Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research ›› 2017, Vol. 21 ›› Issue (15): 2424-2431.doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-4344.2017.15.023

Previous Articles Next Articles

Type ll odontoid fractures in the elderly: surgical or conservative method?

Du Shi-yao, Ni Bin

- Department of Orthopedics, Shanghai Changzheng Hospital Affiliated to the Second Military Medical University, Shanghai 200003, China

-

Online:2017-05-28Published:2017-06-07 -

Contact:Ni Bin, Department of Orthopedics, Shanghai Changzheng Hospital Affiliated to the Second Military Medical University, Shanghai 200003, China -

About author:Du Shi-yao, Master, Physician, Department of Orthopedics, Shanghai Changzheng Hospital Affiliated to the Second Military Medical University, Shanghai 200003, China -

Supported by:the General Project of National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 81472127

CLC Number:

Cite this article

Du Shi-yao, Ni Bin. Type ll odontoid fractures in the elderly: surgical or conservative method?[J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2017, 21(15): 2424-2431.

share this article

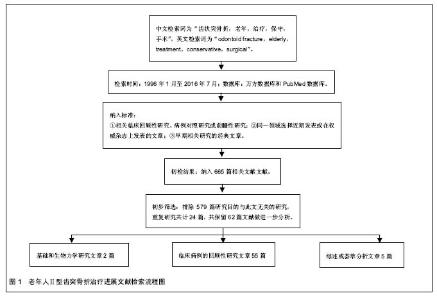

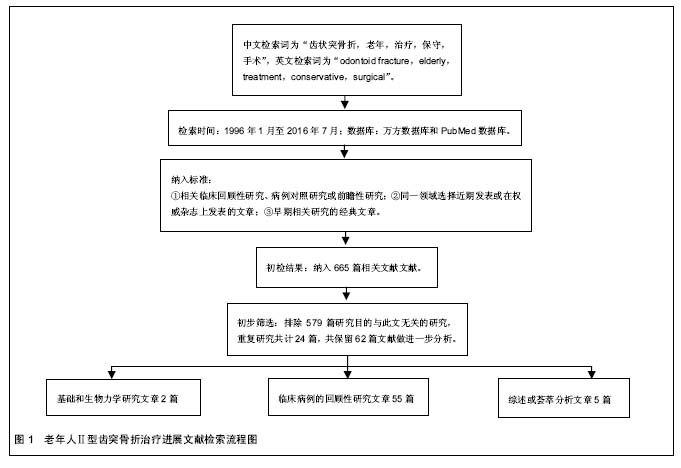

2.2 病因学及分型 尽管齿状突骨折在各个年龄段均有发生,但年轻患者常在交通事故时发生,而老年人常在低能量损伤(摔伤或跌落)后造成,并且神经功能损伤更严重[5-6]。生物力学实验证实Ⅱ型齿突骨折源于侧屈和过伸的作用力[7]。枢椎椎管由于代偿性间隙较大通常可以避免神经功能损伤[8],但是一旦出现脊髓损伤,后果常常是致命的。 目前最为公认的齿突骨折分型是Anderson和 D’Alonzo分型。1974年,Anderson等[9]提出了一套基于骨折形态的齿突骨折分类系统。Ⅰ型,骨折位于齿突尖部、横韧带之上,是一种稳定性骨折;Ⅱ型,位于齿突基部、横韧带与枢椎体交界处,是最常见的骨折类型,具有不稳定性;Ⅲ型,骨折延伸至枢椎椎体,大部分为稳定性骨折,除非有明显的骨折移位。尽管这套分类系统应用最为广泛,但是仍存在一些不足。比如,某些低位的Ⅱ型骨折和高位的Ⅲ型骨折难以区分,另外未对骨折线方向、移位及粉碎性程度详细描述,从而影响后续治疗方案的制订。针对前者,Hadley等[10]提出一种亚分型ⅡA型,将其定义为齿状突基底部骨折、骨折端后下方有一较大块的游离骨块,为不稳定性骨折。针对后者问题,Grauer等[11]提出了一种具有治疗指导意义的Ⅱ型齿突骨折亚型分型系统,该系统基于骨折线方向、移位及粉碎程度将Ⅱ型骨折进一步分为ⅡA、ⅡB及ⅡC型。ⅡA型定义为无移位或移位不多,及无粉碎性骨折,此型骨折适于外固定制动;ⅡB型定义为骨折有移位,骨折线由前上斜向后下或横向,此型骨折如果复位良好且无骨质疏松适于前路齿突螺钉固定;ⅡC型骨折骨折线由前下斜向后上,或者有明显的粉碎性骨折,此型适于后路寰枢椎固定。作者文中采用的是Anderson和D’Alonzo分型。 骨折分型系统必须满足许多用途的需求,包括用于制订手术方案,预期长远疗效及科学研究。目前存在较多争议,一部分脊柱外科医师认为该分型系统未能考虑临床相关因素,比如骨密度、生理年龄(而非实际年龄)、合并症等,而这些因素可能会影响治疗方案的选择。 2.3 治疗方式的选择 老年患者的治疗相对特殊,当为Ⅱ型齿突骨折的老年人的选择最佳治疗方案时,需要加以考虑几个因素,包括合并伤、合并症、骨折愈合潜力、halo支架或手术的忍受度以及病患的期望值等。由于手术干预和长期的颈椎外固定保守治疗都存在一定的风险,因此对于这类患者的治疗方案目前仍存有很大争议。 尽管既往有文献报道,单独应用外固定治疗、前路齿突螺钉或者后路寰枢椎固定治疗均可以取得一定疗效。然而,大部分临床医生常常倾向于采用多种治疗方法联合应用。影像学上的骨性愈合常常为判断某种治疗方案成功与否的标准[12]。但是,也有些学者认为对于大于65岁的老年患者,判断标准应为稳定的纤维性愈合,并且无临床症状[13]。本文拟针对Ⅱ型齿状突骨折老年患者的治疗方法及相应的临床疗效进行综述报道。 2.3.1 保守治疗 硬颈托被公认是治疗老年人Ⅱ型齿状突骨折的有效方法。很多学者认为年轻患者和老年患者的治疗目标完全不同[14],对于老年患者来说,骨性愈合并非总是必要的,很多学者认为,稳定性纤维愈合对于老年齿状突骨折患者来说,或许也是可以接受的结 果[2,12,15],而硬颈托就可以提供足够的外固定支持。Ryan等[14]报道了29例年龄超过60岁的老年患者通过颈托和halo支架治疗的Ⅱ型齿突骨折病例,尽管有77%的骨折不愈合率,但在随访过程中没有证据显示出现远期神经功能的减退。他们认为,过于强调老年患者的骨性完全愈合和针对非愈合骨折需采用坚强内固定的想法,除非在极个别情况下,否则是值得商榷的。学者们发现骨折不愈合很少会引发脊髓病,并且对于老年患者来说,治疗结果的好坏并不取决于影像学骨折愈合的标准,而是取决于疼痛缓解、生活自理。Muller等[12]报道了通过硬颈托治疗平均年龄在59.1岁的19例患者,骨折愈合率达77%,如果无临床症状的稳定性纤维性愈合被认为是良好的治疗结局,那么成功率可以达到92%。他们认为在影像学结果和临床结局中找不到任何关联,因此可以认为齿突骨折不愈合可能是稳定的,没有临床症状的,而并不代表是差的临床结局。Joestl等[16]回顾性研究了44例平均年龄超过65岁的齿突骨折患者,其中16例采用手术治疗,28例采用halo支具保守治疗,结果显示手术治疗组有14例患者达到满意的疗效,而尽管保守治疗组有26例患者齿突骨折处形成假关节,但最终所有患者均达到满意的临床结局,作者认为寰枢椎融合术适用于齿突不稳定骨折,合并神经症状或者存在持续性疼痛的患者。 Halo支架首次被Perry[17]和Nickel用于治疗小儿麻痹症,在过去的几十年中,经历了一些设计和材料的改良,使其适应证得以拓展。目前halo支架在限制上颈椎活动方面优于其他颈椎矫形器。Koller等[18]通过体外生物力学实验证实,费城颈托和halo支具在限制寰枢椎屈伸活动方面差异并没有显著性意义。Polin等[19]在临床研究中也发现,使用halo支架和费城颈托治疗齿突骨折,二者在远期临床疗效方面差异无显著性意义,尽管前者的骨愈合率较高(47% vs. 26%)。 Horn等[20]首次报道了年龄超过70岁的患者使用halo支架的相关并发症,并发症率和病死率达52%和19%。Tashjian等[21]回顾了78例年龄超过65岁(平均80.7岁)的齿突骨折患者,其中50例Ⅱ型齿突骨折患者,治疗方式分别采取halo支架(38例)、颈托(27例)和手术(13例),采用halo支架治疗的与非halo支架治疗患者的损伤严重程度评分(injury severity score,ISS)无明显差异,而二者发病率及死亡率分别为42%,66%和20%,36%。Patel等[22]报道了54例老年患者通过保守疗法治疗齿突Ⅱ型和Ⅲ型骨折的疗效,结果证实,患者可以通过halo支具和佩戴颈托达到良好的骨性愈合和较高的纤维性愈合,术后功能恢复良好,然而其中有6例患者分别死于支气管肺炎及心血管疾病。 Majercik等[23]甚至认为halo支架的使用对于老年人来说简直就是“宣判死刑”。他们回顾性研究了使用halo支架治疗颈椎损伤的老年患者,骨折类型尚未提及。他们基于相似的ISS和合并症将患者分成2组,再基于年龄分成2个亚组:老年人组129例(年龄>66岁)及年轻组289例(年龄<66岁),研究发现颈椎外伤的老年组患者死亡率约是年轻组的4倍(21% vs. 5%),另外,佩戴halo支具的老年患者的死亡率远高于年轻患者(40% vs. 2%,P < 0.01),而采取手术治疗及佩戴颈托的老年患者死亡率分别是6%和12%。但是Van Middendorp等[24]学者的回顾性研究发现佩戴halo支架的老年患者其死亡率(8%)和肺炎发病率(4%)并不高。Winkler等[25]回顾性研究了 2 847例齿突骨折的老年患者分别进行保守治疗及手术治疗的效果,研究发现手术治疗相关并发症的发生率较前者高,包括肺炎(10.1% vs. 5.9%,P < 0.001)、急性呼吸窘迫综合征(6.0% vs. 2.3%,P < 0.001)、压疮(4.8% vs. 1.3%,P < 0.001),而二者总体住院死亡率并无明显差别(13% vs. 10.3%,P=0.120)。近期2项Meta分析研究均证实,对于Ⅱ型齿突骨折的老年患者,手术治疗的死亡率较保守治疗低[26-27]。 2.3.2 手术治疗 后路寰枢椎融合术:由于halo支具治疗所带来的高并发症率和病死率难以让人接受,学者们提出早期采取内固定治疗Ⅱ型齿突骨折的老年患者[28-29]。对于老年患者,特别是那些合并有其他疾病的Ⅱ型齿突骨折患者,尽管手术治疗后长期存活的可能更大,但脊柱医师仍然经常采用保守治疗策略[30]。而采用保守治疗无效后通过后路手术方案补救的报道目前仅见于年轻患者当中[31]。对于老年患者而言,保守治疗与非保守治疗的相关死亡率和失败率都随着Ⅱ型齿状突骨折患者年龄的增大而增加[32]。根据全美神经外科医师协会和神经外科医师大会(the American Association of Neurological Surgeons and the Congress of Neurological Surgeons)最新指南,如果Ⅱ型齿突骨折具备手术指征,前路或后路寰枢椎内固定融合术均可采用[33]。但是手术路径的选择取决于患者的临床和影像学特点。在过去的几十年里,从Gallie首次提出寰枢椎钛缆固定到Magerl提出的经关节螺钉技术,再到近几年由Goel首次报道的后由Harms和Melcher改良的C1侧块螺钉联合C2椎弓根螺钉,寰枢椎后路内固定技术迅猛发展。在众多外科治疗方法中,后路寰枢椎内固定技术受到最广泛的认可。后路钛缆技术治疗齿突Ⅱ型骨折的骨愈合率已经达到80%-100%[2],相比之下,非手术治疗的骨愈合率报道为23%-82%[12]。目前很多脊柱外科医生将手术治疗手段与halo支架联合应用。经关节螺钉技术比钛缆技术能够提供更加稳定的支持,前者的愈合率接近100%,但是,该技术也有一定局限,如必须良好复位、难以应用于胸椎后凸者;在高达20%的患者中可能因横突孔不完整而不能应用[34];这项技术操作难度大、难以掌握,并且存在伤及椎动脉、脊髓、舌下神经等结构的风险[22]。一项meta分析显示,Magerl技术融合率可达94.6%,神经损伤的发生率为0.2%,椎动脉损伤率为3.1%,螺钉误置的发生率可达7.1%[35]。Goel在1994年描述了C1侧块螺钉联合C2椎弓根螺钉技术,随后2001年Harms和Melcher报道了使用万向螺钉和钛棒的改良技术,因固定效果好、并发症少而迅速流行,成为目前的主流术式,国内外学者都曾在此技术的基础上提出改良方案。Harms技术中,C1侧块螺钉进钉点选择在C1后弓至C1侧块后下部中点连线的中间,方向为垂直或略内收,应用此技术可保留C2神经节。但术中静脉丛大量出血和术后C2神经功能障碍仍是主要并发症。而且Currier[36]和Ebraheim等[37]认为如果C1侧块螺钉的置钉过程中,侧块下壁破裂,有可能损伤颈内动脉和舌下神经。C1椎弓根螺钉于2002年由学者报道,事实上是一种界于寰椎后弓与侧块间的固定螺钉。优点在于抗拔出力更强、能有效避免术中出血和C2神经根激惹。在众多置钉技术中,谭明生教授所介绍的方法成功率最高(92%),Tan等[38]提出将C1后弓作为进针点,从而可以避免Goel技术螺钉穿过C1后弓尾端所造成的静脉丛的损伤。需注意的是,因为寰椎解剖结构的多变性,没有任何一种技术是绝对安全的。一般认为,C1椎弓根高度大于4 mm是应用本技术的前提。但来自西安红会医院的研究人员也发现,当C1椎弓根存在髓腔时,即使其高度小于 4 mm也有可能置入3.5 mm 螺钉。这种技术的骨愈合率与Magerl经关节螺钉技术不相上下,C2椎弓根螺钉进针点相对靠上靠内,因此前者的神经血管损伤风险相对较 小[39]。Wright于2004年首次报道了C2椎板螺钉,内固定螺钉交叉于C2椎板,置钉后可与各种C1内固定物连接,各项生物力学性能均好于峡部螺钉,操作相对简单而椎动脉损伤风险小,多被用来作为C2椎弓根置钉失败或存在高跨椎动脉时的补救方案,近期的研究表明此技术的临床应用效果较好。目前关于后路融合术治疗老年患者齿状突骨折的报道很少,主要包括小样本研究或者特殊的治疗方法或手术技巧。关于颈后路手术和非手术治疗老年齿状突骨折的一项系统回顾和惟一的多中心前瞻性研究表明手术治疗在临床效果[27,40],30 d生存率和长期生存率方面优于保守治疗,尤其是年龄65-84岁的患者。Vaccaro等[40]报道齿突骨折老年患者手术治疗的1年死亡率为14%,低于非手术治疗的26%(P=0.06)。尽管Vaccaro等的研究发现手术治疗可以促使生存改善,但Ⅱ型齿状突骨折老年的1年总死亡率仍然较大。但在术前与患者及其家属交代手术风险及术后提供相应咨询意见时,高死亡率这一信息或许可以提供相应帮助,并且有益于医院和其他审查机构对治疗方案及预后进行总体风险评估。Robinson等[27]认为,接受手术治疗的Ⅱ型齿突骨折老年患者死亡的相对危险度较非手术治疗下降。与这些研究结果相一致,Ryang等[41]在其采用颈后路手术治疗年龄大于80岁的齿突骨折患者的研究中发现,患者术前颈部疼痛的患者术后均有好转,没有新的神经血管损伤或神经功能障碍的恶化,无住院期间发生死亡,30 d死亡率低(6%)。手术的优点是直接减少疼痛,并术后第1天达到即刻固定。此外,术后患者无需佩戴颈托或其他支具,避免发生外固定相关的并发症,例如吸入性肺炎、吞咽困难或者和皮肤刺激、溃疡及感染。 前路齿突螺钉固定术:尽管颈后路固定手术技术成熟,术后可以获得即刻的稳定性,治疗相关死亡率,临床结果总体满意。不幸的是,后路固定技术限制了颈椎旋转活动的将近50%[42],由此推动了另一项替代技术的发展,即Bohler[43]首次提出的前路齿突螺钉固定技术。前路直接的齿突螺钉固定及后路寰枢椎融合两种手术方式治疗齿突骨折均可以提供良好的稳定和融合率。但相比之下,后路寰枢椎融合术需要剥离大量的软组织,而且术中患者长期处于俯卧位,而且老年患者常常存在一些身体状况和解剖条件的限制,据此前路优势就更明显。目前对于老年Ⅱ型齿突骨折患者,特别是不稳定型骨折,前路齿突螺钉技术由于其有效性及安全性得到广泛认可[44],这项技术能够提供颈椎术后即刻的稳定性,保留正常的寰枢椎旋转活动度,并且骨愈合率很高,不需要联合halo支具治疗。许多脊柱外科医生坚信,这项技术作为Ⅱ型齿突骨折老年患者的治疗方案可以达到最完美的解剖和功能结果。在整体人群中,前路齿突螺钉固定的融合率既往文献报道为73%和100%之 间[30,45-46]。但是,在老年患者亚组的临床报道中,骨愈合及并发症方面存在较大差异。Andersson等[47]报道了11例老年齿突骨折患者采用前路齿突螺钉固定后,8例患者出现了严重并发症及假关节的形成。而另外采用后路寰枢椎融合术的7例患者术后临床疗效满意,融合率高。他们据此认为,前路螺钉内固定治疗齿突骨折老年患者临床疗效差。有学者们担忧齿突螺钉技术对于骨质疏松的老年患者是否适用[48]。骨量减少、骨质疏松患者骨愈合能力差、年龄过高及麻醉风险相对较高,这些因素导致齿突螺钉技术在老年患者人群当中的高失败 率[47]。为了避免由于骨质疏松造成潜在的螺钉松动,Etter等[49]采用齿突螺钉联合前路寰枢椎经关节螺钉固定治疗Ⅱ型齿突骨折老年患者,这种手术方式与常规的后路经关节Magerl螺钉相比,仰卧位和较少软组织剥离是其主要的优势所在,而在此之前,有研究也采用前路寰枢椎经关节螺钉固定作为齿突螺钉置钉失败的补救措施,术后临床疗效满意,骨折愈合。还有一些学者认为,骨质疏松症主要是网状骨质疾病,由于前路齿突螺钉内固定的强度主要依赖于齿突远端的高密度皮质骨,因此骨质疏松症可能不会明显地影响螺钉的强度[43]。近期的一项前瞻性研究中,Waschke等[46]通过骨水泥加固的齿突螺钉治疗11例齿突骨折的老年骨质疏松的患者,术后随访发现骨折复位良好,无并发症及翻修病例出现,并且没有骨水泥泄漏,证实这项技术既安全又有效。对于老年患者,特别是那些合并有其他疾病的Ⅱ型齿突骨折患者,尽管手术治疗后长期存活的可能更大,但脊柱医师仍然经常采用保守治疗策略[30]。据此,采用保守治疗无效后通过后路手术方案补救的报道目前仅见于年轻患者当中[31]。然而,保守治疗与非保守治疗的相关死亡率和失败率都随着Ⅱ型齿状突骨折患者年龄的增大而增加[32]。Osti等[50]分析了老年患者Ⅱ型齿状突骨折前路螺钉内固定术的失败原因。他们发现内固定失败与患者的年龄以及寰齿关节退行性改变严重程度之间有显著的关联。通常,在正常群体中寰齿关节退行性改变的发生率在72岁时退变42%,在80岁时退变达61%。Lakshmanan等[51]发现寰齿关节炎发生的平均年龄是79岁,而Ⅱ型齿状突骨折的老年患者,其寰齿关节炎的发生率增加90%。作者推测,齿状突的尖端由于退变保持相对静止,这样,因摔伤产生的高转速压力可能会在枢椎椎体及齿状突的连接处形成非典型高应力,从而导致Ⅱ型齿状突骨折。并且这种压力可能会在严重寰齿关节炎患者的齿突螺钉固定区域持续存在。这或许可以解释在老年患者人群前路齿突螺钉固定的高失败率。单枚或双枚齿突螺钉的应用目前仍存在争议,Dailey等[52]将骨折愈合定义为骨性愈合、纤维性愈合及不愈合,基于此标准,结果显示双枚螺钉的稳定性优于单枚螺钉,二者的骨折愈合率分别为96%和56%,也有文献报道二者在远期生物力学稳定性及融合率方面均无明显差异[53]。 由于老年颈椎病患者通常合并有心、肺等其他器官功能的减退,颈椎术区除了颈髓、脊神经,还分布有大量神经节,老年患者通常对于疼痛的耐受性较强,因此手术全身麻醉相对于局部麻醉的风险相应会增加[54]。但全身麻醉对于维持老年患者术中的生命体征平稳和处理术中突发情况有其优势,并且近年来麻醉技术的重大进步使得老年患者全身麻醉的风险显著降低[55]。 微创手术:老年患者对于传统开放手术的耐受性较差,近年来,上颈椎经皮内固定术式逐渐兴起,克服了传统开放手术的缺点,特别对于机体功能减退、基础疾病多、体质较差的老年人尤为适合。池永龙等[56]回顾性研究了45例上颈椎损伤的老年患者,术后微创和开放手术组的患者目测类比评分、JOA评分较术前均有明显改善,但微创手术时间短、出血量少,并且术后下地时间明显早于开放手术的患者。相比开放手术,经皮微创手术具有创伤小、出血少、恢复快等优点,但是也存在技术要求难度大,特别是对于解剖结构需要熟悉掌握,另外有一定的学习曲线,手术医生接受的X射线辐射量大等缺点。国内外学者近年来陆续报道了微创手术治疗齿突骨折老年患者的病例,Wang[57]报道了5例老年齿状突Ⅱ型骨折患者行经皮前路3枚螺钉固定齿状突和双侧寰枢椎关节突治疗,手术时间93-114 min,术中出血量3-10 mL,无血管、脊髓神经、气管、食道损伤及内植物失败等并发症发生。复查颈椎X射线片示齿状突骨折均愈合,螺钉位置良好、寰枢椎稳定,患者术后临床效果满意。Kantelhardt等[58]报道了通过3D图像导航系统进行经皮微创颈后路寰枢椎内固定治疗Ⅱ型齿突骨折的3例老年患者,平均手术时间 106 min,术中出血量 194 mL,平均X射线曝光时间 3.8 min (395 cGy/cm2),术中成功置入双侧寰椎侧块螺钉及枢椎峡部螺钉,骨折复位良好。 "

| [1] Hagen S. CBO memorandum: projections of expenditures for long-term care services for the elderlyCBO memorandum: projections of expenditures for long-term care services for the elderly. Congressional Budget Office, Washington, DC, 1999.[2] Pal D, Sell P, Grevitt M. Type ll odontoid fractures in the elderly: an evidence-based narrative review of management. Eur Spine J. 2011; 20: 195-204.[3] Fassett DR, Harrop JS, Maltenfort M, et al. Mortality rates in geriatric patients with spinal cord injuries. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007; 7: 277-281.[4] Jackson AP, Haak MH, Khan N, et al. Cervical spine injuries in the elderly: acute postoperative mortality. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005; 30: 1524-1527.[5] Bohlman HH. Acute fractures and dislocations of the cervical spine. An analysis of three hundred hospitalized patients and review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1979; 61: 1119-1142.[6] Hadley MN, Dickman CA, Browner CM, et al. Acute axis fractures: a review of 229 cases. J Neurosurg. 1989; 71: 642-647.[7] Buchvald P, Capek L, Barsa P. [Odontoid bending stiffness after anterior fixation with a single lag screw: biomechanical study]. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech. 2015; 82: 235-238.[8] Harrop JS, Sharan AD, Przybylski GJ. Epidemiology of spinal cord injury after acute odontoid fractures. Neurosurg Focus. 2000; 8: e4.[9] Anderson LD, D'Alonzo RT. Fractures of the odontoid process of the axis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1974; 56: 1663-1674.[10] Hadley MN, Browner CM, Liu SS, et al. New subtype of acute odontoid fractures (type ll A). Neurosurgery. 1988; 22: 67-71.[11] Grauer JN, Shafi B, Hilibrand AS, et al. Proposal of a modified, treatment-oriented classification of odontoid fractures. Spine J. 2005; 5: 123-129.[12] Muller EJ, Schwinnen I, Fischer K, et al. Non-rigid immobilisation of odontoid fractures. Eur Spine J. 2003; 12: 522-525.[13] Lieberman IH, Webb JK. Cervical spine injuries in the elderly. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76: 877-881.[14] Ryan MD, Taylor TK. Odontoid fractures in the elderly. J Spinal Disord. 1993; 6:397-401.[15] Hanigan WC, Powell FC, Elwood PW, et al. Odontoid fractures in elderly patients. J Neurosurg.1993; 78: 32-35.[16] Joestl J, Lang NW, Tiefenboeck TM, et al. Management and Outcome of Dens Fracture Nonunions in Geriatric Patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98:193-198.[17] Perry J, Nickel VL. Total cervicalspine fusion for neck paralysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am.1959;41-a: 37-60.[18] Koller H, Zenner J, Hitzl W, et al. In vivo analysis of atlantoaxial motion in individuals immobilized with the halo thoracic vest or Philadelphia collar. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009; 34: 670-679.[19] Polin RS, Szabo T, Bogaev CA, et al. Nonoperative management of Types ll and llI odontoid fractures: the Philadelphia collar versus the halo vest. Neurosurgery. 1996; 38: 450-456; discussion 456-457.[20] Horn EM, Theodore N, Feiz-Erfan I, et al. Complications of halo fixation in the elderly. J Neurosurg Spine. 2006; 5: 46-49.[21] Tashjian RZ, Majercik S, Biffl WL, et al. Halo-vest immobilization increases early morbidity and mortality in elderly odontoid fractures. J Trauma. 2006; 60: 199-203.[22] Patel A, Zakaria R, Al-Mahfoudh R, et al. Conservative management of type ll and llI odontoid fractures in the elderly at a regional spine centre: A prospective and retrospective cohort study. Br J Neurosurg. 2015; 29: 249-253.[23] Majercik S, Tashjian RZ, Biffl WL, et al. Halo vest immobilization in the elderly: a death sentence? J Trauma. 2005; 59: 350-356; discussion 356-358.[24] van Middendorp JJ, Slooff WB, Nellestein WR, et al. Incidence of and risk factors for complications associated with halo-vest immobilization: a prospective, descriptive cohort study of 239 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009; 91: 71-79.[25] Winkler EA, Yue JK, Burke JF, et al. 188 Morbidity and Mortality Associated With Operative Management of Traumatic C2 Fractures in Octogenarians. Neurosurgery. 2016; 63 Suppl 1:174-175.[26] Schroeder GD, Kepler CK, Kurd MF, et al. A Systematic Review of the Treatment of Geriatric Type ll Odontoid Fractures. Neurosurgery. 2015; 77 Suppl 4: S6-14.[27] Robinson Y, Robinson AL, Olerud C. Systematic review on surgical and nonsurgical treatment of type ll odontoid fractures in the elderly. Biomed Res Int. 2014; 2014: 231948.[28] Frangen TM, Zilkens C, Muhr G, et al. Odontoid fractures in the elderly: dorsal C1/C2 fusion is superior to halo-vest immobilization. J Trauma. 2007; 63: 83-89.[29] Lennarson PJ, Mostafavi H, Traynelis VC, et al. Management of type ll dens fractures: a case-control study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000; 25: 1234-1237.[30] Chapman J, Smith JS, Kopjar B, et al. The AOSpine North America Geriatric Odontoid Fracture Mortality Study: a retrospective review of mortality outcomes for operative versus nonoperative treatment of 322 patients with long-term follow-up. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013; 38: 1098-1104.[31] Xu ZW, Liu TJ, He BR, et al. Transoral anterior release, odontoid partial resection, and reduction with posterior fusion for the treatment of irreducible atlantoaxial dislocation caused by odontoid fracture malunion. Eur Spine J. 2015;24: 694-701.[32] Schoenfeld AJ, Bono CM, Reichmann WM, et al. Type ll odontoid fractures of the cervical spine: do treatment type and medical comorbidities affect mortality in elderly patients? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011; 36: 879-885.[33] Ryken TC, Hadley MN, Aarabi B, et al. Management of isolated fractures of the axis in adults. Neurosurgery. 2013; 72 Suppl 2: 132-150.[34] Abou Madawi A, Solanki G, Casey AT, et al. Variation of the groove in the axis vertebra for the vertebral artery. Implications for instrumentation. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997; 79: 820-823.[35] Elliott RE, Tanweer O, Boah A, et al. Atlantoaxial fusion with transarticular screws: meta-analysis and review of the literature. World Neurosurg. 2013; 80: 627-641.[36] Currier BL, Todd LT, Maus TP, et al. Anatomic relationship of the internal carotid artery to the C1 vertebra: A case report of cervical reconstruction for chordoma and pilot study to assess the risk of screw fixation of the atlas. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003; 28: E461-467.[37] Ebraheim NA, Misson JR, Xu R, et al. The optimal transarticular c1-2 screw length and the location of the hypoglossal nerve. Surg Neurol. 2000; 53: 208-210.[38] Tan M, Wang H, Wang Y, et al. Morphometric evaluation of screw fixation in atlas via posterior arch and lateral mass. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003;28: 888-895.[39] Stulik J, Vyskocil T, Sebesta P, et al. Atlantoaxial fixation using the polyaxial screw-rod system. Eur Spine J. 2007; 16: 479-484.[40] Vaccaro AR, Kepler CK, Kopjar B, et al. Functional and quality-of-life outcomes in geriatric patients with type- ll dens fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95: 729-735.[41] Ryang YM, Torok E, Janssen I, et al. Early Morbidity and Mortality in 50 Very Elderly Patients After Posterior Atlantoaxial Fusion for Traumatic Odontoid Fractures. World Neurosurg. 2016; 87: 381-391.[42] Apfelbaum RI, Lonser RR, Veres R, et al. Direct anterior screw fixation for recent and remote odontoid fractures. J Neurosurg. 2000; 93: 227-236.[43] Bohler J. Anterior stabilization for acute fractures and non-unions of the dens. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982; 64: 18-27.[44] Lohrer L, Raschke MJ, Thiesen D, et al. Current concepts in the treatment of Anderson Type ll odontoid fractures in the elderly in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. Injury. 2012; 43: 462-469.[45] Borm W, Kast E, Richter HP, et al. Anterior screw fixation in type ll odontoid fractures: is there a difference in outcome between age groups? Neurosurgery. 2003; 52: 1089-1092; discussion 1092-1084.[46] Waschke A, Ullrich B, Kalff R, et al. Cement-augmented anterior odontoid screw fixation for osteoporotic type ll odontoid fractures in elderly patients: prospective evaluation of 11 patients. Eur Spine J. 2016; 25: 115-121.[47] Andersson S, Rodrigues M, Olerud C. Odontoid fractures: high complication rate associated with anterior screw fixation in the elderly. Eur Spine J. 2000; 9: 56-59.[48] Vasudevan K, Grossberg JA, Spader HS, et al. Age increases the risk of immediate postoperative dysphagia and pneumonia after odontoid screw fixation. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2014; 126: 185-189.[49] Etter C. Combined anterior screw fixation of an odontoid fracture and the atlanto-axial joints (C1/C2) in a geriatric patient. Eur Spine J. 2016.[50] Osti M, Philipp H, Meusburger B, et al. Analysis of failure following anterior screw fixation of Type ll odontoid fractures in geriatric patients. Eur Spine J. 2011; 20: 1915-1920.[51] Lakshmanan P, Jones A, Howes J, et al. CT evaluation of the pattern of odontoid fractures in the elderly--relationship to upper cervical spine osteoarthritis. Eur Spine J. 2005; 14: 78-83.[52] Dailey AT, Hart D, Finn MA, et al. Anterior fixation of odontoid fractures in an elderly population. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010; 12: 1-8.[53] Koivikko MP, Kiuru MJ, Koskinen SK, et al. Factors associated with nonunion in conservatively-treated type- ll fractures of the odontoid process. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004; 86: 1146-1151.[54] Madhavan K, Chieng LO, Foong H, et al. Surgical outcomes of elderly patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy: a meta-analysis of studies reporting on 2868 patients. Neurosurg Focus. 2016; 40: E13.[55] Koga FA, El Dib R, Wakasugui W, et al. Anesthesia-Related and Perioperative Cardiac Arrest in Low- and High-Income Countries: A Systematic Review With Meta-Regression and Proportional Meta-Analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015; 94: e1465.[56] 池永龙,徐华梓,王向阳,等. 老年人上颈椎损伤微创与开放手术治疗的比较[J]. 中国脊柱脊髓杂志,2009,19(7):492-496.[57] Wang J, Zheng W, Zhang Z, et al. [Percutaneous anterior odontoid and transarticular screw fixation for type ll odontoid fractures in elderly patients]. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2013; 27: 1090-1093.[58] Kantelhardt SR, Keric N, Conrad J, et al. Minimally invasive instrumentation of uncomplicated cervical fractures. Eur Spine J. 2016;25: 127-133.[59] Molinari RW, Dahl J, Gruhn WL, et al. Functional outcomes, morbidity, mortality, and fracture healing in 26 consecutive geriatric odontoid fracture patients treated with posterior fusion. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2013; 26: 119-126.[60] Steltzlen C, Lazennec JY, Catonne Y, et al. Unstable odontoid fracture: surgical strategy in a 22-case series, and literature review. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2013;99: 615-623.[61] Crockard HA, Heilman AE, Stevens JM. Progressive myelopathy secondary to odontoid fractures: clinical, radiological, and surgical features. J Neurosurg. 1993;78: 579-586.[62] Woods BI, Hohl JB, Braly B, et al. Mortality in elderly patients following operative and nonoperative management of odontoid fractures. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2014;27: 321-326. |

| [1] | Xue Yadong, Zhou Xinshe, Pei Lijia, Meng Fanyu, Li Jian, Wang Jinzi . Reconstruction of Paprosky III type acetabular defect by autogenous iliac bone block combined with titanium plate: providing a strong initial fixation for the prosthesis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(9): 1424-1428. |

| [2] | Zhuang Zhikun, Wu Rongkai, Lin Hanghui, Gong Zhibing, Zhang Qianjin, Wei Qiushi, Zhang Qingwen, Wu Zhaoke. Application of stable and enhanced lined hip joint system in total hip arthroplasty in elderly patients with femoral neck fractures complicated with hemiplegia [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(9): 1429-1433. |

| [3] | Yao Xiaoling, Peng Jiancheng, Xu Yuerong, Yang Zhidong, Zhang Shuncong. Variable-angle zero-notch anterior interbody fusion system in the treatment of cervical spondylotic myelopathy: 30-month follow-up [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(9): 1377-1382. |

| [4] | Jiang Huanchang, Zhang Zhaofei, Liang De, Jiang Xiaobing, Yang Xiaodong, Liu Zhixiang. Comparison of advantages between unilateral multidirectional curved and straight vertebroplasty in the treatment of thoracolumbar osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(9): 1407-1411. |

| [5] | Li Wei, Zhu Hanmin, Wang Xin, Gao Xue, Cui Jing, Liu Yuxin, Huang Shuming. Effect of Zuogui Wan on bone morphogenetic protein 2 signaling pathway in ovariectomized osteoporosis mice [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(8): 1173-1179. |

| [6] | Wang Jing, Xiong Shan, Cao Jin, Feng Linwei, Wang Xin. Role and mechanism of interleukin-3 in bone metabolism [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(8): 1260-1265. |

| [7] | Xiao Hao, Liu Jing, Zhou Jun. Research progress of pulsed electromagnetic field in the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(8): 1266-1271. |

| [8] | Wu Bingshuang, Wang Zhi, Tang Yi, Tang Xiaoyu, Li Qi. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: from enthesis to tendon-to-bone healing [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(8): 1293-1298. |

| [9] | An Weizheng, He Xiao, Ren Shuai, Liu Jianyu. Potential of muscle-derived stem cells in peripheral nerve regeneration [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(7): 1130-1136. |

| [10] | Hou Jingying, Guo Tianzhu, Yu Menglei, Long Huibao, Wu Hao. Hypoxia preconditioning targets and downregulates miR-195 and promotes bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell survival and pro-angiogenic potential by activating MALAT1 [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(7): 1005-1011. |

| [11] | Liang Xuezhen, Yang Xi, Li Jiacheng, Luo Di, Xu Bo, Li Gang. Bushen Huoxue capsule regulates osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation of rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells via Hedgehog signaling pathway [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(7): 1020-1026. |

| [12] | Wu Weiyue, Guo Xiaodong, Bao Chongyun. Application of engineered exosomes in bone repair and regeneration [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(7): 1102-1106. |

| [13] | Zhou Hongqin, Wu Dandan, Yang Kun, Liu Qi. Exosomes that deliver specific miRNAs can regulate osteogenesis and promote angiogenesis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(7): 1107-1112. |

| [14] | Zhang Jinglin, Leng Min, Zhu Boheng, Wang Hong. Mechanism and application of stem cell-derived exosomes in promoting diabetic wound healing [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(7): 1113-1118. |

| [15] | Cui Xing, Sun Xiaoqi, Zheng Wei, Ma Dexin. Huangqin Decoction regulates autophagy to intervene with intestinal acute graft-versus-host disease in mice [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(7): 1057-1062. |

| Viewed | ||||||

|

Full text |

|

|||||

|

Abstract |

|

|||||