Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research ›› 2017, Vol. 21 ›› Issue (19): 3088-3094.doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-4344.2017.19.021

Previous Articles Next Articles

Advance in the diagnosis and treatment of infection after total knee arthroplasty

Zhang Yao, Xu Zhe, Lv Hao, Feng Wei

- Department of Bone and Joint, the First Bethune Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun 130021, Jilin Province, China

-

Online:2017-07-08Published:2017-08-10 -

Contact:Feng Wei, Associate professor, Associate chief physician, Master’s supervisor, Department of Bone and Joint, the First Bethune Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun 130021, Jilin Province, China -

About author:Zhang Yao, Studying for master’s degree, Department of Bone and Joint, the First Bethune Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun 130021, Jilin Province, China -

Supported by:the Project of Science and Technology Department of Jilin University, No. 20160101131JC; the Research Program of Health and Family Planning Commission of Jilin Province, No. 2015Z031

CLC Number:

Cite this article

Zhang Yao, Xu Zhe, Lv Hao, Feng Wei. Advance in the diagnosis and treatment of infection after total knee arthroplasty[J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2017, 21(19): 3088-3094.

share this article

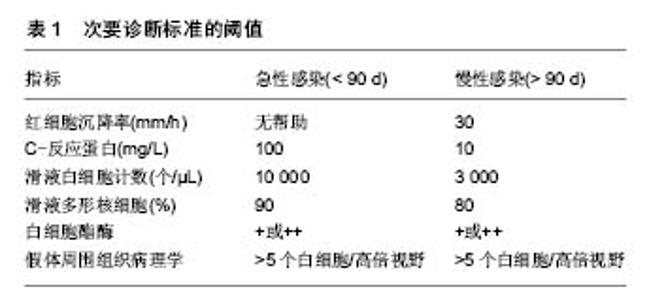

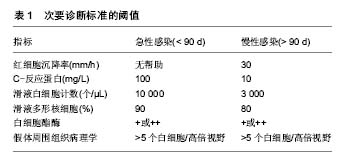

2.1 假体周围感染的危险因素 2.1.1 术前危险因素 患者术前的身体状态与其术后假体周围感染的发生率息息相关,容易导致术后假体周围感染的危险因素主要包括患者营养不良、低蛋白血症、肥胖、患有糖尿病、类风湿性关节炎、创伤性关节炎、行关节腔注射、合并心脏病、贫血、甲状腺疾病、肺部疾病等。由于营养不良导致的身体状态差、免疫功能低下,往往造成更高的术后感染率。Nelson等[6]发现,与营养状态正常的患者相比,低营养状态的患者术后发生浅表感染的概率升高约2倍,深部感染的发生率上升了约3倍。接受全膝关节置换的患者约有27%存在不同程度的低蛋白血症,其程度与年龄呈正相关(> 60)岁。围术期应给予鸡蛋、肉类等高蛋白饮食,必要时输注白蛋白,以提高白蛋白水平,能够降低术后感染发生的风险[7]。多项研究表明,肥胖(体质量指数≥ 35 kg/m2)和患有糖尿病都是全膝关节置换术后发生感染的危险因素[8-12]。肥胖是造成术后假体周围感染的危险因素之一,有研究发现肥胖患者即使在关节置换术前进行减重也并不会明显降低术后感染的发生[13-15]。与骨关节炎患者相比,类风湿性关节炎患者关节置换术后发生感染的风险显著增加[16-19]。创伤性关节炎患者行全膝关节置换后罹患感染的可能性也会增高[20-22]。行关节置换术的患者年龄一般较大,往往合并一些其他系统的疾病,如贫血、心脏疾病、甲状腺疾病、呼吸系统疾病等,这些都是术后发生感染的危险因素[23-26]。除上述危险因数外,Meehan等[27]分析发现,年龄低于50岁的患者较年长患者术后更容易发生假体周围感染,他们认为其原因可能是与老年患者相比,年轻患者往往因继发性关节炎而接受全膝关节置换,但造成年轻患者全膝关节置换术后较年长患者更容易罹患感染的确切原因尚不明确。也有学者的研究表明男性患者较女性患者发生假体周围感染的可能性更大[28-30],其可能的原因是皮肤菌落定殖存在性别差异,这可能与皮肤pH,皮脂产生或皮肤厚度的性别差异有关[31-32]。患者患有抑郁症也会增加术后感染的概率。既往行翻修术会增加假体周围感染的可能,但没有证据表明其他关节手术史会增加术后感染的风险[12]。关节腔内注射激素被认为是一种安全的治疗方法,但类固醇药物使用史会增加患者术后感染的可能,这也是类风湿性关节炎患者术后易发生假体周围感染的原因之一[12,33-34]。关节腔穿刺一定要无菌操作的前提下进行,不规范的关节腔穿刺会显著增加感染的风险,很多患者入院前有过在基层医疗机构进行关节腔穿刺抽液或注射药物的情况,若未在严格无菌操作下进行,将增加其术后假体周围感染的可能。 2.1.2 术中危险因素 手术过程中易导致术后感染的危险因素主要包括不规范的无菌操作、手术时间较长。手术时间越长越增加术野被污染的可能,以及随着手术时间延长,造成出血量增加、术后患者状态差等,都增加了患者术后发生感染的可能性[24,28-30]。因此,术中应严格无菌操作,应在百级层流手术室进行手术,严格消毒与铺巾,尽量缩短手术时间,减少手术创伤。手术过程中应反复冲洗术野。还要注意控制手术参观人数,避免不必要的人员走动[7]。另外,有医生在行初次全膝关节置换时为预防感染会在骨水泥中加入一些抗生素,但抗生素骨水泥的应用对预防初次关节置换术后的假体周围感染的效果并不确切,而且骨水泥中加入的抗生素会带来诸如药物过敏,非感染状态下的药物毒性,细菌耐药及影响骨水泥的机械性能等问题[35-36]。对于需要行双膝置换的患者,有文献报道同时行双侧膝关节置换发生感染的风险要高于双侧分期置换[37],有研究认为同时行双侧膝关节置换术要优于分次手术[38-39]。也有研究认为同时或分次行双侧膝关节置换术后发生感染的可能性并无差异[40]。但大部分关于该问题的研究都存在样本量过少,患者分组缺乏统一入选标准等局限性,因此,对于需要行双膝置换的患者选择同时或分次手术还需临床医生根据患者的自身情况综合考虑。 2.1.3 术后危险因素 术后可能导致假体周围感染的危险因素包括留置导尿管及伤口引流管的时间过长、异体输血、口腔、泌尿系感染等。留置导尿管会升高尿路感染的发生率从而增加假体周围感染的可能。有研究表明,留置导尿管发生泌尿系感染的概率与未留置导尿管相比显著升高[41]。中国髋、膝关节置换术加速康复专家共识不推荐常规安置尿管。对于手术时间长、术中出血量多、同期双侧全膝关节置换的患者,其术后发生尿潴留的风险高,应安置尿管预防尿潴留,但不应超过24 h。该共识推荐安置尿管指征:①手术时间>1.5 h,手术失血超过5%或>300 mL;②同期双侧全膝或全髋关节置换。不安置尿管指征:手术时间短,术中出血少[7]。术后是否留置引流管目前尚存在争议,有文献表明是否留置引流管对术后感染的影响并不大[42-44]。然而,也有研究表明留置引流管会增加逆行感染的风险[45]。中国髋、膝关节置换术加速康复专家共识认为安置引流管指征为:①严重关节畸形矫正者;②创面渗血明显。并应于出血趋于停止(引流管无明显出血或引流管血清分离)时尽早拔除引流管。对采用微创操作技术及关节囊内操作,无严重畸形矫正和出血少的患者不建议使用引流管[7]。术后异体输血也是导致假体周围感染的危险因素,Frisch等[46]研究发现,异体输血患者术后发生深部感染的概率是2.4%,而未输血患者发生深部感染的概率仅为0.5%。因此,全膝关节置换患者围手术期要注意贫血的诊断及治疗,并尽可能减少术中失血,以降低患者的输血需求。中国髋、膝关节置换加速康复—围术期贫血诊治专家共识推荐全膝关节置换患者围术期贫血的治疗起始值为血红蛋白:男性<130 g/L,女性<120 g/L[47]。虽然异体输血是导致假体周围感染的危险因素之一,但有文献报道自体血回输并不会增加近期感染的可能[48]。另外,局部使用氨甲环酸也是一种较为安全的可有效减少手术出血的有效方法,从而减少术后输血的概率[49]。凝血酶作为止血剂应用能显著降低术后出血量及血红蛋白下降程度,且不会升高术后感染及深静脉血栓形成的风险[50]。术后如发生口腔、泌尿系感染,会增加假体周围血源性感染的风险,因此,术前就应排除皮肤、口腔黏膜破损、感染等问题。 2.2 假体周围感染的早期诊断 假体周围感染是导致全膝关节置换 术后翻修的主要原因,延长了患者的住院周期,增大了患者的致残率和死亡率,耗费大量财力及医疗资源[51]。如果感染控制不理想可发展为截肢甚至威胁患者生命,其结果往往是灾难性的。因此,临床工作中,若能做到早发现早治疗,将会对感染的控制带来极大的帮助。假体周围感染的早期诊断主要包括以下几个方面。 2.2.1 初步评估 首先要根据患者的具体情况如术后切口是否持续渗液,体温、皮温变化等对患者发生感染的可能性进行危险程度划分,这需要详细了解患者病史及临床资料,进行详细的体格检查[52]。 2.2.2 实验室检查 包括红细胞沉降率、超敏C-反应蛋白、血白细胞计数及分类等。红细胞沉降率、C-反应蛋白对诊断假体周围感染具有重要意义,它们的重要性要大于血白细胞,当红细胞沉降率和C-反应蛋白均异常时,应高度怀疑感染,但要注意区分其他会引起红细胞沉降率、C-反应蛋白升高的情况,如类风湿性关节炎,身体其他系统存在炎症以及术后正常的红细胞沉降率、C-反应蛋白升高。红细胞沉降率、C-反应蛋白结果均正常则感染可能性不大。另外,红细胞沉降率正常对排除假体周围感染要比红细胞沉降率增快对确诊假体周围感染要更有意义[52]。在红细胞沉降率和/或C-反应蛋白水平异常时,应行关节腔穿刺术[52-53]。穿刺抽取的关节液要进行微生物培养、白细胞计数及其分类比例。在关节腔穿刺的过程中,应严格的无菌操作,若滑液中中性粒细胞比率>65%或白细胞计数> 1.7×109 L-1,表明极有可能存在慢性感染[52]。若微生物培养结果与考虑感染的可能性不相符,应再次穿刺抽液做培养。由于患者往往近期使用过抗生素,临床上很多患者的培养结果为阴性,因此建议患者在行关节腔穿刺液培养之前,应停用抗生素2周以上,在获得培养结果之前,不建议使用抗生素[52-53]。白细胞介素6被认为是诊断假体周围感染的最敏感的血清实验室检查,但由于其检测费用高、检测不方便等原因,目前在临床上应用范围较小[21,54]。 2.2.3 影像学检查 X射线片可以发现假体周围松动或有透亮区,美国骨科医师学会(AAOS)的一项研究发现CT对假体周围感染的确诊有帮助,但对排除感染作用的不大[52]。对于怀疑假体周围感染的患者,也可行核成像检查,如标记白细胞成像与骨或骨髓成像,F-18氟脱氧葡萄糖-正电子发射断层扫描(FDG-PET)成像,镓成像或标记白细胞成像等[52]。 2.2.4 组织学检查 对于怀疑假体周围感染的但未能确诊而接受再次手术的患者,术中应取假体周围组织做冷冻切片行病理学检查,并取假体周围组织做多次细菌培养[52]。术中冰冻切片应取假体周围至少3块组织送检,阳性结果为每个高倍视野出现多于5个白细胞[55]。 2.3 假体周围感染的诊断标准 根据假体周围感染国际专家小组的共识[55],对假体周围感染诊断包括以下2条主要诊断标准和5条次要诊断标准: 主要诊断标准:①窦道直接与假体相通;②假体周围组织或关节液培养获得病原菌。 次要诊断标准:①红细胞沉降率、C-反应蛋白升高;②滑液白细胞计数升高,或白细胞酯酶检测阳性;③滑液中多形核细胞计数升高;④假体周围组织学分析阳性;⑤假体周围组织或关节液培养阳性,见表1。 临床上符合以上主要诊断标准的其中1项,或者符合次要诊断标准的其中3项,即可诊断为假体周围感染。该诊断标准同时强调,临床上未达以上诊断标准的患者也可能存在感染,特别是对那些因低毒性致病菌导致感染的患者而言。"

2.4 假体周围感染的分型 根据感染出现的时间和持续的时间可将全膝关节置换术后假体周围感染分为4种类型[56-57]。Ⅰ型:无症状型感染,患者没有感染的症状,只是在翻修手术所取组织中培养出细菌,且至少在2份不同位置标本中培养出相同细菌,此类患者由于未出现感染症状,生活质量一般不受影响,但易较早出现假体松动;Ⅱ型:早期术后感染,在初次关节置换术后4周内出现感染症状,此类感染多为医源性感染,致病菌以金黄色葡萄球菌和葡萄球菌多见;Ⅲ型:急性血源性感染,患者在关节置换术后有功能恢复良好,但出现急性感染表现,此型感染多为假体置换术后细菌血源性种植引起,感染症状较典型;Ⅳ型:慢性感染,感染症状出现在关节置换术后超1个月,或急性血源性感染病程迁延超过4周的感染。 2.5 假体周围感染的治疗 在进行治疗前需要考虑以下问题:感染为哪种类型、是表浅感染还是深部感染、感染的发生距离置换术后有多长时间、患者自身对感染有哪些影响因素、膝关节周围软组织条件如何,尤其是伸膝装置的完整性、假体是否松动、病原学检查是否支持感染、是否有足够的内科治疗支持以及患者的期望值和功能要求等,再根据具体情况决定治疗方案。治疗目标是清除感染,缓解疼痛,保留肢体功能。治疗方案包括以下5种。 2.5.1 单纯抗生素治疗 适用于合并严重的全身情况不能耐受任何手术或低毒性细菌感且假体没有松动的患者。单纯抗生素治疗一般不能彻底清除深部感染,有效率仅为18%-24%[58-59]。 2.5.2 清创保留假体 Ⅱ型或Ⅲ型感染可考虑清创保留假体。适应证为2周内的急性感染、对抗生素敏感的革兰阳性菌感染、无术后伤口长期渗液或窦道形成、影像学无假体松动或感染[57]。瑞典膝关节注册中心对145例全膝关节置换术后感染的患者采用了清创保留假体的治疗方案,其成功率为75%。该研究发现假体周围组织细菌培养显示,感染的致病菌以金黄色葡萄球菌最常见,约占37%,凝固酶阴性葡萄球菌约占23%,并发现感染病原学类型不影响治疗结果,在金葡菌感染患者在抗生素治疗方面,没有联合应用利福平组治疗失败率明显高于抗生素连用利福平组[60-61]。Koh等[61]回顾分析了52例全膝关节置换术后感染患者,清创保留假体总的成功率71%。其中术后早期感染组成功率为82%,急性血源性感染组成功率为55%,同时也发现手术的成功率与手术的及时性相关,与感染分型和细菌类型无关。但Kim等[62]的研究认为,耐药性革兰阳性球菌感染是影响清创保留假体术成功率的因素之一。目前认为清创保留假体手术成功的关键点在于手术清创应及早进行,对金黄色葡萄球菌感染的患者清创术更应及早进行,感染症状出现48 h以后再行清创术将显著降低手术成功 率[57]。术中需彻底清创,彻底清除失活的组织和异物,彻底切除关节滑膜和其他炎性组织。术中使用双氧水和碘伏反复浸泡,大量生理盐水冲洗,更换聚乙烯垫片,术中应取活检送病理并做细菌培养。术后根据药敏结果选择抗生素,术后静脉注射抗生素至少4-6周,然后应评估是否还需要继续口服抗生素[57]。 2.5.3 人工膝关节翻修术 适用于Ⅳ型感染,即持续1个月以上的慢性感染适合行翻修术,禁忌证包括:持续性或复发性感染、膝关节周围软组织覆盖差,伸膝装置破坏。采用一期翻修还是二期翻修仍存在争议,目前临床较常采用二期翻修术[63-66]。但也有文献报道一期翻修术的效果要优于二期翻修[67-68]。但由于目前的研究大多存在样本数量少、随访时间短、入选标准不严格等问题,采用一期翻修还是二期翻修还需要大样本、多中心的进一步研究[69]。 一期翻修的优势在于只需进行一次手术、住院时间短、抗生素使用周期短、费用低、骨量丢失少、恢复快、患者满意度高等[68]。Zahar等[69]对行一期翻修的70例假体周围感染患者进行了平均10年的随访,其感染控制率为93%。Haddad等[68]对102例全膝关节置换术后慢性感染随访至少3年,其中28例(27%)一期翻修术后感染复发率0,而74例(73%)行二期翻修的患者感染复发率6.7%。但一期翻修的缺点在于清创技术要求高、有不能彻底清除感染的隐患。 二期翻修目前被认为是临床治疗慢性全膝关节置换术后感染的最有效的治疗手段[63-64]。标准的二期翻修步骤为取出假体和骨水泥,彻底清创,含抗生素的骨水泥spacer维持关节间隙,敏感抗生素静点4-6周后复查红细胞沉降率、C-反应蛋白水平在正常范围内且关节穿刺液细菌培养阴性后置入新的人工假体,见图1。Haleem等[63]对96例全膝关节置换术后感染行二期翻修术的患者进行了平均7.2年的随访,假体的5年生存率为93.5%,10年生存率为85%。 2.5.4 关节融合术 主要适用于翻修术后仍持续存在的顽固感染,伸膝装置坏、周围软组织覆盖差,免疫功能抑制,感染细菌毒力强,对传统抗生素耐药,患者功能要求低,多个关节类风湿性关节炎的患者,关节融合术常用的固定方式有外固定架固定、双钢板固定、髓内针固定,见图2。关节融合术作为全膝关节置换失败的补救措施,具有缓解疼痛、稳定关节、下肢负重良好的优点,是感染晚期导致的全膝关节置换术后严重的症状和功能障碍首选方法。 2.5.5 截肢术 是治疗全膝关节置换术后感染的最后手段。主要用于顽固性疼痛,大量骨缺,软组织缺失,多次翻修手术失败,全身感染或有生命危险的患者。"

| [1] Arden NK, Leyland KM. Osteoarthritis year 2013 in review: clinical. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21(10): 1409-1413.[2] Dziedzic KS, Healey EL, Porcheret M, et al. Implementing the NICE osteoarthritis guidelines: a mixed methods study and cluster randomised trial of a model osteoarthritis consultation in primary care--the Management of OsteoArthritis In Consultations (MOSAICS) study protocol. Implement Sci. 2014;9: 95.[3] Gbejuade HO, Lovering AM, Webb JC. The role of microbial biofilms in prosthetic joint infections. Acta Orthop. 2015;86(2): 147-158.[4] Mortazavi SM, Molligan J, Austin MS, et al, Parvizi J. Failure following revision total knee arthroplasty: infection is the major cause. Int Orthop. 2011;35(8): 1157-1164.[5] Patel A, Pavlou G, Mújica-Mota RE, et al. The epidemiology of revision total knee and hip arthroplasty in England and Wales: a comparative analysis with projections for the United States. A study using the National Joint Registry dataset. Bone Joint J. 2015;97-B(8): 1076-1081.[6] Nelson CL, Elkassabany NM, Kamath AF, et al. Low Albumin Levels, More Than Morbid Obesity, Are Associated With Complications After TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015; 473(10): 3163-3172.[7] 周宗科,翁习生,曲铁兵,等. 中国髋、膝关节置换术加速康复——围术期管理策略专家共识[J]. 中华骨与关节外科杂志, 2016, 9(1):1-9.[8] Jämsen E, Nevalainen P, Eskelinen A, et al. Obesity, diabetes, and preoperative hyperglycemia as predictors of periprosthetic joint infection: a single-center analysis of 7181 primary hip and knee replacements for osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(14): e101.[9] Hwang JS, Kim SJ, Bamne AB, et al. Do glycemic markers predict occurrence of complications after total knee arthroplasty in patients with diabetes. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(5): 1726-1731.[10] Dowsey MM, Choong PF. Obese diabetic patients are at substantial risk for deep infection after primary TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(6): 1577-1581.[11] Watts CD, Wagner ER, Houdek MT, et al. Morbid Obesity: Increased Risk of Failure After Aseptic Revision TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(8): 2621-2627.[12] Kunutsor SK, Whitehouse MR, Blom AW, et al. Patient-Related Risk Factors for Periprosthetic Joint Infection after Total Joint Arthroplasty: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(3): e0150866.[13] Smith TO, Aboelmagd T, Hing CB, et al. Does bariatric surgery prior to total hip or knee arthroplasty reduce post-operative complications and improve clinical outcomes for obese patients? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Bone Joint J. 2016;98-B(9): 1160-1166.[14] Martin JR, Watts CD, Taunton MJ. Bariatric surgery does not improve outcomes in patients undergoing primary total knee arthroplasty. Bone Joint J. 2015;97-B(11): 1501-1505.[15] Lui M, Jones CA, Westby MD. Effect of non-surgical, non-pharmacological weight loss interventions in patients who are obese prior to hip and knee arthroplasty surgery: a rapid review. Syst Rev. 2015; 4: 121.[16] Ravi B, Croxford R, Hollands S, et al. Increased risk of complications following total joint arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(2): 254-263.[17] LoVerde ZJ, Mandl LA, Johnson BK, et al. Rheumatoid Arthritis Does Not Increase Risk of Short-term Adverse Events after Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Retrospective Case-control Study. J Rheumatol. 2015;42(7): 1123-1130.[18] Kadota Y, Nishida K, Hashizume K, et al. Risk factors for surgical site infection and delayed wound healing after orthopedic surgery in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Mod Rheumatol. 2016. 26(1): 68-74.[19] Ravi B, Escott B, Shah PS, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing complications following total joint arthroplasty for rheumatoid arthritis versus for osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(12): 3839-3849.[20] Bala A, Penrose CT, Seyler TM, et al. Outcomes after Total Knee Arthroplasty for post-traumatic arthritis. Knee. 2015; 22(6): 630-639.[21] Frangiamore SJ, Siqueira MB, Saleh A, et al. Synovial Cytokines and the MSIS Criteria Are Not Useful for Determining Infection Resolution After Periprosthetic Joint Infection Explantation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474(7): 1630-1639.[22] Saleh H, Yu S, Vigdorchik J, et al. Total knee arthroplasty for treatment of post-traumatic arthritis: Systematic review. World J Orthop. 2016;7(9): 584-591.[23] Peersman G, Laskin R, Davis J, et al. Infection in total knee replacement: a retrospective review of 6489 total knee replacements. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;(392): 15-23.[24] Pulido L, Ghanem E, Joshi A, et al. Periprosthetic joint infection: the incidence, timing, and predisposing factors. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(7): 1710-1715.[25] Poultsides LA, Ma Y, Della VAG, et al. In-hospital surgical site infections after primary hip and knee arthroplasty-- incidence and risk factors. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(3): 385-389.[26] Lee QJ, Mak WP, Wong YC. Risk factors for periprosthetic joint infection in total knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2015;23(3): 282-286.[27] Meehan JP, Danielsen B, Kim SH, et al. Younger age is associated with a higher risk of early periprosthetic joint infection and aseptic mechanical failure after total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(7): 529-535.[28] Namba RS, Inacio MC, Paxton EW. Risk factors associated with deep surgical site infections after primary total knee arthroplasty: an analysis of 56,216 knees. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(9): 775-782.[29] Willis-Owen CA, Konyves A, Martin DK. Factors affecting the incidence of infection in hip and knee replacement: an analysis of 5277 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(8): 1128-1133.[30] Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Lau E, et al. Prosthetic joint infection risk after TKA in the Medicare population. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(1): 52-56.[31] Fierer N, Hamady M, Lauber CL, et al. The influence of sex, handedness, and washing on the diversity of hand surface bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(46): 17994-17999.[32] Kim MK, Patel RA, Shinn AH, et al. Evaluation of gender difference in skin type and pH. J Dermatol Sci. 2006;41(2): 153-156.[33] Chaiyakit P, Meknavin S, Pakawattana V. Results of peri-articular steroid injection in the treatment of chronic extra-articular pain after total knee arthroplasty. J Med Assoc Thai. 2012;95 Suppl 10: S48-52.[34] Horne G, Devane P, Davidson A, et al. The influence of steroid injections on the incidence of infection following total knee arthroplasty. N Z Med J. 2008;121(1268): U2896.[35] Zhou Y, Li L, Zhou Q, et al. Lack of efficacy of prophylactic application of antibiotic-loaded bone cement for prevention of infection in primary total knee arthroplasty: results of a meta-analysis. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2015;16(2): 183-187.[36] Schiavone PA, Corona K, Giulianelli M, et al. Antibiotic-loaded bone cement reduces risk of infections in primary total knee arthroplasty? A systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016 .[37] Del PJL, Patel R. Clinical practice. Infection associated with prosthetic joints. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(8): 787-794.[38] Spicer E, Thomas GR, Rumble EJ. Comparison of the major intraoperative and postoperative complications between unilateral and sequential bilateral total knee arthroplasty in a high-volume community hospital. Can J Surg. 2013;56(5): 311-317.[39] Poultsides LA, Memtsoudis SG, Vasilakakos T, et al. Infection following simultaneous bilateral total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(8 Suppl): 92-95.[40] Sheth DS, Cafri G, Paxton EW, et al. Bilateral Simultaneous vs Staged Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Comparison of Complications and Mortality. J Arthroplasty. 2016; 31(9 Suppl): 212-216.[41] Huang Z, Ma J, Shen B, et al. General anesthesia: to catheterize or not? A prospective randomized controlled study of patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(3): 502-506.[42] Li N, Liu M, Wang D, et al. Comparison of complications in one-stage bilateral total knee arthroplasty with and without drainage. J Orthop Surg Res. 2015;10: 3.[43] Liu XH, Fu PL, Wang SY, et al. The effect of drainage tube on bleeding and prognosis after total knee arthroplasty: a prospective cohort study. J Orthop Surg Res. 2014; 9: 27.[44] Zhang X, Li G, Ma J, et al. [A meta-analysis for the efficacy and safety of drainage after primary total knee arthroplasty]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2014;94(29): 2282-2285.[45] Fan Y, Liu Y, Lin J, et al. Drainage does not promote post-operative rehabilitation after bilateral total knee arthroplasties compared with nondrainage. Chin Med Sci J. 2013;28(4): 206-210.[46] Frisch NB, Wessell NM, Charters MA, et al. Predictors and complications of blood transfusion in total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(9 Suppl): 189-192.[47] 周宗科, 翁习生, 向兵,等. 中国髋、膝关节置换术加速康复--围术期贫血诊治专家共识[J]. 中华骨与关节外科杂志, 2016, 9(1): 10-15.[48] Ku?era B, Náhlík D, Hart R, et al. [Post-operative retransfusion and intra-operative autotransfusion systems in total knee arthroplasty. A comparison of their efficacy]. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech. 2012;79(4): 361-366.[49] Chimento GF, Huff T, Ochsner JL, et al. An evaluation of the use of topical tranexamic acid in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(8 Suppl): 74-77.[50] Wang C, Han Z, Zhang T, et al. The efficacy of a thrombin-based hemostatic agent in primary total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res. 2014; 9: 90.[51] Bozic KJ, Kurtz SM, Lau E, et al. The epidemiology of revision total knee arthroplasty in the United States. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(1): 45-51.[52] Della VC, Parvizi J, Bauer TW, et al. Diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infections of the hip and knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010; 18(12): 760-770.[53] Parvizi J, Della VCJ. AAOS Clinical Practice Guideline: diagnosis and treatment of periprosthetic joint infections of the hip and knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18(12): 771-772.[54] Ahmad SS, Becker R, Chen AF, et al. EKA survey: diagnosis of prosthetic knee joint infection. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016; 24(10): 3050-3055.[55] Parvizi J, Gehrke T. Definition of periprosthetic joint infection. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(7):1331.[56] Tsukayama DT, Goldberg VM, Kyle R. Diagnosis and management of infection after total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A Suppl 1: S75-80.[57] Leone JM, Hanssen AD. Management of infection at the site of a total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005; 87(10): 2335-2348.[58] Bengston S, Knutson K, Lidgren L. Treatment of infected knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;(245): 173-178.[59] Hanssen AD, Rand JA. Evaluation and treatment of infection at the site of a total hip or knee arthroplasty. Instr Course Lect. 1999;48: 111-122.[60] Holmberg A, Thórhallsdóttir VG, Robertsson O, et al. 75% success rate after open debridement, exchange of tibial insert, and antibiotics in knee prosthetic joint infections. Acta Orthop. 2015;86(4): 457-462.[61] Koh IJ, Han SB, In Y, et al. Open debridement and prosthesis retention is a viable treatment option for acute periprosthetic joint infection after total knee arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2015;135(6): 847-855.[62] Kim JG, Bae JH, Lee SY, et al. The parameters affecting the success of irrigation and debridement with component retention in the treatment of acutely infected total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Surg. 2015;7(1): 69-76.[63] Haleem AA, Berry DJ, Hanssen AD. Mid-term to long-term followup of two-stage reimplantation for infected total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;(428): 35-39.[64] Jämsen E, Stogiannidis I, Malmivaara A, et al. Outcome of prosthesis exchange for infected knee arthroplasty: the effect of treatment approach. Acta Orthop. 2009;80(1): 67-77.[65] Leone JM, Hanssen AD. Management of infection at the site of a total knee arthroplasty. Instr Course Lect. 2006;55: 449-461.[66] Silvestre A, Almeida F, Renovell P, et al. Revision of infected total knee arthroplasty: two-stage reimplantation using an antibiotic-impregnated static spacer. Clin Orthop Surg. 2013; 5(3): 180-187.[67] Nagra NS, Hamilton TW, Ganatra S, et al. One-stage versus two-stage exchange arthroplasty for infected total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24(10): 3106-3114.[68] Haddad FS, Sukeik M, Alazzawi S. Is single-stage revision according to a strict protocol effective in treatment of chronic knee arthroplasty infections. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015; 473(1): 8-14.[69] Zahar A, Kendoff DO, Klatte TO, et al. Can Good Infection Control Be Obtained in One-stage Exchange of the Infected TKA to a Rotating Hinge Design? 10-year Results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474(1): 81-87. |

| [1] | Wang Jianping, Zhang Xiaohui, Yu Jinwei, Wei Shaoliang, Zhang Xinmin, Xu Xingxin, Qu Haijun. Application of knee joint motion analysis in machanism based on three-dimensional image registration and coordinate transformation [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(在线): 1-5. |

| [2] | Zhuang Zhikun, Wu Rongkai, Lin Hanghui, Gong Zhibing, Zhang Qianjin, Wei Qiushi, Zhang Qingwen, Wu Zhaoke. Application of stable and enhanced lined hip joint system in total hip arthroplasty in elderly patients with femoral neck fractures complicated with hemiplegia [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(9): 1429-1433. |

| [3] | Zhang Lichuang, Xu Hao, Ma Yinghui, Xiong Mengting, Han Haihui, Bao Jiamin, Zhai Weitao, Liang Qianqian. Mechanism and prospects of regulating lymphatic reflux function in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(9): 1459-1466. |

| [4] | Zhang Jichao, Dong Yuefu, Mou Zhifang, Zhang Zhen, Li Bingyan, Xu Xiangjun, Li Jiayi, Ren Meng, Dong Wanpeng. Finite element analysis of biomechanical changes in the osteoarthritis knee joint in different gait flexion angles [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(9): 1357-1361. |

| [5] | Yao Xiaoling, Peng Jiancheng, Xu Yuerong, Yang Zhidong, Zhang Shuncong. Variable-angle zero-notch anterior interbody fusion system in the treatment of cervical spondylotic myelopathy: 30-month follow-up [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(9): 1377-1382. |

| [6] | Wu Bingshuang, Wang Zhi, Tang Yi, Tang Xiaoyu, Li Qi. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: from enthesis to tendon-to-bone healing [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(8): 1293-1298. |

| [7] | An Weizheng, He Xiao, Ren Shuai, Liu Jianyu. Potential of muscle-derived stem cells in peripheral nerve regeneration [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(7): 1130-1136. |

| [8] | Zhang Jinglin, Leng Min, Zhu Boheng, Wang Hong. Mechanism and application of stem cell-derived exosomes in promoting diabetic wound healing [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(7): 1113-1118. |

| [9] | Liu Dongcheng, Zhao Jijun, Zhou Zihong, Wu Zhaofeng, Yu Yinghao, Chen Yuhao, Feng Dehong. Comparison of different reference methods for force line correction in open wedge high tibial osteotomy [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(6): 827-831. |

| [10] | Shao Yangyang, Zhang Junxia, Jiang Meijiao, Liu Zelong, Gao Kun, Yu Shuhan. Kinematics characteristics of lower limb joints of young men running wearing knee pads [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(6): 832-837. |

| [11] | Huang Hao, Hong Song, Wa Qingde. Finite element analysis of the effect of femoral component rotation on patellofemoral joint contact pressure in total knee arthroplasty [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(6): 848-852. |

| [12] | Yuan Jing, Sun Xiaohu, Chen Hui, Qiao Yongjie, Wang Lixin. Digital measurement and analysis of the distal femur in adults with secondary knee valgus deformity [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(6): 881-885. |

| [13] | Zhou Jianguo, Liu Shiwei, Yuan Changhong, Bi Shengrong, Yang Guoping, Hu Weiquan, Liu Hui, Qian Rui. Total knee arthroplasty with posterior cruciate ligament retaining prosthesis in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis with knee valgus deformity [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(6): 892-897. |

| [14] | Yang Yang, Li Naxi, Zhang Jian, Wang Mian, Gong Taifang, Gu Liuwei. Effect of tourniquet combined with exsanguination band use on short-term lower extremity venous thrombosis after knee arthroscopy [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(6): 898-903. |

| [15] | Yang Kuangyang, Wang Changbing. MRI evaluation of graft maturity and knee function after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with autogenous bone-patellar tendon-bone and quadriceps tendon [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(6): 963-968. |

| Viewed | ||||||

|

Full text |

|

|||||

|

Abstract |

|

|||||