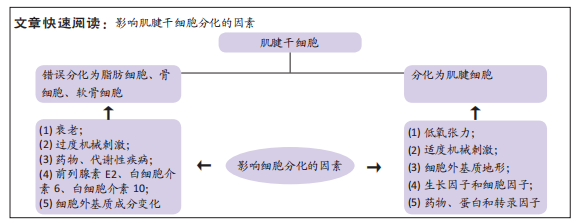

结果与结论:①肌腱干细胞是可以自发分化为肌腱的一种干细胞,它具有自我更新、克隆和多向分化的能力,不同的外部条件作用于肌腱干细胞可以导致其向不同方向分化。调节肌腱干细胞命运的具体因素并不确定。当肌腱中的干细胞更新和分化出现异常时,会导致肌腱愈合失败,进而导致肌腱病。②衰老、细胞外基质成分的变化、过度的机械刺激、前列腺素E2和白细胞介素6以及白细胞介素10和一些系统性疾病可能对调控肌腱干细胞的错误分化有重要意义。③促进肌腱干细胞向腱细胞分化的可能有利因素有:一些生长因子和细胞因子、适度的机械刺激和细胞外基质的地形、低氧张力、药物以及某些转录基因和蛋白。④目前最为理想的治疗手段则是对内源性肌腱干细胞进行调节,或者外源性肌腱干细胞刺激内源性肌腱干细胞的增殖分化。⑤未来研究进一步了解调节肌腱干细胞错误分化的因素,可深入了解肌腱病的发病机制并找到治疗靶点,阐述诱导肌腱干细胞向肌腱分化则可促进其在组织工程中的应用。

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1556-0927 (逯静薇);https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4819-097X (李森)

中国组织工程研究杂志出版内容重点:干细胞;骨髓干细胞;造血干细胞;脂肪干细胞;肿瘤干细胞;胚胎干细胞;脐带脐血干细胞;干细胞诱导;干细胞分化;组织工程

中图分类号:

引用本文

逯静薇, 吕可馨, 蒋 莉, 陈艺萱 , 石厚银 , 李 森. 影响肌腱干细胞分化的因素[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2024, 28(13): 2098-2104.

Lu Jingwei, Lyu Kexin, Jiang Li, Chen Yixuan, Shi Houyin, Li Sen. Factors affecting differentiation of tendon stem/progenitor cells[J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2024, 28(13): 2098-2104.

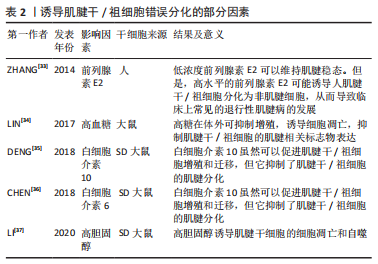

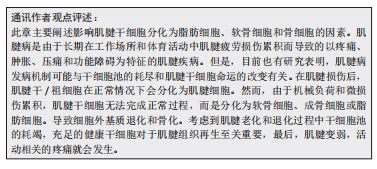

2.2 诱导肌腱干细胞错误分化的因素 众所周知,在慢性肌腱病的病理组织中不仅可以观察到血管化和胶原蛋白紊乱,还可以观察到软骨细胞和成骨细胞。除此之外,肌腱变性伴有黏液状蛋白沉积,还伴有炎症反应和疼痛[29]。一般观点认为,肌腱病是由急性创伤负荷、重复机械创伤或过度使用引起的[30]。但是,肌腱病的发病机制是复杂的,是由多种因素引起的。在肌腱病变过程中,外源性谱系细胞被激活,导致血管和神经向内生长,进而引起疼痛。与此同时,内源性肌腱干细胞也可以对信号做出异常反应并错误分化以代替细胞命运[31]。慢性肌腱病的致病机制之一是肌腱干/祖细胞错误分化为非肌腱细胞[32]。部分诱导肌腱干/祖细胞分化为非肌腱细胞的因素总结见表2,肌腱干/祖细胞错误分化的诱因包括衰老、细胞外基质成分的变化、过度的机械刺激和一些生物活性因素(炎症因子和细胞因子)[33-37]。此外,药物和代谢性疾病也是重要的诱因。

2.2.1 衰老 年龄相关性肌腱病与肌腱干/祖细胞的衰老密切相关,这表明衰老对肌腱干/祖细胞的功能产生了负面影响[38]。这可能会限制肌腱干细胞在肌腱损伤修复中的应用和组织工程中细胞来源的选择。除了干细胞的分化能力随年龄增长而下降,肌腱干/祖细胞向肌腱分化的能力也随年龄增长而降低。在许多动物模型和人类衰老的肌腱中,已经检测到许多非肌腱物质,如脂肪细胞和成骨细胞。除此之外,老化肌腱组织生物力学以及结构都发生变化。衰老肌腱组织临床表现为生物力学减弱,修复能力差以及易受损伤和断裂等[39]。

衰老肌腱干细胞中肌腱标记基因的表达减少,但脂肪生成标记的表达却增强了;此外,与年轻肌腱干细胞相比,衰老肌腱干细胞中的CD44表达水平更高,这表明受伤组织的愈合能力较差[40]。除了脂肪细胞增加外,P16在衰老肌腱干/祖细胞中也高表达。P16蛋白是老化细胞的标志物,可调节基因的表达[41]。根据最近的一项研究,在衰老肌腱干细胞中,胶原蛋白Ⅰ和肌腱相关的标记基因包括Scx、Tnmd和双糖链蛋白聚糖的表达减少,但P16的表达却明显上调。P16的上调影响了肌腱干/祖细胞的成腱分化能力。P16通过增强miR-217的转录,从而降低EGR1(EGR1是介导肌腱干/祖细胞分化的一种转录因子)的表达,抑制肌腱干/祖细胞的腱性分化[42]。针对年龄相关性肌腱病,可以采用抑制Rho相关蛋白激酶1(recombinant Rho associated coiled coil containing protein kinase 1,ROCK1)来治疗。ROCK1是细胞衰老的关键参与者,ROCK1的升高会阻碍肌腱愈合。ROCK 抑制剂 Y-27632的应用不仅使老化肌腱干/祖细胞变得更柔软,而且使它们的细胞体积减少,且细胞骨架也类似于年轻肌腱干/祖细胞[43]。

2.2.2 细胞外基质成分变化和过度机械刺激 细胞外基质成分的变化和异常的机械负荷都可能导致肌腱干/祖细胞的错误分化。干细胞龛是由细胞、细胞因子和细胞外基质组成的三维结构,而肌腱干/祖细胞的龛主要由细胞外基质蛋白调节[15],所以,肌腱干/祖细胞位于主要由细胞外基质蛋白组成的壁龛中。如果细胞外基质的组成发生变化,很容易导致肌腱干/祖细胞向非肌腱分化。细胞外基质由胶原纤维和蛋白多糖组成,其中构成细胞外基质的两种小蛋白多糖双糖链蛋白聚糖和纤维调节素在肌腱中高度表达,双糖链蛋白聚糖和纤维调节素基因的缺失会损害肌腱干/祖细胞的分化 [15,44]。

在BI等[15]的实验中,那些缺乏双糖链蛋白聚糖和纤维调节素基因的小鼠肌腱中发生了异位骨化,同时软骨细胞标记物也增加,其原因之一是由于细胞外基质成分的变化导致肌腱干细胞生态位的平衡被破坏。当肌腱干/祖细胞中双糖链蛋白聚糖和纤维调节素缺失时,会刺激骨形态发生蛋白2的升高,而骨形态发生蛋白2通过Smad1-Smad5-Smad8途径增加Runx2的表达,从而促进骨形成。

虽然机械负荷是肌腱发育的必要条件,但异常负荷会改变细胞外基质的组成和细胞因子的活性,从而破坏生态位的平衡,引起肌腱损伤[45]。过度机械刺激是钙化性肌腱病发生的原因之一[46-48]。在一项体内研究中,NIE等[49]发现,对从大鼠髌骨肌腱中分离出的肌腱干/祖细胞施加8%的单轴机械拉伸负荷,导致其向脂肪细胞、软骨细胞和骨细胞分化。在这项研究中,机械应力通过激活哺乳动物雷帕霉素信号通路诱导肌腱干/祖细胞向非肌腱系分化。

在体外实验中,对大鼠肌腱干/祖细胞施加8%的单轴机械张力,通过Wnt5a/Wnt5b/JNK信号通路诱导肌腱干/祖细胞分化为成骨细胞。除此之外,还观察到脂肪相关基因(PPARgamma260)的mRNA表达增加[50]。然而,另一项研究表明,Wnt5a-RhoA途径也可以介导肌腱干/祖细胞向骨细胞的分化,在体外,用体积分数2%单轴机械刺激3次(3,7,10 d)大鼠肌腱干/祖细胞后发现,Runx2、Alpl和Col2a1(成骨标记物)显著增加;除此之外,在单轴机械张力刺激下,RhoA(一种成骨调节剂)在大鼠肌腱干/祖细胞中被激活;同时,单轴机械张力上调了Wnt5a的mRNA表达,这表明单轴机械刺激通过Wnt5a-RhoA通路介导肌腱干/祖细胞向骨细胞分化[51]。

2.2.3 前列腺素E2、白细胞介素6及白细胞介素10 肌腱病的发病机制之一是过度的机械负荷,这导致了前列腺素E2的上升。而过量前列腺素E2的上升导致肌腱干/祖细胞的错误分化,从而导致肌腱病的发生。前列腺素E2是由花生四烯酸通过环氧化酶合成的,它是引起肌腱疼痛的炎症递质。前列腺素E2以剂量依赖的方式影响腱细胞的增殖和胶原蛋白的产生,而高浓度的前列腺素E2会阻止腱细胞的增殖和胶原蛋白的合成[52]。有研究建立了一个大鼠跑步机模型,对大鼠进行为期1周的训练(每日15 min,每周5 d),最后处死大鼠,去除其髌骨和跟腱,然后对肌腱样本进行检查,发现重复的机械负荷引起了肌腱中前列腺素E2的增加,前列腺素E2浓度的增加诱导了肌腱干/祖细胞的成脂和成骨分化;同时,在细胞实验中显示,单一的机械负荷不会引起肌腱病,而重复的机械负荷会导致肌腱病的发生,说明前列腺素E2的增加会减少细胞的增殖,阻碍胶原蛋白的合成[53]。

除了前列腺素E2外,白细胞介素6和白细胞介素10也影响肌腱干/祖细胞的分化。肌腱干/祖细胞在肌腱愈合过程中至关重要,而炎性细胞因子可以通过影响肌腱干/祖细胞的生物学效能而影响肌腱愈合的速度。白细胞介素6,10在炎症反应期显著上调,在此期间,白细胞介素6和白细胞介素10虽然促进肌腱干/祖细胞的增殖,但阻碍了肌腱干/祖细胞向腱细胞的分化[35-36]。研究发现白细胞介素6与从大鼠跟腱中分离出来的肌腱干/祖细胞共同培养可以促进肌腱干/祖细胞的增殖;然而,白细胞介素6通过激活肌腱干/祖细胞中的JAK/Stat3信号通路,抑制了成纤维分化。同样地,白细胞介素10促进了肌腱干/祖细胞的增殖和迁移;然而,它也通过激活肌腱干/祖细胞中的JAK/Stat3信号通路而抑制肌腱细胞标志物的表达。此外,有研究表明,白细胞介素1β也会阻碍肌腱干/祖细胞向肌腱系分化,并有可能不可逆地破坏肌腱的形成,因此,抑制白细胞介素1β将促进肌腱干/祖细胞在肌腱修复中的功能[54]。

2.2.4 药物 糖皮质激素是经常使用的治疗肌腱病的方法之一,虽然它可以在短期内减轻疼痛和改善运动功能,但其长期效果仍有争议[55-56]。地塞米松是一种糖皮质激素,通过抑制肌腱干/祖细胞向腱细胞的分化而降低肌腱的修复能力,进而增加肌腱断裂的风险。有研究将不同浓度的地塞米松注射到人肌腱干/祖细胞中,发现所有浓度的地塞米松都阻碍了胶原蛋白Ⅰ的合成,此外,高浓度的地塞米松诱导人肌腱干/祖细胞分化为脂肪细胞、软骨细胞和成骨细胞[57]。Scx是肌腱干/祖细胞分化为腱细胞的一个重要转录因子。CHEN等[58]发现,地塞米松与糖皮质激素受体结合后抑制了肌腱干/祖细胞中Scx的蛋白表达,同时,地塞米松则抑制了胶原蛋白Ⅰ和Tnmd的表达。这表明, 地塞米松抑制了 肌腱干/祖细胞向腱细胞的分化,表明地塞米松通过耗尽干细胞池来改善肌腱病,这导致肌腱更容易断裂。

非类固醇抗炎药也是治疗肌腱病的常用方法之一,它通过抑制环氧化酶的合成来缓解疼痛,但其疗效仍有争议[59]。ZHANG等[60]研究了塞来昔布对肌腱干/祖细胞的增殖和分化的影响,用环氧化酶2抑制剂塞来昔布处理肌腱干/祖细胞,发现肌腱相关基因Scx、Tnmd和胶原蛋白I明显减少,但对肌腱干/祖细胞的增殖没有影响。

2.2.5 代谢性疾病 糖尿病和高胆固醇患者更有可能患肌肉骨骼系统的疾病,如肌腱病。高血糖和高胆固醇会影响肌腱干/祖细胞的分化。已经证明,与非糖尿病患者相比,糖尿病患者更容易患肌腱病[61-62]。

首先,高血糖会阻碍肌腱干/祖细胞的增殖并诱导其凋亡;除此之外,高血糖不仅抑制了肌腱干/祖细胞的干性,而且还下调了肌腱标志物的表达,包括Ⅰ型胶原和Scx [34]。在慢性肌腱病变的过程中,会出现异常的血管增生,如在糖尿病大鼠的跟腱中发现的情况 [63]。其次,在糖尿病肌腱病变中观察到肌腱钙化,高血糖通过降低蛋白多糖的水平导致肌腱钙化[64]。有研究者建立的大鼠糖尿病模型中成骨标志物骨保护素和骨钙素髌腱组织中呈阳性表达[65]。而体外实验显示,患有糖尿病大鼠的肌腱干/祖细胞更多地分化为软骨细胞。最后,糖尿病患者容易发生肌腱病变或肌腱断裂,主要原因是高浓度的葡萄糖导致基质金属蛋白酶的表达增加,基质金属蛋白酶是一种调节细胞外基质重塑的降解酶。在高葡萄糖浓度的条件下,基质金属蛋白酶9和基质金属蛋白酶13的mRNA表达上升,当它引起胶原蛋白的降解,进而破坏了细胞外基质的平衡。总之,高糖可抑制肌腱干/祖细胞细胞增殖,诱导细胞凋亡,抑制体外肌腱干/祖细胞肌腱相关标志物的表达。这些发现可能揭示了糖尿病肌腱疾病发病机制的一些病理机制。

除糖尿病外,高胆固醇也会增加肌腱病的风险。高胆固醇性肌腱病的发病机制与肌腱干/祖细胞有关。一是高胆固醇增加了活性氧的产生,导致氧化应激(氧化应激诱导细胞凋亡),从而导致肌腱病变。其次,高胆固醇通过激活活性氧中的核转录因子κB信号通路,抑制了肌腱干/祖细胞向腱细胞的分化[66]。此外,LI等[37]发现高胆固醇不仅抑制肌腱干/祖细胞的增殖和迁移能力,而且通过激活活性氧中的AKT/FOXO1信号通路促进肌腱干/祖细胞的凋亡和自噬,从而导致肌腱病的发生。

2.3 调节肌腱干细胞向肌腱细胞分化的因素 肌腱病通常会有严重的疼痛,给社会带来巨大的经济负担。尽管再生医学在过去的十几年中取得了一定的成就,但由于肌腱组织细胞密度低和血管较少而导致肌腱自然愈合能力不佳。因此,对于肌腱损伤的治疗,仍旧有一定的挑战。组织工程的发展为肌腱样组织再生带来了希望。组织工程旨在同时利用细胞和材料,以合适的生化和物理化学因素,恢复受损组织的生理功能。

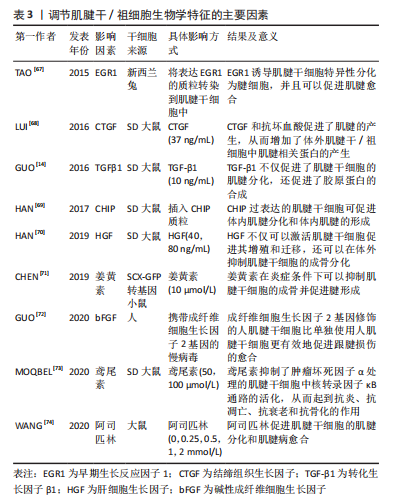

肌腱组织工程的核心是诱导干细胞向肌腱细胞分化,研究者们旨在阐明有利于肌腱干/祖细胞分化的因素。尽管肌腱干/祖细胞有自发分化为肌腱细胞的潜力,但在转化生长因子β1的诱导下,其分化为肌腱系的能力明显增强[14]。除了细胞因子、机械刺激以及低氧张力外,一些药物、基因和蛋白质也能促进肌腱干/祖细胞向肌腱分化。表3是调节肌腱干细胞生物学特征的主要因素的相关研究总结[14,67-74]。一方面,了解促成肌腱干/祖细胞适当分化的因素,可以推进其在肌腱病中的应用。另一方面,它可以为组织工程中的细胞增殖分化提供有利的条件。

2.3.1 细胞因子和生长因子 细胞因子是由各种组织细胞合成和分泌的小分子肽和糖蛋白,它们调节细胞代谢,参与细胞免疫反应和损伤修复[75]。研究表明,一些细胞因子对肌腱干/祖细胞的分化方向有积极的调节作用。同样,某些生长因子也有同样的作用。已被研究的细胞因子包括转化生长因子β1、碱性成纤维细胞生长因子、肝细胞生长因子、结缔组织生长因子和骨形态发生蛋白12,这些都能使肌腱干/祖细胞向肌腱分化[68,72,76-78]。

转化生长因子β1不仅在肌腱愈合中具有重要作用,而且已被证明能使间充质干细胞分化为肌腱细胞。应用转化生长因子β1可以上调间充质干细胞中的Scx和Tnmd [79-80]。肌腱干/祖细胞作为间充质干细胞的一种,转化生长因子β1也是促进肌腱干/祖细胞向腱细胞分化的强大催化剂。在GUO等[14]的研究中,与使肌腱自发分化的组相比,转化生长因子β1组表现出更高的肌腱标志物,包括Ⅰ型胶原蛋白、纤维调节素和Dcn;然而,与自发组相比,转化生长因子β1组的腱调节蛋白明显较低,这可能是由于转化生长因子信号通路调节的因素抑制了腱调节蛋白的表达。除此之外,Scx、Mkx、Egr1和Eya1等肌腱转录因子在转化生长因子 β1诱导组明显上调。同样,还有学者研究了肿瘤坏死因子α和转化生长因子 β1对肌腱干/祖细胞的增殖和分化的影响[81]。他们发现,肿瘤坏死因子α单独使用能明显抑制肌腱干细胞的分化,而结合转化生长因子β1则能增强肌腱干细胞的分化。其中,肌腱干/祖细胞的增殖和分化是由转化生长因子β1通过激活转化生长因子β/BMP信号通路刺激的。

此外,碱性成纤维细胞生长因子是成纤维细胞生长因子家族的一员,具有促进血管生成、细胞增殖和胶原蛋白合成的功能[82-84]。GUO等[72]将携带碱性成纤维细胞生长因子基因的腺病毒转染到人类肌腱干细胞中,然后将FGF-2-h肌腱干细胞移植到大鼠损伤模型中,转染7 d后,与没有碱性成纤维细胞生长因子的对照组相比,碱性成纤维细胞生长因子组有相对较高的Ⅲ型胶原蛋白生成水平和SCXA(调节肌腱干细胞向肌腱细胞的分化)的高表达[72],结果表明,用碱性成纤维细胞生长因子基因修饰的人肌腱干/祖细胞促进并改善了肌腱愈合的质量。

肝细胞生长因子最初发现于肝脏,由间充质干细胞分泌,可促进伤口愈合以及激活干细胞[77,85]。最近的一项调查显示,肝细胞生长因子通过PI3K/AKT或MAPK/ERK1/2信号通路促进肌腱干/祖细胞增殖,肌腱干/祖细胞增殖数量与肝细胞生长因子浓度正相关。同样,肝细胞生长因子诱导HGF/c-Met途径的激活,降低骨形态发生蛋白/Smad1/5/8的活性,从而抑制肌腱干/祖细胞向成骨方向分化[70]。

除此之外,结缔组织生长因子还能促进细胞增殖和分化,它还能使骨髓间质干细胞分化为成纤维细胞,这在人脐带静脉内皮细胞中被发现[86]。此外,结缔组织生长因子还被证明可以抑制肌腱干/祖细胞的衰老,同时促进肌腱干/祖细胞的自我更新和相关肌腱标志物Scx、Tnmd,Nestin和COL1a1的表达。结缔组织生长因子对肌腱干细胞衰老的抑制机制是提高细胞周期蛋白D1/CDK4的水平和减少p27kip1的表达[87]。有研究将经结缔组织生长因子和抗坏血酸处理的肌腱干/祖细胞移植到大鼠髌骨肌腱缺损模型,与对照组相比,结缔组织生长因子组修复的肌腱不仅具有整齐的胶原纤维和增加的细胞分布,而且还降低了该模型异位骨化的风险[68]。同样地,骨形态发生蛋白12也能诱导干细胞向腱细胞分化。XU等[78]应用腺病毒载体同时转染骨形态发生蛋白12和结缔组织生长因子到肌腱干/祖细胞,然后将其移植到大鼠受损的髌骨肌腱。体外实验显示,在骨形态发生蛋白12与结缔组织生长因子转染的肌腱干/祖细胞中,肌腱标记基因,包括ⅠⅢ型和Ⅲ型胶原蛋白、Tenascin-C和scx都被上调;相比之下,非肌腱形成的标志基因都被下调了。体内实验表明,转染的肌腱干/祖细胞明显促进了髌腱的愈合。

2.3.2 适度机械刺激和细胞外基质 机械刺激和细胞外基质的地形对肌腱干/祖细胞的增殖分化至关重要[88]。众所周知,正常的机械刺激是肌腱发育的必要条件,机械刺激也被认为是调控肌腱干/祖细胞分化的关键因素之一[45]。其功能是通过上调机械生长因子的表达来促进肌腱干/祖细胞的增殖和分化[89]。例如,有研究观察到8%的双轴机械负荷增加了肌腱干/祖细胞中基质金属蛋白酶和整合素的表达;此外,纤连蛋白、lumican和versican的表达也有所增加;重要的是,它们的增加不仅能促进胶原纤维的产生,而且还有助于细胞的增殖和细胞外基质的合成[90]。除此之外,研究人员发现三维单轴机械负荷通过激活PI3K/AKT途径诱导肌腱特异性分化(如标志基因SCX,Mohawk及TNMD增加)[91]。

干细胞的生态位对其分化方向至关重要,而由生物材料的地形构成的干细胞生态位可以调节肌腱干/祖细胞的分化。同样,生物材料的刚度、纤维直径和纤维排列也会影响干细胞的分化[88]。首先,基质硬度对肌腱干/祖细胞的分化有调节作用,这主要是通过激活FAK-ERK1/2信号通路。正常肌腱组织的细胞外基质硬度相对较高,肌腱干/祖细胞的增殖速度也会加快。然而,在肌腱病患者中,肌腱组织的基质硬度明显降

低[92]。基质硬度的降低会诱发软骨成骨,进而导致肌腱病[93]。其次,纤维直径和纤维排列对肌腱干/祖细胞的分化也有影响。有研究制备了不同直径和机械性能的丝质纤维素薄膜,并在5,10,15和20 μm的丝素纤维素薄膜中培养了大鼠肌腱干/祖细胞,除了5 μm的丝素纤维素薄膜,10,15和20 μm的丝素纤维素薄膜表现出与正常肌腱相似的极限载荷和最大拉力;他们还评估了丝质纤维素薄膜细胞的形态和生存能力,发现10 μm丝素纤维素薄膜中的肌腱干/祖细胞表现出定向细胞排列和拉长的细胞形态;此外,肌腱干/祖细胞中肌腱相关基因SCX、胶原蛋白Ⅰ和TNMD的表达明显高于其他组,这些数据表明,肌腱干/祖细胞在10 μm的丝素纤维素薄膜上有最佳的生物反应[94]。最后,不同类型的脱细胞基质对人类肌腱干/祖细胞有不同的分化作用。在肌腱衍生的脱细胞基质上的人肌腱干/祖细胞表现出增强的肌腱系分化。肌腱衍生的脱细胞基质通过调节肌腱和骨的特异性转录因子,促进了肌腱的特异性表达,抑制了成骨的分化。

总之,基质细胞外基质组成、地形模式和机械性能共同促进了肌腱干/祖细胞的各种分化方向。选择适当的方法制备合适的具有多孔结构和优异力学性能的肌腱组织工程支架是一个重要的问题。未来的支架应满足以下条件:与天然肌腱结构相似、模仿天然肌腱的力学性能、良好的生物相容性。未来的研究仍然需要进一步研究基质促进干细胞分化的机制。

2.3.3 低氧张力 大多数细胞的最初发育是在缺氧状态下进行的[95]。另外,有研究表明,肌腱愈合需要一个低氧环境,而干细胞在低氧张力下有很高的增殖能力 [96]。低氧可以通过调节缺氧诱导因子1α的表达影响干细胞的分化。此外,缺氧可以增加血管内皮生长因子的表达,作为促进血管生成的一种方式[97]。由于肌腱的低血管性和低细胞密度,肌腱组织周围缺乏营养,受伤后难以愈合,所以血管生成对肌腱愈合尤为重要[98]。

与其他干细胞一样,肌腱干/祖细胞在缺氧条件下表现更好。ZHANG等[99]将人肌腱干/祖细胞暴露在体积分数5%的氧气中,发现不仅肌腱干/祖细胞的数量增加,而且它们的干性标志物的表达也高于常氧条件下;除此之外,肌腱细胞相关的基因,如tenascin-C的表达水平高于常氧,而非肌腱细胞相关的基因,包括sox9及Runx2的表达水平较低。LI等[100]从健康大鼠跟腱中分离出肌腱干/祖细胞,并将其置于体积分数3%的氧气中,与体积分数20%的氧气相比,肌腱干/祖细胞的增殖能力更强,成骨能力下降。

低氧张力不仅改善了正常肌腱干/祖细胞的增殖能力,也改善了老化干细胞的分化能力[101]。肌腱干/祖细胞错误分化的原因之一是氧张力的变化[99]。正常肌腱组织含氧量较少,如果氧张力升高,将导致肌腱干/祖细胞错误分化为非肌腱细胞。因此,缺氧有利于 肌腱干/祖细胞在体外有效扩增,用于肌腱组织工程。

2.3.4 药物 肌腱钙化是一个比较棘手的临床问题,其病因是基于肌腱干/祖细胞在炎症条件下向成骨细胞的分化。姜黄素是一种小分子药物,具有抗炎和抗氧化作用[102-103]。有研究建立了一个大鼠肌腱钙化模型,其中注射了含有姜黄素的壳聚糖微球,结果显示姜黄素通过下调炎症介质如肿瘤坏死因子α、白细胞介素1α和白细胞介素1β来缓解炎症反应,从而抑制肌腱钙化,促进肌腱愈合;同时,姜黄素能促进肌腱干/祖细胞向肌腱分化,促进炎症环境下的胶原蛋白合成[71]。肿瘤坏死因子α可诱发肌腱病,并可引起肌腱干/祖细胞的凋亡和分化为骨细胞[81]。鸢尾花素是一种治疗肌腱病的新药,通过阻断MAPK和核转录因子κB途径来抑制肿瘤坏死因子α的表达。除此之外,鸢尾花素还能逆转肌腱病的钙化,以及增加胶原蛋白Ⅰ的表达[73]。

据报道,阿司匹林是治疗肌腱病的常用药物,最近的调查显示,它不仅能促进肌腱干/祖细胞的肌腱分化,还能抑制肌腱干细胞向脂肪细胞分化[73]。阿司匹林通过生长分化因子7诱导的Smad1/5信号通路的激活促进肌腱干/祖细胞的成腱分化[74]。另外,阿司匹林可以通过下调PTEN/PI3K/AKT信号,抑制肌腱病中肌腱干/祖细胞的脂肪生成分化,从而改善愈合的肌腱的生物力学行为[104]。然而,阿司匹林治疗肌腱病所暴露出的弊端已被证明,因为高浓度的阿司匹林通过线粒体/caspase-3途径促进肌腱干/祖细胞的凋亡,这阻碍了肌腱病的愈合[105]。

2.3.5 基因和蛋白 肌腱的发育和分化需要一些转录因子和特定蛋白的参与,如Scx和Tnmd[106],特别是Fos基因、EGR1转录因子和CHIP蛋白对肌腱干/祖细胞的分化有积极作用[67,69,107]。首先是Fos基因,CHEN等[107]发现Fos基因是成骨分化的潜在分化因子,MKX蛋白、SCX和Tnmd在Fos基因过表达组的肌腱干/祖细胞中明显增加,而Fos敲除组的情况则相反,其次,EGR1已被证明与肌腱分化有关[108]。TAO等[67]将表达EGR1的质粒移植到肌腱干/祖细胞(EGR1-肌腱干/祖细胞)中,发现Scx、Tnmd和Ⅰ型胶原蛋白高度表达,而PPARγ、RUNX2和SOX9的转录水平较低,此结果表明,EGR1上调了成骨分化,抑制了脂肪细胞、成骨细胞和软骨细胞的分化。除此之外,将EGR1-肌腱干/祖细胞植入兔子肩袖损伤模型中,与其他组相比,EGR1-肌腱干/祖细胞的治疗效果最好。最后,CHIP蛋白在破骨细胞调控中具有关键作用,最近研究了它对肌腱干/祖细胞分化的影响。HAN等[69]将表达CHIP的慢病毒导入肌腱干/祖细胞,观察细胞的增殖和分化状况,结果显示CHIP不仅增加了肌腱干/祖细胞的细胞数量,而且还明显增加了肌腱相关基因Scx、Tnmd和Ⅰ型胶原蛋白。

| [1] SCHNEIDER M, DOCHEVA D. Mysteries behind the cellular content of tendon tissues. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2017;25(12):E289-E290. [2] SILBERNAGEL KG, HANLON S, SPRAGUE A. Current clinical concepts: conservative management of achilles tendinopathy. J Athl Train. 2020;55(5):438-447. [3] AICALE R, TARANTINO D, MAFFULLI N. Overuse injuries in sport: a comprehensive overview. J Orthop Surg Res. 2018;13(1):309. [4] RIO E, MOSELEY L, PURDAM C, et al. The pain of tendinopathy: physiological or pathophysiological? Sports Med. 2014;44(1):9-23. [5] CAMPBELL RS, GRAINGER AJ. Current concepts in imaging of tendinopathy. Clin Radiol. 2001;56(4):253-267. [6] ABATE M, SCHIAVONE C, SALINI V, et al. Occurrence of tendon pathologies in metabolic disorders. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2013;52(4):599-608. [7] LI HY, HUA YH. Achilles tendinopathy: current concepts about the basic science and clinical treatments. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:6492597. [8] GOLDIN M, MALANGA GA. Tendinopathy: a review of the pathophysiology and evidence for treatment. Phys Sportsmed. 2013;41(3):36-49. [9] HOPKINS C, FU SC, CHUA E, et al. Critical review on the socio-economic impact of tendinopathy. Asia Pac J Sports Med Arthrosc Rehabil Technol. 2016;4:9-20. [10] CARDOSO TB, PIZZARI T, KINSELLA R, et al. Current trends in tendinopathy management. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2019;33(1):122-140. [11] WEI B, LU J. Characterization of tendon-derived stem cells and rescue tendon injury. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2021;17(5):1534-1551. [12] LEONG DJ, SUN HB. Mesenchymal stem cells in tendon repair and regeneration: basic understanding and translational challenges. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2016;1383(1):88-96. [13] TAN Q, LUI PPY, RUI YF, et al. Comparison of potentials of stem cells isolated from tendon and bone marrow for musculoskeletal tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012;18(7-8):840-851. [14] GUO J, CHAN KM, ZHANG JF, et al. Tendon-derived stem cells undergo spontaneous tenogenic differentiation. Exp Cell Res. 2016;341(1):1-7. [15] BI Y, EHIRCHIOU D, KILTS TM, et al. Identification of tendon stem/progenitor cells and the role of the extracellular matrix in their niche. Nat Med. 2007;13(10):1219-1227. [16] WU YF, CHEN C, TANG JB, et al. Growth and stem cell characteristics of tendon-derived cells with different initial seeding densities: an in vitro study in mouse flexor tendon cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2020;29(15):1016-1025. [17] YIN Z, CHEN X, CHEN JL, et al. The regulation of tendon stem cell differentiation by the alignment of nanofibers. Biomaterials. 2010;31(8):2163-2175. [18] ZHANG X, LIN YC, RUI YF, et al. Therapeutic roles of tendon stem/progenitor cells in tendinopathy. Stem Cells Int. 2016;2016:4076578. [19] GLASS ZA, SCHIELE NR, KUO CK. Informing tendon tissue engineering with embryonic development. J Biomechan. 2014;47(9):1964-1968. [20] CHEN E, YANG L, YE C, et al. An asymmetric chitosan scaffold for tendon tissue engineering: in vitro and in vivo evaluation with rat tendon stem/progenitor cells. Acta Biomaterialia. 2018;73:377-387. [21] LUI PP, CHAN KM. Tendon-derived stem cells (TDSCs): from basic science to potential roles in tendon pathology and tissue engineering applications. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2011;7(4):883-897. [22] ZHANG J, WANG JHC. Mechanobiological response of tendon stem cells: implications of tendon homeostasis and pathogenesis of tendinopathy. J Orthop Res. 2010;28(5):639-643. [23] COOK JL, KHAN KM, PURDAM C. Achilles tendinopathy. Manual Ther. 2002;7(3):121-130. [24] YANG J, ZHAO Q, WANG K, et al. Isolation, culture and biological characteristics of multipotent porcine tendon-derived stem cells. Int J Mol Med. 2018;41(6):3611-3619. [25] RUI YF, LUI PP, LI G, et al. Isolation and characterization of multipotent rat tendon-derived stem cells. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16(5):1549-1558. [26] ZHANG J, WANG JHC. Characterization of differential properties of rabbit tendon stem cells and tenocytes. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:10. [27] LI Y, WU T, LIU S. Identification and distinction of tenocytes and tendon-derived stem cells. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:629515. [28] DOMINICI M, LE BLANC K, MUELLER I, et al. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8(4):315-317. [29] DEAN BJF, FRANKLIN SL, CARR AJ. The peripheral neuronal phenotype is important in the pathogenesis of painful human tendinopathy: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(9):3036-3046. [30] WU F, NERLICH M, DOCHEVA D. Tendon injuries: basic science and new repair proposals. Efort Open Reviews. 2017;2(7):332-342. [31] STEINMANN S, PFEIFER CG, BROCHHAUSEN C, et al. Spectrum of tendon pathologies: triggers, trails and end-state. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(3):844. [32] RUI YF, LUI PP, CHAN LS, et al. Does erroneous differentiation of tendon-derived stem cells contribute to the pathogenesis of calcifying tendinopathy? Chin Med J (Engl). 2011;124(4):606-610. [33] ZHANG J, WANG JH. Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) exerts biphasic effects on human tendon stem cells. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e87706. [34] LIN YC, LI YJ, RUI YF, et al. The effects of high glucose on tendon-derived stem cells: implications of the pathogenesis of diabetic tendon disorders. Oncotarget. 2017;8(11):17518-17528. [35] DENG G, LI K, CHEN S, et al. Interleukin‑10 promotes proliferation and migration, and inhibits tendon differentiation via the JAK/Stat3 pathway in tendon‑derived stem cells in vitro. Mol Med Rep. 2018;18(6):5044-5052. [36] CHEN S, DENG G, LI K, et al. Interleukin-6 promotes proliferation but inhibits tenogenic differentiation via the Janus kinase/signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 (JAK/STAT3) pathway in tendon-derived stem cells. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:1567-1573. [37] LI K, DENG Y, DENG G, et al. High cholesterol induces apoptosis and autophagy through the ROS-activated AKT/FOXO1 pathway in tendon-derived stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;11(1):131. [38] DAI GC, LI YJ, CHEN MH, et al. Tendon stem/progenitor cell ageing: modulation and rejuvenation. World J Stem Cells. 2019;11(9):677-692. [39] WANG H, DAI GC, LI YJ, et al. Targeting senescent tendon stem/progenitor cells to prevent or treat age-related tendon disorders. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2023;19(3):680-693. [40] ZHOU Z, AKINBIYI T, XU L, et al. Tendon-derived stem/progenitor cell aging: defective self-renewal and altered fate. Aging Cell. 2010;9(5):911-915. [41] MUSS HB, SMITHERMAN A, WOOD WA, et al. p16 a biomarker of aging and tolerance for cancer therapy. Transl Cancer Res. 2020;9(9):5732-5742. [42] HAN W, WANG B, LIU J, et al. The p16/miR-217/EGR1 pathway modulates age-related tenogenic differentiation in tendon stem/progenitor cells. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai). 2017;49(11):1015-1021. [43] KIDERLEN S, POLZER C, RÄDLER JO, et al. Age related changes in cell stiffness of tendon stem/progenitor cells and a rejuvenating effect of ROCK-inhibition. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;509(3):839-844. [44] KJAER M. Role of extracellular matrix in adaptation of tendon and skeletal muscle to mechanical loading. Physiol Rev. 2004;84(2):649-698. [45] GALLOWAY MT, LALLEY AL, SHEARN JT. The role of mechanical loading in tendon development, maintenance, injury, and repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(17):1620-1628. [46] NG GY, CHUNG PY, WANG JS, et al. Enforced bipedal downhill running induces Achilles tendinosis in rats. Connect Tissue Res. 2011;52(6):466-471. [47] SOSLOWSKY LJ, THOMOPOULOS S, TUN S, et al. Neer Award 1999. Overuse activity injures the supraspinatus tendon in an animal model: a histologic and biomechanical study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9(2):79-84. [48] GODFRAIND T. Calcium antagonists and vasodilatation. Pharmacol Ther. 1994;64(1): 37-75. [49] NIE D, ZHOU Y, WANG W, et al. Mechanical overloading induced-activation of mtor signaling in tendon stem/progenitor cells contributes to tendinopathy development. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:687856. [50] LIU X, CHEN W, ZHOU Y, et al. Mechanical tension promotes the osteogenic differentiation of rat tendon-derived stem cells through the wnt5a/wnt5b/jnk signaling pathway. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;36(2):517-530. [51] SHI Y, FU Y, TONG W, et al. Uniaxial mechanical tension promoted osteogenic differentiation of rat tendon-derived stem cells (rTDSCs) via the Wnt5a-RhoA pathway. J Cell Biochem. 2012;113(10):3133-3142. [52] CILLI F, KHAN M, FU F, et al. Prostaglandin E2 affects proliferation and collagen synthesis by human patellar tendon fibroblasts. Clin J Sport Med. 2004;14(4):232-236. [53] ZHANG J, WANG JH. Production of PGE(2) increases in tendons subjected to repetitive mechanical loading and induces differentiation of tendon stem cells into non-tenocytes. J Orthop Res. 2010;28(2):198-203. [54] ZHANG K, ASAI S, YU B, et al. IL-1β irreversibly inhibits tenogenic differentiation and alters metabolism in injured tendon-derived progenitor cells in vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;463(4):667-672. [55] COOMBES BK, BISSET L, VICENZINO B. Efficacy and safety of corticosteroid injections and other injections for management of tendinopathy: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2010;376(9754):1751-1767. [56] MCQUILLAN R, GREGAN P. Tendon rupture as a complication of corticosteroid therapy. Palliat Med. 2005;19(4):352-353. [57] ZHANG J, KEENAN C, WANG JH. The effects of dexamethasone on human patellar tendon stem cells: implications for dexamethasone treatment of tendon injury. J Orthop Res. 2013;31(1):105-110. [58] CHEN W, TANG H, ZHOU M, et al. Dexamethasone inhibits the differentiation of rat tendon stem cells into tenocytes by targeting the scleraxis gene. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2015;152:16-24. [59] SMITH WL, URADE Y, JAKOBSSON PJ. Enzymes of the cyclooxygenase pathways of prostanoid biosynthesis. Chem Rev. 2011;111(10):5821-5865. [60] ZHANG K, ZHANG S, LI Q, et al. Effects of celecoxib on proliferation and tenocytic differentiation of tendon-derived stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014; 450(1):762-766. [61] RANGER TA, WONG AM, COOK JL, et al. Is there an association between tendinopathy and diabetes mellitus? A systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2016; 50(16):982-989. [62] BEDI A, FOX AJ, HARRIS PE, et al. Diabetes mellitus impairs tendon-bone healing after rotator cuff repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(7):978-988. [63] DE OLIVEIRA RR, MARTINS CS, ROCHA YR, et al. Experimental diabetes induces structural, inflammatory and vascular changes of Achilles tendons. PLoS One. 2013; 8(10):e74942. [64] BURNER T, GOHR C, MITTON-FITZGERALD E, et al. Hyperglycemia reduces proteoglycan levels in tendons. Connect Tissue Res. 2012;53(6):535-541. [65] SHI L, LI YJ, DAI GC, et al. Impaired function of tendon-derived stem cells in experimental diabetes mellitus rat tendons: implications for cellular mechanism of diabetic tendon disorder. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10(1):27. [66] LI K, DENG G, DENG Y, et al. High cholesterol inhibits tendon-related gene expressions in tendon-derived stem cells through reactive oxygen species-activated nuclear factor-κB signaling. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(10):18017-18028. [67] TAO X, LIU J, CHEN L, et al. EGR1 induces tenogenic differentiation of tendon stem cells and promotes rabbit rotator cuff repair. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;35(2):699-709. [68] LUI PP, WONG OT, LEE YW. Transplantation of tendon-derived stem cells pre-treated with connective tissue growth factor and ascorbic acid in vitro promoted better tendon repair in a patellar tendon window injury rat model. Cytotherapy. 2016;18(1):99-112. [69] HAN W, CHEN L, LIU J, et al. Enhanced tenogenic differentiation and tendon-like tissue formation by CHIP overexpression in tendon-derived stem cells. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai). 2017;49(4):311-317. [70] HAN P, CUI Q, LU W, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor plays a dual role in tendon-derived stem cell proliferation, migration, and differentiation. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(10): 17382-17391. [71] CHEN Y, XIE Y, LIU M, et al. Controlled-release curcumin attenuates progression of tendon ectopic calcification by regulating the differentiation of tendon stem/progenitor cells. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2019;103:109711. [72] GUO D, LI H, LIU Y, et al. Fibroblast growth factor-2 promotes the function of tendon-derived stem cells in Achilles tendon restoration in an Achilles tendon injury rat model. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2020;521(1):91-97. [73] MOQBEL SAA, XU K, CHEN Z, et al. Tectorigenin alleviates inflammation, apoptosis, and ossification in rat tendon-derived stem cells via modulating NF-kappa B and MAPK pathways. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:568894. [74] WANG Y, HE G, TANG H, et al. Aspirin promotes tenogenic differentiation of tendon stem cells and facilitates tendinopathy healing through regulating the GDF7/Smad1/5 signaling pathway. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235(5):4778-4789. [75] MOLLOY T, WANG Y, MURRELL G. The roles of growth factors in tendon and ligament healing. Sports Med. 2003;33(5):381-394. [76] ZHANG L, CHEN S, CHANG P, et al. Harmful effects of leukocyte-rich platelet-rich plasma on rabbit tendon stem cells in vitro. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(8):1941-1951. [77] GAL-LEVI R, LESHEM Y, AOKI S, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor plays a dual role in regulating skeletal muscle satellite cell proliferation and differentiation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1402(1):39-51. [78] XU K, SUN Y, KH AL-ANI M, et al. Synergistic promoting effects of bone morphogenetic protein 12/connective tissue growth factor on functional differentiation of tendon derived stem cells and patellar tendon window defect regeneration. J Biomech. 2018;66:95-102. [79] LORDA-DIEZ CI, MONTERO JA, MARTINEZ-CUE C, et al. Transforming growth factors beta coordinate cartilage and tendon differentiation in the developing limb mesenchyme. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(43):29988-29996. [80] ARIMURA H, SHUKUNAMI C, TOKUNAGA T, et al. TGF-β1 improves biomechanical strength by extracellular matrix accumulation without increasing the number of tenogenic lineage cells in a rat rotator cuff repair model. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(10): 2394-2404. [81] HAN P, CUI Q, YANG S, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-α and transforming growth factor-β1 facilitate differentiation and proliferation of tendon-derived stem cells in vitro. Biotechnol Lett. 2017;39(5):711-719. [82] CHEN M, SONG K, RAO N, et al. Roles of exogenously regulated bFGF expression in angiogenesis and bone regeneration in rat calvarial defects. Int J Mol Med. 2011;27(4): 545-553. [83] CAO R, BRÅKENHIELM E, PAWLIUK R, et al. Angiogenic synergism, vascular stability and improvement of hind-limb ischemia by a combination of PDGF-BB and FGF-2. Nat Med. 2003;9(5):604-613. [84] LU J, JIANG L, CHEN Y, et al. The functions and mechanisms of basic fibroblast growth factor in tendon repair. Front Physiol. 2022;13:852795. [85] LAN YW, THENG SM, HUANG TT, et al. Oncostatin m-preconditioned mesenchymal stem cells alleviate bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis through paracrine effects of the hepatocyte growth factor. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2017;6(3):1006-1017. [86] IGARASHI A, OKOCHI H, BRADHAM DM, et al. Regulation of connective tissue growth factor gene expression in human skin fibroblasts and during wound repair. Mol Biol Cell. 1993;4(6):637-645. [87] RUI YF, CHEN MH, LI YJ, et al. CTGF attenuates tendon-derived stem/progenitor cell aging. Stem Cells International. 2019;2019:6257537. [88] CHEN JL, ZHANG W, LIU ZY, et al. Physical regulation of stem cells differentiation into teno-lineage: current strategies and future direction. Cell Tissue Res. 2015;360(2):195-207. [89] ZHANG J, WANG JH. The effects of mechanical loading on tendons--an in vivo and in vitro model study. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e71740. [90] POPOV C, BURGGRAF M, KREJA L, et al. Mechanical stimulation of human tendon stem/progenitor cells results in upregulation of matrix proteins, integrins and MMPs, and activation of p38 and ERK1/2 kinases. BMC Mol Biol. 2015;16:6. [91] WANG T, THIEN C, WANG C, et al. 3D uniaxial mechanical stimulation induces tenogenic differentiation of tendon-derived stem cells through a PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. FASEB J. 2018;32(9):4804-4814. [92] DIRRICHS T, QUACK V, GATZ M, et al. Shear wave elastography (SWE) for the evaluation of patients with tendinopathies. Acad Radiol. 2016;23(10):1204-1213. [93] LIU C, LUO JW, LIANG T, et al. Matrix stiffness regulates the differentiation of tendon-derived stem cells through FAK-ERK1/2 activation. Exp Cell Res. 2018;373(1-2):62-70. [94] LU K, CHEN X, TANG H, et al. Bionic silk fibroin film induces morphological changes and differentiation of tendon stem/progenitor cells. Appl Bionics Biomech. 2020;2020:8865841. [95] MOHYELDIN A, GARZÓN-MUVDI T, QUIÑONES-HINOJOSA A. Oxygen in stem cell biology: a critical component of the stem cell niche. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7(2):150-161. [96] LEE WY, LUI PP, RUI YF. Hypoxia-mediated efficient expansion of human tendon-derived stem cells in vitro. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012;18(5-6):484-498. [97] GUO X, HUANG D, LI D, et al. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells with hypoxic preconditioning improve tenogenic differentiation. J Orthop Surg Res. 2022;17(1):49. [98] RUSSO V, EL KHATIB M, PRENCIPE G, et al. Scaffold-mediated immunoengineering as innovative strategy for tendon regeneration. Cells. 2022;11:266. [99] ZHANG J, WANG JH. Human tendon stem cells better maintain their stemness in hypoxic culture conditions. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e61424. [100] LI P, XU Y, GAN Y, et al. Role of the ERK1/2 signaling pathway in osteogenesis of rat tendon-derived stem cells in normoxic and hypoxic cultures. Int J Med Sci. 2016;13(8): 629-637. [101] JIANG D, JIANG Z, ZHANG Y, et al. Effect of young extrinsic environment stimulated by hypoxia on the function of aged tendon stem cell. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2014;70(2): 967-973. [102] HAN J, PAN XY, XU Y, et al. Curcumin induces autophagy to protect vascular endothelial cell survival from oxidative stress damage. Autophagy. 2012;8(5):812-825. [103] CHEN JJ, DAI L, ZHAO LX, et al. Intrathecal curcumin attenuates pain hypersensitivity and decreases spinal neuroinflammation in rat model of monoarthritis. Sci Rep. 2015;5: 10278. [104] WANG Y, HE G, WANG F, et al. Aspirin inhibits adipogenesis of tendon stem cells and lipids accumulation in rat injury tendon through regulating PTEN/PI3K/AKT signalling.J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23(11):7535-7544. [105] WANG Y, TANG H, HE G, et al. High Concentration of aspirin induces apoptosis in rat tendon stem cells via inhibition of the wnt/β-catenin pathway. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;50(6):2046-2059. [106] HE P, RUAN D, HUANG Z, et al. Comparison of Tendon Development Versus Tendon Healing and Regeneration. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022;10:821667. [107] CHEN J, ZHANG E, ZHANG W, et al. Fos promotes early stage teno-lineage differentiation of tendon stem/progenitor cells in tendon. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2017;6(11):2009-2019. [108] LEJARD V, BLAIS F, GUERQUIN MJ, et al. EGR1 and EGR2 involvement in vertebrate tendon differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(7):5855-5867. [109] WANG JH, KOMATSU I. Tendon stem cells: mechanobiology and development of tendinopathy. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016;920:53-62. |

| [1] | 余伟杰, 刘爱峰, 陈继鑫, 郭天赐, 贾易臻, 冯汇川, 杨家麟. 机器学习在腰椎间盘突出症诊治中的优势和应用策略[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2024, 28(9): 1426-1435. |

| [2] | 杨玉芳, 杨芷姗, 段棉棉, 刘毅恒, 唐正龙, 王 宇. 促红细胞生成素在骨组织工程中的应用及前景[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2024, 28(9): 1443-1449. |

| [3] | 陈凯佳, 刘景云, 曹 宁, 孙建波, 周 燕, 梅建国, 任 强. 组织工程技术在股骨头坏死治疗中的应用及前景[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2024, 28(9): 1450-1456. |

| [4] | 白 晨, 杨文骞, 孟志超, 王宇泽. 损伤前交叉韧带修复及促进移植物愈合的策略[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2024, 28(9): 1457-1463. |

| [5] | 林泽玉, 徐 林. 痛风致骨破坏机制的研究与进展[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2024, 28(8): 1295-1300. |

| [6] | 童奕博 , 李明辉. 骨质疏松性椎体骨折患者椎体成形后邻近椎体再发骨折的影响因素[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2024, 28(8): 1241-1246. |

| [7] | 王姗姗, 舒 晴, 田 峻. 物理因子促进干细胞的成骨分化[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2024, 28(7): 1083-1090. |

| [8] | 潘小龙, 樊飞燕, 应春苗, 刘飞祥, 张运克. 中药抑制间充质干细胞衰老的作用及机制[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2024, 28(7): 1091-1098. |

| [9] | 徐灿丽, 何文星, 汪 磊, 吴芳婷, 王佳慧, 段雪琳, 赵铁建, 赵 斌, 郑 洋. 肝脏类器官研究的文献计量学分析[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2024, 28(7): 1099-1104. |

| [10] | 刘瀚峰, 王晶晶, 余云生. 人造外泌体治疗心肌梗死:应用现状及前景[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2024, 28(7): 1118-1123. |

| [11] | 马树微, 何 生, 韩 冰, 张缭云. 间充质干细胞来源外泌体治疗动物急性肝衰竭的Meta分析[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2024, 28(7): 1137-1142. |

| [12] | 孙宇康, 宋丽娟, 温春丽, 丁智斌, 田 昊, 马 东, 马存根, 翟晓艳. 基于Web of Science近十年干细胞治疗心肌梗死的可视化分析[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2024, 28(7): 1143-1148. |

| [13] | 冯睿钦, 韩 娜, 张 蒙, 谷馨怡, 张丰识. 1%富血小板血浆联合骨髓间充质干细胞促进周围神经损伤的修复[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2024, 28(7): 985-992. |

| [14] | 王 雯, 郑芃芃, 孟浩浩, 刘 浩, 袁长永. 过表达Sema3A促进牙髓干细胞和MC3T3-E1的成骨分化[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2024, 28(7): 993-999. |

| [15] | 邱晓燕, 李碧欣, 黎敬弟, 范垂钦, 马 廉, 王鸿武. MAFA-PDX1过表达慢病毒感染人脐带间充质干细胞向胰岛素分泌细胞的分化[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2024, 28(7): 1000-1006. |

肌腱病的治疗可分为保守治疗和手术治疗,保守治疗包括非类固醇抗炎药、类固醇注射、离心运动和富血小板血浆注射等疗法,当常规药物治疗失败或肌腱断裂时,则采用手术治疗[10],但是这些方法效果并不理想,而且很难将肌腱恢复到受伤前的状态[11]。近年来,干细胞疗法受到广泛关注[12]。肌腱干/祖细胞(tendon stem/progenitor cells,TSPCs)具有自发分化为腱细胞的潜力。此外,肌腱干/祖细胞具有更高的增殖能力和更强的分化潜力[13]。因此,与骨髓间充质干细胞和脂肪来源的干细胞相比,肌腱干/祖细胞在肌腱再生方面具有优势[14-16]。

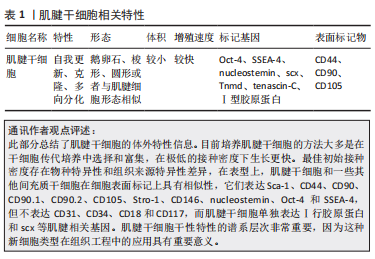

肌腱干/祖细胞是最近在人类和大鼠肌腱中发现的一种独特的细胞群,主要位于由双糖链蛋白聚糖和纤维调节素组成的细胞外基质中。肌腱干/祖细胞与其他干细胞一样,具有自我更新和多向分化的潜力[17]。与其他干细胞不同的是,肌腱干/祖细胞表达较高水平的肌腱相关基因,如巩膜(scleraxis,Scx)、腱调节蛋白(tenomodulin,Tnmd)。此外,由于具有多向分化的潜力,肌腱干/祖细胞生物学特征受到许多因素的改变,不同的外部条件作用于肌腱干/祖细胞可以导致其向不同方向分化。调节肌腱干/祖细胞命运的具体因素并不明显。然而,促进肌腱干/祖细胞向腱细胞分化的可能有利因素包括:生物活性因子(一些生长因子和细胞因子)、适度的机械刺激和细胞外基质的地形、低氧张力、药物(姜黄素等)、基因和蛋白(如Fos等)[18],这为肌腱干/祖细胞在肌腱组织工程中的应用提供了一个新的视角。组织工程学是利用支架、生长因子和种子细胞生成健康的组织来替换受损组织的一种手段,它在治疗多种损伤和疾病中具有巨大的潜力[19]。而肌腱组织工程的核心则是诱导干细胞分化为肌腱组织,较为理想的支架是与天然肌腱细胞外基质的结构和功能相似的[20]。虽然肌腱干/祖细胞在受伤后的组织修复中发挥了重要作用,但当肌腱中的干细胞更新和分化变得不正常时,就会发生肌腱病[21]。例如,肌腱病的病理变化包括软骨细胞、成骨细胞和脂肪细胞数量的增加[22],这表明肌腱愈合的失败是由于肌腱干/祖细胞不正确地分化为软骨细胞、骨细胞和脂肪细胞,进而导致肌腱病[23]。衰老、细胞外基质成分的变化、过度的机械刺激、某些细胞因子和一些系统性疾病可能对调控肌腱干/祖细胞的错误分化有重要意义。

此综述与其他关于肌腱干细胞的综述相比有以下区别及创新性:首先,介绍了肌腱干/祖细胞的相关特性,这有利于肌腱干/祖细胞的识别及追踪;其次,着重全面分析影响其正确以及错误分化的因素,并做出总结,从多个层面了解调节肌腱干/祖细胞错误分化的因素,试图更加深入了解肌腱病的发病机制,为后来的研究者提供理论基础;同时,总结使肌腱干细胞分化为肌腱细胞的因素,为肌腱干细胞在组织工程中的应用奠定了良好的基础,最后,文章还详细阐述了各个影响因素调控肌腱干/祖细胞的具体机制,同时,针对肌腱干/祖细胞错误分化而导致的肌腱病也提出了相应的治疗手段。 中国组织工程研究杂志出版内容重点:干细胞;骨髓干细胞;造血干细胞;脂肪干细胞;肿瘤干细胞;胚胎干细胞;脐带脐血干细胞;干细胞诱导;干细胞分化;组织工程

1.1.1 检索人及检索时间 第一作者在2022 年11月至2023年2月进行检索。

1.1.2 检索文献时限 2007 年10 月至2023 年2 月。

1.1.3 检索数据库 PubMed 和Web of Science数据库。

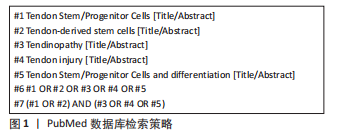

1.1.4 检索词 英文检索词为“Tendon Stem/Progenitor Cells,Tendon-derived stem cells ,Tendinopathy,Tendon injury,differentiation”。

1.1.5 检索文献类型 综述及研究原著。

1.1.6 检索策略 以PubMed 数据库检索策略为例,见图1。

1.2 入组标准

1.2.1 纳入标准 肌腱干细胞分化与肌腱病或肌腱损伤相关的文献。

1.2.2 排除标准 与研究目的不相关的文献或重复性文献。

1.3 文献质量评价和数据的提取 首先通过阅读标题和摘要排除不符合纳入标准的文章,并结合文献追溯法查找遗漏文献,经阅读全文后对保留的文献进行深入研究,最终确定PubMed 数据库文献58篇,Web of Science数据库文献51篇,共109篇英文文献进行总结归纳分析,见图2。

3.2 作者综述区别于他人他篇的特点 肌腱干/祖细胞在肌腱生理和慢性肌腱损伤(肌腱病)中都有重要作用,它在肌腱修复中的应用前景广阔[109]。此综述与其他关于肌腱干细胞的综述相比,着重分析影响其分化的因素,并做出总结。详细阐述了诱导肌腱干细胞向软骨细胞、骨细胞和脂肪细胞分化的影响机制,试图更加深入了解肌腱病的发病机制,为后来的研究者提供理论基础。同时也总结了使肌腱干细胞分化为肌腱细胞的因素,生化以及适当的机械刺激都可以使内源性肌腱干细胞激活,这为肌腱干细胞在组织工程中的应用奠定了良好的基础。

3.3 综述的局限性 首先,虽然肌腱干细胞在肌腱修复中至关重要,但是不同物种以及不同部位的肌腱干细胞具有差异性,文章并未将它们详细区分。其次,肌腱干细胞有不同的亚群,所以还没有准确的生物标志物来追踪肌腱干/祖细胞的谱系。一个更好的方法是使用基因谱系追踪技术来标记肌腱干/祖细胞并追踪肌腱干细胞。最后,用于肌腱病的肌腱干/祖细胞还没有在临床上使用,其安全性需要考察,并进行更多的研究来验证。

3.4 综述的重要意义 文章以调控肌腱干细胞分化为主线,分析了生物化学、生物力学及生物材料等因素对肌腱干细胞分化的影响。肌腱干细胞是组织工程的种子细胞,其在肌腱损伤中具有较好的应用前景。但是它的多向分化像一把双刃剑,有利亦有弊。研究影响肌腱干细胞分化的因素将提供有关肌腱生理学和病理学的重要信息。分析导致其错误分化的因素可以帮助研究者们了解肌腱病的发病机制。相反,诱导其正确分化的因素可以促进肌腱干细胞在体外的扩增和在组织工程中的应用,同时为未来的研究者提供理论基础。 中国组织工程研究杂志出版内容重点:干细胞;骨髓干细胞;造血干细胞;脂肪干细胞;肿瘤干细胞;胚胎干细胞;脐带脐血干细胞;干细胞诱导;干细胞分化;组织工程

#br#

#br#

文题释义:

肌腱干细胞:是具有自我更新、克隆和多向分化潜能的独特细胞群,位于主要由细胞外基质组成的生态龛中。肌腱干细胞的正向分化有助于组织工程的应用。肌腱病:是一种肌肉骨骼疾病,以疼痛和活动能力下降为特征,伴有胶原蛋白紊乱和血管增生的病理变化。

中国组织工程研究杂志出版内容重点:干细胞;骨髓干细胞;造血干细胞;脂肪干细胞;肿瘤干细胞;胚胎干细胞;脐带脐血干细胞;干细胞诱导;干细胞分化;组织工程

肌腱在关节稳定中起着至关重要的作用,它主要由胶原纤维和肌腱驻留细胞组成。肌腱病是骨科中较为棘手的问题之一,约占肌肉骨骼系统疾病的30%-40%。肌腱病的典型症状为疼痛和功能障碍,它的主要病理变化是胶原纤维紊乱和血管增加。肌腱病的病因很复杂,大致可分为内在因素和外在因素。内在因素包括年龄、遗传、系统性疾病、糖尿病、生物力学等。外在因素包括物理负荷、环境、职业等。由于肌腱病发病率高但治愈率低,它不仅损害了个人的生活质量,也增加了社会的经济负担。

中国组织工程研究杂志出版内容重点:干细胞;骨髓干细胞;造血干细胞;脂肪干细胞;肿瘤干细胞;胚胎干细胞;脐带脐血干细胞;干细胞诱导;干细胞分化;组织工程

| 阅读次数 | ||||||

|

全文 |

|

|||||

|

摘要 |

|

|||||