Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research ›› 2022, Vol. 26 ›› Issue (19): 3095-3099.doi: 10.12307/2022.392

Previous Articles Next Articles

Prospects and clinical transformation value on the application of dental follicle stem cells in the regeneration and repair of teeth and periodontal tissue

Meng Shengzi, Liu Rong, Luo Yaxin, Bi Haoran, Chen Xiaoxu, Yang Kun

- Department of Periodontology, Hospital of Stomatology, Zunyi Medical University, Zunyi 563000, Guizhou Province, China

-

Received:2021-03-10Revised:2021-04-15Accepted:2021-07-22Online:2022-07-08Published:2021-12-29 -

Contact:Yang Kun, MD, Associate professor, Department of Periodontology, Hospital of Stomatology, Zunyi Medical University, Zunyi 563000, Guizhou Province, China -

About author:Meng Shengzi, Master candidate, Department of Periodontology, Hospital of Stomatology, Zunyi Medical University, Zunyi 563000, Guizhou Province, China -

Supported by:the National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 81760199 (to YK); the National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 81860196 (to YK); the Science and Technology Fund of Guizhou Province, No. [2020]1Y328 (to YK)

CLC Number:

Cite this article

Meng Shengzi, Liu Rong, Luo Yaxin, Bi Haoran, Chen Xiaoxu, Yang Kun. Prospects and clinical transformation value on the application of dental follicle stem cells in the regeneration and repair of teeth and periodontal tissue[J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(19): 3095-3099.

share this article

Add to citation manager EndNote|Reference Manager|ProCite|BibTeX|RefWorks

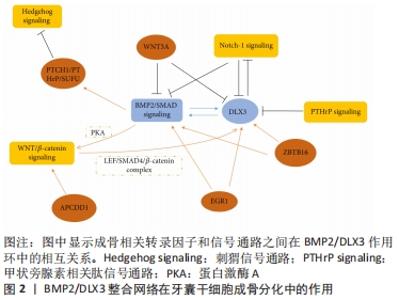

2.1.1 牙囊干细胞表面标志物 牙囊干细胞呈长梭形,类似成纤维细胞的形态;可从尚未长出的第三磨牙的牙囊组织中分离提取出来,其具有较高的细胞增殖率;经特定的冷冻保存剂可长期稳定保存[5]。研究表明,在轻度热应激的条件下,即保持39 ℃或40 ℃的培养温度,可有效促进其成骨分化以及增殖[6],这一发现将有利于制定适宜的培养条件并用于加快牙囊干细胞的体外扩增与分化。牙囊干细胞具有间充质干细胞的表型特征,常见的表面标志物如表达低水平的CD34[7]、CD44、CD90、CD105、CD45、CD31和高水平的CD29,而HLA-DR、TEP-1、SOX-2和OCT-4呈阳性表达[8];LIMA等[9]通过实验发现牙囊干细胞群不仅表达胚胎干细胞、间充质干细胞标志,而且有p75(50%)、HNK1(< 10%)和少量胶质纤维酸性蛋白阳性细胞(< 20%),这也是首次发现在牙囊中存在神经干细胞和胶质样细胞的研究。此外,牙囊细胞还表达牙周膜和牙骨质标志物[10],如牙骨质蛋白1、牙周膜相关蛋白1、成纤维细胞生长因子2以及牙周膜相关蛋白1。高表达的Noch-1在牙囊细胞发育过程中起重要作用,Noch-1信号通过调节细胞周期和端粒酶活性而促进其自我更新和增殖[11]。相对于牙周膜干细胞,牙囊干细胞显示出更出色的抗氧化防御能力[7],在比较牙囊前体细胞和牙周膜干细胞的骨形成相关基因甲基化特征时,后者显示出更高的成骨相关因子转录水平以及更多的体内新骨形成[12]。 2.1.2 牙囊干细胞多向分化潜能 牙囊干细胞具有成骨、成牙骨质、成脂肪和成神经等分化潜能。当在适宜的培养条件下,其具有较强的成骨能力,成骨分化细胞在体外形成矿化结节,成骨标志物Runt相关转录因子2、Ⅰ型胶原和碱性磷酸酶等显著增加[13],且在培养时使用软质的弹性基质可更支持其成骨分化[14]。BMP、Noch、Hedgehog、WNT等成骨相关通路,对牙囊干细胞的调控可通过BMP2/DLX3整合环来实现,见图2[15]。"

Wnt信号在间充质干细胞的增殖分化与迁移归巢中扮演着重要角色,经典的Wnt通路抑制牙囊干细胞成骨分化过程,而β-连环蛋白通过激活蛋白激酶A来支持BMP2/DLX3介导的成骨分化[16]。Wnt5a显著增加了RANK配体依赖的破骨细胞分化,并可能参与牙槽骨再生或吸收[17];研究指出在牙囊干细胞中存在由ZBTB16调控的非依赖性Runt相关转录因子2成骨分化机制[18],ZBTB16诱导牙囊干细胞晚期成骨分化标志物的表达,但不诱导Runt相关转录因子2和碱性磷酸酶的表达[19];有研究检测成骨分化过程中差异表达的circRNAs,发现circFgfr2在成骨分化过程中起正调节作用,miR-133表达下降,而Bmp6表达升高[20]。另外,在dNCPs/DFCCM处理的牙囊干细胞中,可发现高表达的矿化相关标志物以及成牙骨质细胞系特异性标志物[21],即这些细胞沿成牙骨质细胞谱系分化。 来源于颅神经嵴的牙囊干细胞可能是神经组织工程的种子细胞,具有修复脊髓全横断损伤和促进功能恢复的潜能[22]。多年来学者们对牙囊干细胞衍生的神经谱系的研究相对较少,YANG等[23]对比不同细胞在不同神经诱导分化方式下神经标志物基因的表达,发现用神经培养基、表皮生长因子和碱性成纤维细胞生长因子培养后的神经分化潜能更高;但目前的研究缺乏神经分化细胞的具体功能评估。在2017年,XU等[24]研究表明人牙囊来源上皮细胞在体外三维诱导条件下能分化为唾液腺腺泡细胞和导管细胞,将其负载于脱细胞大鼠腮腺支架,移植到裸鼠肾包膜中可以向涎腺样细胞分化。除此之外,有报道称牙囊干细胞可诱导分化为功能性肝细胞,并有某些肝细胞功能[25];也可通过STAT3信号通路调控肝细胞生长因子受体表达并促进其向肝细胞分化和发育成熟[26]。 总的来说,在多种因素的影响下牙囊干细胞具有丰富的分化潜能。尽管如此,仍需不断探索牙囊干细胞定向分化的调控机制以提高其实用性与可控性。 2.1.3 牙囊干细胞的其他特性 牙囊干细胞除了其本身显著的再生潜能以外,在免疫调控与治疗方面也有着不可或缺的作用。牙囊干细胞移植后与细胞外基质相互作用,能控制炎症或排斥反应。牙源性间充质干细胞的免疫调控方式包括抗炎和促炎两个方面[27]。有学者利用MuSK免疫小鼠经静脉注射牙囊干细胞,结果显示小鼠的实验性自身免疫性重症肌无力的发生受到抑制,疾病严重程度也降低,血清内抗Musk抗体、NMJ、IgG、C3沉积水平和CD11b+淋巴细胞均显著降低[28],并表明牙囊干细胞主要抑制机体天然免疫系统从而发挥作用。牙囊干细胞还在一定程度上保护肠道组织,TOPCU SARICA等[29]构建盲肠结扎穿孔诱导的脓毒症小鼠模型,局部注射牙囊干细胞通过降低肿瘤坏死因子α和增加Treg细胞比例来控制肠道组织的炎症反应。 有学者发现牙囊干细胞抑制了哮喘患者的CD4+T淋巴细胞的增殖反应,增加Treg细胞比例,通过吲哚胺2,3-双氧酶和转化生长因子β途径降低白细胞介素4、GATA结合蛋白3的表达,并上调干扰素γ、T-bet和白细胞介素10的表达[30],可见牙囊干细胞与其分泌因子相互作用于各种炎症环境发挥其免疫调控功能,提示其有望用于某些免疫以及炎症性疾病的治疗。 牙囊细胞的组织工程应用不仅体现在促进口腔颌面部软硬组织的重建,而且对神经或其他组织损伤也显示出应用前景,LI等[31]将人牙囊细胞结合于聚己内酯/聚乳酸-羟基乙酸共聚物材料修复小鼠脊髓缺损,结果发现其促进了髓鞘再分化的少突胶质细胞系标志物Olig2的表达。在2016年,SUNG等[32]尝试用琥珀酰苯胺异羟肟酸(SAHA)诱导的方法,将其加入体外牙囊干细胞培养基中,结果成功诱导其向心肌细胞分化,且将诱导的心肌细胞注射入动物体内,可在心脏内稳定生存,且炎症反应轻微,这表明牙囊干细胞也有治疗某些心脏疾病的潜力。 2.2 牙囊干细胞与牙及牙周组织再生修复 "

2.2.1 牙本质及牙髓的再生修复 局部病变可导致牙髓功能丧失或整个牙齿的缺失,目前传统的牙髓治疗手段以及常规义齿修复方式都难以恢复患者天然牙原本的生理功能,随着组织工程的高速发展,逐渐为牙本质和牙髓再生提供了可能。 首先,HONG等[33]观察大鼠牙囊干细胞条件培养液对脂多糖诱导的大鼠牙髓炎症细胞的炎症控制作用时,发现该条件培养基通过下调ERK1/2和NF-κB信号通路,抑制促炎性细胞因子白细胞介素1β、白细胞介素6和肿瘤坏死因子α的表达,而促进白细胞介素4和转化生长因子β的表达,由此可利于牙髓的修复。人牙本质基质可结合牙囊干细胞用于牙本质及牙髓的再生,LI等[34]发现与磷酸钙组相比,牙囊干细胞在人牙本质基质上黏附生长,表现出良好的生物相容性,并可在免疫缺陷小鼠背部诱导并支持完整牙本质组织的再生,经检测有牙本质标志物牙本质涎蛋白和牙本质基质蛋白1的表达。同样有学者报道,相较于牙周膜干细胞,牙囊干细胞表现出更强的增殖能力和分化潜能,经牙本质基质支架诱导并移植入小鼠背部皮下,牙囊干细胞则显示出更显著的牙本质形成能力[35]。在此过程中,如利用抗氧化剂叔丁基对苯二酚处理同种异体牙囊干细胞复合的异种牙本质基质支架,可在一定程度上减少牙本质再生过程中破骨细胞的生成与吸收[36]。此外,低温保存的牙本质基质也可以为牙囊干细胞再生牙本质组织提供良好的生物支架和稳定的诱导微环境,这主要因为其孔径较大,搭载细胞时能释放更多的牙本质形成相关蛋白,诱导过程也可形成如牙本质小管、前牙本质、胶原纤维等组织[37]。 牙根承载咬合力及维持着牙齿整体功能稳定,而牙本质作为牙齿的重要支撑结构,再生出牙本质组织对生物牙根再生至关重要。YANG等[38]将牙囊干细胞复合牙本质基质植入小鼠背部皮下,发现形成新的牙本质牙髓样组织和牙骨质牙周复合体,且新形成的组织中Ⅰ型胶原、巢蛋白和Ⅷ因子、牙本质涎蛋白和牙骨质附着蛋白等标志物呈阳性表达,表明成功再生出牙本质及牙根样组织。此外,GUO等[39]将牙囊细胞联合牙本质基质植入牙槽窝4周后,发现有牙髓及牙周组织表面标记物染色阳性的根状组织再生,提示牙囊细胞与牙本质基质的联合应用对牙根再生治疗的重要意义;此后,将上述二者结合进行异种生物牙根动物模型实验表明,促炎症细胞因子白细胞介素6及转化生长因子β的基因表达均有不同程度降低(P < 0.01),而且相比对照组,植入4周后抗酒石酸酸性磷酸酶染色阳性的破骨细胞明显减少,说明细胞发挥免疫调节作用有利于局部牙本质的再生[40]。 为构建合适的微环境,研究者们考虑将多种生物材料制剂、三维细胞培养等技术应用于牙本质再生[41],但需要更深入的研究以获得更理想的效果。如何保证牙囊干细胞介导新形成的牙本质拥有充足的血液供应和神经支配等问题仍需要进一步解决,作为种子细胞之一的牙囊干细胞值得学者们深入研究与探讨。 2.2.2 牙槽骨的再生修复 多种诱因包括发育畸形、炎症、创伤、颌骨及软组织肿瘤等,可导致牙槽骨缺损,进而影响患者咀嚼、吞咽、言语表达等正常生理功能,影响生活质量。目前学者们利用干细胞移植的方式无疑为修复牙槽骨缺损提供了全新的方向。 牙囊干细胞联合其他细胞可充分利用组织工程的优势,有学者通过牙髓干细胞与牙囊干细胞共培养结合动物模型研究,证明牙髓干细胞可促进牙囊干细胞的成骨细胞分化和抑制破骨细胞的生成,表现为骨形态发生蛋白2、骨涎蛋白、骨钙素等成骨相关基因的表达水平明显升高,而核因子κB受体活化因子配体表达降低[42];而且在赫特维希上皮根鞘细胞和牙髓干细胞同时存在的情况下,可在动物体内将牙囊干细胞定向分化为成骨或成牙骨质细胞[43],这为再生牙槽骨提供了新思路。对于牙源性间充质干细胞而言,通常需要结合细胞支架材料才能在组织内更好的黏附增殖与高效成骨;研究者们根据牙囊干细胞的特性选用了多种类型的支架材料,利用明胶海绵在三维结构下培养牙囊干细胞[44], 在移植入免疫缺陷大鼠颅顶之后,相比对照组,未加地塞米松成骨诱导的牙囊干细胞移植后骨质量和骨密度(P=0.039)、骨矿含量(P=0.006)、骨体积(P=0.002),骨矿含量/总容积(P=0.006),骨体积/总容积(P=0.002)均明显增高。与此同时,有学者发现在体外培养条件下,与对照组相比,牙囊细胞在磷酸三钙培养基上有较强的细胞黏附与增殖能力,且磷酸三钙可刺激成骨分化,成骨细胞标志物骨涎蛋白高度表达,而标准培养基中分化的牙囊细胞则几乎不表达[45]。磷酸三钙虽然会诱导牙囊细胞凋亡,但同时也刺激了牙囊细胞抗凋亡基因的表达和成骨分化标志物的表达[46],这可能不会损害细胞的增殖和成骨分化能力。 近年来纳米材料在骨再生领域中表现出重要作用,其中纳米羟基磷灰石/纤维素支架促进人牙囊细胞的黏附增殖[47],且无细胞毒性;氧化石墨烯以及氮掺杂石墨烯纳米材料也有良好的效果[48],具体表现在对人牙囊干细胞毒性较低和对线粒体损伤小,后者在低质量浓度(4 mg/L)时表现出良好抗氧化能力以及安全性。牙囊干细胞结合聚己内酯支架修复免疫抑制小鼠颅骨缺损,通过断层扫描和组织学分析,可观察到骨再生,而未移植的空白对照组未观察到骨再生[49]。 与此同时,牙囊干细胞也有望用于促进牙种植体表面的骨再生;有体外实验研究表明牙囊干细胞具有自发的成骨分化倾向,相比对照组,黏附增殖于羟基磷灰石涂层钛种植体的牙囊干细胞具有最佳的持续矿化状态,且更有利于牙囊细胞获得更成熟的成骨细胞表型[50]。 2.2.3 牙周组织的再生修复 牙周病是全球性的流行性疾病,影响患者自身的牙支持结构,可导致牙的松动脱落并导致全身性炎症[51]。近年来干细胞生物学和材料学得到飞速发展,通过移植干细胞的方式,有望实现牙周组织真正意义上的再生,即形成具有复杂解剖结构的牙周复合体[52]。牙囊是牙周组织发育前体的重要组成部分,而来源于牙胚发育期的牙囊干细胞或许能成为牙周组织再生的首选种子细胞。 利用牙囊干细胞进行牙周组织再生的相关研究已经较为深入而广泛。有学者研究发现赫特维希上皮根鞘细胞与牙囊细胞共培养后,骨涎蛋白、骨桥蛋白、Ⅰ型胶原、Ⅲ型胶原等相关mRNA表达显著高于细胞单纯培养组,且植入大鼠大网膜之后,形成了牙骨质和牙周膜样组织[53]。GUO等[54]分离出人阻生磨牙的牙囊细胞,将不同亚克隆牙囊细胞混合陶瓷牛骨后植入裸鼠皮下口袋,在植入6周后观察到了牙骨质-牙周膜复合体的形成。GUO等[55]研究者通过比较牙囊细胞和牙周膜干细胞两种细胞片在体内的生物活性,前者的层粘连蛋白、纤维连接蛋白以及成骨相关基因骨涎蛋白、骨钙素和骨桥蛋白表达显著强于牙周膜干细胞,提示牙囊细胞片具有更强的牙周再生潜能;该作者进一步比较经脂多糖诱导的牙囊干细胞和牙周膜干细胞膜片在移植入实验性犬牙周炎缺损模型的表现,结果只有牙囊细胞片组才能观察到完整的牙周再生,包括牙骨质-牙周膜复合体结构,且形成了更多的牙槽骨[56]。人牙囊细胞片负载于携带罗格列酮的异种天然脱细胞基质[57],还可通过特定途径促进巨噬细胞极化,有效提高异种脱细胞生物材料组织的移植存活率,为软硬界面的再生及其与调控宿主免疫反应的有效结合提供了参考。 NIVEDHITHA SUNDARAM等[58]开发了由聚己内酯多尺度电纺膜和壳聚糖/2%CaSO4支架组成的双层结构,可促进蛋白质吸附,并促进人牙囊细胞成骨和成纤维细胞分化。SOWMYA等[59]采用特异性多孔三层纳米复合水凝胶支架联合人牙囊细胞,植入兔上颌骨牙周缺损模型内,与其他对照组相比,含生长因子的上述支架在缺损处形成完全愈合的状态,形成了新的牙槽骨、牙骨质以及牙周膜组织。另外,LI等[60]利用猪牙本质基质与同种异体牙囊干细胞相结合构建生物牙根,在移植恒河猴颌骨6个月后, 可见伴有巨噬细胞极化的牙周膜样纤维生长到周围的牙槽骨中,且Ⅰ型胶原、骨膜蛋白、βⅢ微管蛋白表达阳性,这有助于牙骨质与牙槽骨改建的整合。YANG等[61]将人牙囊干细胞片和人牙本质基质颗粒植入Beagle犬单壁牙周骨缺损模型中,放射学和组织学分析均显示牙周组织的再生效果优于对照组,且在一定程度上实现了典型“三明治”结构的再生。 由此可见,在牙周炎局部的炎症微环境中,牙囊细胞表现出靶向炎症反应的同时促进牙周组织再生,这使得牙囊细胞成为良好的干细胞来源,但牙囊细胞在牙周组织内的再生效果需要更多研究验证并长期观察评估,也正因牙周组织结构的复杂性以及再生微环境的不可控因素,需深入了解炎症微环境影响牙囊细胞的作用机制,以期获得更佳的修复效果。"

| [1] ZHAI Q, DONG Z, WANG W, et al. Dental stem cell and dental tissue regeneration. Front Med. 2019;13(2):152-159. [2] YANG X, MA Y, GUO W, et al. Stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth as an alternative cell source in bio-root regeneration. Theranostics. 2019;9(9):2694-2711. [3] SALGADO CL, BARRIAS CC, MONTEIRO FJM. Clarifying the Tooth-Derived Stem Cells Behavior in a 3D Biomimetic Scaffold for Bone Tissue Engineering Applications. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2020;8:724. [4] FENG G, WU Y, YU Y, et al. Periodontal ligament-like tissue regeneration with drilled porous decalcified dentin matrix sheet composite. Oral Dis. 2018;24(3):429-441. [5] PARK BW, JANG SJ, BYUN JH, et al. Cryopreservation of human dental follicle tissue for use as a resource of autologous mesenchymal stem cells. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2017;11(2):489-500. [6] REZAI RAD M, WISE GE, BROOKS H, et al. Activation of proliferation and differentiation of dental follicle stem cells (DFSCs) by heat stress. Cell Prolif. 2013;46(1):58-66. [7] LI J, LI H, TIAN Y, et al. Cytoskeletal binding proteins distinguish cultured dental follicle cells and periodontal ligament cells. Exp Cell Res. 2016; 345(1):6-16. [8] YILDIRIM S, ZIBANDEH N, GENC D, et al. The Comparison of the Immunologic Properties of Stem Cells Isolated from Human Exfoliated Deciduous Teeth, Dental Pulp, and Dental Follicles. Stem Cells Int. 2016; 2016:4682875. [9] LIMA RL, HOLANDA-AFONSO RC, MOURA-NETO V, et al. Human dental follicle cells express embryonic, mesenchymal and neural stem cells markers. Arch Oral Biol. 2017;73:121-128. [10] SOWMYA S, CHENNAZHI KP, ARZATE H, et al. Periodontal Specific Differentiation of Dental Follicle Stem Cells into Osteoblast, Fibroblast, and Cementoblast. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2015;21(10):1044-1058. [11] CHEN X, ZHANG T, SHI J, et al. Notch1 signaling regulates the proliferation and self-renewal of human dental follicle cells by modulating the G1/S phase transition and telomerase activity. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e69967. [12] AI T, ZHANG J, WANG X, et al. DNA methylation profile is associated with the osteogenic potential of three distinct human odontogenic stem cells. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2018;3:1. [13] MORI G, BALLINI A, CARBONE C, et al. Osteogenic differentiation of dental follicle stem cells. Int J Med Sci. 2012;9(6):480-487. [14] VIALE-BOURONCLE S, VÖLLNER F, MÖHL C, et al. Soft matrix supports osteogenic differentiation of human dental follicle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;410(3):587-592. [15] ZHOU T, PAN J, WU P, et al. Dental Follicle Cells: Roles in Development and Beyond. Stem Cells Int. 2019;2019:9159605. [16] VIALE-BOURONCLE S, KLINGELHÖFFER C, ETTL T, et al. A protein kinase A (PKA)/β-catenin pathway sustains the BMP2/DLX3-induced osteogenic differentiation in dental follicle cells (DFCs). Cell Signal. 2015;27(3):598-605. [17] XIANG L, CHEN M, HE L, et al. Wnt5a regulates dental follicle stem/progenitor cells of the periodontium. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2014;5(6):135. [18] FELTHAUS O, GOSAU M, KLEIN S, et al. Dexamethasone-related osteogenic differentiation of dental follicle cells depends on ZBTB16 but not Runx2. Cell Tissue Res. 2014;357(3):695-705. [19] FELTHAUS O, GOSAU M, MORSCZECK C. ZBTB16 induces osteogenic differentiation marker genes in dental follicle cells independent from RUNX2. J Periodontol. 2014;85(5):e144-151. [20] DU Y, LI J, HOU Y, et al. Alteration of circular RNA expression in rat dental follicle cells during osteogenic differentiation. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120(8):13289-13301. [21] WEN X, LIU L, DENG M, et al. In vitro cementoblast-like differentiation of postmigratory neural crest-derived p75(+) stem cells with dental follicle cell conditioned medium. Exp Cell Res. 2015;337(1):76-86. [22] YANG C, LI X, SUN L, et al. Potential of human dental stem cells in repairing the complete transection of rat spinal cord. J Neural Eng. 2017;14(2):026005. [23] YANG C, SUN L, LI X, et al. The potential of dental stem cells differentiating into neurogenic cell lineage after cultivation in different modes in vitro. Cell Reprogram. 2014;16(5):379-391. [24] XU QL, FURUHASHI A, ZHANG QZ, et al. Induction of Salivary Gland-Like Cells from Dental Follicle Epithelial Cells. J Dent Res. 2017;96(9):1035-1043. [25] PATIL R, KUMAR BM, LEE WJ, et al. Multilineage potential and proteomic profiling of human dental stem cells derived from a single donor. Exp Cell Res. 2014;320(1):92-107. [26] KUMAR A, KUMAR V, RATTAN V, et al. Molecular spectrum of secretome regulates the relative hepatogenic potential of mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow and dental tissue. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):15015. [27] ZHOU LL, LIU W, WU YM, et al. Oral Mesenchymal Stem/Progenitor Cells: The Immunomodulatory Masters. Stem Cells Int. 2020;2020: 1327405. [28] ULUSOY C, ZIBANDEH N, YILDIRIM S, et al. Dental follicle mesenchymal stem cell administration ameliorates muscle weakness in MuSK-immunized mice. J Neuroinflammation. 2015;12:231. [29] TOPCU SARICA L, ZIBANDEH N, GENÇ D, et al. Immunomodulatory and Tissue-preserving Effects of Human Dental Follicle Stem Cells in a Rat Cecal Ligation and Perforation Sepsis Model. Arch Med Res. 2020;51(5):397-405. [30] GENÇ D, ZIBANDEH N, NAIN E, et al. Dental follicle mesenchymal stem cells down-regulate Th2-mediated immune response in asthmatic patients mononuclear cells. Clin Exp Allergy. 2018;48(6):663-678. [31] LI X, YANG C, LI L, et al. A therapeutic strategy for spinal cord defect: human dental follicle cells combined with aligned PCL/PLGA electrospun material. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:197183. [32] SUNG IY, SON HN, ULLAH I, et al. Cardiomyogenic Differentiation of Human Dental Follicle-derived Stem Cells by Suberoylanilide Hydroxamic Acid and Their In Vivo Homing Property. Int J Med Sci. 2016;13(11):841-852. [33] HONG H, CHEN X, LI K, et al. Dental follicle stem cells rescue the regenerative capacity of inflamed rat dental pulp through a paracrine pathway. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;11(1):333. [34] LI R, GUO W, YANG B, et al. Human treated dentin matrix as a natural scaffold for complete human dentin tissue regeneration. Biomaterials. 2011;32(20):4525-4538. [35] TIAN Y, BAI D, GUO W, et al. Comparison of human dental follicle cells and human periodontal ligament cells for dentin tissue regeneration. Regen Med. 2015;10(4):461-479. [36] SUN J, LI J, LI H, et al. tBHQ Suppresses Osteoclastic Resorption in Xenogeneic-Treated Dentin Matrix-Based Scaffolds. Adv Healthc Mater. 2017;6(18):1700127. [37] JIAO L, XIE L, YANG B, et al. Cryopreserved dentin matrix as a scaffold material for dentin-pulp tissue regeneration. Biomaterials. 2014;35(18): 4929-4939. [38] YANG B, CHEN G, LI J, et al. Tooth root regeneration using dental follicle cell sheets in combination with a dentin matrix - based scaffold. Biomaterials. 2012;33(8):2449-2461. [39] GUO W, GONG K, SHI H, et al. Dental follicle cells and treated dentin matrix scaffold for tissue engineering the tooth root. Biomaterials. 2012;33(5):1291-1302. [40] 韩雪,郭维华.同种异体牙囊细胞膜片在异种生物牙根再生中作用[J].实用口腔医学杂志,2020,36(2):290-294. [41] JUNG C, KIM S, SUN T, et al. Pulp-dentin regeneration: current approaches and challenges. J Tissue Eng. 2019;10:2041731418819263. [42] BAI Y, BAI Y, MATSUZAKA K, et al. Formation of bone-like tissue by dental follicle cells co-cultured with dental papilla cells. Cell Tissue Res. 2010;342(2):221-231. [43] JUNG HS, LEE DS, LEE JH, et al. Directing the differentiation of human dental follicle cells into cementoblasts and/or osteoblasts by a combination of HERS and pulp cells. J Mol Histol. 2011;42(3):227-235. [44] TAKAHASHI K, OGURA N, TOMOKI R, et al. Applicability of human dental follicle cells to bone regeneration without dexamethasone: an in vivo pilot study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;44(5):664-669. [45] VIALE-BOURONCLE S, BEY B, REICHERT TE, et al. beta-tricalcium-phosphate stimulates the differentiation of dental follicle cells. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2011;22(7):1719-1724. [46] VIALE-BOURONCLE S, BUERGERS R, MORSCZECK C, et al. β-Tricalcium phosphate induces apoptosis on dental follicle cells. Calcif Tissue Int. 2013;92(5):412-417. [47] AO C, NIU Y, ZHANG X, et al. Fabrication and characterization of electrospun cellulose/nano-hydroxyapatite nanofibers for bone tissue engineering. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017;97:568-573. [48] OLTEANU D, FILIP A, SOCACI C, et al. Cytotoxicity assessment of graphene-based nanomaterials on human dental follicle stem cells. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2015;136:791-798. [49] REZAI-RAD M, BOVA JF, OROOJI M, et al. Evaluation of bone regeneration potential of dental follicle stem cells for treatment of craniofacial defects. Cytotherapy. 2015;17(11):1572-1581. [50] LUCACIU O, SORIŢĂU O, GHEBAN D, et al. Dental follicle stem cells in bone regeneration on titanium implants. BMC Biotechnol. 2015;15:114. [51] KINANE DF, STATHOPOULOU PG, PAPAPANOU PN. Periodontal diseases. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17038. [52] 陈发明.牙周组织工程与再生[J].中华口腔医学杂志,2017,52(10): 610-614. [53] GUO Y, GUO W, CHEN J, et al. Are Hertwig’s epithelial root sheath cells necessary for periodontal formation by dental follicle cells? Arch Oral Biol. 2018;94:1-9. [54] GUO W, CHEN L, GONG K, et al. Heterogeneous dental follicle cells and the regeneration of complex periodontal tissues. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012;18(5-6):459-470. [55] GUO S, GUO W, DING Y, et al. Comparative study of human dental follicle cell sheets and periodontal ligament cell sheets for periodontal tissue regeneration. Cell Transplant. 2013;22(6):1061-1073. [56] GUO S, KANG J, JI B, et al. Periodontal-Derived Mesenchymal Cell Sheets Promote Periodontal Regeneration in Inflammatory Microenvironment. Tissue Eng Part A. 2017;23(13-14):585-596. [57] HAN X, LIAO L, ZHU T, et al. Xenogeneic native decellularized matrix carrying PPARγ activator RSG regulating macrophage polarization to promote ligament-to-bone regeneration. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2020;116:111224. [58] NIVEDHITHA SUNDARAM M, SOWMYA S, DEEPTHI S, et al. Bilayered construct for simultaneous regeneration of alveolar bone and periodontal ligament. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2016; 104(4):761-770. [59] SOWMYA S, MONY U, JAYACHANDRAN P, et al. Tri-Layered Nanocomposite Hydrogel Scaffold for the Concurrent Regeneration of Cementum, Periodontal Ligament, and Alveolar Bone. Adv Healthc Mater. 2017;6(7):1601251. [60] LI H, SUN J, LI J, et al. Xenogeneic Bio-Root Prompts the Constructive Process Characterized by Macrophage Phenotype Polarization in Rodents and Nonhuman Primates. Adv Healthc Mater. 2017;6(5):1601112. [61] YANG H, LI J, HU Y, et al. Treated dentin matrix particles combined with dental follicle cell sheet stimulate periodontal regeneration. Dent Mater. 2019;35(9):1238-1253. |

| [1] | Jiang Huanchang, Zhang Zhaofei, Liang De, Jiang Xiaobing, Yang Xiaodong, Liu Zhixiang. Comparison of advantages between unilateral multidirectional curved and straight vertebroplasty in the treatment of thoracolumbar osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(9): 1407-1411. |

| [2] | Xue Yadong, Zhou Xinshe, Pei Lijia, Meng Fanyu, Li Jian, Wang Jinzi . Reconstruction of Paprosky III type acetabular defect by autogenous iliac bone block combined with titanium plate: providing a strong initial fixation for the prosthesis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(9): 1424-1428. |

| [3] | Zhu Chan, Han Xuke, Yao Chengjiao, Zhou Qian, Zhang Qiang, Chen Qiu. Human salivary components and osteoporosis/osteopenia [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(9): 1439-1444. |

| [4] | Jin Tao, Liu Lin, Zhu Xiaoyan, Shi Yucong, Niu Jianxiong, Zhang Tongtong, Wu Shujin, Yang Qingshan. Osteoarthritis and mitochondrial abnormalities [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(9): 1452-1458. |

| [5] | Zhang Lichuang, Xu Hao, Ma Yinghui, Xiong Mengting, Han Haihui, Bao Jiamin, Zhai Weitao, Liang Qianqian. Mechanism and prospects of regulating lymphatic reflux function in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(9): 1459-1466. |

| [6] | Yao Xiaoling, Peng Jiancheng, Xu Yuerong, Yang Zhidong, Zhang Shuncong. Variable-angle zero-notch anterior interbody fusion system in the treatment of cervical spondylotic myelopathy: 30-month follow-up [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(9): 1377-1382. |

| [7] | Li Wei, Zhu Hanmin, Wang Xin, Gao Xue, Cui Jing, Liu Yuxin, Huang Shuming. Effect of Zuogui Wan on bone morphogenetic protein 2 signaling pathway in ovariectomized osteoporosis mice [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(8): 1173-1179. |

| [8] | Wang Jing, Xiong Shan, Cao Jin, Feng Linwei, Wang Xin. Role and mechanism of interleukin-3 in bone metabolism [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(8): 1260-1265. |

| [9] | Xiao Hao, Liu Jing, Zhou Jun. Research progress of pulsed electromagnetic field in the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(8): 1266-1271. |

| [10] | Zhu Chan, Han Xuke, Yao Chengjiao, Zhang Qiang, Liu Jing, Shao Ming. Acupuncture for Parkinson’s disease: an insight into the action mechanism in animal experiments [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(8): 1272-1277. |

| [11] | Wu Bingshuang, Wang Zhi, Tang Yi, Tang Xiaoyu, Li Qi. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: from enthesis to tendon-to-bone healing [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(8): 1293-1298. |

| [12] | Wu Weiyue, Guo Xiaodong, Bao Chongyun. Application of engineered exosomes in bone repair and regeneration [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(7): 1102-1106. |

| [13] | Zhou Hongqin, Wu Dandan, Yang Kun, Liu Qi. Exosomes that deliver specific miRNAs can regulate osteogenesis and promote angiogenesis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(7): 1107-1112. |

| [14] | Zhang Jinglin, Leng Min, Zhu Boheng, Wang Hong. Mechanism and application of stem cell-derived exosomes in promoting diabetic wound healing [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(7): 1113-1118. |

| [15] | Huang Chenwei, Fei Yankang, Zhu Mengmei, Li Penghao, Yu Bing. Important role of glutathione in stemness and regulation of stem cells [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2022, 26(7): 1119-1124. |

| Viewed | ||||||

|

Full text |

|

|||||

|

Abstract |

|

|||||