Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research ›› 2016, Vol. 20 ›› Issue (50): 7507-7517.doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-4344.2016.50.00

Previous Articles Next Articles

Transplantation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells overexpressing Shootin1 for treatment of spinal cord injury

Zhang Wei1, Zhu Xiao-qi1, Zhang De-cai2

- 1Affiliated Baoan Hospital of Shenzhen, Southern Medical University, Shenzhen 518101, Guangdong Province, China

2Luohu District Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shenzhen 518001, Guangdong Province, China

-

Revised:2016-09-21Online:2016-12-02Published:2016-12-02 -

Contact:Zhu Xiao-qi, M.D., Chief physician, Affiliated Baoan Hospital of Shenzhen, Southern Medical University, Shenzhen 518101, Guangdong Province, China -

About author:Zhang Wei, Studying for master’s degree, Affiliated Baoan Hospital of Shenzhen, Southern Medical University, Shenzhen 518101, Guangdong Province, China -

Supported by:a grant from the Shenzhen Scientific Innovation Committee, No. JCYJ20130329090921096

CLC Number:

Cite this article

Zhang Wei, Zhu Xiao-qi, Zhang De-cai . Transplantation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells overexpressing Shootin1 for treatment of spinal cord injury[J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2016, 20(50): 7507-7517.

share this article

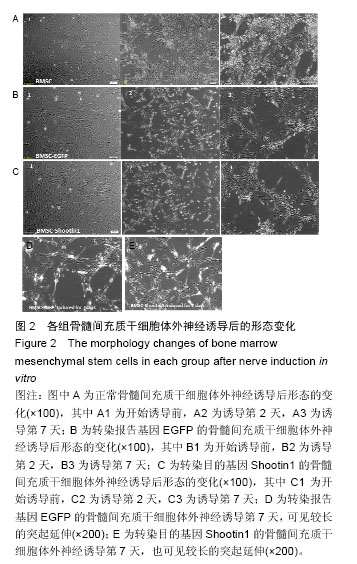

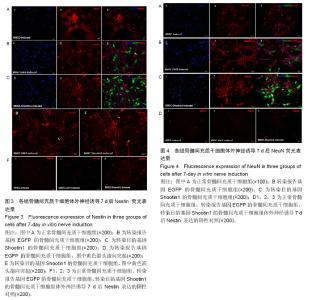

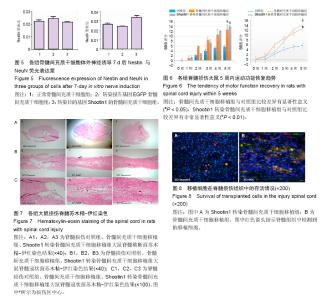

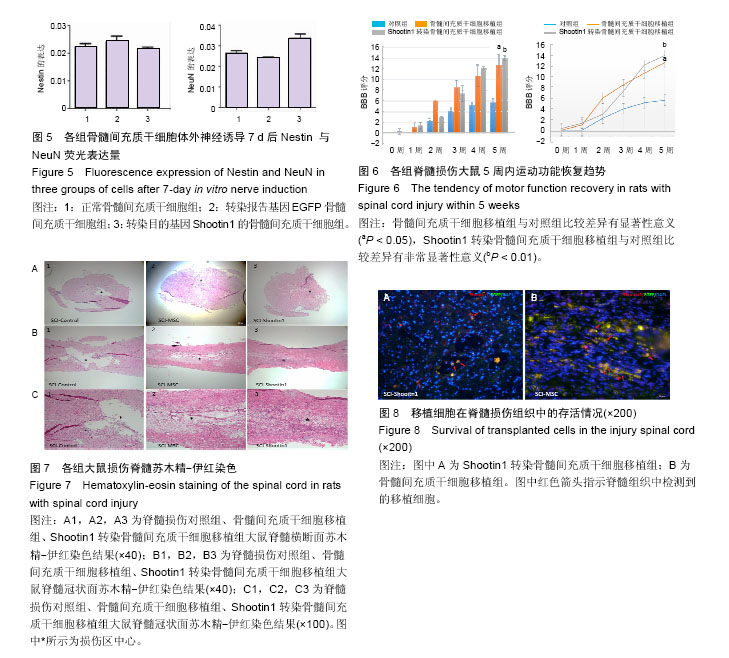

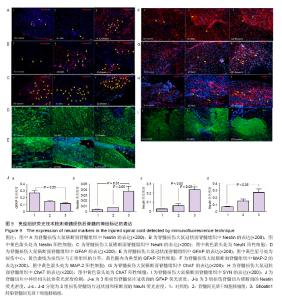

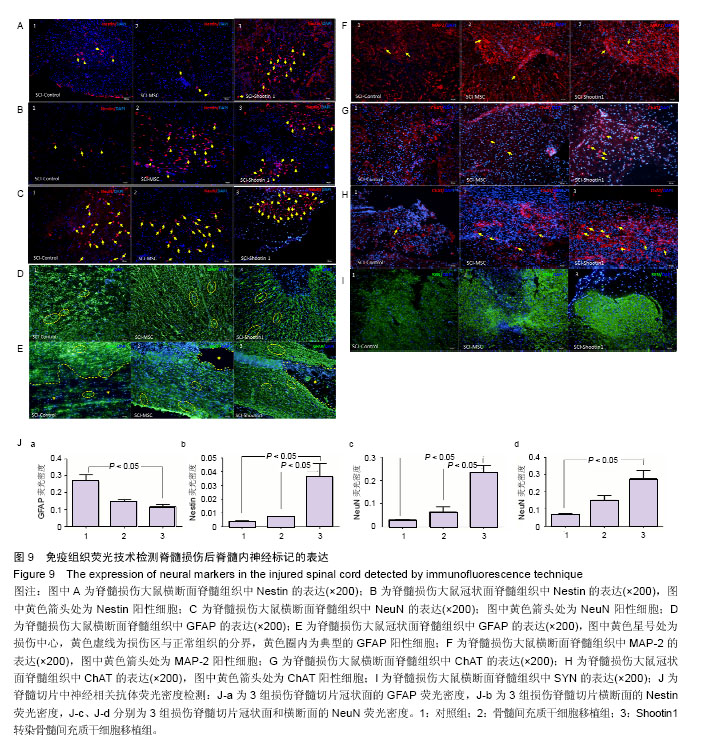

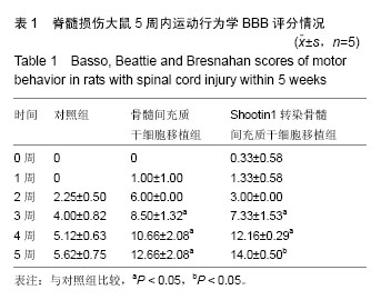

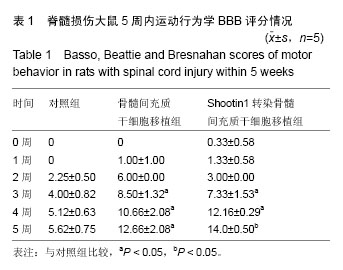

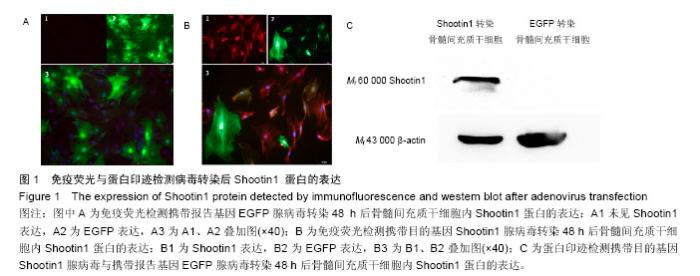

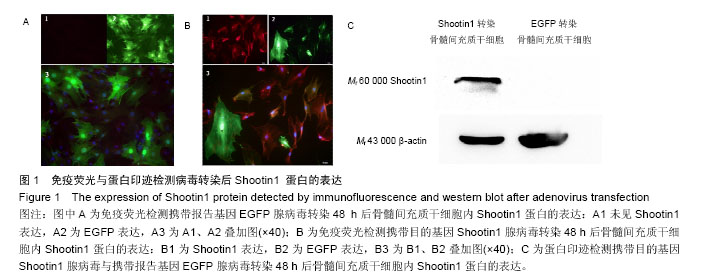

2.1 Shootin1转染骨髓间充质干细胞 用携带Shootin1腺病毒与EGFP对照病毒感染骨髓间充质干细胞2 d,出现大量绿色荧光,感染效率可达70%-80%,说明MOI=100可得到较高转染率的细胞。 2.2 免疫荧光与蛋白印迹检测病毒转染后Shootin1 蛋白的表达 图1B显示的是转染目的基因Shootin1- EGFP腺病毒的骨髓间充质干细胞中Shootin1蛋白表达,图1B1中检测到较强的Shootin1荧光信号,且与图1B2中EGFP荧光信号几乎共定位(图1B3),与对照组(图1A)相比,几乎所有骨髓间充质干细胞均成功转染上目的基因Shootin1,细胞内伴随有Shootin1蛋白的表达。蛋白印迹检测同样可见携带目的基因Shootin1的腺病毒成功转染骨髓间充质干细胞。图1C显示成功转染Shootin1基因的骨髓间充质干细胞中Shootin1蛋白的表达,转染目的基因Shootin1的骨髓间充质干细胞在Mr 60 000处出现一条明显的条带,而仅转染报告基因EGFP的骨髓间充质干细胞中未在Mr 60 000处出现条带。 2.3 骨髓间充质干细胞体外神经诱导与免疫荧光检测神经标记的表达 图2A-C显示的是3组不同类型的骨髓间充质干细胞体外经过神经诱导7 d后的形态变化。图2A为正常骨髓间充质干细胞组经过神经诱导后细胞形态变化图,该组细胞经过诱导后数量轻微减少,少许细胞形态变为细长形。图2B为转染报告基因EGFP的骨髓间充质干细胞组经诱导后大量减少,且多数细胞呈现椎形样,出现细长突起样延伸,细胞与细胞间类似发生了联系,诱导7 d后细胞突起样长度较正常骨髓间充质干细胞组长(图2D)。图2C为转染目的基因Shootin1的骨髓间充质干细胞组,该组细胞形态与转染报告基因EGFP的骨髓间充质干细胞组出现相同的变化,同时细胞数量减少,且出现较明显的突起样延伸(图2E)。 尽管神经诱导后细胞形态发生了较明显的变化,但仍不能说明细胞形态改变是由诱导剂中添加的化学因子引起的。于是进行了免疫荧光技术检测诱导后细胞中是否表达了神经相关标记。图3A-C为各组骨髓间充质干细胞诱导7 d后Nestin的表达情况。在图3B3、C3中出现的细胞突起样延伸,用免疫荧光技术可在这类细胞突起延伸端检测到明显的荧光信号(图3D和E黄色箭头处),而在正常骨髓间充质干细胞组中未发现突起样处有荧光信号,而少数形态未发生太大变化的细胞内可检测到荧光信号。 Nestin蛋白的表达能说明体外神经诱导骨髓间充质干细胞已向神经前体细胞分化,随后对体外神经诱导分化后NeuN蛋白表达进行免疫荧光检测,图4A-C为各组骨髓间充质干细胞诱导7 d后NeuN的表达情况。3组均发现NeuN蛋白的表达,且该蛋白主要表达于细胞核内,说明通过体外神经诱导,骨髓间充质干细胞大多数已成功分化为成熟的神经元。 免疫荧光检测3组细胞体外神经诱导7 d后Nestin 与NeuN荧光表达量,利用Image J2.0对荧光强度进行分析,可知3组Nestin与NeuN表达差异无显著性意义 (P > 0.05,图5)。 2.4 骨髓间充质干细胞移植治疗脊髓损伤运动行为学评价 表1是跟踪5周内脊髓损伤大鼠运动行为学BBB评分情况,脊髓损伤开始0-1周内,3组大鼠运动功能恢复情况差别不大。第4周开始2个细胞移植组大鼠的运动功能恢复情况均较对照组有明显提高。到达第5周,对照组大鼠运动功能恢复仅停留在5.62分左右,而2个细胞移植大鼠的运动功能恢复均达到10分以上。图6显示了5周内脊髓损伤大鼠运动功能恢复趋势,3组大鼠运动功能均有恢复提高,对照组大鼠恢复速率从第4周开始进入平台期,停留于5至6分,进一步运功功能恢复有限。5周内2个细胞移植组大鼠运动功能呈直线上升趋势,5周时均达到10分以上,为对照组的2倍。统计学分析显示骨髓间充质干细胞移植组BBB评分与对照组比较差异有显著性意义(P < 0.05),Shootin1转染骨髓间充质干细胞移植组BBB评分与对照组比较差异有非常显著性意义(P < 0.01),而Shootin1转染骨髓间充质干细胞移植组BBB评分与骨髓间充质干细胞移植组比较差异无显著性意义(P > 0.05),在此仅能说明细胞移植对于脊髓损伤具有治疗作用,而Shootin1转染骨髓间充质干细胞与未转染骨髓间充质干细胞移植的治疗效果差异不大。 2.5 脊髓损伤后脊髓组织内部结构的变化情况 图7A为治疗5周后3组大鼠脊髓横断面的苏木精-伊红染色结果。图7B,C为治疗5周后3组大鼠脊髓冠状面的苏木精-伊红染色结果。 脊髓组织切片苏木精-伊红染色结果显示,2个细胞移植组脊髓组织结构均较清晰,白质部分保持完整,灰质中有较小坏死区形成的空洞,瘢痕组织较少,但仍见灰质中组织结构较紊乱,细胞排列不整齐。对照组冠状面切片可见灰质几乎全部被破坏溶解,并形成巨大的空腔,瘢痕组织形成比细胞移植组增多,完整的细胞结构较少,其白质区较细胞移植组范围窄,结构较紊乱。同时发现对照组脊髓组织内细胞数目较细胞移植治疗组偏少。 2.6 免疫组织荧光技术检测脊髓损伤后脊髓内神经标记的表达情况 图8显示的是2个细胞移植组脊髓组织中检测到外源移植细胞的荧光信号,移植细胞的数量均较少。 检测到的外源移植细胞一方面会对损伤脊髓起到修复作用,另一方面大鼠自身也会对外源损伤产生神经修复功能。实验通过检测损伤治疗后第5周6个神经细胞相关标记来说明大鼠脊髓损伤后生理生化功能恢复情况(图9)。 在骨髓间充质干细胞移植组与Shootin1转染骨髓间充质干细胞移植组中可见Nestin表达明显增加,通过对损伤脊髓切片横断面的Nestin荧光强度统计分析可知,Shootin1转染骨髓间充质干细胞移植组与对照组比较差异有显著性意义(0.01 < P < 0.05),Shootin1转染骨髓间充质干细胞移植组与骨髓间充质干细胞移植组比较差异也有显著性意义(0.01 < P < 0.05)。 免疫荧光检测脊髓组织NeuN神经元特异性核蛋白表达的结果显示,Shootin1转染骨髓间充质干细胞移植组NeuN的表达量也较对照组与骨髓间充质干细胞移植组高,统计学分析可知,Shootin1转染骨髓间充质干细胞移植组损伤脊髓切片无论是冠状面还是横断面的NeuN荧光密度均较对照组差异有显著性意义(0.01 < P < 0.05),同时Shootin1转染骨髓间充质干细胞移植组与骨髓间充质干细胞移植组比较差异也有显著性意义(0.01 < P < 0.05)。该结果说明了在Shootin1转染骨髓间充质干细胞移植组中存在大量成熟的神经元细胞。 免疫荧光检测脊髓组织GFAP表达的结果显示,2个细胞移植组较对照组GFAP表达量增加,且Shootin1转染骨髓间充质干细胞移植组最高。对3组损伤脊髓切片冠状面的GFAP荧光密度分析可知,Shootin1转染骨髓间充质干细胞移植组与骨髓间充质干细胞移植组比较差异有显著性意义(0.01 < P < 0.05)。 免疫荧光检测脊髓组织MAP-2表达的结果显示,2个细胞移植组较对照组均有MAP-2表达量的提高,2个细胞移植组SYN表达的荧光信号均较对照组强,可说明2个细胞移植组中的神经元细胞突触功能恢复情况较好。 通过对3组损伤脊髓切片进行神经相关抗体免疫荧光染色与统计学分析,Shootin1转染骨髓间充质干细胞移植组对比对照组只有在Nestin、NeuN、GFAP 3种神经蛋白表达上有明显的差异,Nestin、NeuN数量的增多说明脊髓损伤后的运动功能修复程度较高,对照组GFAP增粗胞体变大,是损伤后胶质增生的表现,而Shootin1转染骨髓间充质干细胞移植组GFAP荧光表达量较对照组低。Shootin1转染骨髓间充质干细胞移植组与骨髓间充质干细胞移植组间差异无显著性意义,暂未有充分证据证明Shootin1蛋白对脊髓修复具有明显作用。"

| [1] Toriyama M, Shimada T, Kim KB, et al. Shootin1: A protein involved in the organization of an asymmetric signal for neuronal polarization. J Cell Biol. 2006; 175(1):147-157.[2] Toriyama M, Sakumura Y, Shimada T, et al. A diffusion-based neurite length-sensing mechanism involved in neuronal symmetry breaking. Mol Syst Biol. 2010;6:394.[3] Prockop DJ. Marrow stromal cells as stem cells for nonhematopoietic tissues. Science. 1997;276(5309): 71-74.[4] Barzilay R, Kan I, Ben-Zur T, et al. Induction of human mesenchymal stem cells into dopamine-producing cells with different differentiation protocols. Stem Cells Dev. 2008;17(3):547-554.[5] 乔晓峰,杨建华,朱光宇,等.脊髓损伤模型的制备及其评价[J].中国全科医学,2009,12(14):1279-1281.[6] Allen AR. Surgery of experimental lesions of spinal cord equivalent to crush injury of fracture dislocation of spinal column. JAMA. 1911;57(10):878-880.[7] Basso DM, Beattie MS, Bresnahan JC. Graded histological and locomotor outcomes after spinal cord contusion using the NYU weight-drop device versus transection. Exp Neurol. 1996;139(2):244-256.[8] Thomas AJ, Nockels RP, Pan HQ, et al. Progesterone is neuroprotective after acute experimental spinal cord trauma in rats. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1999;24(20): 2134-2138.[9] Metz GA, Curt A, van de Meent H, et al. Validation of the weight-drop contusion model in rats: a comparative study of human spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2000; 17(1):1-17.[10] Mahmood A, Lu D, Yi L, et al. Intracranial bone marrow transplantation after traumatic brain injury improving functional outcome in adult rats. J Neurosurg. 2001; 94(4):589-595.[11] Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, et al. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284(5411):143-147.[12] Ciccolini F, Svendsen CN. Fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2) promotes acquisition of epidermal growth factor (EGF) responsiveness in mouse striatal precursor cells: identification of neural precursors responding to both EGF and FGF-2. J Neurosci. 1998;18(19):7869-7880.[13] Toriyama M, Shimada T, Kim KB, et al. Shootin1: A protein involved in the organization of an asymmetric signal for neuronal polarization. J Cell Biol. 2006; 175(1):147-157.[14] Sapir T, Levy T, Sakakibara A, et al. Shootin1 acts in concert with KIF20B to promote polarization of migrating neurons. J Neurosci. 2013;33(29): 11932-11948.[15] Hirokawa N, Noda Y, Tanaka Y, et al. Kinesin superfamily motor proteins and intracellular transport. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10(10):682-696.[16] Horiguchi K, Hanada T, Fukui Y, et al. Transport of PIP3 by GAKIN, a kinesin-3 family protein, regulates neuronal cell polarity. J Cell Biol. 2006;174(3):425-436.[17] Falnikar A, Tole S, Baas PW. Kinesin-5, a mitotic microtubule-associated motor protein, modulates neuronal migration. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22(9): 1561-1574.[18] Westendorf JM, Rao PN, Gerace L. Cloning of cDNAs for M-phase phosphoproteins recognized by the MPM2 monoclonal antibody and determination of the phosphorylated epitope. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(2):714-718.[19] Abaza A, Soleilhac JM, Westendorf J, et al. M phase phosphoprotein 1 is a human plus-end-directed kinesin-related protein required for cytokinesis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(30):27844-27852.[20] Fritzler MJ, Kerfoot SM, Feasby TE, et al. Autoantibodies from patients with idiopathic ataxia bind to M-phase phosphoprotein-1 (MPP1). J Investig Med. 2000;48(1):28-39.[21] Miki H, Okada Y, Hirokawa N. Analysis of the kinesin superfamily: insights into structure and function. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15(9):467-476. |

| [1] | Zhang Tongtong, Wang Zhonghua, Wen Jie, Song Yuxin, Liu Lin. Application of three-dimensional printing model in surgical resection and reconstruction of cervical tumor [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(9): 1335-1339. |

| [2] | Hou Jingying, Yu Menglei, Guo Tianzhu, Long Huibao, Wu Hao. Hypoxia preconditioning promotes bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells survival and vascularization through the activation of HIF-1α/MALAT1/VEGFA pathway [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 985-990. |

| [3] | Liang Xueqi, Guo Lijiao, Chen Hejie, Wu Jie, Sun Yaqi, Xing Zhikun, Zou Hailiang, Chen Xueling, Wu Xiangwei. Alveolar echinococcosis protoscolices inhibits the differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells into fibroblasts [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 996-1001. |

| [4] | Geng Yao, Yin Zhiliang, Li Xingping, Xiao Dongqin, Hou Weiguang. Role of hsa-miRNA-223-3p in regulating osteogenic differentiation of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 1008-1013. |

| [5] | Lun Zhigang, Jin Jing, Wang Tianyan, Li Aimin. Effect of peroxiredoxin 6 on proliferation and differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells into neural lineage in vitro [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 1014-1018. |

| [6] | Zhu Xuefen, Huang Cheng, Ding Jian, Dai Yongping, Liu Yuanbing, Le Lixiang, Wang Liangliang, Yang Jiandong. Mechanism of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells differentiation into functional neurons induced by glial cell line derived neurotrophic factor [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 1019-1025. |

| [7] | Pei Lili, Sun Guicai, Wang Di. Salvianolic acid B inhibits oxidative damage of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and promotes differentiation into cardiomyocytes [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 1032-1036. |

| [8] | Wan Ran, Shi Xu, Liu Jingsong, Wang Yansong. Research progress in the treatment of spinal cord injury with mesenchymal stem cell secretome [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 1088-1095. |

| [9] | Wang Shiqi, Zhang Jinsheng. Effects of Chinese medicine on proliferation, differentiation and aging of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells regulating ischemia-hypoxia microenvironment [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 1129-1134. |

| [10] | Zeng Yanhua, Hao Yanlei. In vitro culture and purification of Schwann cells: a systematic review [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 1135-1141. |

| [11] | Xu Dongzi, Zhang Ting, Ouyang Zhaolian. The global competitive situation of cardiac tissue engineering based on patent analysis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(5): 807-812. |

| [12] | Chen Junyi, Wang Ning, Peng Chengfei, Zhu Lunjing, Duan Jiangtao, Wang Ye, Bei Chaoyong. Decalcified bone matrix and lentivirus-mediated silencing of P75 neurotrophin receptor transfected bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells to construct tissue-engineered bone [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(4): 510-515. |

| [13] | Wu Zijian, Hu Zhaoduan, Xie Youqiong, Wang Feng, Li Jia, Li Bocun, Cai Guowei, Peng Rui. Three-dimensional printing technology and bone tissue engineering research: literature metrology and visual analysis of research hotspots [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(4): 564-569. |

| [14] | Chang Wenliao, Zhao Jie, Sun Xiaoliang, Wang Kun, Wu Guofeng, Zhou Jian, Li Shuxiang, Sun Han. Material selection, theoretical design and biomimetic function of artificial periosteum [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(4): 600-606. |

| [15] | Liu Fei, Cui Yutao, Liu He. Advantages and problems of local antibiotic delivery system in the treatment of osteomyelitis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(4): 614-620. |

| Viewed | ||||||

|

Full text |

|

|||||

|

Abstract |

|

|||||