• 干细胞培养与分化 stem cell culture and differentiation • 上一篇 下一篇

人胚胎纹状体来源神经干细胞的体外培养

樊明超1,王巧玲2,刘 克1,张 欣1,关云谦3,孙 鹏4

- 1青岛大学医学院附属医院神经外科ICU,山东省青岛市 266003;2青岛市市北区镇江路街道社区卫生服务中心,山东省青岛市 266033;3首都医科大学宣武医院细胞治疗中心,北京市 100053;4青岛大学医学院附属医院神经外科,山东省青岛市 266003

-

收稿日期:2012-09-19修回日期:2012-11-07出版日期:2013-07-02发布日期:2013-07-02 -

通讯作者:孙鹏,博士,教授,博士生导师。青岛大学医学院附属医院神经外科,山东省青岛市 266003 -

作者简介:樊明超★,男,1982年生,山东省嘉祥县人,汉族,硕士,主治医师,主要从事颅脑外伤及神经干细胞移植的研究。 王巧玲,女,1979年生,山东省巨野县人,汉族,医师。 -

基金资助:山东省自然科学基金项目(z2008c06);国家自然科学基金项目(81171208)。

In vitro culture of human embryonic striatum-derived neural stem cells

Fan Ming-chao1, Wang Qiao-ling2, Liu Ke1, Zhang Xin1, Guan Yun-qian3, Sun Peng4

- 1 Department of Neurosurgical Intensive Care Unit, the Affiliated Hospital of Medical College, Qingdao University, Qingdao 266003, Shandong Province, China

2 Community Medical Service Center of Zhenjiang Road, Qingdao 266033, Shandong Province, China

3 Cell Therapy Center, Xuanwu Hospital Capital Medical University, Beijing 100053, China

4 Department of Neurosurgery, the Affiliated Hospital of Medical College, Qingdao University, Qingdao 266003, Shandong Province, China

-

Received:2012-09-19Revised:2012-11-07Online:2013-07-02Published:2013-07-02 -

Contact:Sun Peng, M.D., Professor, Doctoral supervisor, Department of Neurosurgery, the Affiliated Hospital of Medical College, Qingdao University, Qingdao 266003, Shandong Province, China, 266003 sunpengqd@163.com -

About author:Fan Ming-chao★, Master, Attending physician, Department of Neurosurgical Intensive Care Unit, the Affiliated Hospital of Medical College, Qingdao University, Qingdao 266003, Shandong Province, China fanmcchina@126.com Wang Qiao-ling, Physician, Community Medical Service Center of Zhenjiang Road, Qingdao 266033, Shandong Province, China -

Supported by:Shandong Natural Science Foundation, No. z2008c06*; National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 81171208*

摘要:

背景:目前神经干细胞多由动物获得,不适合人类临床移植治疗。 目的:探索体外环境下人胚胎纹状体来源神经干细胞的培养方法,同时观察其生物学特性。 方法:取经水囊引产的孕8-16周人胚胎纹状体,体外用无血清DMEM培养基进行培养,待细胞形成神经球后进行传代,并应用含体积分数10%胎牛血清的DMEM/ F12培养液进行诱导分化。 结果与结论:体外培养的人胚胎纹状体来源神经干细胞生长迅速,表达神经干细胞标志物nestin。克隆形成实验显示细胞克隆形成率为6.0%-7.0%;BrdU掺入实验显示细胞增殖率为37.9%。免疫荧光染色显示经诱导分化的细胞表达神经元标志物Ⅲ型β微管蛋白、星形胶质细胞标志物胶质纤维酸性蛋白及神经干细胞标志物nestin,但不表达少突胶质细胞标志物髓鞘碱性蛋白。可见人胚胎纹状体来源神经干细胞在体外无血清条件下可保持其生物学特点,具有自我更新能力,经胎牛血清诱导后可向神经元及星形胶质细胞分化。

中图分类号:

引用本文

樊明超,王巧玲,刘 克,张 欣,关云谦,孙 鹏. 人胚胎纹状体来源神经干细胞的体外培养[J]. 中国组织工程研究, doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-4344.2013.27.016.

Fan Ming-chao, Wang Qiao-ling, Liu Ke, Zhang Xin, Guan Yun-qian, Sun Peng. In vitro culture of human embryonic striatum-derived neural stem cells[J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-4344.2013.27.016.

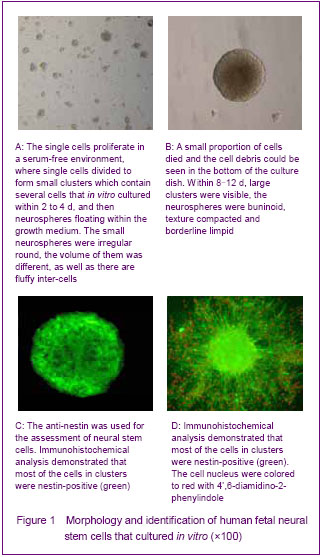

Culture and identification of human fetal neural stem cells

Single cells were isolated from the dissociated striatum of human 8-16 weeks old fetuses described above. The primary-generation cells were globular, and the percentage of living cells was more than 95% with tryphan blue staining. The cells were continued to proliferate in a serum-free environment, where single cells divided to form small clusters which contained several cells that in vitro cultured within 2 to 4 days, and then neurospheres floating within the growth medium were formed. The small neurospheres were irregular round; the volume of them was different as well as its fluffy inter-cells (Figure 1A). At the same time, small proportion of cells was died and the cell debris could be seen in the bottom of the culture dish. Within 8-12 days, large clusters were visible; the neurospheres were buninoid, texture compacted and borderline limpid (Figure 1B).

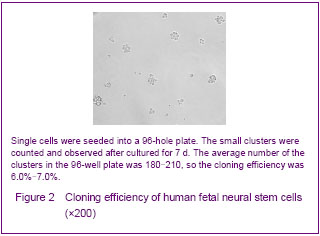

Cloning efficiency was used for analyzing the growth rates of human fetal neural stem cells, and the single cells were seeded into a 96-hole plate described above. The small clusters were counted and observed after cultured for 7 days (Figure 2). The average number of the clusters in the 96-hole plate was 180-210, so the cloning efficiency was 6.0%-7.0%.

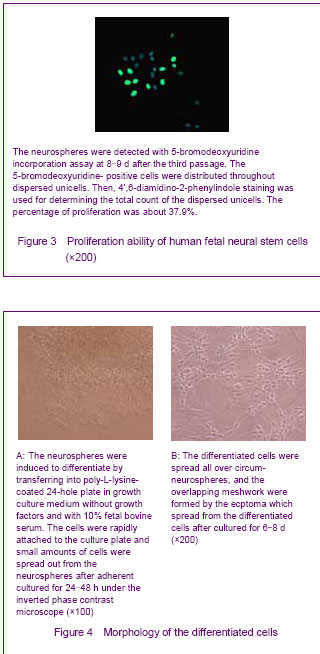

The neurospheres were induced to differentiate by transferring into poly-L-lysine-coated 24-hole plate in growth culture medium without growth factors and with 10% fetal bovine serum. The cells rapidly attached to the culture plate and small amounts of cells spread out from the neurospheres after adherent culture for 24-48 hours under the inverted phase contrast microscope. The cells were irregular and have short ecphymas (Figure 4A). The quantity of cells spread out from the neurospheres was increased with culturing, and the cells with different morphologies were apparent. The differentiated cells spread all over the circum-neurospheres, overlapping meshwork were formed by the ecptoma which spread from the differentiated cells after cultured for 6-8 days (Figure 4B).

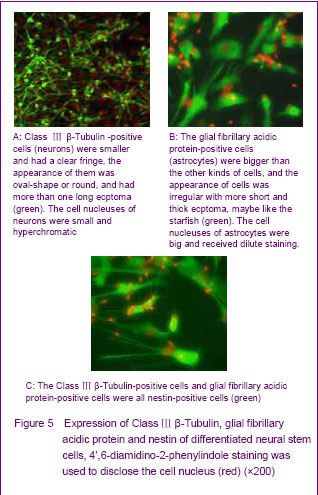

To further detect the differentiation ability of the human fetal neural stem cells, the anti-nestin, anti-myelin basic protein, anti-Class Ⅲ β-Tubulin and anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein were used for immunofluorescence labeling. Differentiated neurospheres were found containing different cell types. Class Ⅲ β-Tubulin-positive cells were smaller and had a clear fringe, the appearance of them was oval-shape or round, and had more than one long ecptoma (Figure 5A). The proportion of Class Ⅲ β-Tubulin-positive in differentiated neural stem cells separated from striatum was about 56.8%. The glial fibrillary acidic protein-positive cells were bigger than the other kind cells, and the appearance of them was irregular with short and thick ecptoma, maybe like the starfish (Figure 5B). The proportion of glial fibrillary acidic protein-positive in differentiated neural stem cells separated from striatum was about 39.8%. The myelin basic protein-positive cells were never seen in the differentiated neural stem cells that separated from striatum in our study. The nestin-positive cells were located on the interior neurospheres, and the number of circum-neurosphere was decreased (Figure 5C). The Class Ⅲ β-Tubulin-positive cells and glial fibrillary acidic protein-positive cells were all nestin-positive cells, but the fluorescence of differentiated cells was dimmish when compared with the cells before differentiation.

The Class Ⅲ β-Tubulin-positive cells had a tendency that they like aggregation when compared with the glial fibrillary acidic protein-positive cells. The glial fibrillary acidic protein-positive cells were hypodispersion in the corona radiata of differentiated neurospheres, but the Class Ⅲ β-Tubulin-positive cells could form cancellous cells cluster usually. The myelin basic protein-positive cells were unseen.

| [1] Cameron HA, Hazel TG, Mckay RD. Regulation of neurogenesis by growth factors and neurotransmitters. J Neurobiol. 1998;36(2):287-306.[2] Reynolds BA, Weiss S. Generation of neurons and astrocytes from isolated cells of the adult mammalian central nervous system. Science. 1992;255(5052): 1707-1710.[3] Temple S. The development of neural stem cells. Nature. 2001;414(6859):112-117.[4] Arsenijevic Y, Villemure JG, Brunet JF, et al. Isolation of multipotent neural precursors residing in the cortex of the adult human brain. Exp Neurol. 2001;170(1):48-62.[5] Park TI, Monzo H, Mee EW, et al. Adult human brain neural progenitor cells (NPCs) and fibroblast-like cells have similar properties in vitro but only NPCs differentiate into neurons. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e37742.[6] Johansson CB, Momma S, Clarke DL, et al. Identification of a neural stem cell in the adult mammalian central nervous system. Cell. 1999;96(1):25-34.[7] Xu R, Wu C, Tao Y, et al. Nestin-positive cells in the spinal cord: a potential source of neural stem cells. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2008;26(7):813-820.[8] Walton RM, Wolfe JH. In vitro growth and differentiation of canine olfactory bulb-derived neural progenitor cells under variable culture conditions. J Neurosci Methods. 2008; 169(1): 158-167.[9] Ryu KJ, Cho SJ, Hatori K, et al. Proactive transplantation of human neural stem cells prevents degeneration of striatal neurons in a rat model of Huntington disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;16(1):68-77.[10] Emborg ME, Ebert AD, Moirano J, et al. GDNF-secreting human neural progenitor cells increase tyrosine hydroxylase and VMAT2 expression in MPTP-treated cynomolgus monkeys. Cell Transplant. 2008;17(4):383-395.[11] Cusimano M, Biziato D, Brambilla E, et al. Transplanted neural stem/precursor cells instruct phagocytes and reduce secondary tissue damage in the injured spinal cord. Brain. 2012;135(Pt 2):447-460.[12] Xuan AG, Long DH, Yang DD, et al. BDNF improves the effects of neural stem cells on the rat model of Alzheimer's disease with unilateral lesion of fimbria-fornix. Neurosci Lett. 2008;440(3):331-335.[13] Xuan AG, Luo M, Ji WD, et al. Effects of engrafted neural stem cells in Alzheimer's disease rats. Neurosci Lett. 2009; 450(2):167-171.[14] Fauza DO, Jennings RW, Teng YD, et al. Neural stem cell delivery to the spinal cord in an ovine model of fetal surgery for spina bifida. Surgery. 2008;144(3):367-373.[15] Tsai RY, Mckay RD. Cell contact regulates fate choice by cortical stem cells. J Neurosci. 2000;20(10):3725-3735.[16] Schumm MA, Castellanos DA, Frydel BR, et al. Direct cell-cell contact required for neurotrophic effect of chromaffin cells on neural progenitor cells. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2003;146(1-2):1-13.[17] Wang JH, Hung CH, Young TH. Proliferation and differentiation of neural stem cells on lysine-alanine sequential polymer substrates. Biomaterials. 2006;27(18):3441-3450.[18] Tsai RY, Mckay RD. Cell contact regulates fate choice by cortical stem cells. J Neurosci. 2000;20(10):3725-3735.[19] Johansson CB, Svensson M, Wallstedt L, et al. Neural stem cells in the adult human brain. Exp Cell Res. 1999;253(2):733-736.[20] Castiglione M, Calafiore M, Costa L, et al. Group I metabotropic glutamate receptors control proliferation, survival and differentiation of cultured neural progenitor cells isolated from the subventricular zone of adult mice. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55(4):560-567.[21] Lin HJ, O’Shaughnessy TJ, Kelly J, et al. Neural stem cell differentiation in a cell-collagen-bioreactor culture system. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2004;153(2):163-173.[22] El Seady R, Huisman MA, Löwik CW, et al. Uncomplicated differentiation of stem cells into bipolar neurons and myelinating glia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008; 376(2):358-362.[23] Su L, Lü X, Xu J, et al. Neural stem cell differentiation is mediated by integrin beta 4 in vitro. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41(1):916-924.[24] Dictus C, Tronnier V, Unterberg A, et al. Comparative analysis of in vitro conditions for rat adult neural progenitor cells. J Neurosci Methods. 2007;161(2):250-258.[25] Hulspas R, Tiarks C, Reilly J, et al. In vitro cell density-dependent clonal growth of EGF-responsive murine neural progenitor cells under serum-free conditions. Exp Neurol. 1997;148(1):147-156.[26] Storch A, Sabolek M, Milosevic J, et al. Midbrain-derived neural stem cells; from basic science to therapeutic approaches. Cell Tissue Res. 2004;318(1):15-22.[27] Suzuki M, Wright LS, Marwah P, et al. Mitotic and neurogenic effects of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) on human neural stem cell cultures derived from the fetal cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(3):3203-3207.[28] Liu YH, Zhao LH, Zhao H, et al. The experimental research of culture of nueral stem cells isolated from rat fetal brain cortex in vitro. Zhongguo Shiyong Shenjing Jibing Zazhi. 2006;9(6):3-4.[29] Li X, Xu J, Bai Y, et al. Isolation and characterization of neural stem cells from human fetal striatum. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;326(2):425-434.[30] Bez A, Corsini E, Curti D, et al. Neurosphere and neurosphere-forming cells: morphological and ultrastructural characterization. Brain Res. 2003;993:18-19.[31] Itahana K, Campisi J, Dimri GP. Methods to detect biomarkers of cellular senescence: the senescence associated beta-galactosidase assay. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;371:21-31.[32] Ostenfeld T, Caldwell MA, Prowse KR, et al. Human neural precursor cells express low levels of telomerase in vitro and show diminishing cell proliferation with extensive axonal outgrowth following transplantation. Exp Neurol. 2000;164(1):215-226.[33] Wu P, Ye Y, Svendsen CN. Transduction of human neural progenitor cells using recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors. Gene Ther. 2002;9(4):245-255.[34] Sun Y, Pollard S, Conti L, et al. Long-term tripotent differentiation capacity of human neural stem (NS) cells in adherent culture. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2008;38(2):245-258.[35] Westerlund U, Moe MC, Varqhese M, et al. Stem cells from the adult human brain develop into functional neurons in culture. Exp Cell Res. 2003;289(2):378-383.[36] Xu R, Wu C, Tao Y, et al. Nestin-positive cells in the spinal cord: a potential source of neural stem cells. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2008;26(7):813-820.[37] Wang WZ, Qi JP, Wang DS, et al. Expression of glial fibrillar acidic protein and cyclinD1 in the perihematomal tissues in human hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage. Zhongfeng yu Shenjing Jibing Zazhi. 2008;25(2):158-160.[38] Roskams AJ, Cai X, Ronnett GV. Expression of neuron-specific beta-III tubulin during olfactory neurogenesis in the embryonic and adult rat. Neuroscience. 1998;83(1):191-200.[39] Yin XJ, Feng ZC, Du J, et al. Effects of neonatal calf serum on differentiation of human fetal neural stem cells in the hippocampus. Di Yi Jun Yi Da Xue Xue Bao. 2004;24(2):1164-1166.[40] Windrem MS, Nunes MC, Rashbaum WK, et al. Fetal and adult human oligodendrocyte progenitor cell isolates myelinate the congenitally dysmelinated brain. Nat med. 2004;10(1):93-97.[41] Murray K, Dubois-Daicq M. Emergence of oligodendrocytes from human neural spheres. J Neurosci Res. 1997;50(3):146-156.[42] Ostenfeld T, Joly E, Tai YT, et al. Regional specification of rodent and human neurospheres. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2002;134(2):43-55.[43] Chandran S, Compston A. Neural stem cells as a potential solll'ce ofoligodendrocytes for myelin repair. J Neurol Sci. 2005;233(1-2):178-181. |

| [1] | 蒲 锐, 陈子扬, 袁凌燕. 不同细胞来源外泌体保护心脏的特点与效应[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2021, 25(在线): 1-. |

| [2] | 张秀梅, 翟运开, 赵 杰, 赵 萌. 类器官模型国内外数据库近10年文献研究热点分析[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2021, 25(8): 1249-1255. |

| [3] | 王正东, 黄 娜, 陈婧娴, 郑作兵, 胡鑫宇, 李 梅, 苏 晓, 苏学森, 颜 南. 丁酸钠抑制氟中毒可诱导小胶质细胞活化及炎症因子表达增多[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2021, 25(7): 1075-1080. |

| [4] | 汪显耀, 关亚琳, 刘忠山. 提高间充质干细胞治疗难愈性创面的策略[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2021, 25(7): 1081-1087. |

| [5] | 万 然, 史 旭, 刘京松, 王岩松. 间充质干细胞分泌组治疗脊髓损伤的研究进展[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2021, 25(7): 1088-1095. |

| [6] | 廖成成, 安家兴, 谭张雪, 王 倩, 刘建国. 口腔鳞状细胞癌干细胞的治疗靶点及应用前景[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2021, 25(7): 1096-1103. |

| [7] | 谢文佳, 夏天娇, 周卿云, 刘羽佳, 顾小萍. 小胶质细胞介导神经元损伤在神经退行性疾病中的作用[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2021, 25(7): 1109-1115. |

| [8] | 李珊珊, 郭笑霄, 尤 冉, 杨秀芬, 赵 露, 陈 曦, 王艳玲. 感光细胞替代治疗视网膜变性疾病[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2021, 25(7): 1116-1121. |

| [9] | 焦 慧, 张一宁, 宋雨晴, 林 宇, 王秀丽. 乳腺癌类器官研究进展及临床应用前景[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2021, 25(7): 1122-1128. |

| [10] | 王诗琦, 张金生. 中医药调控缺血缺氧微环境对骨髓间充质干细胞增殖、分化及衰老的影响[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2021, 25(7): 1129-1134. |

| [11] | 曾燕华, 郝延磊. 许旺细胞体外培养及纯化的系统性综述[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2021, 25(7): 1135-1141. |

| [12] | 孔德胜, 何晶晶, 冯宝峰, 郭瑞云, Asiamah Ernest Amponsah, 吕 飞, 张舒涵, 张晓琳, 马 隽, 崔慧先. 间充质干细胞修复大动物模型脊髓损伤疗效评价的Meta分析[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2021, 25(7): 1142-1148. |

| [13] | 侯婧瑛, 于萌蕾, 郭天柱, 龙会宝, 吴 浩. 缺氧预处理激活HIF-1α/MALAT1/VEGFA通路促进骨髓间充质干细胞生存和血管再生[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2021, 25(7): 985-990. |

| [14] | 史洋洋, 秦英飞, 吴福玲, 何 潇, 张雪静. 胎盘间充质干细胞预处理预防小鼠毛细支气管炎[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2021, 25(7): 991-995. |

| [15] | 梁学奇, 郭黎姣, 陈贺捷, 武 杰, 孙雅琪, 邢稚坤, 邹海亮, 陈雪玲, 吴向未. 泡状棘球绦虫原头蚴抑制骨髓间充质干细胞向成纤维细胞的分化[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2021, 25(7): 996-1001. |

and degenerative disease[9-13]. A major limiting factor in the remedial transplantation of neural stem cells is the difficulty in supplying sufficient amounts of human fetal neural stem cells and the concomitant ethical issues associated with the use of human fetal tissues. A great deal of previous research found that the neural stem cells isolated from the central nervous system of embryo and adult mammalian could be propagated and differentiated in vitro[14-15]. Proliferation and differentiation of neural stem cells are affected by the internal and external signals coming from medium components, as well as some complex interactions among cells[16-18]. A reliable source of human neural stem cells would be of immense practical value to both foundation research and clinical neural transplantation trials.

.jpg)

100 mm culture capsule with 9 mL of a serum-free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium/F12 medium consisting 10 ng/mL human epidermal growth factor,

20 ng/mL human basic-fibroblast growth factor, 2% B27 supplement, 1% glutamine and 1% Penicillin- Streptomycin. The cells grew at 37 ℃ in 5% CO2 and 95% air with saturated humidity.

100 000 cells/mL using an improved neubauer counting plate.

24 hours until the neurospheres fixed on the plate. And the neurospheres cultured in the poly-L-lysine-coated 24-well plate until single cells spread from the neurospheres was considered as the second condition. Following fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde for

4-6 days until single cells spread from the cluster. The medium was replaced with 0.2 μmol/L 5-bromodeoxyuridine at 24 hours before fixture. Following fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde for 40 minutes, the cells were washed three times with 1% PBS-0.3% Triton X-100 at room temperature. Then the cells were incubated with

The proliferation and differentiation of the separated and cultured human embryonic striatum-derived neural stem cells were observed.

24 hours. At the same time, detection β-galactosidase activity is a classic staining to detect senile cell effectively on account of lysosomal enzyme β-galactosidase hyperergy to increase of content in the lysosome, and react with X-gal to display bluish-green[31]. The growth velocity will degrade gradualness along with the frequency of passage accrescence. Some biological substance such as telomerase and the different growing conditions demanded by diverse growth stage changed may be related[32].

1实验成功地从经水囊引产的孕8-16周人胚胎纹状体分离并体外培养扩增了适用于移植的人胚胎纹状体来源神经干细胞。 2 克隆形成率及BrdU掺入实验证实实验培养的人胚胎纹状体来源神经干细胞具有自我更新能力。 3 经胎牛血清诱导后人胚胎纹状体来源神经干细胞可向神经元及星形胶质细胞分化。 基金项目: 山东省自然科学基金项目(z2008c06);国家自然科学基金项目(81171208)。

专家意见1:材料和方法与以往文献报道类似,创新不大。

| 阅读次数 | ||||||

|

全文 |

|

|||||

|

摘要 |

|

|||||