Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research ›› 2017, Vol. 21 ›› Issue (17): 2776-2782.doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-4344.2017.17.024

Previous Articles Next Articles

The immunomodulatory function and clinical applications of mesenchymal stem cells

Yang Yan-mei1, Jiang Xiao-xia2, Wen Ning1

- 1Department of Stomatology, Chinese PLA General Hospital, Beijing 100853, China; 2Department of Advanced Interdisciplinary Studies, Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, Academy of Military Medical Sciences, Beijing 100850, China

-

Revised:2017-05-02Online:2017-06-18Published:2017-06-29 -

Contact:Wen Ning, Chief physician, Professor, Department of Stomatology, Chinese PLA General Hospital, Beijing 100853, China -

About author:Yang Yan-mei, Studying for doctorate, Department of Stomatology, Chinese PLA General Hospital, Beijing 100853, China -

Supported by:the National Hight-Technology Research and Development Project of China (“863” Program), No. 2013AA032201; the Natural Science Foundation of Beijing, No. 7162142; the National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 81271936

CLC Number:

Cite this article

Yang Yan-mei, Jiang Xiao-xia, Wen Ning. The immunomodulatory function and clinical applications of mesenchymal stem cells[J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2017, 21(17): 2776-2782.

share this article

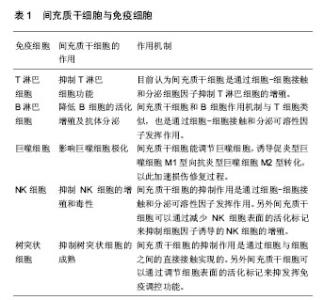

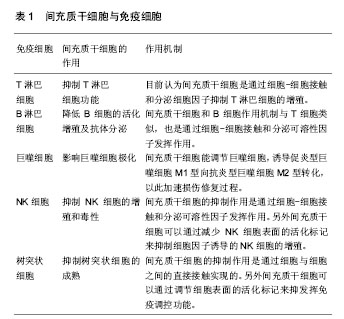

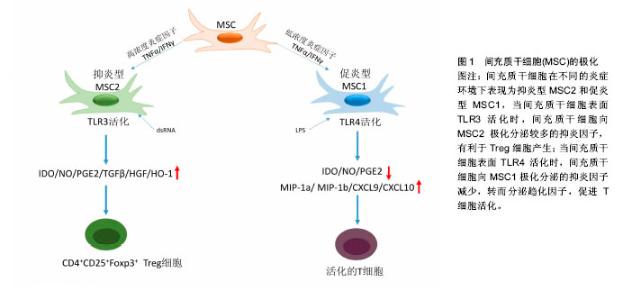

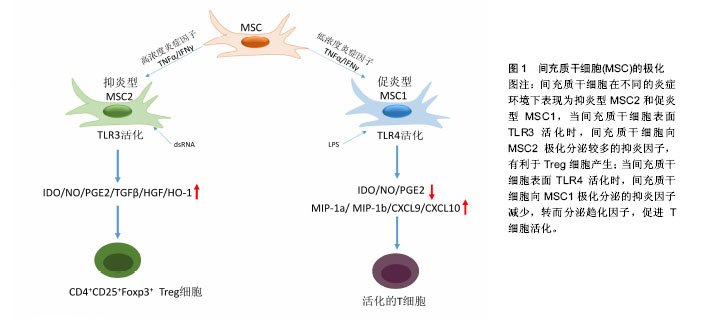

2.1.1 MSCs与T淋巴细胞 T淋巴细胞在许多自身免疫疾病和炎症疾病的起始和发展中都起到了非常重要的作用。因此人们广泛地研究MSCs对T淋巴细胞活化、增殖、分化的调节。其中就有研究指出在混合淋巴细胞反应(MLR)或是受多克隆活化剂刺激后,人MSCs能抑制T淋巴细胞的增殖[10]。同样,在小鼠MSCs中也发现了其对T淋巴细胞的抑制作用[11]。并且Djouad等[12]报道了MSCs在体内的免疫抑制特性,当小鼠MSCs与黑色素瘤细胞共同移植时,促进了黑色素瘤的生长。MSCs对T淋巴细胞增殖的抑制,学者认为是抑制了细胞分裂使细胞周期停留在G0/G1期,而并不是诱导细胞凋亡,相反MSCs还能减少T淋巴细胞的凋亡,支持T淋巴细胞的存活[13]。目前认为MSCs是通过细胞-细胞接触和分泌细胞因子抑制T淋巴细胞的增殖。Di Nicola等[13]用Transwell将MSCs与培养体系分隔培养时,MSCs仍然可以发挥免疫抑制作用,说明MSCs的这种免疫抑制能力可能是通过可溶性因子介导的。但是,与之矛盾的是Krampera等[11]用MSCs培养的上清或Transwell培养实验并未观察到抑制效果,他们认为MSCs对T淋巴细胞的增殖抑制是通过这两种细胞的直接接触实现的。MSCs受到INF-γ刺激后,细胞黏附分子如程序性死亡受体(PD-L1,CD274)、血管细胞黏附分子(VCAM-1)的表达上调,这不仅促进了细胞-细胞的接触,同时促进了MSCs对T淋巴细胞的抑制[14-15]。以下的这些可溶性因子在MSCs对T淋巴细胞抑制的过程中不容忽视,包括转化生长因子β1(TGF-β1)、吲哚胺2,3双加氧酶(IDO)、一氧化氮(NO)、白细胞介素10(IL-10)、前列腺素E2(PGE2)、肝细胞生长因子(HGF)、血红素氧合酶(HO-1)和白血病抑制因子(LIF)[16]。这些因子大多数不是MSCs自然产生的,而是需要IFN-γ单独或者联合肿瘤坏死因子α(TNF-α)、白细胞介素α、白细胞介素1β或者白细胞介素17 [16-17],诱导MSCs产生各种各样的酶和可溶性因子比如环氧酶2(COX-2)、前列腺素E2和吲哚胺2,3双加氧酶来介导免疫抑制的能力。 在病原体或损伤激活的情况下,CD4+辅助性T淋巴细胞(Th0)根据T淋巴细胞微环境可以分化为Th1、Th2、Th17或者调节性T淋巴细胞(Tregs)。而MSCs能调节这些细胞亚群的分化、功能和平衡,并促进抗炎免疫反应的发展。MSCs能抑制Th1对促炎症因子IFN-γ的分泌,上调Th2分泌抗炎症因子白细胞介素4 [18]。MSCs还能通过上调PD-1的表达、增强白细胞介素10的分泌、增加前列腺素E2的产生或者通过CC趋化因子配体2(CCL-2)方式抑制Th17的分化[19-22]。另外,MSCs还能促进白细胞介素10的分泌以及Foxp3转录因子的表达,这提示Th0向Tregs分化[23]。而且报道发现MSCs能促进Th1和Th17分化体系中CD4+CD25+Foxp3+Tregs的增加[24],另外在MSC-外周血单核细胞共培养体系中MSCs能诱导CD8+ Tregs细胞的产生[25]。大量文献显示MSC是通过分泌转化生长因子β,白细胞介素6,白细胞介素10或表达吲哚胺2,3双加氧酶促进Treg分化[18-19]。目前,MSCs对T淋巴细胞调控机制的研究主要集中在其抑制免疫方面。 2.1.2 MSCs与B淋巴细胞 B淋巴细胞是适应性免疫中另一种重要的免疫细胞,主要负责体液免疫和产生抗体。有研究认为MSCs通过使细胞停留在G0/G1期来抑制B淋巴细胞增殖,而不是诱导凋亡[26]。另外当MSCs和B淋巴细胞共培养时,能减少B细胞产生IgG,IgM,IgA抗体,并且还能抑制B细胞表面趋化因子受体的表达,包括CXCR4、CXCR5和CXCR7,改变B细胞的趋化特性[26-28]。MSCs和B细胞作用机制与T细胞类似,也是通过细胞-细胞接触和分泌可溶性因子发挥作用的,报道称MSCs通过PD-1/PD-L1与B细胞直接接触来抑制其功能[29]。也有研究认为这种抑制作用和B淋巴细胞诱导成熟蛋白1(Blimp-1)的mRNA表达下调有关,Blimp-1是B细胞终末分化重要的转录因子。近期,Rosado等[27]发现MSCs抑制B细胞增殖和抗体产生,但必须在CD3+T细胞存在的情况下。不过,也有研究发现MSCs增强了B细胞活性,促进了抗体的分泌[30]。 2.1.3 MSCs与巨噬细胞 巨噬细胞是固有免疫反应中一类细胞,来源于单核细胞,它的功能也受到MSCs的调节。巨噬细胞对微环境的反应表现出较高的可塑性,因此巨噬细胞可以分为两型:促炎型巨噬细胞M1型和抗炎型巨噬细胞M2型[31]。最近几年的研究发现MSCs能调节巨噬细胞,诱导M1型向M2型转化,以此加速损伤修复过程[32]。Prockop等[33]指出,MSCs对巨噬细胞的影响是通过两个负反馈循环实现的。在炎症环境下,巨噬细胞释放促炎因子活化MSCs,使其通过上调的COX2分泌前列腺素E2,最终促使巨噬细胞向M2型转变;另一种方式是活化的MSCs分泌TSG-6(一种抗炎分子),和巨噬细胞表面的CD44结合,扰乱了其与TLR2的相互作用,降低了TLR2/NFκB的信号,从而降低了炎症反应。另外,Melief等[34]指出MSCs能直接诱导单核细胞成为M2巨噬细胞,在这个过程中,MSCs的吲哚胺2,3双加氧酶活性和白细胞介素10非依赖方式的T细胞抑制参与其中。小胶质细胞也受到MSCs的调控,并且和巨噬细胞类似,能从促炎的M1型转化为抗炎的M2型,这主要和MSCs释放CX3CL1以及上调小胶质细胞的CX3CR1/CX3CL1轴有关[35]。在小鼠动物实验中也验证了这一结论,当脑损伤后在侧脑室注射人MSCs后,小胶质细胞极化为M2表型,同时伴随吞噬作用的下降,神经功能的早期修复以及损伤区改善的变化[36]。 2.1.4 MSCs与自然杀伤细胞(NK细胞) NK细胞是固有免疫的重要效应细胞,具有细胞溶解毒性,参与机体对感染和癌症的防御。NK细胞通过分泌许多炎症因子,比如肿瘤坏死因子α和IFN-γ来实现它们的效应功能。越来越多的研究表明MSCs能抑制白细胞介素2、白细胞介素15诱导的静息NK细胞的增殖,并且MSCs的抑制能力和MSCs︰NK的细胞比例有关,比例越高抑制能力越强;但是MSCs不能抑制已经激活的NK细胞的增殖,反而会清除自体和异体MSCs[37]。MSCs的抑制作用是通过可溶性因子如吲哚胺2,3双加氧酶、前列腺素E2、sHLAG5实现的[38-39],不过MSCs破坏NK细胞的毒性则是通过细胞-细胞接触实现的。另外MSCs可以通过减少NK细胞表面的活化标记,如NKp44、NKp30、NKG2D和CD132 [37],来抑制细胞因子诱导的NK细胞的增殖。 2.1.5 MSCs与树突状细胞 树突状细胞是机体最重要的抗原递呈细胞,在体内树突状细胞来源于骨髓中CD34+细胞,体外来自白细胞介素4和粒细胞巨噬细胞集落刺激因子刺激的单核细胞。树突状细胞主要的功能是加工、递呈抗原给记忆性T细胞,从而启动T细胞介导的免疫反应。MSCs能改变树突状细胞的表型、细胞因子释放、分化和成熟以及抗原递呈的能力。Ramasamy等[40]提出单核细胞向树突状细胞分化时,MSCs能使其停留在G0期从而抑制其增殖,并且MSCs抑制树突状细胞分化过程中MHC、CD40、CD80、CD86的上调,抑制树突状细胞成熟过程中CD40、CD83、CD86的增加并且抑制树突状细胞的内吞作用,不过MSCs的这个作用是可逆的。另外在MSCs存在的情况下,单核细胞向树突状细胞分化过程中,肿瘤坏死因子α和白细胞介素12减少,而白细胞介素12是T细胞向Th1分化以及活化的T细胞和NK细胞分泌INF-γ的有效调节因子;相反MSCs使树突状细胞产生高水平的抑炎因子[41-42]。也有研究称MSCs分泌的细胞因子,比如前列腺素E2和白细胞介素6对抑制树突状细胞的分化起到作用[42-43]。 2.2 MSCs的极化 大量关于MSCs免疫调控能力的研究都集中在MSCs的免疫抑制方面,但随着研究的进一步深入,发现不同的炎症微环境可以使MSCs具有和巨噬细胞类似的M1和M2两种独特的类型,及促炎型MSC1和抑炎型MSC2[44],进而使MSCs的免疫调控作用变得更为复杂。 一氧化氮和吲哚胺2,3双加氧酶在MSCs遇到淋巴细胞发挥免疫调节作用中起着关键的作用。MSCs产生一氧化氮和吲哚胺2,3双加氧酶表明了MSCs对淋巴细胞的免疫抑制作用,所以抑制一氧化氮和吲哚胺2,3双加氧酶能够减弱MSCs对淋巴细胞的作用。当组织损伤时,局部分泌的炎症递质使得巨噬细胞活化成为促进炎症的M1型巨噬细胞,而M1型巨噬细胞能够产生高浓度的促进炎症的刺激物,包括肿瘤坏死因子α和IFN-γ,从而能够使MSCs获得抑炎的表型即MSC2,同时产生趋化因子趋化淋巴细胞来到损伤区。此时MSCs分泌大量的一氧化氮和吲哚胺2,3双加氧酶,抑制了淋巴细胞的效应功能。总体的效应就是减弱了免疫反应,减少了组织的损伤。但是在长期慢性的炎症环境中,单核细胞分化为抑制炎症的M2型巨噬细胞,此时肿瘤坏死因子α和IFN-γ浓度处于一个较低的水平,这样就不足以激活MSCs的免疫抑制能力,使其成为MSC1;但是MSCs仍然能够分泌趋化因子,例如CXCL9、CXCL10招募淋巴细胞到炎症区域并且增强了淋巴细胞的效应。同时因为一氧化氮和吲哚胺2,3双加氧酶水平不足,MSCs就不能控制效应淋巴细胞产生的免疫反应,表现出炎症反应的加剧以及组织的损伤[45]。 Waterman等[44]指出特异的Toll样受体(TLRs)的激活和MSCs的免疫调节能力之间的重要关系。TLRs是天然免疫中的一类重要的蛋白质分子,能够识别微生物例如革兰阴性菌脂多糖、热休克蛋白、脂壁酸、鞭毛蛋白及病毒复制中间产物dsRNA等。TLRs不仅存在于各种免疫细胞表面,更是在MSCs表面表达,而且对MSCs表现出何种免疫调节能力起着重要作用。研究发现,TLR4的活化可以使MSCs转化为促炎的MSC1亚型,而TLR3的活化则可以使MSCs转化为抗炎的MSC2亚型。在外源性刺激物dsRNA存在情况下,MSCs表面的TLR3被活化,使得MSCs向MSC2亚型极化,分泌大量的抑炎因子吲哚胺2,3双加氧酶、一氧化氮、前列腺素E2、转化生长因子β、肝细胞生长因子、血红素氧合酶等,抑制了T细胞的增殖,有利于Tregs的产生,从而表现出免疫抑制功能;而在脂多糖存在下,MSCs表面的TLR4被活化,使得MSCs向MSC1亚型极化,抑炎因子吲哚胺2,3双加氧酶、一氧化氮、前列腺素E2的产生明显减少,转而分泌一些趋化因子如巨噬细胞炎性蛋白1a(MIP-1a)、MIP-1b、RANTES、CXCL9、CXCL10等,招募淋巴细胞到炎症部位并且增强T细胞介导的免疫反应,从而促进了炎症反应[46](图1)。"

| [1] Dazzi F, Krampera M. Mesenchymal stem cells and autoimmune diseases. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2011; 24(1):49-57.[2] Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, et al. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284(5411):143-147.[3] Friedenstein AJ, Deriglasova UF, Kulagina NN, et al. Precursors for fibroblasts in different populations of hematopoietic cells as detected by the in vitro colony assay method. Exp Hematol. 1974;2(2):83-92.[4] Castro-Manrreza ME, Montesinos JJ. Immunoregulation by mesenchymal stem cells: biological aspects and clinical applications. J Immunol Res. 2015;2015:394917.[5] Le Blanc K, Rasmusson I, Sundberg B, et al. Treatment of severe acute graft-versus-host disease with third party haploidentical mesenchymal stem cells. Lancet. 2004; 363(9419):1439-1441.[6] Ma S, Xie N, Li W, et al. Immunobiology of mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Death Differ. 2014;21(2):216-225.[7] Krampera M. Mesenchymal stromal cells: more than inhibitory cells. Leukemia. 2011;25(4):565-566.[8] Li W, Ren G, Huang Y, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells: a double-edged sword in regulating immune responses. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19(9):1505-1513.[9] English K. Mechanisms of mesenchymal stromal cell immunomodulation. Immunol Cell Biol. 2013;91(1):19-26.[10] Bartholomew A, Sturgeon C, Siatskas M, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells suppress lymphocyte proliferation in vitro and prolong skin graft survival in vivo. Exp Hematol. 2002; 30(1): 42-48.[11] Krampera M, Glennie S, Dyson J, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells inhibit the response of naive and memory antigen-specific T cells to their cognate peptide. Blood. 2003;101(9):3722-3729.[12] Djouad F, Plence P, Bony C, et al. Immunosuppressive effect of mesenchymal stem cells favors tumor growth in allogeneic animals. Blood. 2003;102(10):3837-3844.[13] Di Nicola M, Carlo-Stella C, Magni M, et al. Human bone marrow stromal cells suppress T-lymphocyte proliferation induced by cellular or nonspecific mitogenic stimuli. Blood. 2002;99(10):3838-3843.[14] Najar M, Raicevic G, Fayyad-Kazan H, et al. Immune-related antigens, surface molecules and regulatory factors in human-derived mesenchymal stromal cells: the expression and impact of inflammatory priming. Stem Cell Rev. 2012; 8(4):1188-1198.[15] Ren G, Zhao X, Zhang L, et al. Inflammatory cytokine-induced intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 in mesenchymal stem cells are critical for immunosuppression. J Immunol. 2010;184(5):2321-2328.[16] Ren G, Zhang L, Zhao X, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-mediated immunosuppression occurs via concerted action of chemokines and nitric oxide. Cell Stem Cell. 2008; 2(2):141-150.[17] Han X, Yang Q, Lin L, et al. Interleukin-17 enhances immunosuppression by mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Death Differ. 2014;21(11):1758-1768.[18] Aggarwal S, Pittenger MF. Human mesenchymal stem cells modulate allogeneic immune cell responses. Blood. 2005; 105(4):1815-1822.[19] Qu X, Liu X, Cheng K, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit Th17 cell differentiation by IL-10 secretion. Exp Hematol. 2012;40(9):761-770.[20] Luz-Crawford P, Noël D, Fernandez X, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells repress Th17 molecular program through the PD-1 pathway. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e45272.[21] Duffy MM, Pindjakova J, Hanley SA, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell inhibition of T-helper 17 cell- differentiation is triggered by cell-cell contact and mediated by prostaglandin E2 via the EP4 receptor. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41(10):2840-2851.[22] Rafei M, Campeau PM, Aguilar-Mahecha A, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells ameliorate experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by inhibiting CD4 Th17 T cells in a CC chemokine ligand 2-dependent manner. J Immunol. 2009;182(10):5994-6002.[23] Ghannam S, Pène J, Moquet-Torcy G, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit human Th17 cell differentiation and function and induce a T regulatory cell phenotype. J Immunol. 2010; 185(1):302-312.[24] Luz-Crawford P, Kurte M, Bravo-Alegría J, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells generate a CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cell population during the differentiation process of Th1 and Th17 cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2013;4(3):65.[25] Prevosto C, Zancolli M, Canevali P, et al. Generation of CD4+ or CD8+ regulatory T cells upon mesenchymal stem cell- lymphocyte interaction. Haematologica. 2007;92(7):881-888.[26] Corcione A, Benvenuto F, Ferretti E, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells modulate B-cell functions. Blood. 2006;107(1):367-372.[27] Rosado MM, Bernardo ME, Scarsella M, et al. Inhibition of B-cell proliferation and antibody production by mesenchymal stromal cells is mediated by T cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2015; 24(1): 93-103.[28] Tabera S, Pérez-Simón JA, Díez-Campelo M, et al. The effect of mesenchymal stem cells on the viability, proliferation and differentiation of B-lymphocytes. Haematologica. 2008;93(9): 1301-1309.[29] Augello A, Tasso R, Negrini SM, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal progenitor cells inhibit lymphocyte proliferation by activation of the programmed death 1 pathway. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35(5):1482-1490.[30] Rasmusson I, Le Blanc K, Sundberg B, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells stimulate antibody secretion in human B cells. Scand J Immunol. 2007;65(4):336-343.[31] Murray PJ, Allen JE, Biswas SK, et al. Macrophage activation and polarization: nomenclature and experimental guidelines. Immunity. 2014;41(1):14-20.[32] Bernardo ME, Fibbe WE. Mesenchymal stromal cells: sensors and switchers of inflammation. Cell Stem Cell. 2013; 13(4):392-402.[33] Prockop DJ. Concise review: two negative feedback loops place mesenchymal stem/stromal cells at the center of early regulators of inflammation. Stem Cells. 2013;31(10): 2042-2046.[34] Melief SM, Schrama E, Brugman MH, et al. Multipotent stromal cells induce human regulatory T cells through a novel pathway involving skewing of monocytes toward anti-inflammatory macrophages. Stem Cells. 2013;31(9): 1980-1991.[35] Giunti D, Parodi B, Usai C, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells shape microglia effector functions through the release of CX3CL1. Stem Cells. 2012;30(9):2044-2053.[36] Zuk PA, Zhu M, Ashjian P, et al. Human adipose tissue is a source of multipotent stem cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13(12): 4279-4295.[37] Spaggiari GM, Capobianco A, Becchetti S, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-natural killer cell interactions: evidence that activated NK cells are capable of killing MSCs, whereas MSCs can inhibit IL-2-induced NK-cell proliferation. Blood. 2006;107(4):1484-1490.[38] Spaggiari GM, Capobianco A, Abdelrazik H, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit natural killer-cell proliferation, cytotoxicity, and cytokine production: role of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and prostaglandin E2. Blood. 2008;111(3): 1327-1333.[39] Selmani Z, Naji A, Zidi I, et al. Human leukocyte antigen-G5 secretion by human mesenchymal stem cells is required to suppress T lymphocyte and natural killer function and to induce CD4+CD25highFOXP3+ regulatory T cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26(1):212-222.[40] Ramasamy R, Fazekasova H, Lam EW, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit dendritic cell differentiation and function by preventing entry into the cell cycle. Transplantation. 2007; 83(1): 71-76.[41] Chiesa S, Morbelli S, Morando S, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells impair in vivo T-cell priming by dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(42):17384-17389.[42] Spaggiari GM, Abdelrazik H, Becchetti F, et al. MSCs inhibit monocyte-derived DC maturation and function by selectively interfering with the generation of immature DCs: central role of MSC-derived prostaglandin E2. Blood. 2009;113(26): 6576-6583.[43] Djouad F, Charbonnier LM, Bouffi C, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit the differentiation of dendritic cells through an interleukin-6-dependent mechanism. Stem Cells. 2007;25(8): 2025-2032.[44] Waterman RS, Tomchuck SL, Henkle SL, et al. A new mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) paradigm: polarization into a pro-inflammatory MSC1 or an Immunosuppressive MSC2 phenotype. PLoS One. 2010;5(4):e10088.[45] Kim N, Cho SG. Overcoming immunoregulatory plasticity of mesenchymal stem cells for accelerated clinical applications. Int J Hematol. 2016;103(2):129-137.[46] Yan H, Wu M, Yuan Y, et al. Priming of Toll-like receptor 4 pathway in mesenchymal stem cells increases expression of B cell activating factor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;448(2):212-217.[47] Waterman RS, Henkle SL, Betancourt AM. Mesenchymal stem cell 1 (MSC1)-based therapy attenuates tumor growth whereas MSC2-treatment promotes tumor growth and metastasis. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e45590.[48] Lazarus HM, Haynesworth SE, Gerson SL, et al. Ex vivo expansion and subsequent infusion of human bone marrow-derived stromal progenitor cells (mesenchymal progenitor cells): implications for therapeutic use. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;16(4):557-564.[49] Ball LM, Bernardo ME, Roelofs H, et al. Multiple infusions of mesenchymal stromal cells induce sustained remission in children with steroid-refractory, grade III-IV acute graft-versus-host disease. Br J Haematol. 2013;163(4): 501-509.[50] von Bonin M, Stölzel F, Goedecke A, et al. Treatment of refractory acute GVHD with third-party MSC expanded in platelet lysate-containing medium. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2009;43(3):245-251.[51] Müller I, Kordowich S, Holzwarth C, et al. Application of multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells in pediatric patients following allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2008;40(1):25-32.[52] Li X, Wang D, Liang J, et al. Mesenchymal SCT ameliorates refractory cytopenia in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48(4): 544-550. |

| [1] | Yao Xiaoling, Peng Jiancheng, Xu Yuerong, Yang Zhidong, Zhang Shuncong. Variable-angle zero-notch anterior interbody fusion system in the treatment of cervical spondylotic myelopathy: 30-month follow-up [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(9): 1377-1382. |

| [2] | Wang Jing, Xiong Shan, Cao Jin, Feng Linwei, Wang Xin. Role and mechanism of interleukin-3 in bone metabolism [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(8): 1260-1265. |

| [3] | Xiao Hao, Liu Jing, Zhou Jun. Research progress of pulsed electromagnetic field in the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(8): 1266-1271. |

| [4] | Tian Chuan, Zhu Xiangqing, Yang Zailing, Yan Donghai, Li Ye, Wang Yanying, Yang Yukun, He Jie, Lü Guanke, Cai Xuemin, Shu Liping, He Zhixu, Pan Xinghua. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells regulate ovarian aging in macaques [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(7): 985-991. |

| [5] | Hou Jingying, Guo Tianzhu, Yu Menglei, Long Huibao, Wu Hao. Hypoxia preconditioning targets and downregulates miR-195 and promotes bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell survival and pro-angiogenic potential by activating MALAT1 [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(7): 1005-1011. |

| [6] | Zhou Ying, Zhang Huan, Liao Song, Hu Fanqi, Yi Jing, Liu Yubin, Jin Jide. Immunomodulatory effects of deferoxamine and interferon gamma on human dental pulp stem cells [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(7): 1012-1019. |

| [7] | Liang Xuezhen, Yang Xi, Li Jiacheng, Luo Di, Xu Bo, Li Gang. Bushen Huoxue capsule regulates osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation of rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells via Hedgehog signaling pathway [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(7): 1020-1026. |

| [8] | Wen Dandan, Li Qiang, Shen Caiqi, Ji Zhe, Jin Peisheng. Nocardia rubra cell wall skeleton for extemal use improves the viability of adipogenic mesenchymal stem cells and promotes diabetes wound repair [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(7): 1038-1044. |

| [9] | Zhu Bingbing, Deng Jianghua, Chen Jingjing, Mu Xiaoling. Interleukin-8 receptor enhances the migration and adhesion of umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells to injured endothelium [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(7): 1045-1050. |

| [10] | Fang Xiaolei, Leng Jun, Zhang Chen, Liu Huimin, Guo Wen. Systematic evaluation of different therapeutic effects of mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in the treatment of ischemic stroke [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(7): 1085-1092. |

| [11] | Guo Jia, Ding Qionghua, Liu Ze, Lü Siyi, Zhou Quancheng, Gao Yuhua, Bai Chunyu. Biological characteristics and immunoregulation of exosomes derived from mesenchymal stem cells [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(7): 1093-1101. |

| [12] | Zhang Jinglin, Leng Min, Zhu Boheng, Wang Hong. Mechanism and application of stem cell-derived exosomes in promoting diabetic wound healing [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(7): 1113-1118. |

| [13] | An Weizheng, He Xiao, Ren Shuai, Liu Jianyu. Potential of muscle-derived stem cells in peripheral nerve regeneration [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(7): 1130-1136. |

| [14] | Huang Chuanjun, Zou Yu, Zhou Xiaoting, Zhu Yangqing, Qian Wei, Zhang Wei, Liu Xing. Transplantation of umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells encapsulated in RADA16-BDNF hydrogel promotes neurological recovery in an intracerebral hemorrhage rat model [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(4): 510-515. |

| [15] | He Yunying, Li Lingjie, Zhang Shuqi, Li Yuzhou, Yang Sheng, Ji Ping. Method of constructing cell spheroids based on agarose and polyacrylic molds [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(4): 553-559. |

| Viewed | ||||||

|

Full text |

|

|||||

|

Abstract |

|

|||||