Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research ›› 2026, Vol. 30 ›› Issue (15): 3971-3982.doi: 10.12307/2026.668

Previous Articles Next Articles

Mechanism and therapeutic potential of nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 in regulating non-infectious spinal diseases

Huang Lei1, Wang Xianghong2, Zhang Xianxu1, Li Shicheng1, Luo Zhiqiang1

- 1Department of Orthopedics, Second Hospital of Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 730000, Gansu Province, China; 2Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology, Jiuquan Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Jiuquan 735000, Gansu Province, China

-

Accepted:2025-06-30Online:2026-05-28Published:2025-11-10 -

Contact:Luo Zhiqiang, PhD, Chief physician, Department of Orthopedics, Second Hospital of Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 730000, Gansu Province, China -

About author:Huang Lei, MS, Department of Orthopedics, Second Hospital of Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 730000, Gansu Province, China Wang Xianghong, Chief physician, Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology, Jiuquan Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Jiuquan 735000, Gansu Province, China Huang Lei and Wang Xianghong contributed equally to this article. -

Supported by:Cuiying Science and Technology Innovation Program of Second Hospital of Lanzhou University, No. CY2021-MS-A03 (to LZQ)

CLC Number:

Cite this article

Huang Lei, Wang Xianghong, Zhang Xianxu, Li Shicheng, Luo Zhiqiang. Mechanism and therapeutic potential of nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 in regulating non-infectious spinal diseases[J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(15): 3971-3982.

share this article

Add to citation manager EndNote|Reference Manager|ProCite|BibTeX|RefWorks

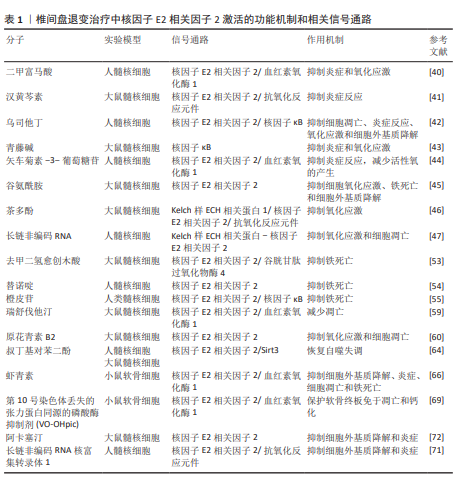

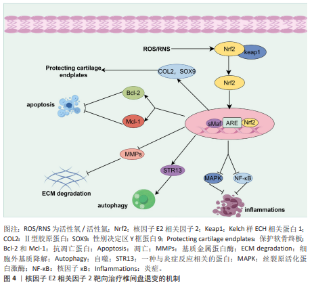

2.1 核因子E2相关因子2简介 2.1.1 核因子E2相关因子2结构 核因子E2相关因子2属于基本亮氨酸拉链因子Cap’n’Collar亚家族,它包含7个高度保守的Neh结构域[13],分别为Neh1-Neh7。Neh1含有CNC型亮氨酸拉链结构,是核因子E2相关因子2与DNA结合并与其他转录因子形成二聚体的必要条件,Neh1区域主要与细胞核内的小Maf蛋白(small Maf proteins)形成异二聚体,使核因子E2相关因子2能够识别并结合抗氧化反应元件,从而启动靶基因的转录。NNeh2结构域包含DLG和ETGE基序,二者均可与Kelch样ECH关联蛋白1结合,从而调控核因子E2相关因子2的泛素化和稳定性,并阻止核因子E2相关因子2启动其抗氧化功能[14]。Neh3结构域位于核因子E2相关因子2的C端,对维持其转录活性至关重要[15]。Neh4和Neh5可与环磷腺苷效应元件结合蛋白结合调控核因子E2相关因子2靶基因。Neh6富含丝氨酸,含DSGIS和DSAPGS基序,被β-转导重复相容蛋白识别,诱导核因子E2相关因子2降解[16-17]。Neh7结构域能够结合核受体维甲类X受体α,从而抑制核因子E2相关因子2-抗氧化反应元件信号通路[18]。 2.1.2 Kelch样ECH相关蛋白1-核因子E2相关因子2-抗氧化反应元件 Kelch样ECH相关蛋白1是一种由KEAP1基因编码的蛋白质,包含3个主要功能域:BTB结构域、干预区域和Kelch结构域[19-20]。在细胞氧化还原水平稳定时,大部分核因子E2相关因子2与Kelch样ECH相关蛋白1结合,并通过泛素-蛋白酶体系统迅速降解,从而维持核因子E2相关因子2的稳定表达并使其处于非活性状态[21-22]。当机体受到氧化应激,如活性氧过度堆积时,核因子E2相关因子2会被激活[23]。活性氧主要通过修饰Kelch样ECH相关蛋白1中的C273、C288或C151半胱氨酸残基的巯基基团,引起Kelch样ECH相关蛋白1构象改变,从而导致其与核因子E2相关因子2解离,使核因子E2相关因子2进入细胞核发挥作用[24]。核因子E2相关因子2通过与人特异性巨噬细胞武装因子蛋白形成异源二聚体来结合抗氧化反应元件[25],这导致含有抗氧化反应元件的细胞保护基因的激活[26]。核因子E2相关因子2能够促进抗氧化酶和细胞保护蛋白的表达,包括谷胱甘肽过氧化物酶、超氧化物歧化酶和过氧化氢酶,这些酶通过清除体内活性氧从而抑制炎症反应[27-28]。它还促进抗炎因子的上调,如血红素氧化酶1和抗氧化酶过氧化物氧化酶1[29-30],这些因子可以选择性地抑制脂多糖诱导的促炎因子肿瘤坏死因子、白细胞介素1和巨噬细胞炎症蛋白1B的表达[31]。核因子E2相关因子2信号通路见图3。"

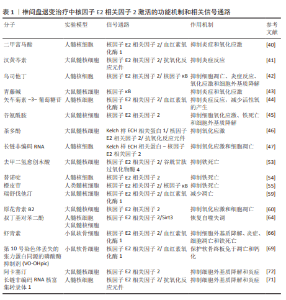

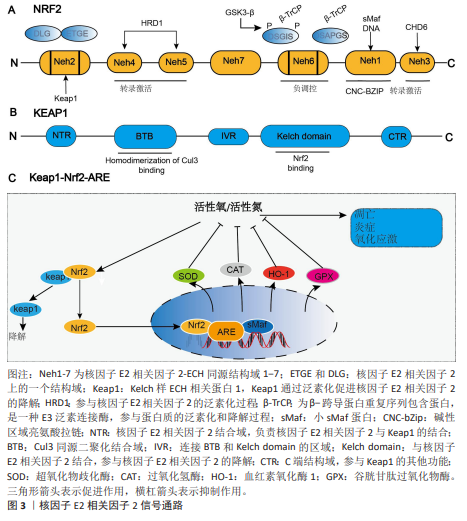

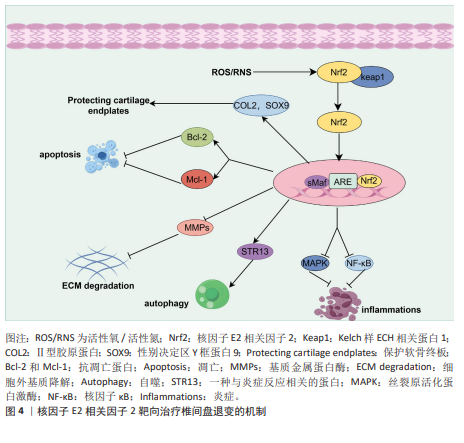

2.2 核因子E2相关因子2在椎间盘退变中的研究进展 2.2.1 椎间盘退变简介 椎间盘是位于脊椎骨之间的结构,主要由髓核、纤维环和软骨终板3部分组成[32]。髓核位于椎间盘的中心,纤维环位于椎间盘的外周,由多层同心圆状排列的纤维软骨环组成,它的主要作用在于保持脊柱稳定,防止椎间盘突出。椎体上下两侧的软骨终板是一层透明软骨,是连接富含血管的椎骨与无血管椎间盘组织之间进行营养物质交换的关键结构[33]。椎间盘退变是最常见的非感染性脊柱疾病之一,也是慢性下背痛的重要致病因素。椎间盘退变指椎间盘结构和功能的逐渐退化,常引发椎管狭窄、脊柱不稳及腰腿痛等病症[34]。椎间盘退变的发生通常伴随着炎症反应、氧化应激、细胞死亡以及细胞外基质的降解等一系列病理变化,这些因素在椎间盘退变的进程中相互作用,最终导致椎间盘功能障碍、结构损伤和临床症状的表现[35],其中炎症反应、氧化应激都是椎间盘退变的重要机制。在椎间盘退变过程中,核因子E2相关因子2作为关键转录因子,通过激活一系列抗氧化酶调控氧化应激反应,减轻活性氧对椎间盘细胞的损伤,进而抑制细胞凋亡和细胞外基质降解,从而延缓椎间盘退变进程。核因子E2相关因子2还可下调肿瘤坏死因子和白细胞介素1β等炎症因子,抑制核因子κB通路,降低基质金属蛋白酶等基质降解酶的表达。目前椎间盘退变的治疗仍以对症手段为主,难以逆转退变。越来越多研究指出,调节核因子E2相关因子2通路具有潜在的再生治疗价值。诸如姜黄素、辛弗林等天然激活剂在实验中表现出延缓退变、改善细胞功能的效果。因此,核因子E2相关因子2有望成为椎间盘退变治疗的新靶点,为临床带来新的干预策略。 2.2.2 核因子E2相关因子2对髓核细胞炎症和氧化应激的作用 过度的炎症反应显著影响髓核细胞的正常功能。多种促炎细胞因子(白细胞介素1β、肿瘤坏死因子、白细胞介素6、白细胞介素8、白细胞介素17和干扰素γ)在退变椎间盘中的表达水平升高,这些因子在椎间盘退变中通过调控椎间盘基质合成与分解、炎症反应及椎间盘细胞凋亡发挥关键作用[36-39]。核因子E2相关因子2是一种关键的抗氧化转录因子,不仅抑制炎症因子的产生,还调控炎症相关信号通路。研究表明,经脂多糖诱导后,髓核细胞中活性氧和炎症因子的表达显著升高。然而,二甲富马酸通过核因子E2相关因子2/血红素氧化酶-1途径抑制脂多糖诱导的内质网应激,从而降低了这些炎症因子的水平[40]。五味子素以剂量和时间依赖性方式激活核因子E2相关因子2的表达,以及核因子E2相关因子2依赖的抗氧化反应元件调控的基因,如超氧化物歧化酶2、血红素氧化酶1。此外,汉黄芩素通过核因子E2相关因子2逆转白细胞介素1β诱导的丝裂原活化蛋白激酶信号通路激活,从而保护了髓核细胞[41]。研究还发现,从人尿中提取的抗炎酸性蛋白(乌司他丁)通过激活核因子E2相关因子2/血红素氧化酶1信号通路并抑制核因子κB信号通路,显著降低人髓核细胞中相关促炎介质的表达水平,从而减轻炎症反应[42]。 氧化应激通过多种机制损伤椎间盘细胞和组织,是椎间盘退变的重要致病因素之一。氧化应激的产生主要由活性氧引起,因此,降低活性氧水平有助于抵御氧化应激反应。莫拉辛通过核因子E2相关因子2/血红素氧化酶1和核因子κB/转化生长因子β通路显著降低了脂多糖诱导的丙二醛活性,同时提高了超氧化物歧化酶和过氧化氢酶的水平。超氧化物歧化酶和过氧化氢酶能够清除有害的自由基和过氧化氢,减少氧化应激,从而保护椎间盘免受退变。LU等[43]发现,青藤碱通过激活Kelch样ECH相关蛋白1/核因子E2相关因子2通路,逆转了白细胞介素1β引起的髓核细胞活性显著下降、活性氧积累及细胞凋亡。此外,研究表明,矢车菊素-3-葡萄糖苷通过核因子E2相关因子2/血红素氧化酶1信号通路显著减少活性氧的产生,从而保护椎间盘细胞免受高浓度葡萄糖诱导的损伤[44]。谷氨酰胺[45]、茶多酚和长链非编码RNA等活性物质通过核因子E2相关因子2抑制炎症反应并减轻氧化应激[46-47],从而延缓椎间盘退变的进展。综上所述,针对核因子E2相关因子2的药物和生物活性物质通过促进下游抗氧化基因(如血红素氧化酶1、超氧化物歧化酶、过氧化氢酶和醌氧化还原酶1)的转录,能够有效对抗髓核细胞中的炎症和氧化应激。 2.2.3 核因子E2相关因子2对髓核细胞死亡(铁死亡、凋亡、自噬)的作用 细胞死亡通过多种机制参与椎间盘退变的过程,而细胞的死亡方式包括铁死亡、凋亡、焦亡和自噬等,其中铁死亡是细胞程序性死亡的一种方式[48-49],其特征为细胞内铁水平升高、谷胱甘肽耗竭和铁死亡抑制基因谷胱甘肽过氧化物酶4的核心失活,导致脂质过氧化和随后的细胞死亡[50-51]。在椎间盘退变的进程中,铁离子在细胞质和线粒体之间持续积累,并与氧发生反应,产生大量氧自由基,最终导致细胞膜、蛋白质及其他细胞结构损伤,甚至诱发细胞死亡[52]。铁死亡与核因子E2相关因子2密切相关,因此这一领域已引起广泛关注。近期ZHANG等[53]发现,去甲二氢愈创木酸通过上调核因子E2相关因子2的表达,进一步促进谷胱甘肽过氧化物酶4的表达,从而保护了髓核细胞。YANG等[54]发现,替诺啶通过核因子E2相关因子2能够逆转髓核细胞铁死亡。橙皮苷是一种来源于柑橘类水果的黄烷酮糖苷,具有较强的抗氧化活性。研究表明,橙皮苷通过增强核因子E2相关因子2的表达并抑制核因子κB通路,抑制铁死亡,从而保护细胞免受氧化损伤[55]。此外,研究发现,白藜芦醇能够增加铁死亡抑制基因(谷胱甘肽过氧化物酶4和核因子E2相关因子2)的表达,抑制细胞内Fe2?的积累及脂质过氧化物和活性氧的生成,从而预防椎间盘退变[56]。 凋亡在椎间盘退变的发生与进展中发挥着重要作用,而它的主要病理基础是髓核细胞数量的减少及其引发的细胞外基质合成减少,而过度凋亡是导致髓核细胞减少的主要原因[57-58]。ZHANG等[59]发现,瑞舒伐他汀通过激活核因子E2相关因子2/血红素氧化酶1信号通路显著减少了机械压力诱导的细胞凋亡。然而,当抑制核因子E2相关因子2信号通路时,磷酸化核因子E2相关因子2、血红素氧化酶1和醌氧化还原酶1的表达水平下降,凋亡显著增加。此外,研究表明,原花青素B2通过激活磷酸肌醇3-激酶/蛋白激酶B信号通路,上调核因子E2相关因子2的表达,从而减轻氧化应激诱导的大鼠髓核细胞凋亡[60]。 自噬是一种高度保守的细胞内分解代谢过程,涉及细胞内物质的回收和再利用,维持代谢稳定,并在应激条件下防止受损或有毒蛋白质及细胞器的积累[61]。自噬受到哺乳动物雷帕霉素靶蛋白信号通路的负调控,哺乳动物雷帕霉素靶蛋白的抑制可促进自噬的激活[62]。自噬的调控依赖于自噬相关基因和蛋白质,这些是其关键调节因子。在生理条件下,Atg蛋白的表达相对较低,基础自噬通过分解废物维持细胞稳态;在应激条件下自噬相关蛋白被激活并诱导自噬[63]。研究表明,叔丁基对苯二酚通过核因子E2相关因子2/Sirt3通路恢复了叔丁过氧化氢诱导的自噬通量紊乱,从而改善了大鼠椎间盘退变的进展[64]。自噬能够促进核因子E2相关因子2的表达及核转位,并激活核因子E2相关因子2/Kelch样ECH相关蛋白1信号通路,从而增强抗氧化基因的表达。一致的研究结果表明,核因子E2相关因子2通过激活Kelch样ECH相关蛋白1-核因子E2相关因子2-p62信号通路促进自噬,从而保护椎间盘免受退变。 2.2.4 核因子E2相关因子2对软骨终板作用 软骨终板是椎间盘的主要营养交换组织,表面的微孔保持开放,维持半渗透膜特性,使营养物质能够透过这些微孔进入软骨终板的浅层,随后渗透至髓核和纤维环的内层,软骨终板的退化会引起营养物质运输障碍和缺氧,进而增强椎间盘内细胞的无氧代谢,导致乳酸堆积和椎间盘pH值下降,加速椎间盘退变的进展[65]。 核因子E2相关因子2能够通过多种途径保护软骨终板。YANG等[66]发现,虾青素通过激活核因子E2相关因子2/血红素氧化酶1通路,增加性别决定区Y框蛋白9的表达,同时下调了Ⅹ型胶原蛋白α1链和Runt相关转录因子2的表达。Ⅱ型胶原和性别决定区Y框蛋白9共同维持软骨终板的健康与功能,而Ⅹ型胶原蛋白α1和RUNT相关转录因子2则对软骨终板的结构和功能产生不利影响[67]。此外,MA等[68]发现,核因子E2相关因子2通过抑制核受体共激活因子4介导的铁蛋白自噬过程,保护软骨终板免受退化。CUI等[69]发现第10号染色体丢失的张力蛋白同源的磷酸酶基因抑制剂(VO-OHpic)通过激活核因子E2相关因子2/血红素氧化酶1途径,减轻了软骨终板钙化和椎间盘退变的进展。 2.2.5 核因子E2相关因子2对髓核细胞中细胞外基质的作用 髓核细胞的主要成分包括细胞外基质、Ⅱ型胶原蛋白和蛋白聚糖。椎间盘退变的典型特征是细胞外基质的降解,其代谢产物的积累会进一步恶化椎间盘的微环境。因此,维持细胞外基质合成与降解之间的平衡,有助于保持椎间盘的生物力学功能和结构稳定性。研究表明,核因子E2相关因子2主要通过调控髓核细胞内的信号通路和基因表达,进而影响细胞行为,最终间接作用于细胞外基质。研究发现,吴茱萸碱能够逆转叔丁过氧化氢诱导的细胞外基质分解代谢标志物,如基质金属蛋白酶3、基质金属蛋白酶13的水平升高,从而对细胞外基质具有保护作用。此外,研究还表明,吴茱萸碱通过抑制核因子E2相关因子2/血红素氧化酶1和c-Jun氨基末端激酶途径相关的线粒体功能障碍、细胞外基质降解和炎症,从而改善了椎间盘退变的进程。WANG等[70]发现,阿卡塞汀通过激活核因子E2相关因子2通路并抑制p38、c-Jun氨基末端激酶和细胞外信号调节激酶1/2的磷酸化,缓解了叔丁过氧化氢诱导的炎症递质生成及细胞外基质的降解。此外,研究发现,长链非编码RNA核富集转录体1的过表达能够促进分解代谢标志物的mRNA表达,同时抑制合成代谢标志物的表达[71]。此外,核因子E2相关因子2激活剂叔丁基对苯二酚部分逆转了长链非编码RNA核富集转录体1对细胞外基质代谢的影响,表明长链非编码RNA核富集转录体1通过调控核因子E2相关因子2信号通路的激活,改善了髓核细胞中细胞外基质降解。综上所述,通过调控核因子E2相关因子2信号通路以减轻髓核细胞的细胞外基质降解,可能成为治疗椎间盘退变的一种潜在策略。根据以上研究结果,研究表明,靶向核因子E2相关因子2信号轴可通过多种途径延缓椎间盘退变,可能是干预和治疗椎间盘退变的一种有效方法(图 4)。 除上述分子机制外,许多其他机制和相关信号通路也阐明了核因子E2相关因子2激活在 椎间盘退变治疗中的作用,如表1所示。"

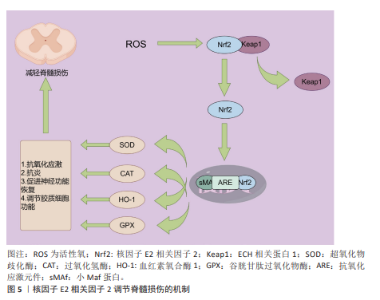

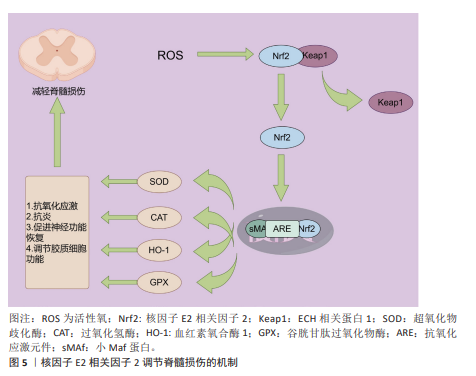

2.3 核因子E2相关因子2在脊髓损伤中的研究进展 2.3.1 脊髓损伤与氧化应激 脊髓损伤是由外界直接或间接因素引起的,通常伴随炎症反应和细胞凋亡等生物学机制,导致受损脊髓节段的感官、运动以及自主神经功能受到不同程度的障碍[72]。脊髓损伤的病理生理机制极为复杂,通常可以分为原发性损伤和继发性损伤两大类[73]。原发性损伤多由直接的机械性损伤引发[74],继发性损伤则是由原发性损伤所引发的一系列生化、机械以及生理变化,包括缺血、氧化应激、炎症反应、神经细胞死亡、脱髓鞘及瘢痕形成等过程[75-76]。氧化应激,作为脊髓损伤继发性损伤的重要机制之一,是指活性氧生成与机体抗氧化防御系统之间的失衡状态[77]。活性氧包括超氧阴离子、过氧化氢、单线态氧和羟基自由基等,它们是在正常氧代谢过程中自然生成的高度活性分子。在脊髓损伤过程中,活性氧通过激活细胞凋亡相关信号通路促使神经细胞发生程序性死亡。此外,活性氧还能破坏线粒体膜电位,导致线粒体功能失调并诱发更多活性氧的产生,形成恶性循环,从而加剧神经损伤。在脊髓损伤后,谷氨酸水平的显著升高导致钙离子内流,进而引发钙超载;钙超载进一步激活线粒体内的烟酰胺腺嘌呤二核苷酸磷酸氧化酶,促使更多活性氧和活性氮的生成,从而加剧氧化应激和线粒体功能损伤[78]。过量的活性氧和活性氮通过与DNA、脂质及蛋白质相互作用,诱发细胞损伤和死亡,进而加重脊髓损伤的严重性[79]。有研究发现,miRNA-7a 的上调能够通过抑制脊髓损伤大鼠中的核因子κB通路,减轻损伤所引发的氧化应激反应,从而改善相关损伤[80]。此外,miRNA-153通过靶向神经分化相关基因,显著减轻了炎症反应和氧化应激,对脊髓损伤具有一定的保护作用[81]。因此,抑制氧化应激被认为是治疗脊髓损伤的一种潜在策略,值得在未来的研究中进一步探讨[82]。 2.3.2 核因子E2相关因子2对脊髓损伤后氧化应激的作用 如前所述,脊髓损伤后,氧化应激是继发性损伤的重要组成部分,能够显著加剧损伤部位微环境的恶化,进而推动神经功能的进一步衰退。核因子E2相关因子2作为氧化应激反应中的关键转录因子,广泛参与体内抗氧化防御的调节,进而在脊髓损伤的病理过程中扮演着保护性角色。正常情况下,核因子E2相关因子2通过调节细胞内的抗氧化酶系统、蛋白质降解、DNA修复及线粒体膜的完整性维护来维持细胞的稳定[73,82]。在病理情况下,核因子E2相关因子2的激活能够有效抵抗氧化应激相关疾病的发生,如阿尔茨海默病、帕金森病、癫痫、衰老及缺血等,这些疾病均与持续的氧化应激密切相关[74]。在脊髓损伤发生后,氧化应激的加剧不仅促进了细胞内钙超载、白细胞活化、线粒体功能损伤及神经元凋亡的发生,还加重了局部的炎症反应[83-84]。核因子E2相关因子2途径的激活被证明能够通过一系列生物学机制缓解这些继发性损伤,尤其是在神经元和胶质细胞中,发挥关键的保护作用。具体来说,氧化应激诱导下,核因子E2相关因子2从其抑制因子Kelch样ECH相关蛋白1中解离,转入细胞核。在核内,核因子E2相关因子2与sMaf蛋白结合,形成异源二聚体,进而通过结合抗氧化反应元件上的增强子序列,启动一系列抗氧化酶基因的转录,这些基因包括血红素氧化酶1、超氧化物歧化酶、醌氧化还原酶1等,它们通过清除过量的活性氧来减轻氧化损伤[85-86]。这些酶通过在细胞内建立强大的抗氧化防御系统,不仅减少了活性氧的产生,还在根本上保护了细胞免受氧化损伤的侵害。特别是血红素氧化酶1,它作为一种内源性抗氧化酶,在脊髓损伤后损伤区域持续表达,并起到限制氧化应激、减缓神经元死亡的作用[87]。血红素氧化酶1不仅能清除活性氧,还能够通过分解血红素生成一氧化碳等信号分子,进一步调节免疫反应,减少炎症递质的释放[88]。此外,核因子E2相关因子2的激活还能够上调其他抗氧化酶的表达,如超氧化物歧化酶和谷胱甘肽过氧化物酶,这些酶能够有效清除线粒体内产生的过量活性氧,从而保护线粒体功能免受进一步损害。越来越多的研究表明,核因子E2相关因子2的活化对脊髓损伤后的恢复具有重要意义。通过外源性激活核因子E2相关因子2途径,一些药物已被证明能够显著减轻损伤。例如,阿卡塞汀通过激活核因子E2相关因子2/血红素氧化酶1信号通路,降低了脊髓损伤诱导的炎症因子的高浓度,并有效抑制了氧化应激反应,展现出明显的保护作用[87]。ZHAO等[89]研究发现,星形胶质细胞中核因子E2相关因子2的激活能够显著缓解小鼠脊髓中的氧化应激和炎症反应,进一步验证了核因子E2相关因子2在其中的保护作用。柑橘黄酮也被证明通过激活Sestrin2/Kelch样ECH相关蛋白1/核因子E2相关因子2通路,改善小鼠的运动功能恢复,减少神经元损失和损伤面积;该化合物不仅通过抑制活性氧的产生减少了氧化损伤,还降低了炎症反应,表现出强大的多重保护作用[90]。此外,LUO等[91]研究发现,通过补髓活血方治疗脊髓损伤小鼠后,超氧化物歧化酶水平显著逆转,同时,核因子E2相关因子2、醌氧化还原酶1和血红素氧化酶1等抗氧化酶的表达也显著上调。这些变化进一步证实了其在激活抗氧化反应、减少脊髓损伤应激以及抑制细胞凋亡方面的潜力。通过这些研究结果可以看出,核因子E2相关因子2不仅在脊髓损伤后的氧化应激中发挥关键作用,还可能通过调节多种抗氧化酶和信号通路来减少继发性损伤,从而为脊髓损伤的治疗提供了新的潜在靶点。随着核因子E2相关因子2相关药物和治疗策略的进一步研究,未来可能为脊髓损伤患者提供更多的治疗选择。核因子E2相关因子2调节脊髓损伤的作用机制见图5。"

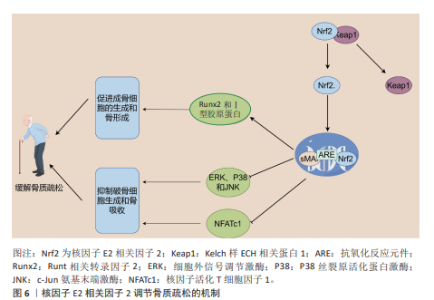

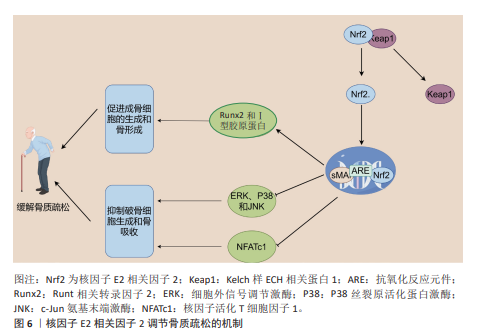

2.4 核因子E2相关因子2在骨质疏松中的研究进展 骨质疏松是一种以全身骨密度降低、骨量减少、骨组织微结构恶化以及骨脆性增强为特征的常见慢性骨骼疾病[92]。骨质疏松的发生机制相当复杂,主要表现为骨重建过程中的失衡,特别是破骨细胞与成骨细胞之间的动态平衡被打破,当破骨细胞的活性过度增强或成骨细胞功能减弱时,骨质流失加剧,从而加速骨质疏松的进展。近年来,核因子E2相关因子2被认为在调节骨代谢和维持骨骼健康方面发挥着至关重要的作用,尤其是在平衡成骨细胞和破骨细胞功能方面[93]。一方面,激活核因子E2相关因子2/抗氧化反应元件信号通路能够通过调控细胞内活性氧水平,抑制丝裂原活化蛋白激酶和磷酸肌醇3-激酶/蛋白激酶B信号通路的激活。丝裂原活化蛋白激酶信号通路在破骨细胞形成和骨吸收过程中扮演着重要角色。研究表明,核因子E2相关因子2通过抑制丝裂原活化蛋白激酶通路的激活,能够减少破骨细胞的分化和活性,从而减缓骨质疏松的进展[94]。细胞致瘤基因蛋白(原癌基因c-Myc)作为一种重要的转录因子,能够调控活化T细胞核因子,进而促进破骨细胞的生成[95]。核因子活化T细胞因子1在破骨细胞的终末分化过程中发挥着核心作用,它激活多种破骨基因的表达,如抗酒石酸酸性磷酸酶和组织蛋白酶K。核因子E2相关因子2通过抑制丝裂原活化蛋白激酶的激活,降低细胞致瘤基因的水平,从而抑制活化T细胞核因子的激活,最终抑制破骨细胞的分化和骨吸收成[95]。此外,研究发现Apelin-13通过激活核因子E2相关因子2通路,抑制核苷酸结合寡聚化结构域样受体蛋白 3介导的细胞焦亡,进一步减轻破骨细胞的活化[96]。核因子E2相关因子2缺陷型破骨细胞前体在核因子κB受体活化因子配体诱导下表现出增强的分化、肌动蛋白环形成及骨吸收,而预先使用核因子E2相关因子2激活剂如姜黄素,能够部分逆转这一现象[97]。核因子κB受体活化因子配体通过与破骨细胞前体表面的核因子κB受体活化因子受体结合,促进破骨细胞的分化与活化。核因子E2相关因子2的缺失显著增强了核因子κB的转录活性,从而加剧了核因子κB受体活化因子配体诱导的破骨细胞生成[98]。这些研究表明,核因子E2相关因子2在破骨细胞生成的调控中发挥着直接或间接的关键作用。 另一方面,核因子E2相关因子2在成骨细胞中的作用较为复杂,呈现出双向调控的特点。一些研究表明,在2型糖尿病培养基条件下,成骨相关蛋白的表达显著下降,而在2型糖尿病和MaR1联合培养基的条件下,成骨功能得以恢复。然而,当通过siRNA敲低核因子E2相关因子2时,MaR1的积极作用被减弱,提示MaR1通过激活核因子E2相关因子2信号通路,改善高糖环境下成骨细胞的功能[99]。XU等[100]发现,维生素D受体的激活能够通过刺激核因子E2相关因子2/谷胱甘肽过氧化物酶4信号通路减轻成骨细胞的铁死亡,这为骨代谢中的抗铁死亡机制提供了新思路。此外,LI等[101]的研究表明,激活核因子E2相关因子2/抗氧化反应元件信号通路可以促进抗铁死亡效应,从而支持成骨细胞的生长和矿化,并提高膜内骨移植的效果。核因子E2相关因子2的激活也促进了原代骨细胞和成骨骨细胞中骨细胞特异性基因的表达,而核因子E2相关因子2敲除则导致Runt相关转录因子2和Ⅰ型胶原蛋白的表达显著下降[102]。尽管核因子E2相关因子2在成骨细胞中通常展现出促进作用,但也有研究指出核因子E2相关因子2的过度激活可能抑制成骨细胞的分化。在核因子E2相关因子2敲除的成骨细胞中,与骨形成相关基因的表达显著上调,表明核因子E2相关因子2的过度激活可能对成骨细胞的正常功能产生负面影响[103]。综上所述,核因子E2相关因子2在骨质疏松的发生发展中发挥着重要的双向调控作用:在破骨细胞中,核因子E2相关因子2的激活抑制破骨细胞的分化和骨吸收;而在成骨细胞中,核因子E2相关因子2的活性则通过促进骨细胞特异性基因的表达,调节成骨功能。然而,核因子E2相关因子2的过度激活可能导致成骨细胞的异常,因此,如何精确调控核因子E2相关因子2的活性成为未来骨质疏松治疗的重要研究方向。核因子E2相关因子2调节骨质疏松的作用机制见图6。 2.5 核因子E2相关因子2在强直性脊柱炎中的研究进展 强直性脊柱炎是一种主要累及脊柱及骶髂关节的慢性、进行性、自身免疫介导的炎性疾病,属于脊柱关节病谱系的重要组成部分[104]。临床上,强直性脊柱炎以慢性腰背痛、脊柱僵硬、晨僵及活动受限为主要表现,随着病情进展,椎体边缘发生骨赘形成、纤维化及钙化,最终导致脊柱关节融合,形成典型的“竹节样脊柱”影像学表现。尽管强直性脊柱炎的确切发病机制尚未完全阐明,现有研究多集中于遗传易感性、免疫异常、慢性感染、炎症因子失调及内分泌因素等方面[105]。近年来,越来越多的证据表明,氧化应激在强直性脊柱炎的发病和进展中发挥了重要作用。研究发现,强直性脊柱炎患者体内活性氧水平升高,氧化应激生物标志物(如丙二醛、8-异前列腺素F2α)显著增加,尤其在疾病活动期更为明显,这提示氧化损伤可能是驱动炎症反应和组织破坏的关键因素之一[106]。 在调控氧化应激的信号网络中,核因子E2相关因子2被认为是关键的转录因子,能够通过激活细胞内多种抗氧化防御机制,减缓氧化应激引发的炎性损伤。核因子E2相关因子2与小Maf蛋白形成异源二聚体,结合至抗氧化反应元件区域,从而启动多种下游抗氧化和解毒相关基因的表达,如血红素氧化酶1、超氧化物歧化酶、醌氧化还原酶1等[26,29]。这些酶类共同作用,清除过量活性氧,减轻组织氧化损伤并抑制炎症通路的持续活化。其中,血红素氧化酶1作为核因子E2相关因子2的经典下游靶基因,在强直性脊柱炎中的作用尤为关键。血红素氧化酶1不仅具有强效的抗氧化活性,还可通过调节炎症因子释放、维持线粒体稳态及调控细胞信号转导,对缓解强直性脊柱炎相关炎症反应具有重要意义[107]。例如,研究表明,转录因子叉头框蛋白O3a通过上调血红素氧化酶1的表达,可有效抑制炎症反应,减轻强直性脊柱炎相关组织损伤与氧化应激[107]。此外,沈瑞明等[108]的研究指出,强直性脊柱炎患者血尿酸水平升高可能通过抑制Kelch样ECH相关蛋白1-核因子E2相关因子2通路活化,削弱机体的抗氧化能力,从而促进炎症因子的表达,进一步加剧疾病活动。最新研究还显示,在强直性脊柱炎患者的椎间关节骨髓组织中,促炎因子白细胞介素1β的表达显著升高,而血红素氧化酶1表达则明显降低,提示核因子E2相关因子2-血红素氧化酶1轴可能在局部组织氧化炎症调控中处于抑制状态。此外,来源于强直性脊柱炎患者的骨髓间充质干细胞中活性氧水平升高,进一步验证了其氧化应激状态增强,这可能对间充质干细胞功能及骨修复能力产生负面影响。在治疗层面,一些天然产物也显示出通过核因子E2相关因子2通路发挥抗氧化及抗炎作用的潜力。例如,蒿属素被证实可上调核因子E2相关因子2及血红素氧化酶1表达,增强细胞抗氧化能力,进而减轻强直性脊柱炎相关的炎症及组织损伤[109]。这为靶向核因子E2相关因子2通路的药物研发提供了理论基础与实践启示。综上所述,核因子E2相关因子2通过调控抗氧化基因表达,抑制氧化应激和炎性反应,在强直性脊柱炎的发病机制中发挥着重要保护作用。未来,围绕核因子E2相关因子2信号通路的靶向治疗策略有望为强直性脊柱炎患者提供新的疾病控制和缓解途径,特别是在疾病早期干预和延缓进展方面具有重要意义。"

| [1] WIDMER J, CORNAZ F, SCHEIBLER G, et al. Biomechanical contribution of spinal structures to stability of the lumbar spine-novel biomechanical insights. Spine J. 2020; 20(10):1705-1716. [2] CORNAZ F, WIDMER J, FARSHAD-AMACKER NA, et al. Biomechanical Contributions of Spinal Structures with Different Degrees of Disc Degeneration. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2021;46(16):E869-E877. [3] WONG CK, MAK RY, KWOK TS, et al. Prevalence, Incidence, and Factors Associated With Non-Specific Chronic Low Back Pain in Community-Dwelling Older Adults Aged 60 Years and Older: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Pain. 2022;23(4):509-534. [4] MA Z, LIU X, ZHANG X, et al. Research progress on long non‑coding RNAs in non‑infectious spinal diseases (Review). Mol Med Rep. 2024;30(3):164. [5] LU Y, SHANG Z, ZHANG W, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of spinal cord injury from 1990 to 2021 and projections for 2050: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease 2021 study. Ageing Res Rev. 2025;103:102598. [6] SMITH E, HOY DG, CROSS M, et al. The global burden of other musculoskeletal disorders: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(8):1462-1469. [7] DING W, HU S, WANG P, et al. Spinal Cord Injury: The Global Incidence, Prevalence, and Disability From the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2022;47(21):1532-1540. [8] OHNISHI T, SUDO H, TSUJIMOTO T, et al. Age-related spontaneous lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration in a mouse model. J Orthop Res. 2018;36(1):224-232. [9] TANG Z, HU B, ZANG F, et al. Nrf2 drives oxidative stress-induced autophagy in nucleus pulposus cells via a Keap1/Nrf2/p62 feedback loop to protect intervertebral disc from degeneration. Cell Death Dis. 2019; 10(7): 510. [10] MOTOHASHI H, YAMAMOTO M. Nrf2-Keap1 defines a physiologically important stress response mechanism. Trends Mol Med. 2004;10(11):549-557. [11] KOBAYASHI A, OHTA T, YAMAMOTO M. Unique Function of the Nrf2-Keap1 Pathway in the Inducible Expression of Antioxidant and Detoxifying Enzymes//Methods in Enzymology. Academic Press, 2004: 273-286. [12] ANANDHAN A, DODSON M, SHAKYA A, et al. NRF2 controls iron homeostasis and ferroptosis through HERC2 and VAMP8. Sci Adv. 2023;9(5):eade9585. [13] TOTOKI Y, TATSUNO K, COVINGTON KR, et al. Trans-ancestry mutational landscape of hepatocellular carcinoma genomes. Nat Genet. 2014;46(12):1267-1273. [14] TONG KI, KATOH Y, KUSUNOKI H, et al. Keap1 Recruits Neh2 through Binding to ETGE and DLG Motifs: Characterization of the Two-Site Molecular Recognition Model. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(8):2887-2900. [15] NIOI P, NGUYEN T, SHERRATT PJ, et al. The Carboxy-Terminal Neh3 Domain of Nrf2 Is Required for Transcriptional Activation. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(24):10895-1906. [16] RADA P, ROJO AI, CHOWDHRY S, et al. SCF/β-TrCP Promotes Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3-Dependent Degradation of the Nrf2 Transcription Factor in a Keap1-Independent Manner. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31(6):1121-1133. [17] MCMAHON M, THOMAS N, ITOH K, et al. Redox-regulated turnover of Nrf2 is determined by at least two separate protein domains, the redox-sensitive Neh2 degron and the redox-insensitive Neh6 degron. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(30):31556-31567. [18] WANG H, LIU K, GENG M, et al. RXRα inhibits the NRF2-ARE signaling pathway through a direct interaction with the Neh7 domain of NRF2. Cancer Res. 2013;73(10): 3097-3108. [19] CANNING P, SORRELL FJ, BULLOCK AN. Structural basis of Keap1 interactions with Nrf2. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;88(Pt B): 101-107. [20] SUZUKI T, TAKAHASHI J, YAMAMOTO M. Molecular Basis of the KEAP1-NRF2 Signaling Pathway. Mol Cells. 2023;46(3): 133-141. [21] ZHANG DD, LO SC, CROSS JV, et al. Keap1 is a redox-regulated substrate adaptor protein for a Cul3-dependent ubiquitin ligase complex. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(24): 10941-10953. [22] CULLINAN SB, GORDAN JD, JIN J, et al. The Keap1-BTB Protein Is an Adaptor That Bridges Nrf2 to a Cul3-Based E3 Ligase: Oxidative Stress Sensing by a Cul3-Keap1 Ligase. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(19):8477. [23] MORGENSTERN C, LASTRES-BECKER I, DEMIRDÖĞEN BC, et al. Biomarkers of NRF2 signalling: Current status and future challenges. Redox Biol. 2024;72:103134. [24] BAE T, HALLIS SP, KWAK MK. Hypoxia, oxidative stress, and the interplay of HIFs and NRF2 signaling in cancer. Exp Mol Med. 2024;56(3):501-514. [25] OTSUKI A, YAMAMOTO M. Cis-element architecture of Nrf2-sMaf heterodimer binding sites and its relation to diseases. Arch Pharm Res. 2020;43(3):275-285. [26] KIM MJ, JEON JH. Recent Advances in Understanding Nrf2 Agonism and Its Potential Clinical Application to Metabolic and Inflammatory Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(5):2846. [27] NGO V, DUENNWALD ML. Nrf2 and Oxidative Stress: A General Overview of Mechanisms and Implications in Human Disease. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022;11(12): 2345. [28] TEBAY LE, ROBERTSON H, DURANT ST, et al. Mechanisms of activation of the transcription factor Nrf2 by redox stressors, nutrient cues, and energy status and the pathways through which it attenuates degenerative disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;88(Pt B):108-146. [29] CHUANG HC, CHANG CW, CHANG GD, et al. Histone deacetylase 3 binds to and regulates the GCMa transcription factor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(5):1459-1469. [30] HUNG HL, KIM AY, HONG W, et al. Stimulation of NF-E2 DNA binding by CREB-binding protein (CBP)-mediated acetylation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(14):10715-10721. [31] PARK C, CHA HJ, LEE H, et al. The regulation of the TLR4/NF-κB and Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathways is involved in the inhibition of lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation and oxidative reactions by morroniside in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2021;706:108926. [32] ZHANG L, HU S, XIU C, et al. Intervertebral disc-intrinsic Hedgehog signaling maintains disc cell phenotypes and prevents disc degeneration through both cell autonomous and non-autonomous mechanisms. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2024;81(1):74. [33] CRUMP KB, ALMINNAWI A, BERMUDEZ-LEKERIKA P, et al. Cartilaginous endplates: A comprehensive review on a neglected structure in intervertebral disc research. JOR Spine. 2023;6(4):e1294. [34] MENGIS T, BERNHARD L, NÜESCH A, et al. The Expression of Toll-like Receptors in Cartilage Endplate Cells: A Role of Toll-like Receptor 2 in Pro-Inflammatory and Pro-Catabolic Gene Expression. Cells. 2024; 13(17):1402. [35] TERAGUCHI M, YOSHIMURA N, HASHIZUME H, et al. Prevalence and distribution of intervertebral disc degeneration over the entire spine in a population-based cohort: the Wakayama Spine Study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014;22(1):104-110. [36] JIA J, NIE L, LIU Y. Butyrate alleviates inflammatory response and NF-κB activation in human degenerated intervertebral disc tissues. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;78: 106004. [37] XU H, DAI ZH, HE GL, et al. Gamma-oryzanol alleviates intervertebral disc degeneration development by intercepting the IL-1β/NLRP3 inflammasome positive cycle. Phytomedicine. 2022;102:154176. [38] YU H, LIU Y, XIE W, et al. IL-38 alleviates the inflammatory response and the degeneration of nucleus pulposus cells via inhibition of the NF-κB signaling pathway in vitro. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;85: 106592. [39] CHEN F, JIANG G, LIU H, et al. Melatonin alleviates intervertebral disc degeneration by disrupting the IL-1β/NF-κB-NLRP3 inflammasome positive feedback loop. Bone Res. 2020;8:10. [40] WANG R, LUO D, LI Z, et al. Dimethyl Fumarate Ameliorates Nucleus Pulposus Cell Dysfunction through Activating the Nrf2/HO-1 Pathway in Intervertebral Disc Degeneration. Comput Math Methods Med. 2021;2021:6021763. [41] FANG W, ZHOU X, WANG J, et al. Wogonin mitigates intervertebral disc degeneration through the Nrf2/ARE and MAPK signaling pathways. Int Immunopharmacol. 2018;65: 539-549. [42] LUO X, HUAN L, LIN F, et al. Ulinastatin Ameliorates IL-1β-Induced Cell Dysfunction in Human Nucleus Pulposus Cells via Nrf2/NF-κB Pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021; 2021:5558687. [43] LU G, ZHANG C, LI K, et al. Sinomenine Ameliorates IL-1β-Induced Intervertebral Disc Degeneration in Rats Through Suppressing Inflammation and Oxidative Stress via Keap1/Nrf2/NF-κB Signaling Pathways. J Inflamm Res. 2023;16: 4777-4791. [44] BAI X, LIAN Y, HU C, et al. Cyanidin-3-glucoside protects against high glucose-induced injury in human nucleus pulposus cells by regulating the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling. J Appl Toxicol. 2022;42(7):1137-1145. [45] WU J, HAN W, ZHANG Y, et al. Glutamine Mitigates Oxidative Stress-Induced Matrix Degradation, Ferroptosis, and Pyroptosis in Nucleus Pulposus Cells via Deubiquitinating and Stabilizing Nrf2. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2024;41(4-6):278-295. [46] SONG D, GE J, WANG Y, et al. Tea Polyphenol Attenuates Oxidative Stress-Induced Degeneration of Intervertebral Discs by Regulating the Keap1/Nrf2/ARE Pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021;2021:6684147. [47] KANG L, TIAN Y, GUO X, et al. Long Noncoding RNA ANPODRT Overexpression Protects Nucleus Pulposus Cells from Oxidative Stress and Apoptosis by Activating Keap1-Nrf2 Signaling. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021;2021:6645005. [48] SKOUPILOVÁ H, MICHALOVÁ E, HRSTKA R. Ferroptosis as a New Type of Cell Death and its Role in Cancer Treatment. Klin Onkol. 2018;31(Suppl 2):21-26. [49] MOU Y, WANG J, WU J, et al. Ferroptosis, a new form of cell death: opportunities and challenges in cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2019; 12(1):34. [50] SEIBT T M, PRONETH B, CONRAD M. Role of GPX4 in ferroptosis and its pharmacological implication. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019;133: 144-152. [51] HIRSCHHORN T, STOCKWELL BR. The development of the concept of ferroptosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019; 133: 130-143. [52] LIU J, KANG R, TANG D. Signaling pathways and defense mechanisms of ferroptosis. FEBS J. 2022;289(22):7038-7050. [53] ZHANG Y, LI H, CHEN Y, et al. Nordihydroguaiaretic acid suppresses ferroptosis and mitigates intervertebral disc degeneration through the NRF2/GPX4 axis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024;143(Pt 3): 113590. [54] YANG S, ZHU Y, SHI Y, et al. Screening of NSAIDs library identifies Tinoridine as a novel ferroptosis inhibitor for potential intervertebral disc degeneration therapy. Free Radic Biol Med. 2024;221:245-256. [55] ZHU J, SUN R, YAN C, et al. Hesperidin mitigates oxidative stress-induced ferroptosis in nucleus pulposus cells via Nrf2/NF-κB axis to protect intervertebral disc from degeneration. Cell Cycle. 2023; 22(10):1196-1214. [56] ZHANG P, RONG K, GUO J, et al. Cynarin alleviates intervertebral disc degeneration via protecting nucleus pulposus cells from ferroptosis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023; 165:115252. [57] ZOU M, CHEN W, LI J, et al. Apoptosis Signal-Regulated Kinase-1 Promotes Nucleus Pulposus Cell Senescence and Apoptosis to Regulate Intervertebral Disc Degeneration. Am J Pathol. 2024;194(9):1737-1751. [58] DING F, SHAO Z, XIONG L. Cell death in intervertebral disc degeneration. Apoptosis. 2013;18(7):777-785. [59] ZHANG C, WANG Q, LI K, et al. Rosuvastatin: A Potential Therapeutic Agent for Inhibition of Mechanical Pressure-Induced Intervertebral Disc Degeneration. J Inflamm Res. 2024;17:3825-3838. [60] ZOU YP, ZHANG QC, ZHANG QY, et al. Procyanidin B2 alleviates oxidative stress-induced nucleus pulposus cells apoptosis through upregulating Nrf2 via PI3K-Akt pathway. J Orthop Res. 2023;41(7): 1555-1564. [61] YURUBE T, ITO M, KAKIUCHI Y, et al. Autophagy and mTOR signaling during intervertebral disc aging and degeneration. JOR Spine. 2020;3(1):e1082. [62] TSUJIMOTO R, YURUBE T, TAKEOKA Y, et al. Involvement of autophagy in the maintenance of rat intervertebral disc homeostasis: an in-vitro and in-vivo RNA interference study of Atg5. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2022;30(3):481-493. [63] CHEN HW, ZHOU JW, ZHANG GZ, et al. Emerging role and therapeutic implication of mTOR signalling in intervertebral disc degeneration. Cell Prolif. 2023;56(1): e13338. [64] HU S, ZHANG C, QIAN T, et al. Promoting Nrf2/Sirt3-Dependent Mitophagy Suppresses Apoptosis in Nucleus Pulposus Cells and Protects against Intervertebral Disc Degeneration. Oxid Med Cell Longev, 2021;2021:6694964. [65] CRUMP KB, ALMINNAWI A, BERMUDEZ-LEKERIKA P, et al. Cartilaginous endplates: A comprehensive review on a neglected structure in intervertebral disc research. JOR Spine. 2023;6(4):e1294. [66] YANG G, LIU X, JING X, et al. Astaxanthin suppresses oxidative stress and calcification in vertebral cartilage endplate via activating Nrf-2/HO-1 signaling pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. 2023;119:110159. [67] BUCHWEITZ N, SUN Y, CISEWSKI PORTO S, et al. Regional structure-function relationships of lumbar cartilage endplates. J Biomech. 2024;169:112131. [68] MA Z, LU H, FENG X, et al. Nrf2 protects against cartilage endplate degeneration through inhibiting NCOA4‑mediated ferritinophagy. Int J Mol Med. 2024;53(2): 15. [69] CUI X, LIU X, KONG P, et al. PTEN inhibitor VO-OHpic protects endplate chondrocytes against apoptosis and calcification via activating Nrf-2 signaling pathway. Aging (Albany NY). 2023; 15(6): 2275-2292. [70] WANG H, JIANG Z, PANG Z, et al. Acacetin Alleviates Inflammation and Matrix Degradation in Nucleus Pulposus Cells and Ameliorates Intervertebral Disc Degeneration in vivo. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2020;14:4801-4813. [71] LI C, MA X, NI C, et al. LncRNA NEAT1 promotes nucleus pulposus cell matrix degradation through regulating Nrf2/ARE axis. Eur J Med Res. 2021;26(1):11. [72] WANG H, JIANG Z, PANG Z, et al. Acacetin Alleviates Inflammation and Matrix Degradation in Nucleus Pulposus Cells and Ameliorates Intervertebral Disc Degeneration in vivo. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2020;14:4801-4813. [73] HU X, XU W, REN Y, et al. Spinal cord injury: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic interventions. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):245. [74] ANJUM A, YAZID MD, FAUZI DAUD M, et al. Spinal Cord Injury: Pathophysiology, Multimolecular Interactions, and Underlying Recovery Mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci. 2020; 21(20):7533. [75] ZHU J, LIU Z, LIU Q, et al. Enhanced neural recovery and reduction of secondary damage in spinal cord injury through modulation of oxidative stress and neural response. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):19042. [76] QI Z, PAN S, YANG X, et al. Injectable Hydrogel Loaded with CDs and FTY720 Combined with Neural Stem Cells for the Treatment of Spinal Cord Injury. Int J Nanomedicine. 2024;19:4081-4101. [77] FAKHRI S, ABBASZADEH F, MORADI SZ, et al. Effects of Polyphenols on Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Interconnected Pathways during Spinal Cord Injury. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022;2022:8100195. [78] TORREGROSSA F, SALLÌ M, GRASSO G. Emerging Therapeutic Strategies for Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury. World Neurosurg. 2020;140:591-601. [79] QUADRI SA, FAROOQUI M, IKRAM A, et al. Recent update on basic mechanisms of spinal cord injury. Neurosurg Rev. 2020; 43(2):425-441. [80] DING LZ, XU J, YUAN C, et al. MiR-7a ameliorates spinal cord injury by inhibiting neuronal apoptosis and oxidative stress. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24(1):11-17. [81] QIU T, YIN H, WANG Y, et al. miR-153 attenuates the inflammatory response and oxidative stress induced by spinal cord injury by targeting of NEUROD2. Am J Transl Res. 2021;13(7):7968-7975. [82] COFANO F, BOIDO M, MONTICELLI M, et al. Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Spinal Cord Injury: Current Options, Limitations, and Future of Cell Therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2019; 20(11):2698. [83] LV B, XING S, WANG Z, et al. NRF2 inhibitors: Recent progress, future design and therapeutic potential. Eur J Med Chem. 2024;279:116822. [84] BHAT AA, MOGLAD E, GOYAL A, et al. Nrf2 pathways in neuroprotection: Alleviating mitochondrial dysfunction and cognitive impairment in aging. Life Sci. 2024;357: 123056. [85] INCE S, DEMIREL HH, DEMIRKAPI EN, et al. Magnolin alleviates cyclophosphamide-induced oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis via Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway. Toxicol Res (Camb). 2024;13(4):tfae129. [86] AL-AMARAT W, ABUKHALIL MH, ALRUHAIMI RS, et al. Upregulation of Nrf2/HO-1 Signaling and Attenuation of Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Cell Death Mediate the Protective Effect of Apigenin against Cyclophosphamide Hepatotoxicity. Metabolites. 2022;12(7):648. [87] ZHANG X, XU L, CHEN X, et al. Acacetin alleviates neuroinflammation and oxidative stress injury via the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway in a mouse model of spinal cord injury. Transl Neurosci. 2022;13(1):483-494. [88] CHEN GH, SONG CC, PANTOPOULOS K, et al. Mitochondrial oxidative stress mediated Fe-induced ferroptosis via the NRF2-ARE pathway. Free Rad Biol Med. 2022;180:95-107. [89] ZHAO W, GASTERICH N, CLARNER T, et al. Astrocytic Nrf2 expression protects spinal cord from oxidative stress following spinal cord injury in a male mouse model. J Neuroinflammation. 2022;19(1):134. [90] PENG B, HU J, SUN Y, et al. Tangeretin alleviates inflammation and oxidative response induced by spinal cord injury by activating the Sesn2/Keap1/Nrf2 pathway. Phytother Res. 2024;38(9):4555-4569. [91] LUO D, HOU Y, ZHAN J, et al. Bu Shen Huo Xue Formula Provides Neuroprotection Against Spinal Cord Injury by Inhibiting Oxidative Stress by Activating the Nrf2 Signaling Pathway. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2024;18:4779-4797. [92] ZUR Y, KATCHKOVSKY S, ITZHAR A, et al. Preventing osteoporotic bone loss in mice by promoting balanced bone remodeling through M-CSFRGD, a dual antagonist to c-FMS and αvβ3 receptors. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;282(Pt 2):136821. [93] ASAGIRI M, TAKAYANAGI H. The molecular understanding of osteoclast differentiation. Bone. 2007;40(2):251-264. [94] LI L, DONG H, SONG E, et al. Nrf2/ARE pathway activation, HO-1 and NQO1 induction by polychlorinated biphenyl quinone is associated with reactive oxygen species and PI3K/AKT signaling. Chem Biol Interact. 2014;209:56-67. [95] BAE S, LEE MJ, MUN SH, et al. MYC-dependent oxidative metabolism regulates osteoclastogenesis via nuclear receptor ERRα. J Clin Invest. 2017;127(7):2555-2568. [96] YIN Z, CHENG Q, WANG C, et al. Apelin-13 alleviates osteoclast formation and osteolysis through Nrf2-pyroptosis pathway. Microsc Res Tech. 2024;87(6):1348-1358. [97] HYEON S, LEE H, YANG Y, et al. Nrf2 deficiency induces oxidative stress and promotes RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013; 65:789-799. [98] PARK CK, LEE Y, KIM KH, et al. Nrf2 is a novel regulator of bone acquisition. Bone. 2014;63:36-46. [99] ZHANG Z, JI C, WANG YN, et al. Maresin1 Suppresses High-Glucose-Induced Ferroptosis in Osteoblasts via NRF2 Activation in Type 2 Diabetic Osteoporosis. Cells. 2022;11(16):2560. [100] XU P, LIN B, DENG X, et al. VDR activation attenuates osteoblastic ferroptosis and senescence by stimulating the Nrf2/GPX4 pathway in age-related osteoporosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2022;193(Pt 2):720-735. [101] LI S, LI S, YANG D, et al. NRF2-mediated osteoblast anti-ferroptosis effect promotes induced membrane osteogenesis. Bone. 2024;192:117384. [102] SÁNCHEZ-DE-DIEGO C, PEDRAZZA L, PIMENTA-LOPES C, et al. NRF2 function in osteocytes is required for bone homeostasis and drives osteocytic gene expression. Redox Biol. 2021;40:101845. [103] SAKAI E, MORITA M, OHUCHI M, et al. Effects of deficiency of Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 on skeletal organization: a mechanism for diminished nuclear factor of activated T cells cytoplasmic 1 during osteoclastogenesis. FASEB J. 2017;31(9):4011-4022. [104] WEI Y, ZHANG S, SHAO F, et al. Ankylosing spondylitis: From pathogenesis to therapy. Int Immunopharmacol. 2025;145:113709. [105] ZOURIS G, EVANGELOPOULOS DS, BENETOS IS, et al. The Use of TNF-α Inhibitors in Active Ankylosing Spondylitis Treatment. Cureus. 2024;16(6):e61500. [106] CHEN Y, WU Y, FANG L, et al. METTL14-m6A-FOXO3a axis regulates autophagy and inflammation in ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Immunol. 2023;257:109838. [107] XU S, ZHANG X, MA Y, et al. FOXO3a Alleviates the Inflammation and Oxidative Stress via Regulating TGF-β and HO-1 in Ankylosing Spondylitis. Front Immunol. 2022;13:935534. [108] 沈瑞明, 李国铨, 郭峰. 血尿酸通过Keap1-Nrf2信号通路对强直性脊柱炎氧化应激作用机制研究[J]. 海南医学院学报,2020,26(10):771-774+781. [109] SONG C, WANG K, QIAN B, et al. Nrf-2/ROS/NF-κB pathway is modulated by cynarin in human mesenchymal stem cells in vitro from ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Transl Sci, 2024;17(3):e13748. |

| [1] |

Dong Chunyang, Zhou Tianen, Mo Mengxue, Lyu Wenquan, Gao Ming, Zhu Ruikai, Gao Zhiwei.

Action mechanism of metformin combined with Eomecon chionantha Hance dressing in treatment of deep second-degree burn wounds#br#

#br#

[J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(8): 2001-2013.

|

| [2] | Yang Xuetao, Zhu Menghan, Zhang Chenxi, Sun Yimin, Ye Ling. Applications and limitations of antioxidant nanomaterials in oral cavity [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(8): 2044-2053. |

| [3] | Chen Yulin, He Yingying, Hu Kai, Chen Zhifan, Nie Sha Meng Yanhui, Li Runzhen, Zhang Xiaoduo , Li Yuxi, Tang Yaoping. Effect and mechanism of exosome-like vesicles derived from Trichosanthes kirilowii Maxim. in preventing and treating atherosclerosis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(7): 1768-1781. |

| [4] | Liu Anting, Lu Jiangtao, Zhang Wenjie, He Ling, Tang Zongsheng, Chen Xiaoling. Regulation of AMP-activated protein kinase by platelet lysate inhibits cadmium-induced neuronal apoptosis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(7): 1800-1807. |

| [5] | Sun Yaotian, Xu Kai, Wang Peiyun. Potential mechanisms by which exercise regulates iron metabolism in immune inflammatory diseases [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(6): 1486-1498. |

| [6] | You Huijuan, Wu Shuzhen, Rong Rong, Chen Liyuan, Zhao Yuqing, Wang Qinglu, Ou Xiaowei, Yang Fengying. Macrophage autophagy in lung diseases: two-sided effects [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(6): 1516-1526. |

| [7] | Peng Zhiwei, Chen Lei, Tong Lei. Luteolin promotes wound healing in diabetic mice: roles and mechanisms [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(6): 1398-1406. |

| [8] | Jia Jinwen, Airefate·Ainiwaer, Zhang Juan. Effects of EP300 on autophagy and apoptosis related to allergic rhinitis in rats [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(6): 1439-1449. |

| [9] | Liu Kexin, , Hao Kaimin, Zhuang Wenyue, , Li Zhengyi. Autophagy-related gene expression in pulmonary fibrosis models: bioinformatic analysis and experimental validation [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(5): 1129-1138. |

| [10] | Hu Jing, Zhu Ling, Xie Juan, Kong Deying, Liu Doudou. Autophagy regulates early embryonic development in mice via affecting H3K4me3 modification [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(5): 1147-1155. |

| [11] | Wen Xiaolong, Weng Xiquan, Feng Yao, Cao Wenyan, Liu Yuqian, Wang Haitao. Effects of inflammation on serum hepcidin and iron metabolism related parameters in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(5): 1294-1301. |

| [12] | Yang Xiao, Bai Yuehui, Zhao Tiantian, Wang Donghao, Zhao Chen, Yuan Shuo. Cartilage degeneration in temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis: mechanisms and regenerative challenges [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(4): 926-935. |

| [13] | Dong Chao, Zhao Mohan, Liu Yunan, Yang Zeli, Chen Leqin, Wang Lanfang. Effects of magnetic nano-drug carriers on exercise-induced muscle injury and inflammatory response in rats [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(2): 345-353. |

| [14] | Feng Tao, Yin Zhaoyang. Biomechanical function and clinical significance of the lateral wall integrity in intertrochanteric fractures of the femur [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(15): 3960-3970. |

| [15] | Han Yapeng, Gao Jun, Niu Yunwei, Deng Enjia. Mechanism of programmed cell death mediated by total flavonoids of Rhizoma Drynariae [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(12): 3091-3099. |

| Viewed | ||||||

|

Full text |

|

|||||

|

Abstract |

|

|||||