中国组织工程研究 ›› 2024, Vol. 28 ›› Issue (25): 4072-4078.doi: 10.12307/2024.176

• 干细胞综述 stem cell review • 上一篇 下一篇

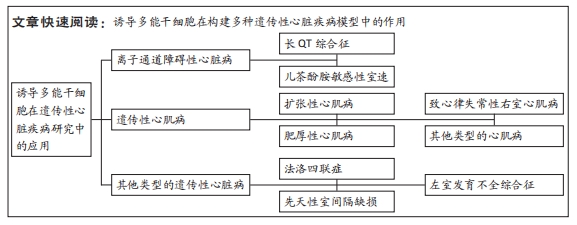

诱导多能干细胞在遗传性心脏疾病模型中的应用与机制

马阳光,张雅永,孟明耀,金志豪,李映明,黄耀萱,韩 燊,李亚雄

- 昆明医科大学附属昆明市延安医院,云南省昆明市 650051

-

收稿日期:2023-04-12接受日期:2023-06-21出版日期:2024-09-08发布日期:2023-11-24 -

通讯作者:李亚雄,主任医师,昆明医科大学附属昆明市延安医院,云南省昆明市 650051 韩燊,主治医师,昆明医科大学附属昆明市延安医院,云南省昆明市 650051 -

作者简介:马阳光,男,1998年生,青海省玛沁县人,回族,昆明医科大学附属延安医院心脏大血管外科在读硕士,主要从事先天性心脏病发病机制的研究。 -

基金资助:国家自然科学基金项目(82260063),项目负责人:韩燊;云南省心血管疾病重点实验室(2018DG008),项目负责人:李亚雄;云南省应用基础研究专项(202201AT070282),项目负责人:韩燊;云南省应用基础研究计划-昆医联合专项(202101AY070001-211),项目负责人:韩燊;云南省心血管系统疾病临床医学研究中心项目(202102AA310003-11),项目负责人:韩燊

Application and mechanism of induced pluripotent stem cells in inherited heart disease models

Ma Yangguang, Zhang Yayong, Meng Mingyao, Jin Zhihao, Li Yingming, Huang Yaoxuan, Han Shen, Li Yaxiong

- Yan’an Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University, Kunming 650051, Yunnan Province, China

-

Received:2023-04-12Accepted:2023-06-21Online:2024-09-08Published:2023-11-24 -

Contact:Li Yaxiong, Chief physician, Yan’an Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University, Kunming 650051, Yunnan Province, China Han Shen, Attending physician, Yan’an Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University, Kunming 650051, Yunnan Province, China -

About author:Ma Yangguang, Master candidate, Yan’an Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University, Kunming 650051, Yunnan Province, China -

Supported by:National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 82260063 (to HS); Key Laboratory of Cardiovascular Diseases of Yunnan Province, No. 2018DG008 (to LYX); Applied Basic Research Project of Yunnan Province, No. 202201AT070282 (to HS); Applied Basic Research Program - Kunming Medical Joint Special Project of Yunnan Province, No. 202101AY070001-211 (to HS); Clinical Medical Research Center Project of Cardiovascular System Disease of Yunnan, No. 202102AA310003-11 (to HS)

摘要:

文题释义:

诱导多能干细胞:是日本科学家Shinya Yamanaka等将4种重编程因子(c-Myc, Oct3/4,Sox2和 Klf4)导入体细胞产生的具有全能性的干细胞,现在已成为最理想的细胞模型之一。遗传性心脏病:主要指通过基因遗传给下一代所形成的心脏病,如肥厚型心肌病、扩张性心肌病、心律失常等疾病。

背景:遗传性心脏病具有较高的患病率及死亡率,至今其发病机制仍未阐明。尽管部分遗传性心脏病已经建立了相应的动物模型,为研究遗传性心脏病的发病机制提供了一定的基础,但是由于物种间的差异等原因显著降低了这些研究结果的价值,因此,需要全新的模型来探索其发生发展过程。

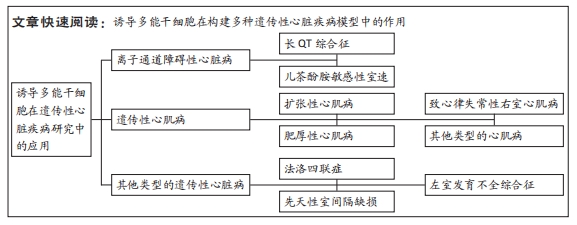

目的:综述了目前诱导多能干细胞在构建多种遗传性心脏病模型中的作用和潜在的应用前景。方法:第一作者于2023年1-3月期间应用计算机在PubMed数据库中检索近13年的相关文献,以“induced pluripotent stem cell,inherited heart disease,congenital heart disease”等为检索词,最终纳入76篇文献进行分析。

结果与结论:自2007年诱导多能干细胞从人体体细胞中诱导建立以来,已有许多针对疾病特异性诱导多能干细胞的研究报道。由于疾病特异性诱导多能干细胞能够再现疾病表型,因此有望成为体外疾病建模的一种新研究工具,用于分析发病机制和研制辅助药物。在心血管遗传性疾病的研究方面,从患者特异性诱导多能干细胞分化得到的心肌细胞中含有参与心脏发育异常相关的基因突变,因此,其可作为一种全新的工具研究遗传性心脏病的潜在机制。到目前为止,诱导多能干细胞来源心肌细胞已被广泛用于多种遗传性心脏疾病的分子机制研究,如心脏电生理性疾病、心肌病以及一些综合征性遗传性心脏疾病。

https://orcid.org/0009-0001-9756-961X (马阳光)

中国组织工程研究杂志出版内容重点:干细胞;骨髓干细胞;造血干细胞;脂肪干细胞;肿瘤干细胞;胚胎干细胞;脐带脐血干细胞;干细胞诱导;干细胞分化;组织工程

中图分类号:

引用本文

马阳光, 张雅永, 孟明耀, 金志豪, 李映明, 黄耀萱, 韩 燊, 李亚雄. 诱导多能干细胞在遗传性心脏疾病模型中的应用与机制[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2024, 28(25): 4072-4078.

Ma Yangguang, Zhang Yayong, Meng Mingyao, Jin Zhihao, Li Yingming, Huang Yaoxuan, Han Shen, Li Yaxiong. Application and mechanism of induced pluripotent stem cells in inherited heart disease models[J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2024, 28(25): 4072-4078.

保障。

2.2 iPSC在遗传性心脏病模型构建中的应用 iPSC技术的出现有助于加强人们对遗传性心脏病的遗传、分子和细胞机制的理解:首先,iPSC的应用基于人类疾病和独特的人类表型来研究细胞基因组学和表观遗传学的能力;其次,iPSC的可扩增等特性,能提高对低水平或瞬态信号分子的检测;最后,iPSC能研究在分子和细胞水平发育的相互作用,以及研究在组织水平的不同功能。基于上述这些优势,iPSC在遗传性心脏病的研究中具有广泛的应用前景。因此,作者对iPSC在遗传性心脏病中的应用进行了总结。

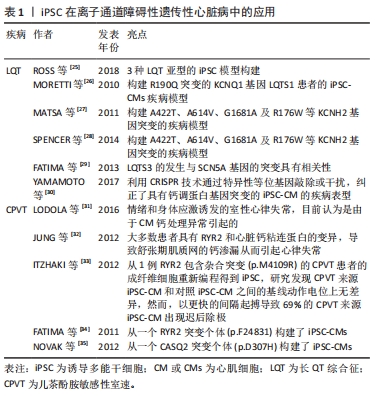

2.2.1 iPSC在离子通道障碍性遗传性心脏病中的应用 影响离子通道功能的基因突变是引起一系列疾病的原因,存在这些突变的患者会出现心律失常,目前已经报道的包括13种基因突变可能会影响离子在CM膜上的转移而导致心律失常的发生[24]。基于离子通道相关基因突变对CM生理学功能的影响更加明确以及较容易检测这些特点,iPSC在心律失常模型的研究中具有广泛的应用,见表1。

长QT综合征(long QT syndrome,LQT)表现为心电图QT间期延长,可能导致严重室性心律失常,由于室颤的发生和全身血压的大幅度下降,导致心脏骤停可引起晕厥和心脏猝死[36],主要包括LQTS1、LQTS2及LQTS3,最常见的2种类型是LQTS1和LQTS2,分别占所有患者的40%-55%和30%-35%,目前针对于3种LQTS中的iPSC模型均有报道[25]。MORETTI等[26]首次报道了携带R190Q突变的KCNQ1基因LQTS1患者的iPSC-CM疾病模型,来源于该iPSC的心房肌及心室肌细胞表现出持续延长的动作电位时间,也通过该模型证实了KCNQ1基因突变导致IKs电流异常引起LQTS,同时基于该模型也证实了其对β受体阻滞剂具有相同的反应。针对于LQTS2的iPSC-CM模型,目前已经报道了存在A422T、A614V、G1681A及R176W 等KCNH2基因突变的疾病模型[27-28],在CM水平LQT2来源的iPSC-CM同样表现出明显延长动作电位持续时间,以及明显异常的IKr电流,基于该模型已经研究了心律失常预防剂对LQT2-iPSC-CM的作用,包括ICa,L抑制剂硝苯地平,IK,ATP通道开放剂吡那地尔和尼可地尔,IKr通道增强剂PD-118057,这些药物的使用显著降低了iPSC-CM的动作电位持续时间,很好地模拟了LQT2对治疗药物的临床反应,为个体化治疗提供了帮助。LQTS3的发生与SCN5A基因的突变具有相关性,该基因的突变导致了Na+持续向内电流(INa)引起了动作电位平台期和QT间期的延长,来自具有SCN5A1795insD/+突变的患者iPSC-CM模型细胞膜片钳检测显示INa+密度显著降低,INa+峰值-30 mV处的密度仅仅是对照组CM的46%,同时动作电位检测发现LQTS3-iPSC-CM的Vmax明显降低且具有较长的90%复极化的动作电位持续时间[29],该iPSC-CM模型将有益于研究SCN5A突变导致的遗传性心脏病,如Brugada综合征等。在未来的临床转化方面,基于iPSC平台以及相关致病基因的发现,近年来有研究利用CRISPR技术通过特异性等位基因敲除或干扰,纠正了具有钙调蛋白基因突变的iPSC-CM的疾病表型[30],这些研究证明了使用LQTS患者iPSC衍生的CM模拟疾病表型并提供新疗法的潜力。

儿茶酚胺敏感性室速(catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia,CPVT)是一种遗传性心律失常,其特征在于情绪和身体应激诱发的室性心律失常,目前认为是由于CM钙处理异常引起的[31]。大多数患者具有RYR2和心脏钙粘连蛋白(CASQ2)的变异,导致舒张期肌质网的钙渗漏从而引起心律失常[32]。 然而,这些变异导致钙离子释放缺陷的确切机制尚不完全清楚,而iPSC-CM为研究CPVT提供了一个新的平台。ITZHAKI等[33]从1例RYR2包含杂合突变(p.M4109R)的CPVT患者的成纤维细胞重新编程得到iPSC,研究发现CPVT来源iPSC-CM和对照iPSC-CM之间的基线动作电位上无差异,然而,以更快的间隔起搏导致69%的CPVT来源iPSC-CM出现迟后除级(DAD),而健康对照iPSC-CM的这一比例仅为11%,此外,作者通过钙成像证明,肾上腺素能的刺激和更高的钙浓度可以通过更快的起搏对心肌钙瞬变造成影响,使其加剧。FATIMA等[34]和NOVAK等[35]发现类似的结果,他们分别从另一个RYR2突变个体(p.F24831)和CASQ2突变个体(p.D307H)构建了iPSC-CMs,获得了相同的结果,表明异丙肾上腺素对心律失常和舒张期钙离子升高的倾向增加。同时,基于这些模型发现了丹曲林、毒胡萝卜素(细胞内钙释放剂)、S107(RYR稳定剂)、CAMKII抑制剂、普萘洛尔等均能改善CPVT的疾病表型,这些结果表明疾病特异性iPSC在未来将可用于遗传心律失常疾病的药物筛选中。

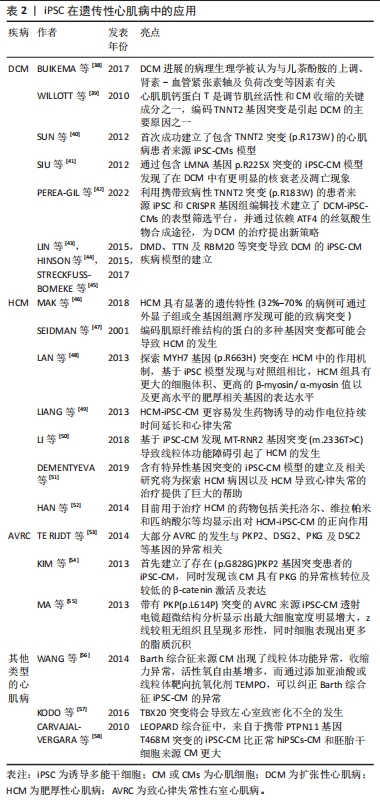

2.2.2 iPSC在遗传性心肌病中的应用 遗传性心肌病的发生与基因突变等异常导致CM功能改变有显著的相关性,但是由于心肌疾病在体内复杂的发生发展过程,以及对细胞病理生理学的研究不足,阻碍了心肌病疾病模型的构建,因此心肌病的病因学仍未阐明。基于膜片钳等工具对CM电生理特性的有效检测,iPSC在心律失常性疾病中得到了广泛的应用,然而,iPSC-CM是否可以对心肌病进行功能建模,是否可以在体外分析收缩功能异常以验证心肌病的细胞表型,这些都存在较大的疑问。随着目前检测手段的不断提高,iPSC在心肌病的体外研究中已得到了广泛的应用[37],见表2。

扩张性心肌病(dilated cardiomyopathy,DCM)是一种进行性心室扩张和收缩功能下降的疾病,通常导致心力衰竭综合征,并可能发展为致命性心律失常。DCM进展的病理生理学被认为与儿茶酚胺的上调、肾素-血管紧张素轴及负荷改变等因素有关[38],DCM属于混合型心肌病,家族性遗传性DCM约占35%。由于DCM患者心脏标本采集困难,培养的CM存活时间短等因素,限制了对DCM的研究。心肌肌钙蛋白T是调节肌丝活性和CM收缩的关键成分之一,编码TNNT2基因的突变是引起DCM的主要原因之一[39],2012年SUN等[40]首次成功建立了包含TNNT2突变(p.R173W)的心肌病患者来源iPSC-CMs模型,对其表型进行检测后发现与对照组相比,DCM-iPSC-CM中出现肌动蛋白较多呈点状分布、Z线排列混乱等超微结构的异常,且在功能上表现为收缩功能的降低;同时,作者证明了去甲肾上腺素治疗可导致DCM表型恶化,而美托洛尔治疗具有保护作用,从而在细胞水平反映了各种药物在DCM中的临床效果。LMNA突变与DCM的发生具有相关性,SIU等[41]通过包含LMNA 基因p.R225X突变的iPSC-CM模型发现了在DCM中有更明显的核衰老及凋亡现象。2022年由PEREA-GIL等[42]发表的一篇文章报道了他们利用携带致病性TNNT2突变(p.R183W)的患者来源iPSC和CRISPR基因组编辑技术建立了DCM-iPSC-CMs的表型筛选平台,并通过依赖ATF4的丝氨酸生物合成途径,为DCM的治疗提出新策略。目前更多基因如DMD、TTN及RBM20等突变构建DCM的iPSC-CM疾病模型[43-45],为探索DCM的病理生理学机制提供了巨大平台。目前DCM-iPSC-CMs也已被用于评估基因治疗方法的疗效,研究发现SERCA2A过表达能减少DCM相关的细胞异常[40],这些发现将为特异性疾病治疗手段的研究提供新的思路。

肥厚性心肌病(hypertrophic cardiomyopathy,HCM)是一种主要表现为左心室壁异常增厚的疾病,同样也会导致心力衰竭综合征和致命的心律失常。HCM具有显著的遗传特性(32%-70%的病例可通过外显子组或全基因组测序发现可能的致病突变) [46],编码肌原纤维结构的蛋白的多种基因突变都可能会导致HCM的发生[47],但是由于HCM缺乏相应的模型,至今其致病机制仍未阐明,也未能发现有效改善HCM的相关药物。LAN等[48]为探索MYH7基因(p.R663H)突变在HCM中的作用机制,基于iPSC模型发现与对照组相比,HCM组具有更大的细胞体积、更高的β-myosin/α-myosin值以及更高水平的肥厚相关基因的表达水平,同时作者指出钙摄取受损及细胞内舒张期钙浓度升高与细胞肥大和心律失常负荷有关。同样,基于iPSC模型,LIANG等[49]报道HCM-iPSC-CM更容易发生药物诱导的动作电位持续时间延长和心律失常。LI等[50]基于iPSC-CM发现MT-RNR2基因突变(m.2336T > C)导致线粒体功能障碍引起了HCM的发生。随着大量含有特异性基因突变的iPSC-CM模型的建立及相关研究,将为探索HCM相关的病因以及HCM导致心律失常的治疗提供了巨大的帮助[51]。目前用于治疗HCM的药物包括美托洛尔、维拉帕米和匹纳酸尔等均显示出对HCM-iPSC-CM的正向作用[52],这些结果体现了iPSC-CM模型在HCM治疗药物研究和开发中的潜在应用。

致心律失常性右室心肌病(arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy,AVRC)是一种主要导致右心室动脉瘤和纤维脂肪浸润的遗传性原发性心肌病。大部分AVRC的发生与PKP2、DSG2、PKG及DSC2等基因的异常相关[53]。目前,针对于AVRC来源iPSC-CM的建立主要是来源于PKP2基因突变的患者。2013年KIM等[54]首先建立了存在(p.G828G)PKP2基因突变患者的iPSC-CM,同时发现该CM具有PKG的异常核转位及较低的β-catenin激活及表达,还发现虽然具有PKP2突变的iPSC-CM在正常培养条件下未显示出病理表型,但当培养基补充相应的因子诱导脂肪生成途径活化时,CM显示脂肪生成和细胞凋亡增加。而MA等[55]研究发现带有PKP(p.L614P)突变的AVRC来源iPSC-CM透射电镜超微结构分析显示出最大细胞宽度明显增大,z线较粗无组织且呈现多形性,同时细胞表现出更多的脂质沉积。由于AVRC为一种组织水平的疾病且发病年龄较大,在使用iPSC-CM探索过程中虽然存在CM成熟性较差等问题,但是ARVC细胞模型概括了疾病表型的关键特征,为进一步了解其潜在机制以及评估其在诊断和治疗中的新临床应用提供了平台。

其他类型的心肌病如线粒体功能障碍性的Barth综合征(Barth syndrome)是由TAZ基因突变引起的,该基因在线粒体结构中起着重要作用,该基因的突变将导致线粒体结构和功能异常,基于iPSC模型,WANG等[56]发现了Barth综合征来源CM出现了线粒体功能异常,收缩力异常,活性氧自由基增多,而通过添加亚油酸或线粒体靶向抗氧化剂TEMPO,可以纠正Barth综合征iPSC-CM的异常。KODO等[57]发现TBX20突变将会导致左心室致密化不全(left ventricular non-compaction,LVNC)的发生,基于iPSC-CM模型,发现TBX20异常将导致转化生长因子β信号通路的异常激活,从而影响CM的增殖能力等,在心肌分化过程中抑制转化生长因子β信号通路能有效纠正细胞表型的改变。LEOPARD综合征是一种常染色体显性遗传病,以肥厚性心肌病为重要临床表现。大约有90%的LEOPARD综合征病例是由于编码酪氨酸磷酸酶SHP2的PTPN11基因发生了错误的突变,CARVAJAL-VERGARA等[58]发现来自于携带PTPN11基因T468M突变的iPSC-CM比正常hiPSCs-CM和胚胎干细胞来源CM更大。

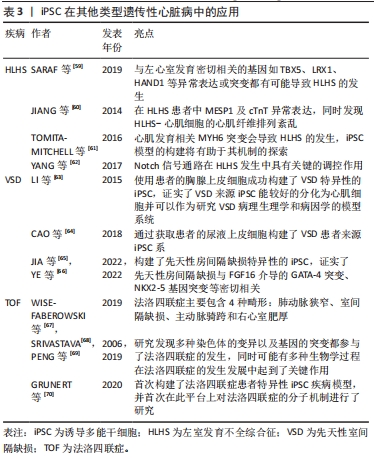

2.2.3 iPSC在其他类型遗传性心脏病中的应用 一些结构异常性的遗传性心脏病可能与不正常发育的CM和功能失调的心血管细胞有关,基于iPSC能较好维持患者的遗传学背景且能较好模拟心脏的发育过程,从而探索基因突变对细胞功能的影响,因此在这些先天性心脏病中也有广泛的应用前景,见表3。

左室发育不全综合征(hypoplastic left heart syndrome,HLHS)是一种严重的先天性心血管结构畸形,其特征是左心结构发育不全,包括左心室发育不全或闭锁、升主动脉、主动脉瓣和二尖瓣发育异常。HLHS是婴幼儿心脏移植最常见的原因,是导致儿童死亡的心血管畸形。目前认为与左心室发育密切相关的基因如TBX5、LRX1、HAND1等异常表达或突变都有可能导致HLHS的发生[59]。同样,iPSC模型的建立为探索HLHS的发生提供了平台。基于iPSC-CM模型,JIANG等[60]发现了在HLHS患者中MESP1及cTnT的异常表达,同时发现了HLHS-CM的心肌纤维排列紊乱;TOMITA-MITCHELL等[61]发现心肌发育相关MYH6突变会导致HLHS的发生,iPSC模型的构建将有助于其机制的探索;YANG等[62]发现了Notch信号通路在HLHS发生中具有关键的调控作用,在HLHS来源iPSC向CM分化过程中给予Notch信号通路激活剂将明显改善心肌分化能力及搏动速率,抑制了平滑肌细胞的形成。以上这些基于iPSC研究表明从HLHS-iPSC系衍生的CM存在发育和/或功能缺陷,这些缺陷可能损害其在体内参与心肌发生的能力,未来基于该平台将进一步研究HLHS病因学中涉及的分子机制。

其他类型的先天性心脏病如先天性室间隔缺损(ventricular septal defect,VSD)是由基因突变或环境因素共同作用引起的最常见的先天性心脏疾病,至今其发病机制仍未阐明,基因突变如GATA4、NKX2.5等均可导致其发生。LI等[63]通过使用患者的胸腺上皮细胞成功构建了VSD特异性的iPSC,证实了 VSD来源iPSC能较好地分化为CM并可以作为研究VSD病理生理学和病因学的模型系统。CAO等[64]通过获取患者的尿液上皮细胞构建了VSD患者来源iPSC系,同时发现该细胞存在RYR2基因的L2483R突变,将为探索VSD引起心力衰竭的发病机制、药物治疗和基因治疗提供坚实的平台。目前,基于iPSC平台对常见的先天性结构性心脏病的报道仍较少,但是相信随着对存在基因突变患者的个体化研究及治疗的进一步发展,iPSC应用将会有广泛的应用前景。不仅是VSD,先天性房间隔缺损的发生发展与基因突变相关性很高,有学者构建了先天性房间隔缺损特异性的iPSC,证实了先天性房间隔缺损与FGF16介导的GATA-4突变、NKX2-5基因突变等密切相关[65-66]。

法洛四联症是最常见的发绀型先天性心脏病,主要包含4种畸形:肺动脉狭窄、室间隔缺损、主动脉骑跨和右心室肥厚[67],其发病机制较为复杂,目前有学者研究发现多种染色体的变异以及基因的突变都参与了法洛四联症的发生,同时可能有多种生物学过程在法洛四联症的发生发展中起到了关键作用[68-69]。2020年,在GRUNERT等[70]发表的一篇文章中首次构建了法洛四联症患者特异性iPSC疾病模型,并首次在此平台上对法洛四联症的分子机制进行了研究,在法洛四联症来源iPSC-CM与健康亲属对照间观察到明显的转录差异,这一差异在分化后期更为明显,不仅如此,对iPSC和诱导分化后的iPSC-CM进行RNAseq分析证实法洛四联症确有潜在的基因上调与下调。法洛四联症iPSC模型的构建将法洛四联症基本病因的研究带到了新的高度,有望在该疾病的深入研究方面发挥巨大的作用,并且为法洛四联症的预防和分子治疗提供新的依据。

| [1] DASTGIRI S, STONE DH, LE-HA C, et al. Prevalence and secular trend of congenital anomalies in Glasgow, UK. Arch Dis Child. 2002;86(4):257-263. [2] TENNANT PW, PEARCE MS, BYTHELL M, et al. 20-year survival of children born with congenital anomalies: a population-based study. Lancet. 2010; 375(9715):649-656. [3] LIU Y, CHEN S, ZÜHLKE L, et al. Global birth prevalence of congenital heart defects 1970-2017: updated systematic review and meta-analysis of 260 studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2019;48(2):455-463. [4] OTTAVIANI G, BUJA LM. Update on congenital heart disease and sudden infant/perinatal death: from history to future trends. J Clin Pathol. 2017; 70(7):555-562. [5] WILLIAMS K, CARSON J, LO C. Genetics of Congenital Heart Disease. Biomolecules. 2019;9(12):879. [6] TAKAHASHI K, YAMANAKA S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126(4):663-676. [7] TAKAHASHI K, TANABE K, OHNUKI M, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131(5): 861-872. [8] DIMOS JT, RODOLFA KT, NIAKAN KK, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells generated from patients with ALS can be differentiated into motor neurons. Science. 2008;321(5893):1218-1221. [9] KAMBAL A, MITCHELL G, CARY W, et al. Generation of HIV-1 resistant and functional macrophages from hematopoietic stem cell-derived induced pluripotent stem cells. Mol Ther. 2011;19(3):584-593. [10] MORDWINKIN NM, BURRIDGE PW, WU JC. A review of human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes for high-throughput drug discovery, cardiotoxicity screening, and publication standards. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2013;6(1):22-30. [11] AVIOR Y, SAGI I, BENVENISTY N. Pluripotent stem cells in disease modelling and drug discovery. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016;17(3):170-182. [12] NGUYEN HN, BYERS B, CORD B, et al. LRRK2 mutant iPSC-derived DA neurons demonstrate increased susceptibility to oxidative stress. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8(3):267-280. [13] YANG J, LI S, HE XB, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells in Alzheimer’s disease: applications for disease modeling and cell-replacement therapy. Mol Neurodegener. 2016;11(1):39. [14] YOSHIDA Y, YAMANAKA S. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells 10 Years Later: For Cardiac Applications. Circ Res. 2017;120(12):1958-1968. [15] ROSE RA, JIANG H, WANG X, et al. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells express cardiac-specific markers, retain the stromal phenotype, and do not become functional cardiomyocytes in vitro. Stem Cells. 2008; 26(11):2884-2892. [16] KEHAT I, KENYAGIN-KARSENTI D, SNIR M, et al. Human embryonic stem cells can differentiate into myocytes with structural and functional properties of cardiomyocytes. J Clin Invest. 2001;108(3):407-414. [17] VERMA V, PURNAMAWATI K, MANASI, et al. Steering signal transduction pathway towards cardiac lineage from human pluripotent stem cells: a review. Cell Signal. 2013;25(5):1096-1107. [18] TALKHABI M, AGHDAMI N, BAHARVAND H. Human cardiomyocyte generation from pluripotent stem cells: A state-of-art. Life Sci. 2016;145: 98-113. [19] BURRIDGE PW, MATSA E, SHUKLA P, et al. Chemically defined generation of human cardiomyocytes. Nat Methods. 2014;11(8):855-860. [20] PAIGE SL, PLONOWSKA K, XU A, et al. Molecular regulation of cardiomyocyte differentiation. Circ Res. 2015;116(2):341-353. [21] GRAICHEN R, XU X, BRAAM SR, et al. Enhanced cardiomyogenesis of human embryonic stem cells by a small molecular inhibitor of p38 MAPK. Differentiation. 2008;76(4):357-370. [22] LIAN X, ZHANG J, AZARIN SM, et al. Directed cardiomyocyte differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells by modulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling under fully defined conditions. Nat Protoc. 2013;8(1):162-175. [23] CAO N, LIANG H, HUANG J, et al. Highly efficient induction and long-term maintenance of multipotent cardiovascular progenitors from human pluripotent stem cells under defined conditions. Cell Res. 2013;23(9): 1119-1132. [24] MÜLLER M, SEUFFERLEIN T, ILLING A, et al. Modelling human channelopathies using induced pluripotent stem cells: a comprehensive review. Stem Cells Int. 2013;2013:496501. [25] ROSS SB, FRASER ST, SEMSARIAN C. Induced pluripotent stem cell technology and inherited arrhythmia syndromes. Heart Rhythm. 2018; 15(1):137-144. [26] MORETTI A, BELLIN M, WELLING A, et al. Patient-specific induced pluripotent stem-cell models for long-QT syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2010; 363(15):1397-1409. [27] MATSA E, RAJAMOHAN D, DICK E, et al. Drug evaluation in cardiomyocytes derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells carrying a long QT syndrome type 2 mutation. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(8):952-962. [28] SPENCER CI, BABA S, NAKAMURA K, et al. Calcium transients closely reflect prolonged action potentials in iPSC models of inherited cardiac arrhythmia. Stem Cell Reports. 2014;3(2):269-281. [29] FATIMA A, KAIFENG S, DITTMANN S, et al. The disease-specific phenotype in cardiomyocytes derived from induced pluripotent stem cells of two long QT syndrome type 3 patients. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e83005. [30] YAMAMOTO Y, MAKIYAMA T, HARITA T, et al. Allele-specific ablation rescues electrophysiological abnormalities in a human iPS cell model of long-QT syndrome with a CALM2 mutation. Hum Mol Genet. 2017;26(9): 1670-1677. [31] LODOLA F, MORONE D, DENEGRI M, et al. Adeno-associated virus-mediated CASQ2 delivery rescues phenotypic alterations in a patient-specific model of recessive catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7(10):e2393. [32] JUNG CB, MORETTI A, MEDEROS Y SCHNITZLER M, et al. Dantrolene rescues arrhythmogenic RYR2 defect in a patient-specific stem cell model of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. EMBO Mol Med. 2012;4(3):180-191. [33] ITZHAKI I, MAIZELS L, HUBER I, et al. Modeling of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia with patient-specific human-induced pluripotent stem cells. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(11):990-1000. [34] FATIMA A, XU G, SHAO K, et al. In vitro modeling of ryanodine receptor 2 dysfunction using human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2011;28(4):579-592. [35] NOVAK A, BARAD L, ZEEVI-LEVIN N, et al. Cardiomyocytes generated from CPVTD307H patients are arrhythmogenic in response to beta-adrenergic stimulation. J Cell Mol Med. 2012;16(3):468-482. [36] MOSS AJ, SCHWARTZ PJ, CRAMPTON RS, et al. The long QT syndrome. Prospective longitudinal study of 328 families. Circulation. 1991;84(3): 1136-1144. [37] ESCHENHAGEN T, CARRIER L. Cardiomyopathy phenotypes in human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes-a systematic review. Pflugers Arch. 2019;471(5):755-768. [38] BUIKEMA JW, WU SM. Untangling the Biology of Genetic Cardiomyopathies with Pluripotent Stem Cell Disease Models. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2017;19(4):30. [39] WILLOTT RH, GOMES AV, CHANG AN, et al. Mutations in Troponin that cause HCM, DCM AND RCM: what can we learn about thin filament function? J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;48(5):882-892. [40] SUN N, YAZAWA M, LIU J, et al. Patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells as a model for familial dilated cardiomyopathy. Sci Transl Med. 2012; 4(130):130ra47. [41] SIU CW, LEE YK, HO JC, et al. Modeling of lamin A/C mutation premature cardiac aging using patient‐specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Aging (Albany NY). 2012;4(11):803-822. [42] PEREA-GIL I, SEEGER T, BRUYNEEL AAN, et al. Serine biosynthesis as a novel therapeutic target for dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(36): 3477-3489. [43] LIN B, LI Y, HAN L, et al. Modeling and study of the mechanism of dilated cardiomyopathy using induced pluripotent stem cells derived from individuals with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Dis Model Mech. 2015;8(5):457-466. [44] HINSON JT, CHOPRA A, NAFISSI N, et al. HEART DISEASE. Titin mutations in iPS cells define sarcomere insufficiency as a cause of dilated cardiomyopathy. Science. 2015;349(6251):982-986. [45] STRECKFUSS-BÖMEKE K, TIBURCY M, FOMIN A, et al. Severe DCM phenotype of patient harboring RBM20 mutation S635A can be modeled by patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2017;113:9-21. [46] MAK TSH, LEE YK, TANG CS, et al. Coverage and diagnostic yield of Whole Exome Sequencing for the Evaluation of Cases with Dilated and Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):10846. [47] SEIDMAN JG, SEIDMAN C. The genetic basis for cardiomyopathy: from mutation identification to mechanistic paradigms. Cell. 2001;104(4):557-567. [48] LAN F, LEE AS, LIANG P, et al. Abnormal calcium handling properties underlie familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy pathology in patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12(1):101-113. [49] LIANG P, LAN F, LEE AS, et al. Drug screening using a library of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes reveals disease-specific patterns of cardiotoxicity. Circulation. 2013;127(16):1677-1691. [50] LI S, PAN H, TAN C, et al. Mitochondrial Dysfunctions Contribute to Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy in Patient iPSC-Derived Cardiomyocytes with MT-RNR2 Mutation. Stem Cell Reports. 2018;10(3):808-821. [51] DEMENTYEVA EV, MEDVEDEV SP, KOVALENKO VR, et al. Applying Patient-Specific Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells to Create a Model of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Biochemistry (Mosc). 2019;84(3):291-298. [52] HAN L, LI Y, TCHAO J, et al. Study familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy using patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Cardiovasc Res. 2014;104(2):258-269. [53] TE RIJDT WP, JONGBLOED JD, DE BOER RA, et al. Clinical utility gene card for: arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC). Eur J Hum Genet. 2014;22(2). doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2013.124. [54] KIM C, WONG J, WEN J, et al. Studying arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia with patient-specific iPSCs. Nature. 2013;494(7435):105-110. [55] MA D, WEI H, LU J, et al. Generation of patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes as a cellular model of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(15):1122-1133. [56] WANG G, MCCAIN ML, YANG L, et al. Modeling the mitochondrial cardiomyopathy of Barth syndrome with induced pluripotent stem cell and heart-on-chip technologies. Nat Med. 2014;20(6):616-623. [57] KODO K, ONG SG, JAHANBANI F, et al. iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes reveal abnormal TGF-β signalling in left ventricular non-compaction cardiomyopathy. Nat Cell Biol. 2016;18(10):1031-1042. [58] CARVAJAL-VERGARA X, SEVILLA A, D’SOUZA SL, et al. Patient-specific induced pluripotent stem-cell-derived models of LEOPARD syndrome. Nature. 2010;465(7299):808-812. [59] SARAF A, BOOK WM, NELSON TJ, et al. Hypoplastic left heart syndrome: From bedside to bench and back. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2019;135:109-118. [60] JIANG Y, HABIBOLLAH S, TILGNER K, et al. An induced pluripotent stem cell model of hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) reveals multiple expression and functional differences in HLHS-derived cardiac myocytes. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2014;3(4):416-423. [61] TOMITA-MITCHELL A, STAMM KD, MAHNKE DK, et al. Impact of MYH6 variants in hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Physiol Genomics. 2016;48(12): 912-921. [62] YANG C, XU Y, YU M, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell modelling of HLHS underlines the contribution of dysfunctional NOTCH signalling to impaired cardiogenesis. Hum Mol Genet. 2017;26(16):3031-3045. [63] LI J, CAO YY, MA XJ, et al. Thymic derived iPs cells can be differentiated into cardiomyocytes. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2015;20(6):964-974. [64] CAO Y, XU J, WEN J, et al. Generation of a Urine-Derived Ips Cell Line from a Patient with a Ventricular Septal Defect and Heart Failure and the Robust Differentiation of These Cells to Cardiomyocytes via Small Molecules. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;50(2):538-551. [65] JIA L, LIMENG D, XIAOYIN T, et al. A Novel Splicing Mutation c.335-1 G > A in the Cardiac Transcription Factor NKX2-5 Leads to Familial Atrial Septal Defect Through miR-19 and PYK2. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2022;18(8): 2646-2661. [66] YE L, YU Y, ZHAO ZA, et al. Patient-specific iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes reveal abnormal regulation of FGF16 in a familial atrial septal defect. Cardiovasc Res. 2022;118(3):859-871. [67] WISE-FABEROWSKI L, ASIJA R, MCELHINNEY DB. Tetralogy of Fallot: Everything you wanted to know but were afraid to ask. Paediatr Anaesth. 2019;29(5):475-482. [68] SRIVASTAVA D. Making or breaking the heart: from lineage determination to morphogenesis. Cell. 2006;126(6):1037-1048. [69] PENG R, ZHENG J, XIE HN, et al. Genetic anomalies in fetuses with tetralogy of Fallot by using high-definition chromosomal microarray analysis. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2019;17(1):8. [70] GRUNERT M, APPELT S, SCHÖNHALS S, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells of patients with Tetralogy of Fallot reveal transcriptional alterations in cardiomyocyte differentiation. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):10921. [71] KARAKIKES I, AMEEN M, TERMGLINCHAN V, et al. Human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes: insights into molecular, cellular, and functional phenotypes. Circ Res. 2015;117(1):80-88. [72] CHONG JJ, YANG X, DON CW, et al. Human embryonic-stem-cell-derived cardiomyocytes regenerate non-human primate hearts. Nature. 2014;510(7504):273-277. [73] KREUTZER J, VIEHRIG M, PÖLÖNEN RP, et al. Pneumatic unidirectional cell stretching device for mechanobiological studies of cardiomyocytes. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2020;19(1):291-303. [74] GARBERN JC, HELMAN A, SEREDA R, et al. Inhibition of mTOR Signaling Enhances Maturation of Cardiomyocytes Derived From Human-Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells via p53-Induced Quiescence. Circulation. 2020;141(4):285-300. [75] VELDHUIZEN J, CUTTS J, BRAFMAN DA, et al. Engineering anisotropic human stem cell-derived three-dimensional cardiac tissue on-a-chip. Biomaterials. 2020;256:120195. [76] WU P, DENG G, SAI X, et al. Maturation strategies and limitations of induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Biosci Rep. 2021; 41(6):BSR20200833. |

| [1] | 尹功华, 徐若瑶, 张丽娟, 张一凡, 齐 洁, 张 钧. m6A甲基化修饰非编码RNA调控病理性心脏重塑的作用[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2024, 28(20): 3252-2358. |

| [2] | 崔胜男, 刘传国, 杨雯晴, 郑志娟, 张 丹. 毛蕊异黄酮对人诱导多能干细胞内皮分化的影响及机制[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2024, 28(19): 3031-3036. |

| [3] | 迟宏扬, 杨慧霞, 郝银菊, 杨安宁, 白志刚, 焦 运, 熊建团, 马胜超, 姜怡邓. 缺氧后处理通过piRNA-005854调控衰老心肌细胞自噬发挥保护心肌作用[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2024, 28(13): 2054-2060. |

| [4] | 杨慧霞, 揭育祯, 白志刚, 焦 运, 杨 勇, 马天龙, 马胜超, 姜怡邓. LncRNA MALAT1在衰老大鼠心肌缺血后处理自噬水平降低中的作用[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2023, 27(20): 3173-3179. |

| [5] | 范清华, 齐 洁, 张 钧. Hippo-YAP信号通路在运动性心肌肥大中的调控作用[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2023, 27(17): 2708-2715. |

| [6] | 王雪娇, 史文娟, 张 燕, 邢德海, 李冬雪, 焦向英. 硫氧还蛋白相互作用蛋白介导的炎症反应及细胞凋亡在心肌梗死中的作用[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2023, 27(11): 1715-1721. |

| [7] | 武霄雷, 韩 瑜, 李佳蕾, 王 霜, 曹济民, 孙 腾. piRNA-5938可调控心肌细胞凋亡和线粒体分裂[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2023, 27(11): 1750-1757. |

| [8] | 黄文俊, 王 洁, 周亚飞, 李 环, 蒋丛姗, 张艳敏, 周 锐. 一种人诱导多能干细胞向内皮细胞定向分化方案的建立及鉴定[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2023, 27(10): 1553-1559. |

| [9] | 黄文俊, 周亚飞, 王 洁, 李 环, 张艳敏, 周 锐. 建立并鉴定一种基于人诱导多能干细胞的肝脏细胞定向分化实验方案[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2023, 27(1): 28-33. |

| [10] | 熊挺淋, 应梦慧, 张丽莎, 张晓刚, 杨 燕. 诱导多能干细胞分化的心肌细胞电生理特点[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2022, 26(7): 1063-1067. |

| [11] | 蒲 锐, 陈子扬, 袁凌燕. 不同细胞来源外泌体保护心脏的特点与效应[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2021, 25(在线): 1-. |

| [12] | 裴丽丽, 孙贵才, 王 弟. 丹酚酸B抑制骨髓间充质干细胞氧化损伤及促进分化为心肌样细胞[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2021, 25(7): 1032-1036. |

| [13] | 蒲 锐, 陈子扬, 袁凌燕. 不同细胞来源外泌体保护心脏的特点与效应[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2021, 25(31): 5065-5071. |

| [14] | 韦云剑, 张风波, 龙 平, 江欣星, 马燕琳, 孙 菲, 李 崎. 比较人不同细胞来源诱导多能干细胞与胚胎干细胞拟胚体的分化培养过程[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2021, 25(25): 4019-4024. |

| [15] | 周 璨, 杨利楠, 杨 琨, 刘 琪. 诱导多能干细胞基因编辑的应用现状及展望[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2021, 25(25): 4038-4044. |

动物模型建立为研究心脏的发育及遗传性心脏病的发病机制提供一定帮助,但由于物种间的差异巨大,动物模型的研究结果不能完全代表疾病在人体内的发生发展过程,迄今为止,遗传性心脏病的遗传、分子和细胞学发病机制仍未完全阐明[3-4]。现有的研究表明大约有400个基因与遗传性心脏病有关[5],但这不足以完全阐明遗传性心脏病的所有问题。因此,需要新的工具及疾病模型系统来模拟遗传性心脏病患者的遗传背景,从而来阐明心脏异常发育过程中遗传性心脏病发生的病理生理学机制。

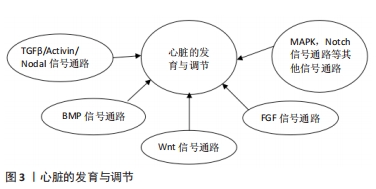

诱导多能干细胞(induced pluripotent stem cell,iPSC)是通过将已经分化的体细胞重新编程而形成的一种具有更多功能的表型、能够自我更新并能分化为所有3个胚层的类胚胎干细胞样细胞,其最早是由日本科学家山仲弥申等于2006年将4种重编程因子(c-Myc、Oct3/4、Sox2、Klf4)导入至小鼠成纤维细胞中形成了类胚胎干细胞样的细胞[6],并于2007年成功将人成纤维细胞诱导分化为iPSC[7]。在其发现不久之后,多项研究表明iPSC定向分化可以产生特定的体细胞,如神经元、造血细胞和心肌细胞(cardiomyocytes,CM)等[8-10]。iPSC的来源广泛,不涉及胚胎干细胞相应的伦理问题,不仅如此,iPSC具有自我更新及多向分化潜能,还具有模拟宿主遗传背景的功能。基于上述这些特性,它为科学家探索疾病发生及发展的病理生理学机制提供了一个全新的平台[11]。目前,iPSC来源细胞已经广泛应用到多种疾病模型的构建,包括许多退行性疾病如帕金森综合征[12]、阿尔茨海默症等[13],在这些疾病研究中iPSC可作为探索发病机制的模型工具,也可成为新药研发的平台,亦可为针对患病个体的细胞替代治疗提供基础。在心血管疾病的研究中,iPSC同样在疾病模型构建、药物开发及细胞替代治疗中具有广泛的应用前景[14]。针对于遗传性心脏疾病的研究,人类诱导多能干细胞(human induced pluripotent stem cell,hiPSC)为研究与遗传性心脏病相关的基因突变和发育途径提供了一个独特的平台。因此,该文章综述目前iPSC在遗传性心脏疾病模型构建中的应用情况,以期为遗传性心脏疾病的发病机制研究提供一定的基础。 中国组织工程研究杂志出版内容重点:干细胞;骨髓干细胞;造血干细胞;脂肪干细胞;肿瘤干细胞;胚胎干细胞;脐带脐血干细胞;干细胞诱导;干细胞分化;组织工程

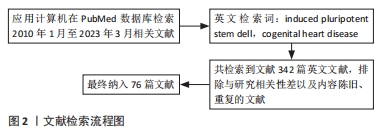

1.1.1 检索人及检索时间 第一作者于2023年1-3月应用计算机进行检索。

1.1.2 检索文献时限 检索时间范围重点为2010年1月至2023年3月,同时纳入少量的远期相关文献与远期经典文献进行综述。

1.1.3 检索数据库 PubMed数据库。

1.1.4 检索词 “induced pluripotent stem cell,congenital heart disease”。

1.1.5 检索文献类型 综述性论文、研究型论文及著作等。

1.1.6 手工检索情况 无。

1.1.7 检索策略 见图1。

1.2 入选标准

1.2.1 纳入标准 通过文章标题以及摘要进行初步筛选,通过精读以及泛读筛选出与研究相关的文献。

1.2.2 排除标准 研究目的及内容与此综述无关的文献以及重复性的研究。

1.3 文献质量评估和数据的提取 共检索到342篇文献,全部为英文文献,排除与研究相关性差以及内容陈旧、重复的文献,纳入76篇符合标准的文献进行综述,见图2。

由于体内复杂的各种调控因素,iPSC-CM不能完全模拟整个心脏的作用,例如药物对心脏的影响可能依赖于肝脏对化合物的代谢激活,而这一特征在细胞培养模型中无法复制,由于体内研究的目的是研究不同系统条件下的复杂相互作用,因此iPSC-CM不能完全替代体内研究。另外,由于iPSC-CM模型的应用在很大程度上仅限于遗传性疾病,特别是那些病理可在单细胞水平上复制的疾病,这种局限性使其很难模拟多种细胞参与的疾病,特别是遗传特异性不强的多类型细胞参与的疾病。

由于转录因子,特别是用于诱导产生iPSC的c-Myc等重编程因子存在致癌的风险,虽然目前研究者们致力于将iPSC应用于一些疾病的治疗或者作为一些干预手段应用于临床,但是iPSC的潜在致癌风险是应用于临床前必须要解决的问题。最后,iPSC分化方案的变化可能会导致分化后的细胞表型不一致、分化的iPSC常常呈现为分化和非分化表型的混杂等问题也依旧是研究者所面临的难题。

3.2 结论与展望 干细胞技术代表着人类生物医学技术的飞速发展,自从1961年人类首次发现多能干细胞以来,无数研究者深耕在这个研究领域。在干细胞技术取得一个又一个突破性进展的同时,人们乐观地认为干细胞技术即将成为人类下一代疾病研究和部分疾病治疗的优选方案,但一个又一个新的问题呈现在研究者的面前,使得干细胞的全面应用仍然需要跨越一个又一个难关。

iPSC技术作为目前干细胞研究领域最为耀眼的明珠,以其具有自我更新能力、多向分化以及避免了如胚胎干细胞的伦理问题等优势成为了研究热点,并且随着CRISPR/Cas9技术、生物材料和3D打印技术等先进技术的进步,iPSC的潜在应用得到了扩展。

虽然目前iPSC存在不能完全模拟体内模型,而且处于不成熟的阶段等不足,但是iPSC-CM在基因功能评估、患者风险分层、药物检测和个性化治疗方面发挥着越来越重要的作用;随着iPSC技术的不断发展,患者特异性iPSC在建立遗传性心脏病疾病模型方面的重要性越来越大,相信在未来利用iPSC技术将进一步有助于对心脏发育过程的研究,特别是基于iPSC建立的类器官模型的出现,将为揭示心脏发育及遗传性心脏病的机制及探寻新的个体化治疗提供强有力的平台。 中国组织工程研究杂志出版内容重点:干细胞;骨髓干细胞;造血干细胞;脂肪干细胞;肿瘤干细胞;胚胎干细胞;脐带脐血干细胞;干细胞诱导;干细胞分化;组织工程

#br#

#br#

文题释义:

诱导多能干细胞:是日本科学家Shinya Yamanaka等将4种重编程因子(c-Myc, Oct3/4,Sox2和 Klf4)导入体细胞产生的具有全能性的干细胞,现在已成为最理想的细胞模型之一。遗传性心脏病:主要指通过基因遗传给下一代所形成的心脏病,如肥厚型心肌病、扩张性心肌病、心律失常等疾病。

中国组织工程研究杂志出版内容重点:干细胞;骨髓干细胞;造血干细胞;脂肪干细胞;肿瘤干细胞;胚胎干细胞;脐带脐血干细胞;干细胞诱导;干细胞分化;组织工程

人类诱导多能干细胞是目前干细胞研究领域的研究热点,研究者们通过人类诱导多能干细胞诱导分化成其他细胞用于研究疾病发病机制或者作为动物模型和原代细胞系的替代品进行药物的临床前研究,并且人类诱导多能干细胞由于其具有人类基因组,所以在分化后能够表达多种人类体细胞的特异性基因。虽然目前人类诱导多能干细胞仍然面临着表型不成熟、可能的致癌风险、分化表型与非分化表型混杂等问题,但已有许多研究者对这些问题发起了挑战,在未来,人类诱导多能干细胞会有更加丰富的应用,会有更多潜在的用途被研究者们开发出来。

中国组织工程研究杂志出版内容重点:干细胞;骨髓干细胞;造血干细胞;脂肪干细胞;肿瘤干细胞;胚胎干细胞;脐带脐血干细胞;干细胞诱导;干细胞分化;组织工程

| 阅读次数 | ||||||

|

全文 |

|

|||||

|

摘要 |

|

|||||