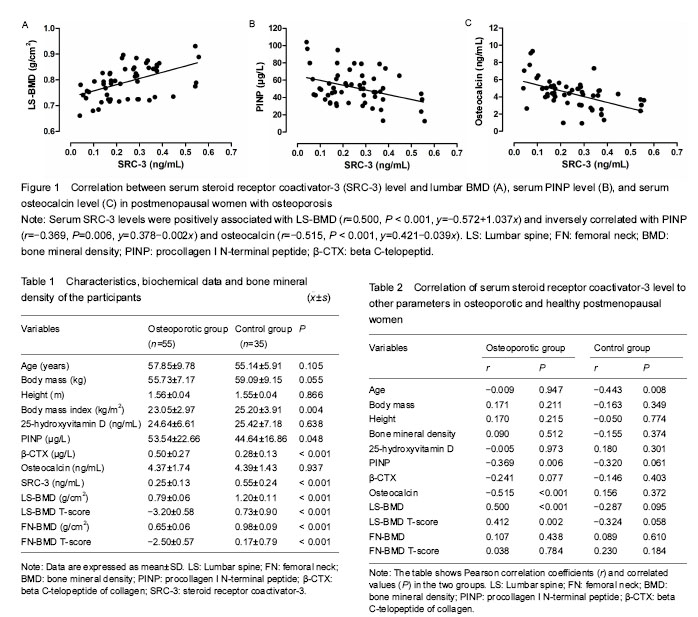

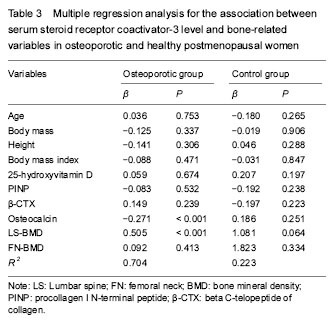

| [1] Han G, Xie S, Fang H, et al. The AIB1 gene polyglutamine repeat length polymorphism contributes to risk of epithelial ovarian cancer risk: a case-control study. Tumour Biol. 2015;36(1):371-374. [2] Zou Z, Luo X, Nie P, et al. Inhibition of SRC-3 enhances sensitivity of human cancer cells to histone deacetylase inhibitors. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;478(1): 227-233. [3] O'Hara J, Vareslija D, McBryan J, et al. AIB1:ERα transcriptional activity is selectively enhanced in aromatase inhibitor-resistant breast cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(12):3305-3315. [4] Song X, Zhang C, Zhao M, et al. Steroid receptor coactivator-3 (src-3/aib1) as a novel therapeutic target in triple negative breast cancer and its inhibition with a phospho-bufalin prodrug. PLoS One. 2015;10(10): e0140011.[5] Sapir-Koren R, Livshits G2. Postmenopausal osteoporosis in rheumatoid arthritis: The estrogen deficiency-immune mechanisms link. Bone. 2017;103:102-115.[6] Seals DR, Jablonski KL, Donato AJ. Aging and vascular endothelial function in humans. Clin Sci (Lond). 2011; 120(9): 357-375. [7] Ikeda K, Tsukui T, Horie-Inoue K, et al. Conditional expression of constitutively active estrogen receptor α in osteoblasts increases bone mineral density in mice. FEBS Lett. 2011;585(9):1303-1309. [8] Kurt O, Yilmaz-Aydogan H, Uyar M, et al. Evaluation of ERα and VDR gene polymorphisms in relation to bone mineral density in Turkish postmenopausal women. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39(6):6723-6730.[9] Wang Y, Li LZ, Zhang YL, et al. LC, a novel estrone-rhein hybrid compound, promotes proliferation and differentiation and protects against cell death in human osteoblastic MG-63 cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;344(1-2):59-68.[10] Sheu YT, Zmuda JM, Cauley JA, et al. Nuclear receptor coactivator-3 alleles are associated with serum bioavailable testosterone, insulin-like growth factor-1, and vertebral bone mass in men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(1): 307-312.[11] Ma Z, Yang Y, Lin J, et al. BFH-OST, a new predictive screening tool for identifying osteoporosis in postmenopausal Han Chinese women. Clin Interv Aging. 2016;11:1051-1059. [12] Xu J, Li Q. Review of the in vivo functions of the p160 steroid receptor coactivator family. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17(9):1681-1692. [13] Karmakar S, Foster EA, Smith CL. Unique roles of p160 coactivators for regulation of breast cancer cell proliferation and estrogen receptor-alpha transcriptional activity. Endocrinology. 2009;150(4):1588-1596. [14] Xu J, Wu RC, O'Malley BW. Normal and cancer-related functions of the p160 steroid receptor co-activator (SRC) family. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9(9):615-630.[15] Labhart P, Karmakar S, Salicru EM, et al. Identification of target genes in breast cancer cells directly regulated by the SRC-3/AIB1 coactivator. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(5):1339-1344.[16] Mödder UI, Sanyal A, Xu J, et al. The skeletal response to estrogen is impaired in female but not in male steroid receptor coactivator (SRC)-1 knock out mice. Bone. 2008;42(2):414-421.[17] Mödder UI, Sanyal A, Xu J, et al. The skeletal response to estrogen is impaired in female but not in male steroid receptor coactivator (SRC)-1 knock out mice. Bone. 2008;42(2):414-421. [18] Yamada T, Kawano H, Sekine K, et al. SRC-1 is necessary for skeletal responses to sex hormones in both males and females. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19(9):1452-1461.[19] Mödder UI, Sanyal A, Xu J, et al. The skeletal response to estrogen is impaired in female but not in male steroid receptor coactivator (SRC)-1 knock out mice. Bone. 2008;42(2):414-421. [20] Mödder UI, Monroe DG, Fraser DG, et al. Skeletal consequences of deletion of steroid receptor coactivator-2/transcription intermediary factor-2. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(28):18767-18777. [21] Jeong JW, Lee KY, Han SJ, et al. The p160 steroid receptor coactivator 2, SRC-2, regulates murine endometrial function and regulates progesterone-independent and -dependent gene expression. Endocrinology. 2007;148(9): 4238-4250. [22] Patel MS, Cole DE, Smith JD, et al. Alleles of the estrogen receptor alpha-gene and an estrogen receptor cotranscriptional activator gene, amplified in breast cancer-1 (AIB1), are associated with quantitative calcaneal ultrasound. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15(11):2231-2239.[23] Méndez JP, Rojano-Mejía D, Pedraza J, et al. Bone mineral density in postmenopausal Mexican-Mestizo women with normal body mass index, overweight, or obesity. Menopause. 2013;20(5):568-572. [24] Palermo A, Tuccinardi D, Defeudis G, et al. BMI and BMD: The Potential Interplay between Obesity and Bone Fragility. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(6). pii: E544. [25] Sritara C, Thakkinstian A, Ongphiphadhanakul B, et al. Causal relationship between the AHSG gene and BMD through fetuin-A and BMI: multiple mediation analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25(5):1555-1562. [26] Fromm-Dornieden C, Pepperl J, Herrmann B, et al. Multiplex analysis of genetic markers related to body mass index (BMI) and bone mineral density (BMD). Anthropol Anz. 2012;69(4):423-438. [27] Badurski J, Jeziernicka E, Dobreńko A, et al. The characteristics of osteoporotic fractures in the region of Bialystok (BOS-2). The application of the WHO algorithm, FRAX®BMI and FRAX®BMD assessment tools to determine patients for intervention. Endokrynol Pol. 2011;62(4):290-298. [28] Afghani A, Barrett-Connor E, Wooten WJ. Resting energy expenditure: a better marker than BMI for BMD in African-American women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37(7):1203-1210.[29] Do?an A, Nakipo?lu-Yüzer GF, Y?ld?zgören MT, et al. Is age or the body mass index (BMI) more determinant of the bone mineral density (BMD) in geriatric women and men? Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010;51(3):338-341.[30] Vs K, K P, Ramesh M, et al. The association of serum osteocalcin with the bone mineral density in post menopausal women. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7(5):814-816. |

.jpg) 文题释义:

激素受体共激活因子:是一类可以辅助多种转录因子并在转录水平上调节多种基因的表达的辅激活因子,在不同的组织细胞中表现出一定的特异性及复杂性,主要包括激素受体共激活因子1、激素受体共激活因子2和激素受体共激活因子3。

激素受体共激活因子3:是类固醇激素核受体超家族成员,它通过与核受体和其它转录因子相互作用来调控转录激活功能,在维护老年人椎体骨量方面可能发挥一定的作用。骨转换标志物包括两类:去除旧骨(吸收)和产生新骨(形成)。Ⅰ型原胶原N-端前肽和β-胶原特殊序列分别是代表骨形成和骨吸收的标记物,在临床上可用于评价骨代谢的状态。

文题释义:

激素受体共激活因子:是一类可以辅助多种转录因子并在转录水平上调节多种基因的表达的辅激活因子,在不同的组织细胞中表现出一定的特异性及复杂性,主要包括激素受体共激活因子1、激素受体共激活因子2和激素受体共激活因子3。

激素受体共激活因子3:是类固醇激素核受体超家族成员,它通过与核受体和其它转录因子相互作用来调控转录激活功能,在维护老年人椎体骨量方面可能发挥一定的作用。骨转换标志物包括两类:去除旧骨(吸收)和产生新骨(形成)。Ⅰ型原胶原N-端前肽和β-胶原特殊序列分别是代表骨形成和骨吸收的标记物,在临床上可用于评价骨代谢的状态。.jpg) 文题释义:

激素受体共激活因子:是一类可以辅助多种转录因子并在转录水平上调节多种基因的表达的辅激活因子,在不同的组织细胞中表现出一定的特异性及复杂性,主要包括激素受体共激活因子1、激素受体共激活因子2和激素受体共激活因子3。

激素受体共激活因子3:是类固醇激素核受体超家族成员,它通过与核受体和其它转录因子相互作用来调控转录激活功能,在维护老年人椎体骨量方面可能发挥一定的作用。骨转换标志物包括两类:去除旧骨(吸收)和产生新骨(形成)。Ⅰ型原胶原N-端前肽和β-胶原特殊序列分别是代表骨形成和骨吸收的标记物,在临床上可用于评价骨代谢的状态。

文题释义:

激素受体共激活因子:是一类可以辅助多种转录因子并在转录水平上调节多种基因的表达的辅激活因子,在不同的组织细胞中表现出一定的特异性及复杂性,主要包括激素受体共激活因子1、激素受体共激活因子2和激素受体共激活因子3。

激素受体共激活因子3:是类固醇激素核受体超家族成员,它通过与核受体和其它转录因子相互作用来调控转录激活功能,在维护老年人椎体骨量方面可能发挥一定的作用。骨转换标志物包括两类:去除旧骨(吸收)和产生新骨(形成)。Ⅰ型原胶原N-端前肽和β-胶原特殊序列分别是代表骨形成和骨吸收的标记物,在临床上可用于评价骨代谢的状态。

.jpg) 文题释义:

激素受体共激活因子:是一类可以辅助多种转录因子并在转录水平上调节多种基因的表达的辅激活因子,在不同的组织细胞中表现出一定的特异性及复杂性,主要包括激素受体共激活因子1、激素受体共激活因子2和激素受体共激活因子3。

激素受体共激活因子3:是类固醇激素核受体超家族成员,它通过与核受体和其它转录因子相互作用来调控转录激活功能,在维护老年人椎体骨量方面可能发挥一定的作用。骨转换标志物包括两类:去除旧骨(吸收)和产生新骨(形成)。Ⅰ型原胶原N-端前肽和β-胶原特殊序列分别是代表骨形成和骨吸收的标记物,在临床上可用于评价骨代谢的状态。

文题释义:

激素受体共激活因子:是一类可以辅助多种转录因子并在转录水平上调节多种基因的表达的辅激活因子,在不同的组织细胞中表现出一定的特异性及复杂性,主要包括激素受体共激活因子1、激素受体共激活因子2和激素受体共激活因子3。

激素受体共激活因子3:是类固醇激素核受体超家族成员,它通过与核受体和其它转录因子相互作用来调控转录激活功能,在维护老年人椎体骨量方面可能发挥一定的作用。骨转换标志物包括两类:去除旧骨(吸收)和产生新骨(形成)。Ⅰ型原胶原N-端前肽和β-胶原特殊序列分别是代表骨形成和骨吸收的标记物,在临床上可用于评价骨代谢的状态。