| [1] Hamdan TA. Missile injuries of the limbs: an Iraqi perspective. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14(10 Spec No.):S32-36.[2] Eke PI, Genco RJ. CDC Periodontal Disease Surveillance Project: background, objectives, and progress report. J Periodontol. 2007;78(7 Suppl):1366-1371.[3] Olender E, Brubaker S, Uhrynowska-Tyszkiewicz I, et al. Autologous osteoblast transplantation, an innovative method of bone defect treatment: role of a tissue and cell bank in the process. Transplant Proc. 2014;46(8):2867-2872.[4] Faldini C, Traina F, Perna F, et al. Surgical treatment of aseptic forearm nonunion with plate and opposite bone graft strut. Autograft or allograft? Int Orthop. 2015;39(7):1343-1349. [5] Wang F, Zhang YC, Zhou H, et al. Evaluation of in vitro and in vivo osteogenic differentiation of nano-hydroxyapatite/ chitosan/poly(lactide-co-glycolide) scaffolds with human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2014;102(3):760-768.[6] Matsumoto T, Cooper GM, Gharaibeh B, et al. Cartilage repair in a rat model of osteoarthritis through intraarticular transplantation of muscle-derived stem cells expressing bone morphogenetic protein 4 and soluble Flt-1. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(5):1390-1405.[7] Wang Y, Wang Y, Rui Y, et al. In vitro study on multiple differentiation potential of swine synovium-derived MSCs. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2009 ;23(6): 737-741. [8] Neumann K, Dehne T, Endres M, et al. Chondrogenic differentiation capacity of human mesenchymal progenitor cells derived from subchondral cortico-spongious bone. J Orthop Res. 2008;26(11):1449-1456.[9] Tuli R, Tuli S, Nandi S, et al. Characterization of multipotential mesenchymal progenitor cells derived from human trabecular bone. Stem Cells. 2003;21(6):681-693.[10] Wong HL, Siu WS, Fung CH, et al. Characteristics of stem cells derived from rat fascia: in vitro proliferative and multilineage potential assessment. Mol Med Rep. 2015;11(3):1982-1990.[11] Li G, Peng H, Corsi K, et al. Differential effect of BMP4 on NIH/3T3 and C2C12 cells: implications for endochondral bone formation. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20(9):1611-1623.[12] Foster LJ, Zeemann PA, Li C, et al. Differential expression profiling of membrane proteins by quantitative proteomics in a human mesenchymal stem cell line undergoing osteoblast differentiation. Stem Cells. 2005;23(9):1367-1377.[13] Torrente Y, Tremblay JP, Pisati F, et al. Intraarterial injection of muscle-derived CD34(+)Sca-1(+) stem cells restores dystrophin in mdx mice. J Cell Biol. 2001;152(2):335-348.[14] Williams JT, Southerland SS, Souza J, et al. Cells isolated from adult human skeletal muscle capable of differentiating into multiple mesodermal phenotypes. Am Surg. 1999;65(1): 22-26.[15] Mariani E, Facchini A. Clinical applications and biosafety of human adult mesenchymal stem cells. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18(13):1821-1845.[16] Sherwood RI, Christensen JL, Conboy IM, et al. Isolation of adult mouse myogenic progenitors: functional heterogeneity of cells within and engrafting skeletal muscle. Cell. 2004; 119(4):543-554.[17] Lee JY, Qu-Petersen Z, Cao B, et al. Clonal isolation of muscle-derived cells capable of enhancing muscle regeneration and bone healing. J Cell Biol. 2000;150(5): 1085-1100.[18] Markaryan A, Nelson EG, Kohut RI, et al. Dual immunofluorescence staining of proteoglycans in human temporal bones. Laryngoscope. 2011;121(7):1525-1531.[19] Smith AA. Repeated immunostaining of the same tissue section using alkaline phosphatase as a reporter. Biotech Histochem. 2016;91(6):396-400. [20] Tu Z, Zhang J, Yang G, et al. Characterization of alkaline phosphatase labeled UidA(Gus) probe and its application in testing of transgenic tritordeum. Mol Biol Rep. 2011;38(6): 3629-3634.[21] Verma M, Murkonda BS, Asakura Y, et al. Skeletal Muscle Tissue Clearing for LacZ and Fluorescent Reporters, and Immunofluorescence Staining. Methods Mol Biol. 2016; 1460:129-140. [22] Pati S, Jain S, Behera M, et al. X-gal staining of canine skin tissues: A technique with multiple possible applications. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2014;5(2):245-249.[23] Burn SF. Detection of β-galactosidase activity: X-gal staining. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;886:241-250.[24] Li G, Zheng B, Meszaros LB, et al. Identification and characterization of chondrogenic progenitor cells in the fascia of postnatal skeletal muscle. J Mol Cell Biol. 2011;3(6): 369-377.[25] Qu-Petersen Z, Deasy B, Jankowski R, et al. Identification of a novel population of muscle stem cells in mice: potential for muscle regeneration. J Cell Biol. 2002;157(5):851-864.[26] Couffinhal T, Kearney M, Sullivan A, et al. Histochemical staining following LacZ gene transfer underestimates transfection efficiency. Hum Gene Ther. 1997;8(8):929-934.[27] Lee JY, Peng H, Usas A, et al. Enhancement of bone healing based on ex vivo gene therapy using human muscle-derived cells expressing bone morphogenetic protein 2. Hum Gene Ther. 2002;13(10):1201-1211.[28] Musgrave DS, Pruchnic R, Bosch P, et al. Human skeletal muscle cells in ex vivo gene therapy to deliver bone morphogenetic protein-2. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84(1): 120-127.[29] Bosch P, Musgrave DS, Lee JY, et al. Osteoprogenitor cells within skeletal muscle. J Orthop Res. 2000;18(6):933-944.[30] Kim SJ, Chung YG, Lee YK, et al. Comparison of the osteogenic potentials of autologous cultured osteoblasts and mesenchymal stem cells loaded onto allogeneic cancellous bone granules. Cell Tissue Res. 2012;347(2):303-310.[31] Kang SH, Chung YG, Oh IH, et al. Bone regeneration potential of allogeneic or autogeneic mesenchymal stem cells loaded onto cancellous bone granules in a rabbit radial defect model. Cell Tissue Res. 2014 ;355(1):81-88. [32] Lee SU, Chung YG, Kim SJ, et al. Does size difference in allogeneic cancellous bone granules loaded with differentiated autologous cultured osteoblasts affect osteogenic potential? Cell Tissue Res. 2014;355(2):337-344.[33] Yin Z, Zhang L, Wang J. Repair of articular cartilage defects with "two-phase" tissue engineered cartilage constructed by autologous marrow mesenchymal stem cells and "two-phase" allogeneic bone matrix gelatin. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2005;19(8):652-657.[34] Liu GP, Li YL, Sun J, et al. Repair of calvarial defects with human umbilical cord blood derived mesenchymal stem cells and demineralized bone matrix in athymic rats. Zhonghua Zheng Xing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2010;26(1):34-38.[35] Wan C, He Q, Li G. Allogenic peripheral blood derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) enhance bone regeneration in rabbit ulna critical-sized bone defect model. J Orthop Res. 2006;24(4):610-618.[36] Liu G, Li Y, Sun J, Zhou H, et al. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of osteogenesis of human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells on partially demineralized bone matrix. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16(3):971-982. [37] Yang X, Shi W, Du Y, et al. Experimental study of repairing bone defect with tissue engineered bone seeded with autologous red bone marrow and wrapped by pedicled fascial flap. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2009; 23(10): 1254-1259. [38] Yew TL, Huang TF, Ma HL, et al. Scale-up of MSC under hypoxic conditions for allogeneic transplantation and enhancing bony regeneration in a rabbit calvarial defect model. J Orthop Res. 2012;30(8):1213-1220. [39] Kasten P, Vogel J, Luginbühl R, et al. Influence of platelet-rich plasma on osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells and ectopic bone formation in calcium phosphate ceramics. Cells Tissues Organs. 2006;183(2):68-79. [40] Liu X, Cao L, Jiang Y, et al. Repair of radial segmental bone defects by combined angiopoietin 1 gene transfected bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and platelet-rich plasma tissue engineered bone in rabbits. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2011;25(9):1115-1119. |

.jpg)

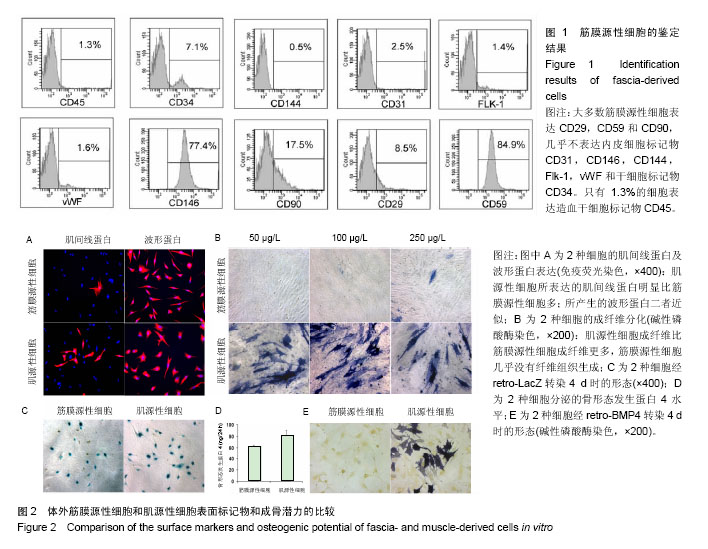

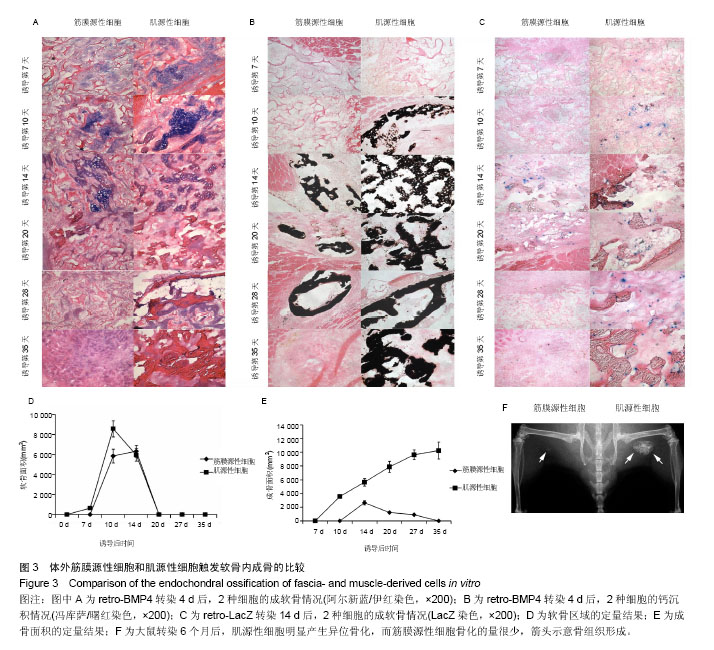

.jpg)