Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research ›› 2022, Vol. 26 ›› Issue (17): 2762-2767.doi: 10.12307/2022.548

Previous Articles Next Articles

Blood flow restriction method for inducing cross-education phenomenon and muscle function reconstruction

Wang Yongchao1, 2, Wang Baochen3, 4, Wei Zhuying5, Bao Chunyu1, 2, Liu Shijun6, Meng Qinghua1

- 1School of Physical Education and Educational Science, 2Tianjin Key Laboratory of Exercise Physiology and Sports Medicine, 3Teaching Experiment and Training Center, 4Tianjin Teaching Experimental Demonstration Center for Physical Training, 5Division of Scientific Research and Postgraduate, 6Department of Competitive Sports, Tianjin University of Sport, Tianjin 301617, China

-

Received:2021-03-24Revised:2021-05-08Accepted:2021-05-26Online:2022-06-18Published:2021-12-27 -

Contact:Bao Chunyu, MD, Professor, School of Physical Education and Educational Science, Tianjin University of Sport, Tianjin 301617, China; Tianjin Key Laboratory of Exercise Physiology and Sports Medicine, Tianjin University of Sport, Tianjin 301617, China -

About author:Wang Yongchao, Master candidate, School of Physical Education and Educational Science, Tianjin University of Sport, Tianjin 301617, China; Tianjin Key Laboratory of Exercise Physiology and Sports Medicine, Tianjin University of Sport, Tianjin 301617, China -

Supported by:the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Nos. 11372223 and 11102135 (to MQH); Key Project of Tianjin Municipal Natural Science Foundation, Nos. 17JCZDJC36000 and 18JCZDJC35900 (to MQH); Tianjin Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project, No. TJTY18-010 (to LSJ); the General Project of Humanities and Social Science Research in Tianjin Colleges and Universities, No. 2019SK091 (to WBC)

CLC Number:

Cite this article

Wang Yongchao, Wang Baochen, Wei Zhuying, Bao Chunyu, Liu Shijun, Meng Qinghua. Blood flow restriction method for inducing cross-education phenomenon and muscle function reconstruction[J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(17): 2762-2767.

share this article

Add to citation manager EndNote|Reference Manager|ProCite|BibTeX|RefWorks

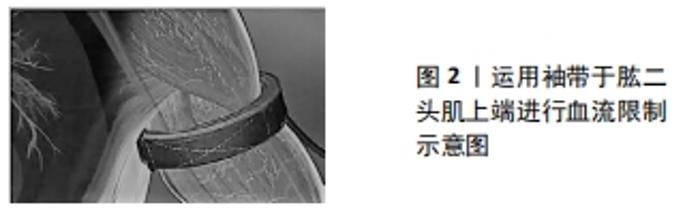

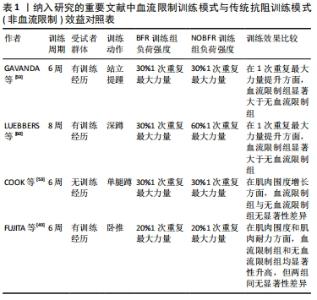

2.1 交叉迁移现象的机制与应用现状 短期单侧的阻力训练不仅会增加目标肌肉的自主收缩力量,同时在另一侧未训练肌肉群中也会表现出一定比例的力量提升,对肢体一侧进行短期运动技能培训同样会导致技能熟练度的交互转移[9-10],人们将这一现象称为交叉迁移现象[11]。此现象自1894年被发现以来,已经有一些实验证实了其存在。在过去的30年里,专家学者们用各种各样的方法来探究交叉迁移现象的确切机制,如使用表面肌电图、外周神经电刺激、经颅磁刺激及功能磁共振成像等[12-18],但不幸的是,到目前为止与交叉迁移相关的神经机制仍难以确定。对于其产生机制,现今得到更多默认的是单侧阻力训练后的交叉迁移现象属于神经源性[19]。并且至少有两种神经机制理论可以部分解释单侧阻力训练后的交叉迁移现象,其中一种是在机体进行抗阻训练时,可能与单侧肌肉收缩反复激活同侧大脑结构有关,这是对同侧脑区适应性的训练刺激,这种机制得到了未训练肢体中皮质脊髓神经元数量增加和皮质内抑制减少的支持[14,20-24]。换句话说,单侧收缩时的交叉激活会导致2个皮质的神经可塑性发生改变[25],以此增加了运动指令产生的输出量,这就解释了未训练肢体的行为增益。第2个潜在机制是单侧阻力训练后大脑半球间通讯的改变,它也可以影响半球的短皮质内抑制回路和长皮质内抑制回路[26],因此,这是目前人们对于交叉迁移现象较能达成的共识解释。 基于交叉迁移现象的独特效应,其很可能适用于某些特定环境,如肌肉骨骼康复的不同阶段、骨科损伤或卒中后患者的早期恢复等[27]。尤其是对于一些肢体损伤后不利于在早期直接进行患侧运动康复,但又迫切需要重新投入使用的运动员而言,能够在损伤康复期间最大程度地保留肢体功能水平并尽快恢复,这样的手段就显得格外重要。例如,前交叉韧带损伤是最为常见的膝关节损伤,主要发生在具有切割和旋转的运动模式中。患有前交叉韧带损伤的个体如果希望恢复到受伤前的运动水平,就需要进行前交叉韧带重建[28-29]。然而,在前交叉韧带重建之后,通常会观察到明显的肌肉力量下降、负荷模式不对称以及膝关节稳定性显著的降低,这可能会导致较低的恢复速度和第2次前交叉韧带损伤[30-32]。因为在前交叉韧带重建早期,股四头肌在非负重位置(伸腿)的强化被认为不利于患处愈合,所以在运动康复过程中,建议这些患者进行膝关节活动受限的负重训练[33]。由此条件下的恢复速度显然无法满足一些迫切需要重返赛场的运动员们的需求,如此看来,利用交叉迁移现象的康复手段似乎更为适宜。对于交叉迁移现象的影响幅度,有1篇2017年的Meta分析研究对此进行了总结[34],在对来自785例受试者的31项研究进行定量分析后,结果显示上肢和下肢的力量增益幅度分别为9.4%和16.4%,且动态的训练方案(向心和离心)比等长训练方案显著增加对侧肌肉力量,增益幅度分别为:离心17.7%,向心15.9%,等长8.2%。 考虑到交叉迁移效应有服务于肌肉骨骼损伤和卒中风险人群的潜力,因此还必须考虑到年龄因素对交叉迁移能力的影响。为了更为清晰地对比不同年龄人群对交叉迁移效果的敏感性,有研究以青年群体和老年群体作为实验对象,各选择14人进行为期4周的单侧膝关节伸展训练,在阻力训练前后对训练和未训练的腿进行最大自主等速和等长测试,通过测试获得不同角速度下的峰值扭矩和加速度增长幅度。最终结果显示在2个不同年龄群体中,通过交叉迁移获得的力量和加速度增益并无显著区别[35],此外,目前针对上半身的实验证据表明,年龄因素并不影响交叉迁移效应的增益幅度[36-38]。而对于经受训练的腿,上述研究结果也支持先前的研究:短期(≤6周)抗阻训练诱发的力量变化在年轻人和老年人之间是相似的。因此总的来说,最近的发现表明年龄并不会削弱交叉迁移的效应幅度。区别于年龄因素的影响,HARPUT等[39]则对个体在训练过程中,肌肉的动态收缩方式与交叉迁移的关系进行了研究。HARPUT等[39]对48例单侧腘绳肌前交叉韧带重建患者进行为期8周、每周3次的健侧等速训练,受试者随机分为3组:向心交叉迁移组、离心交叉迁移组、对照组,在术后的第5周开始训练,直至第12周结束,通过测量第4周(训练前)、第12周(训练后)的最大自愿等速肌力来进行数据对比,最后结果显示:与对照组相比,在术后第12周(干预后),向心交叉迁移组和离心交叉迁移组的股四头肌肌力均提升较大;术后第12周,向心交叉迁移组和离心交叉迁移组股四头肌肌力高于对照组,但两组间无显著性差异。 尽管交叉迁移拥有广泛的临床实用性,在未训练肢体的肌肉力量上也有着显著增益,但仍然拥有较多无法回避的问题。例如,样本量相对较小,并且目前还尚无针对交叉迁移效应的标准化运动训练处方,这使得其在临床应用上仍处于研究、探索阶段。从功能角度上比较直接针对训练和对侧训练时,数据显示在对强侧训练后,未经训练的弱肢的力量改善对运动能力的影响不大。这种训练后功能性改善不明显的一个可能性解释是由于神经机制而非肌肉机制介导的[40-41],尽管目前采用的测量方法可能缺乏敏感性,且没有证明它会影响肌肉的形态和生化特性[42-43];当肌肉通过改变其伸展性和黏弹性等特性来直接影响强化时,这些方面在交叉迁移效应中实际上是缺失的。基于这些考虑,目前如果训练目标是提高成绩而不是力量,则不推荐直接利用交叉迁移效应的训练模式。同时作者建议,只有选定的患者具有严重单侧无力和疲劳,不能充分行使他们较弱的一侧时,可以将其考虑作为第一个选择。在这种情况下,肢体间接获得的肌肉力量增加可以代表一个开始的力量水平,这可能足以维持到随后的直接训练。并且只要一侧肢体不能活动,交叉迁移就可能具有实际意义,而一旦某些功能能力恢复,就可以停止使用间接方法(如约束诱导运动疗法)。尽管交叉迁移有着积极的影响,但单边阻力训练计划在康复环境中相对很少被使用。这源于目前对交叉迁移现象的认识更多处于实验阶段,且实验样本数量相对较少,因此目前也仅能应用于有限的目标群体。所以,加强未来对交叉迁移的深入研究可能有助于提高对其运动处方价值的认识。 2.2 血流限制法的机制与应用 与交叉迁移效应所使用的传统抗阻训练法不同,血流限制法以其独特的训练方式被广泛应用于临床康复人群,也称之为KAATSU训练[44]。血流限制法训练起源于50年前的日本[45],通过在肌肉近端施加充气袖套或松紧带在低负荷强度下进行训练,见图2,以此来获得肌肉力量增长和诱导骨骼肌肥大,负荷强度仅需10%-30% 1次重复最大力量;并且对于无训练经历的人群,这种低负荷强度的训练可以产生与传统高负荷强度相似的力量增长和骨骼肌肥大。但是对于血流限制法训练中激活增加的力量和引发的肌肉肥大机制目前还尚不明确。许多证据涉及到肌肉细胞肿胀反应和代谢产物堆积所导致的间接影响,这可能是由于缺血引起的生化应激反应和在运动中代谢产物的积累使得更多2型肌纤维被招募,后者通过疲劳的方式增加肌肉激活进而提高训练效率。同时代谢的应激反应和组织缺氧促使缺氧诱导因子1α和血管内皮生长因子表达(它们都是血管生成的有利刺激因子)[46-47]。此外,肌纤维肿胀通过mTOR/S6K1介导的哺乳动物靶向途径和卫星细胞向肌纤维迁移方式,以此来促进细胞蛋白质的合成[48-49],这些反应的增强最终导致肌肉肥大和骨骼肌毛细血管增加[50-51]。"

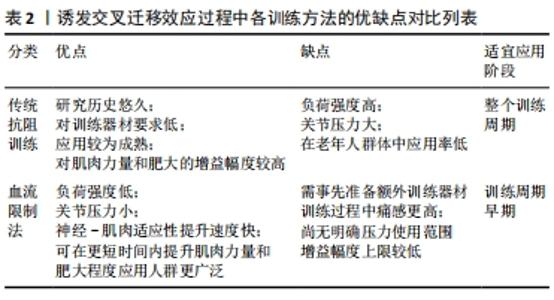

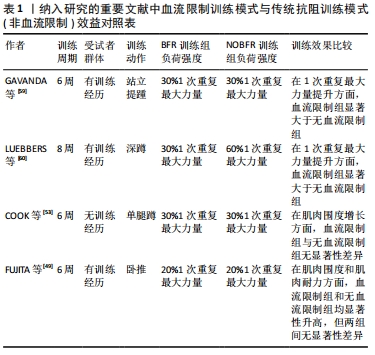

在一篇2020年的Meta分析报告中指出,与没有血流限制法训练的对照组相比,血流限制法训练显著增加了老年人的肌肉力量(1次重复最大力量测试)、肌肉横截面积和身体功能(定时起立和坐立);在力量上的平均增长幅度为2.9%-35.6%,肌肉横截面积平均增长幅度为3.1%-8.0%,在功能测试中的平均增长幅度为12%-28%[52]。同时该报告也指出,虽然血流限制法训练对提高老年人的力量是有效的,但是与没有血流限制法的传统高负荷训练相比,这种增加的效果并不明显,COOK等[53]的实验也证明了这一点。并且在传统力量训练后,健康的或功能受限的老年人身体功能没有得到或仅得到中度改善[54-56],尽管确实观察到了力量的增加[57]。而对于血流限制法训练的安全性,在最近的一次评估肌肉骨骼疾病患者与该方法相关的安全性和不良事件的系统性综述中,血流限制法被评定为是一种安全的训练方法[58]。此外,目前还没有研究报告显示,由于血流限制法训练期间的不适或与训练相关的任何可能的伤害导致的样本丢失,这也同样加强了该方法的安全可行性评估。所以对于那些对传统高负荷训练接受能力较低的老年人和有特殊需求的人而言,血流限制法就显得更为适宜。 血流限制法训练不仅应用于老年群体和运动康复人群,对于有训练经历的健康人群和运动员同样有着积极意义。有研究对30名具有2年以上在健身房训练经历的受试者进行为期6周、每周3次的站立提踵训练,将全部受试者随机分为血流限制法训练组和非血流限制法训练组,在负荷强度和重复组数相同的条件下,两组人员均将训练动作执行至力竭,最终通过受试者的1次重复最大力量和肌肉质量来进行比对[59],结果显示,两组的1次重复最大力量均显著增加(血流限制法,ES=1.80;非血流限制法,ES=2.50),血流限制法组和非血流限制法组的增长幅度分别为24.80%和20.95%;即使仅训练了6周,低负荷强度的血流限制法和非血流限制法同样导致了肌肉质量的改变,两组的相对变化平均值分别为3.29%和1.94%。但在该研究中的一个未知点是,多年的训练经历是否包含对小腿的专门性训练,因为在健身房的训练环境里很少有针对小腿肌群的独特训练,如若没有针对训练,则受试者的训练经历就显得略微苍白。有研究则选取25名青年举重队的男性高中生作为受试者,进行不同训练模式下的深蹲练习[60]。青年运动员们被随机分为传统高负荷,低重复次数组(H组);传统低负荷,高重复次数组(L组)和低负荷,高次数的血流限制法训练组(LB组)。经过8周,每周3次的训练后,测试结果得出:LB组的腿部力量增加显著,而H组和L组的腿部力量没有明显增长;尽管总容积负荷相等,但是L组的深蹲1次重复最大力量表现并没有增加,相反,L组仅仅在6周内维持了他们的试验前强度水平。 众所周知,无论采用何种方法,机械应力都是促进生理适应的重要因素。相比于传统抗阻训练的高负荷、高增益特点,血流限制法训练的低负荷特性无疑更易于被特殊人群所接受,尤其是仅需要恢复一定的身体功能和运动康复人群,如老年人群体。血流限制法训练在老年人中已经被证明是一种有效的增强力量的方法,并且由于在研究中使用了较低的外部负荷而引人注目。同时,不仅是针对健康的人群,对于具有暂时性运动障碍的老年人同样拥有可观的获益,见表1。"

2.3 血流限制法训练特点与交叉迁移结合的可行性分析 现阶段,无论对交叉迁移效应的机制研究有着怎样的疑问,其在临床康复特定人群中都有着无法替代的作用。相比于以往运用传统训练模式来诱发交叉迁移效应,血流限制法的训练模式就更易于执行,且更容易被患者接受。交叉迁移效应的传导路线是由神经系统所承载,强有力的证据支持同侧“未经训练”的大脑半球作为交叉迁移的主要中介[61],尽管具体的皮质通路和适应性神经生理学反应尚未完全明确[41]。但是这些皮质的适应最终都是在运动单位水平实现的。一般来说,肌肉力量上升的早期阶段受到激活运动单元放电特性的强烈影响,而后期阶段则与肌肉的最大强度更加相关[62-64]。血流限制法的训练模式即可以显著增强这种神经-肌肉适应性。但是这种更强大的适应水平能否过度到未训练一侧,亦或是能保留多少,目前还尚未有实验对此进行研究。从受试群体考虑,对于无训练经历,即神经-肌肉适应性提升空间很大的人群而言,血流限制法训练确实会较传统阻力训练更易提升运动单位的招募水平,但就顶级专业运动员而言,这种近乎微小的提升空间似乎就显得无足轻重。如此看来,从神经机制的角度分析,普通人群完全符合血流限制法-交叉迁移的训练机制,并且有着足够大的提升空间。而受伤的运动员们则更适合以此来进行维持和减缓技能水平和肌肉力量下降的速率。从训练方案的角度出发,传统的抗阻训练模式中同样具有可以提升神经-肌肉适应性的运动处方(repetitions to failure with low load,LL-RF)。当个体在以较小的负荷强度(30%1次重复最大力量)进行训练时,在每组动作中重复至力竭(无法完整完成一次规范的动作)同样可以达到血流限制法训练相似的效果,即局部代谢水平增加,运动单位招募能力升高,神经-肌肉适应性增强。两者均应用了较小的负荷强度,但不同点在于LL-RF方案的训练量要远大于血流限制法,且个体痛感较高,无法作为一种长期可执行的训练方案。综合而言,传统的抗阻训练方案是全面发展机体各项素质的基础,当个体需要在某一项进行强化时,只需要将抗阻训练方案的基本要素做出相应调整即可,如训练量、负荷强度、重复次数和动作速度等。在不使用外界帮助的条件下,提高神经控制水平、反应速度等都需要个体进行大量反复练习,由此使得时间成本过高。血流限制法训练则在外部道具的帮助下,以较少的时间和人工成本即可在神经机制上获得较大提升。 在训练的安全性上,与传统阻力训练-交叉迁移的训练模式相比,血流限制法-交叉迁移具有显著的关节压力小,负荷强度低的特点。在相同的局部代谢压力下,血流限制法训练只需要更低的负荷强度和更少的训练量即可达成。这无疑大幅度降低了老年群体受伤的风险,同时也因此获得了广泛的受众人群。同时在现有证据中对血流限制法安全性的系统评估表明,血流限制法与额外的心血管压力或发病率无关[65-68],相反,血流限制法引起的急性和局部高血压反应会导致多种积极的心血管适应,如血管内皮功能的改善,外周血循环以及动静脉顺应性[69]。 相比于血流限制法训练的种种优势,其缺陷也十分突出。到目前为止对血流限制法压力强度的限定还尚无1个界定标准。在众多的文献方案中,反复出现的问题是患者们使用的压力各不相同,所以目前很难得出1个最佳的压力范围。这还需要在未来的实践中不断探索。由于血流限制法的优势在于其神经机制所产生的运动单位招募增加,训练效率提升进而引发的肌肉肥大和力量增长,所以这种肌肉本身强度素质提升较小的训练方法会使得其最终增益幅度有很大限制,当个体在短时间内得到了大幅度提升后,其在之后的训练中将进步缓慢。但也正因为血流限制法训练对神经系统的依赖性,使得它在交叉迁移效应的使用中拥有独特效益。"

| [1] FARTHING JP. Cross-education of strength depends on limb dominance: implications for theory and application. Exercise Sport Sci Rev. 2009;37(4):179-187. [2] MAGNUS CRA, ARNOLD CM, JOHNSTON G, et al. Cross-education for improving strength and mobility after distal radius fractures: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med. 2013;94(7):1247-1255. [3] KIM CY, KIM HD. Effect of crossed-education using a tilt table task-oriented approach in subjects with post-stroke hemiplegia: a randomized controlled trial. J Rehabil Med. 2018;50(9):792-799. [4] KIM CY, LEE JS, KIM HD, et al. The effect of progressive task-oriented training on a supplementary tilt table on lower extremity muscle strength and gait recovery in patients with hemiplegic stroke. Gait Posture. 2015;41(2):425-430. [5] SUN Y, LEDWELL NMH, BOYD LA, et al. Unilateral wrist extension training after stroke improves strength and neural plasticity in both arms. Exp Brain Res. 2018; 236(7):2009-2021. [6] SUZUKI T, BEAN JF, FIELDING RA. Muscle power of the ankle flexors predicts functional performance in community-dwelling older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(9):1161-1167. [7] SPINK MJ, FOTOOHABADI MR, WEE E, et al. Foot and ankle strength, range of motion, posture, and deformity are associated with balance and functional ability in older adults. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(1):68-75. [8] MORELAND JD, RICHARDSON JA, GOLDSMITH CH, et al. Muscle weakness and falls in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(7):1121-1129. [9] PEREZ MA, TANAKA S, WISE SP, et al. Neural substrates of intermanual transfer of a newly acquired motor skill. Curr Biol. 2007;17(21):1896-1902. [10] SCHULZE K, LUDERS E, JANCKE L. Intermanual transfer in a simple motor task. Cortex. 2002;38(5):805-815. [11] GREEN LA, GABRIEL DA. The effect of unilateral training on contralateral limb strength in young, older, and patient populations: a meta-analysis of cross education. Phys Ther Rev. 2018;23(4-5):238-249. [12] CANNON RJ, CAFARELLI E. Neuromuscular adaptations to training. J Appl Physiol. 1987;63(6):2396-2402. [13] CAROLAN B, CAFARELLI E. Adaptations in coactivation after isometric resistance training. J Appl. Physiol. 1992;73(3):911-917. [14] MASON J, FRAZER AK, HORVATH DM, et al. Ipsilateral corticomotor responses are confined to the homologous muscle following cross-education of muscular strength. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2018;43(1):11-22. [15] KIM HE, CORCOS DM, HORNBY TG. Increased spinal reflex excitability is associated with enhanced central activation during voluntary lengthening contractions in human spinal cord injury. J Neurophysiol. 2015;114(1):427-439. [16] GOODWILL AM, KIDGELL DJ. The Effects of whole-Body vibration on the cross-transfer of strength. Sci World J. 2012;112(2):413-425. [17] LEE M, GANDEVIA SC, CARROLL TJ. Unilateral strength training increases voluntary activation of the opposite untrained limb. Clin Neurophysiol. 2009;120(4):802-808. [18] RUDDY KL, LEEMANS A, WOOLLEY DG, et al. Structural and functional cortical connectivity mediating cross education of motor function. J Neurosci. 2017; 37(10):2555-2564. [19] LEE M, CARROLL TJ. Cross education - Possible mechanisms for the contralateral effects of unilateral resistance training. Sports Med. 2007;37(1):1-14. [20] KIDGELL DJ, STOKES MA, PEARCE AJ. Strength training of one limb increases corticomotor excitability projecting to the contralateral homologous limb. Motor Control. 2011;15(2):247-266. [21] COOMBS TA, FRAZER AK, HORVATH DM, et al. Cross-education of wrist extensor strength is not influenced by non-dominant training in right-handers. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2016;116(9):1757-1769. [22] LATELLA C, KIDGELL DJ, PEARCE AJ. Reduction in corticospinal inhibition in the trained and untrained limb following unilateral leg strength training. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2012;112(8):3097-3107. [23] LEUNG M, RANTALAINEN T, TEO WP, et al. The ipsilateral corticospinal responses to cross-education are dependent upon the motor-training intervention. Exp Brain Res. 2018;236(5):1331-1346. [24] ZULT T, GOODALL S, THOMAS K, et al. Mirror training augments the cross-education of strength and affects inhibitory Paths. Med Sci Sports. 2016;48(6):1001-1013. [25] RUDDY KL, CARSON RG. Neural pathways mediating cross education of motor function. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7(1):112-121. [26] PEREZ MA, COHEN LG. Mechanisms underlying functional changes in the primary motor cortex ipsilateral to an active hand. J Neurosci. 2008;28(22):5631-5640. [27] YURDAKUL OV, KILICOGLU MS, REZVANI A, et al. How does cross-education affects muscles of paretic upper extremity in subacute stroke survivors? Neurol Sci. 2020;41(12):3667-3675. [28] BURLAND JP, LEPLEY AS, DISTEFANO LJ, et al. Alterations in physical and neurocognitive wellness across recovery after ACLR: a preliminary look into learned helplessness. Phys Ther Sport. 2019;40:197-207. [29] BURLAND JP, LEPLEY AS, CORMIER M, et al. Examining the relationship between neuroplasticity and learned helplessness after ACLR: early versus late recovery. J Sport Rehabil. 2021;30(1):70-77. [30] ITHURBURN MP, PATERNO MV, FORD KR, et al. Young athletes with quadriceps femoris strength asymmetry at return to sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction demonstrate asymmetric single-leg drop-landing mechanics. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(11):2727-2737. [31] PATERNO MV, SCHMITT LC, FORD KR, et al. Biomechanical measures during landing and postural stability predict second anterior cruciate ligament injury after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and return to sport. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(10):1968-1978. [32] SCHMITT LC, PATERNO MV, FORD KR, et al. Strength ssymmetry and landing mechanics at return to sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Med Sci Sports Exercise. 2015;47(7):1426-1434. [33] ESCAMILLA RF, MACLEOD TD, WILK KE, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament strain and tensile forces for weight-bearing and non-weight-bearing exercises: a guide to exercise selection. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012;42(3):208-220. [34] MANCA A, DRAGONE D, DVIR Z, et al. Cross-education of muscular strength following unilateral resistance training:a meta-analysis. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2017; 117(11):2335-2354. [35] HESTER G M, MAGRINI MA, COLQUHOUN RJ, et al. Cross-education: effects of age on rapid and maximal voluntary contractile characteristics in males. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2019;119(6):1313-1322. [36] BEMBEN MG, MURPHY RE. Age related neural adaptation following short term resistance training in women. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2001;41(3):291-299. [37] EHSANI F, NODEHI-MOGHADAM A, GHANDALI H, et al. The comparison of cross-education effect in young and elderly females from unilateral training of the elbow flexors. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2014;28(2):138-138. [38] HUGHES MA, MYERS BS, SCHENKMAN ML. The role of strength in rising from a chair in the functionally impaired elderly. J Biomech. 1996;29(12):1509-1513. [39] HARPUT G, ULUSOY B, YILDIZ T I, et al. Cross-education improves quadriceps strength recovery after ACL reconstruction: a randomized controlled trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27(1):68-75. [40] CARROLL TJ, HERBERT RD, MUNN J, et al. Contralateral effects of unilateral strength training: evidence and possible mechanisms. J Appl Physiol. 2006;101(5):1514-1522. [41] MANCA A, HORTOBAGYI T, ROTHWELL J, et al. Neurophysiological adaptations in the untrained side in conjunction with cross-education of muscle strength: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Appl Physiol. 2018;124(6):1502-1518. [42] PLOUTZ LL, TESCH PA, BIRO RL, et al. Effect of resistance training on muscle use during exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1994;76(4):1675-1681. [43] ENOKA RM. Neural adaptations with chronic physical activity. J Biomech. 1997; 30(5):447-455. [44] SATO, Y. The history and future of KAATSU Training. Int J Kaatsu Training Res. 2005;1(1):1-5. [45] BITTAR ST, PFEIFFER PS, SANTOS HH, et al. Effects of blood flow restriction exercises on bone metabolism: a systematic review. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2018;38(6):930-935. [46] AMELN H, GUSTAFSSON T, SUNDBERG CJ, et al. Physiological activation of hypoxia inducible factor-1 in human skeletal muscle. FASEB J. 2005;19(8):1009-1011. [47] RICHARDSON RS, WAGNER H, MUDALIAR SRD, et al. Human VEGF gene expression in skeletal muscle: effect of acute normoxic and hypoxic exercise. Am J Physiol. 1999;277(6):H2247-H2252. [48] FRY CS, GLYNN EL, DRUMMOND MJ, et al. Blood flow restriction exercise stimulates mTORC1 signaling and muscle protein synthesis in older men. J Appl Physiol. 2010;108(5):1199-1209. [49] FUJITA S, ABE T, DRUMMOND MJ, et al. Blood flow restriction during low-intensity resistance exercise increases S6K1 phosphorylation and muscle protein synthesis (vol 103, pg 903, 2007). J Appl Physiol. 2008;104(4):1256-1256. [50] ABE T, YASUDA T, MIDORIKAWA T, et al. Skeletal muscle size and circulating IGF-1 are increased after two weeks of twice daily “KAATSU” resistance training. Int J Kaatsu Training Res. 2005;1(1):6-12. [51] YASUDA T, ABE T, SATO Y, et al. Muscle fiber cross-sectional area is increased after two weeks of twice daily KAATSU-resistance training. Int J Kaatsu Training Res. 2005;1(2):65-70. [52] BATISTA MM, SILVA DSGD, BENTO PCB. Effects of blood flow restriction training on strength, muscle mass and physical function in older individuals -systematic review and meta-analysis. Aust Occup Ther J. 2020;(5):1-18. [53] COOK SB, LAROCHE DP, VILLA MR, et al. Blood flow restricted resistance training in older adults at risk of mobility limitations. Exp Gerontol. 2017;99:138-145. [54] SKELTON DA, YOUNG A, GREIG CA, et al. Effects of resistance training on strength, power, and selected functional abilities of women aged 75 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43(10):1081-1087. [55] VASCONCELOS KSS, DIAS JMD, ARAUJO MC, et al. Effects of a progressive resistance exercise program with high-speed component on the physical function of older women with sarcopenic obesity: a randomized controlled trial. Braz J Phys Ther. 2016;20(5):432-440. [56] SAETERBAKKEN AH, BARDSTU HB, BRUDESETH A, et al. Effects of strength training on muscle properties, physical function, and physical activity among frail older people: a pilot study. J Aging Res. 2018;20(2):291-302. [57] LATHAM NK, BENNETT DA, STRETTON CM, et al. Systematic review of progressive resistance strength training in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004; 59(1):48-61. [58] MINNITI MC, STATKEVICH AP, KELLY RL, et al. The safety of blood flow restriction training as a therapeutic intervention for patients with musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review. Am J Sports Med. 2020;48(7):1773-1785. [59] GAVANDA S, ISENMANN E, SCHLOEDER Y, et al. Low-intensity blood flow restriction calf muscle training leads to similar functional and structural adaptations than conventional low-load strength training: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2020;15(6):212-222. [60] LUEBBERS PE, WITTE EV, OSHEL JQ. The effects of practical blood flow restriction training on adolescent lower body strength. J Strength Cond Res. 2017;10(2):211-212. [61] LEE M, HINDER MR, GANDEVIA SC, et al. The ipsilateral motor cortex contributes to cross-limb transfer of performance gains after ballistic motor practice. J Physiol. 2010;588(1):201-212. [62] AAGAARD P, SIMONSEN EB, ANDERSEN JL, et al. Increased rate of force development and neural drive of human skeletal muscle following resistance training. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93(4):1318-1326. [63] MAFFIULETTI NA, AAGAARD P, BLAZEVICH AJ, et al. Rate of force development: physiological and methodological considerations. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2016;116(6): 1091-1116. [64] ANDERSEN LL, AAGAARD P. Influence of maximal muscle strength and intrinsic muscle contractile properties on contractile rate of force development. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2006;96(1):46-52. [65] CLARK BC, MANINI TM, HOFFMAN RL, et al. Relative safety of 4 weeks of blood flow-restricted resistance exercise in young, healthy adults. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2011;21(5):653-662. [66] HEITKAMP HC. Training with blood flow restriction. Mechanisms, gain in strength and safety. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2015;55(5):446-456. [67] LOENNEKE JP, WILSON JM, WILSON GJ, et al. Potential safety issues with blood flow restriction training. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2011;21(4):510-518. [68] PATTERSON SD, HUGHES L, WARMINGTON S, et al. Blood flow restriction exercise position stand:considerations of methodology, application, and safety. Front Physiol. 2019;10(2):114-125. [69] SHIMIZU R, HOTTA K, YAMAMOTO S, et al. Low-intensity resistance training with blood flow restriction improves vascular endothelial function and peripheral blood circulation in healthy elderly people. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2016;116(4):749-757. |

| [1] | Zhu Chan, Han Xuke, Yao Chengjiao, Zhou Qian, Zhang Qiang, Chen Qiu. Human salivary components and osteoporosis/osteopenia [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(9): 1439-1444. |

| [2] | Jin Tao, Liu Lin, Zhu Xiaoyan, Shi Yucong, Niu Jianxiong, Zhang Tongtong, Wu Shujin, Yang Qingshan. Osteoarthritis and mitochondrial abnormalities [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(9): 1452-1458. |

| [3] | Zhang Lichuang, Xu Hao, Ma Yinghui, Xiong Mengting, Han Haihui, Bao Jiamin, Zhai Weitao, Liang Qianqian. Mechanism and prospects of regulating lymphatic reflux function in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(9): 1459-1466. |

| [4] | Gu Zhengqiu, Xu Fei, Wei Jia, Zou Yongdi, Wang Xiaolu, Li Yongming. Exploratory study on talk test as a measure of intensity in blood flow restriction training [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(8): 1154-1159. |

| [5] | Wang Jing, Xiong Shan, Cao Jin, Feng Linwei, Wang Xin. Role and mechanism of interleukin-3 in bone metabolism [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(8): 1260-1265. |

| [6] | Zhu Chan, Han Xuke, Yao Chengjiao, Zhang Qiang, Liu Jing, Shao Ming. Acupuncture for Parkinson’s disease: an insight into the action mechanism in animal experiments [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(8): 1272-1277. |

| [7] | Wu Min, Zhang Yeting, Wang Lu, Wang Junwei, Jin Yu, Shan Jixin, Bai Bingyi, Yuan Qiongjia. Effect of concurrent training sequences on body composition and hormone response: a Meta-analysis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(8): 1305-1312. |

| [8] | An Weizheng, He Xiao, Ren Shuai, Liu Jianyu. Potential of muscle-derived stem cells in peripheral nerve regeneration [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(7): 1130-1136. |

| [9] | Fan Yiming, Liu Fangyu, Zhang Hongyu, Li Shuai, Wang Yansong. Serial questions about endogenous neural stem cell response in the ependymal zone after spinal cord injury [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(7): 1137-1142. |

| [10] | Guo Jia, Ding Qionghua, Liu Ze, Lü Siyi, Zhou Quancheng, Gao Yuhua, Bai Chunyu. Biological characteristics and immunoregulation of exosomes derived from mesenchymal stem cells [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(7): 1093-1101. |

| [11] | Wu Weiyue, Guo Xiaodong, Bao Chongyun. Application of engineered exosomes in bone repair and regeneration [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(7): 1102-1106. |

| [12] | Zhou Hongqin, Wu Dandan, Yang Kun, Liu Qi. Exosomes that deliver specific miRNAs can regulate osteogenesis and promote angiogenesis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(7): 1107-1112. |

| [13] | Zhang Jinglin, Leng Min, Zhu Boheng, Wang Hong. Mechanism and application of stem cell-derived exosomes in promoting diabetic wound healing [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(7): 1113-1118. |

| [14] | Huang Chenwei, Fei Yankang, Zhu Mengmei, Li Penghao, Yu Bing. Important role of glutathione in stemness and regulation of stem cells [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(7): 1119-1124. |

| [15] | Hui Xiaoshan, Bai Jing, Zhou Siyuan, Wang Jie, Zhang Jinsheng, He Qingyong, Meng Peipei. Theoretical mechanism of traditional Chinese medicine theory on stem cell induced differentiation [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(7): 1125-1129. |

| Viewed | ||||||

|

Full text |

|

|||||

|

Abstract |

|

|||||