Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research ›› 2019, Vol. 23 ›› Issue (1): 151-157.doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-4344.1533

Previous Articles Next Articles

Induced pluripotent stem cells in dental tissue regeneration: effect and application

Shao Miaomiao1, Liu Zhongxi1, Xu Nuo2, Liu Qinghua1, Wang Dong1, He Jianya1, Li Xiaojie1

- 1School of Stomatology, Dalian Medical University, Dalian 116044, Liaoning Province, China; 2Zhongshan College of Dalian Medical University, Dalian 116000, Liaoning Province, China

-

Revised:2018-09-17Online:2019-01-08Published:2018-11-28 -

Contact:Li Xiaojie, Master, Associate professor, School of Stomatology, Dalian Medical University, Dalian 116044, Liaoning Province, China -

About author:Shao Miaomiao, Master candidate, School of Stomatology, Dalian Medical University, Dalian 116044, Liaoning Province, China. Liu Zhongxi, Master candidate, School of Stomatology, Dalian Medical University, Dalian 116044, Liaoning Province, China. Shao Miaomiao and Liu Zhongxi contributed equally to this work. -

Supported by:the Project of Liaoning Provincial Department of Science and Technology, No. 201600752 (to LXJ)

CLC Number:

Cite this article

Shao Miaomiao, Liu Zhongxi, Xu Nuo, Liu Qinghua, Wang Dong, He Jianya, Li Xiaojie. Induced pluripotent stem cells in dental tissue regeneration: effect and application[J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2019, 23(1): 151-157.

share this article

Add to citation manager EndNote|Reference Manager|ProCite|BibTeX|RefWorks

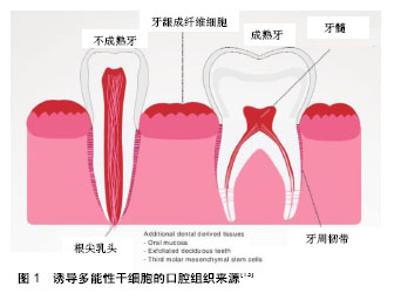

2.1 诱导多能性干细胞的定义和意义 诱导多能性干细胞是由成人体细胞通过一系列基因重编码过程获取的具有干细胞功能的细胞。诱导多能性干细胞的特性与胚胎干细胞类似,可以在特定条件下定向分化成多种细胞类型(如神经元、心脏、胰腺和肝细胞),因此诱导多能性干细胞可以替换受损或病变的组织,在再生医学领域有很好的应用前景[5]。且该技术不需要利用人类胚胎就可以获得大量成体多能干细胞,既跨越了伦理和法律难题,也不受细胞来源匮乏的困扰。自2006年问世以来,诱导多能性干细胞受到了极大的关注,对再生医学领域的发展具有革新性的意义,开启了再生医学研究的新途径。人类诱导多能性干细胞可分化为许多功能性细胞,并在疾病模型中显示出积极效应,如镰刀型细胞贫血病和帕金森综合征[6-8]。除了分化为治疗细胞外,Spence等[9]建立了一种稳定有效的方法诱导人体诱导多能性干细胞在体外分化成三维结构的肠组织。诱导多能性干细胞也是器官再生的种子模型。2013年,Takebe等[10]首次报道了通过移植体外培养的肝芽,利用诱导多能性干细胞细胞成功培育出人类的简单肝脏,且这些肝脏可以成功血管化并行使一定功能。牙齿也代表着一个良好的器官发生模型,它是由上皮和来自外胚层的间充质相互作用形成。与口腔来源的其他干细胞相比,诱导多能性干细胞优势显著。具体而言,诱导多能性干细胞可以从易采集的组织直接获得,如口腔黏膜组织等。此外,高度的易增殖活性使干细胞的获取变得简单,推动其在临床再生治疗方面的应用,成为口腔组织工程新的干细胞来源。 2.2 诱导多能性干细胞的来源 到目前为止,成纤维细胞依然是获取诱导多能性干细胞最常见的细胞来源,其不仅价格便宜,获取容易,还可以从公司购买,能在不同的研究领域得以应用。除成纤维细胞以外,还有其他比较容易获得的细胞类型,如血细胞、尿液中获得的脱落肾小管上皮细胞[11]、头发中的角质形成细胞及口腔来源的间充质样干细胞。限制诱导多能性干细胞发展的主要因素是其基因组的不稳定性和体内的成瘤倾向,来源细胞的特性能影响诱导多能性干细胞生成的效率和安全性。为了从体细胞中得到优良的诱导多能性干细胞,可以利用不同的细胞类型。总之,任何一个分化的体细胞都可以重新编程,不同细胞类型的分子特性可导致重编程效率的变化[12]。 口腔组织来源:虽然诱导多能性干细胞可以从许多成人组织中获取,但口腔组织获取方便简单,少有伦理争议,有独特的来源优势,例如口腔黏膜,牙龈组织,拔除的第三磨牙和乳牙[13],见图1。"

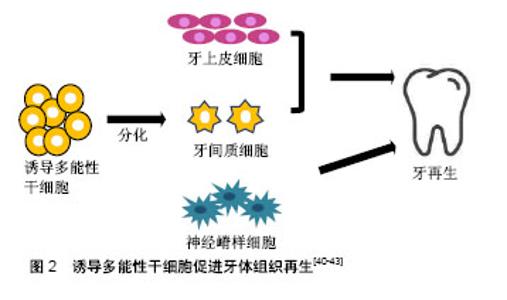

在牙髓、牙周韧带及根尖乳头来源的牙体组织本身就有大量的干细胞,可以直接去分化成诱导多能性干细胞。Yan等[14]将几种来源细胞进行比较,发现口腔来源的间充质样干细胞较其他体细胞相比(包皮成纤维细胞,皮肤成纤维细胞和成人间充质干细胞)能更有效地产生诱导多能性干细胞。此外,口腔来源的诱导多能性干细胞可能保持原始细胞的表观遗传记忆,在口腔组织再生过程中应用源组织来源的诱导多能性干细胞能促进其重新分化到原始细胞类型,提高诱导多能性干细胞分化成口腔组织的能力。许多口腔组织已成功用于生成诱导多能性干细胞,包括:牙龈成纤维细胞、周膜成纤维细胞、根尖乳头干细胞、牙髓干细胞、牙周膜干细胞、口腔黏膜、第三磨牙、脱落的乳牙及牙髓[15-20]。在细胞库的筛选过程中,牙髓细胞已被确定是诱导多能性干细胞的理想细胞来源,因为它很容易从患者拔除的第三磨牙中获取[21],且不论人类乳牙或恒牙牙髓细胞都能很好地诱导成诱导多能性干细胞[22]。牙髓也是治疗血管性疾病和儿童神经发育障碍的良好来源,且获取牙髓的过程具有无创性。Chen等[23]通过使用基因表达谱和RNA-seq进行调查,研究了牙髓对疾病模型的适用性,比较由乳牙牙髓诱导多能性干细胞(T-iPSC)制备的神经元和成纤维细胞诱导多能性干细胞(F-1PSC)制备的神经元的差异性。研究结果表明,来源于T-诱导多能性干细胞的神经元更适用于神经精神障碍,比F-诱导多能性干细胞更具优势。 除了上述最近常用的途径之外,利用颊细胞拭子以获取原始材料也是一个简单的方法。人类口腔黏膜是由表面的层状鳞状上皮和下面的连接组织构成。由于任何体细胞都可以重新编程,所以理论上可以使用从颊细胞拭子分离的细胞作为重编程的主要起始材料[24]。 其他组织来源:来自尿液的分离细胞大多是脱落的肾上皮细胞,在排尿过程中被排出。因此,在排尿过程中收集50-200 mL的尿液,经过连续洗涤和离心等步骤,即可在培养液中获得肾上皮细胞[25]。更确切地说,这些细胞是来自尿道的鳞状细胞并具有特定的上皮细胞表型。尿道细胞衍生的诱导多能性干细胞与胚胎干细胞或其他来源的诱导多能性干细胞显示出类似的表达。尿液的收集是一个无创性的过程,且不受年龄和性别的依赖,不需要特殊的医疗人员辅助完成。尿液来源的上皮细胞的重组效率为0.1%-4.0%,远高于成纤维细胞和血细胞,但是,细胞传代5次后的效率会降低[26]。使用角质形成细胞获得的诱导多能性干细胞则有许多改进并且缺点很少。角质形成细胞重编程速度快,在一两周,而成纤维细胞的持续时间为三四周。此外,角质细胞中C-MYC和KLF4的基因表达情况高于成纤维细胞,有利于重编程过程的高效进行[27]。人类的毛发是角质形成细胞的主要来源,如汗毛和头发,除了这两种类型之外,也包括胎儿或新生儿身体上的胎毛[28]。室温条件下,毛发可在DMEM培养基中培养数天,这也意味着它运输方便且不易丧失增殖活性。最近,Piao等[29]发现通过简单转染附加型载体能高效生成无融合的诱导多能性干细胞,这为今后角质形成细胞的广泛应用增加了更多可能性。此外,从免疫不成熟的新生儿脐血单核细胞生成的诱导多能性干细胞也具有重要应用价值。Wang等[30]优化现有的诱导多能性干细胞诱导方案,使用带有4个Yamanaka因子的dox诱导型慢病毒系统从脐血单核细胞中高效生成人类诱导多能性干细胞。脐血单核细胞衍生的诱导多能性干细胞(脐血-诱导多能性干细胞)具有与多能人胚胎干细胞相同的特征,可以加速基于细胞再生疗法的开发,使各种疾病患者受益。 2.3 诱导多能性干细胞的诱导条件 在重编程体细胞时,需要4种非常重要的转录因子,OCT4, KLF4,SOX2和C-MYC。除了转录因子,其他诱导条件在体细胞重编程和诱导多能性干细胞再分化中也发挥重要作用,如培养环境和诱导方式,它们共同影响诱导多能性干细胞的诱导效率和安全性。 培养环境:正常的肺部发育发生在1%-5%的低氧环境中。相反,体外胚胎干细胞和诱导多能性干细胞的分化通常在室内空气氧张力下进行。Garreta等[31]试图确定氧张力对小鼠人胚胎干细胞和诱导多能性干细胞衍生肺祖细胞的影响。结果表明,与空气氧气张力体积分数20%相比,体积分数5%的氧气张力可增强小鼠人胚胎干细胞和诱导多能性干细胞肺祖细胞的衍生。诱导多能性干细胞向视网膜细胞的有效分化是目前利用细胞疗法治疗各种失明的主要挑战。目前的分化策略是将诱导多能性干细胞置于体积分数20%的氧气中,并辅以一些可溶性生长因子,如DKK-1,Noggin和IGF-1。Bae等[32]模拟生理条件下的O2浓度(体积分数2%),研究人诱导诱导多能性干细胞和多能人胚胎干细胞产生视网膜祖细胞的效率变化。结果表明,生理条件下的O2浓度是诱导多能性干细胞和人胚胎干细胞高效产生视网膜祖细胞的有利条件。 转录因子及诱导载体诱导:与胚胎干细胞相比,诱导多能性干细胞易表现出遗传学和表观遗传学的异常。C-MYC和Klf4都是癌基因,病毒插入后有体内致瘤的风险,且诱导多能性干细胞易发生遗传学或表观遗传学的异常。虽然C-MYC在重编程过程中并非必不可少,但是它可以显著提高重编程的效率。因此,为了提高诱导多能性干细胞的安全性,减少体内致瘤的风险,Li等[33]尝试利用无C-MYC基因的方法诱导体细胞重新编程为诱导多能性干细胞,进而分化为肝细胞样细胞。Chang等[34]也使用C-MYC基因的方法将人牙髓细胞诱导为诱导多能性干细胞,进一步分化为神经元样细胞或用于缺血性血管疾病的治疗。 精氨酸甲基转移酶5(PRMT5)被认为在小鼠生殖细胞的表观遗传重编程中发挥重要作用。Chu等[35]发现PRMT5是一种在各种组织和不同年龄的睾丸中广泛表达的保守基因。与OCT3/4,SOX2,KLF4和c-Myc (POSKM)结合,过表达的PRMT5能显著提高碱性磷酸酶(AP)阳性诱导多能性干细胞样集落衍生的奶羊胚胎干细胞(GEFs)的数量,而且PRMT5的过表达能刺激奶羊胚胎干细胞的增殖,下调p53,p21和凋亡标记半胱氨酸天冬氨酸蛋白酶3的表达,提高体细胞重编程的效率。除了诱导基因,添加一些小分子化合物也能提高诱导率。Hou领导的研究小组发现,在使用7种小分子化合物的组合后,多能干细胞可以以高达0.2%的频率由小鼠体细胞产生[36]。在此之前,Esteban等[37]发现维生素C能提高诱导多能性干细胞的产生速度和效率,这为重编程过程的机制研究注入许多新的想法。该现象的部分原因可能是因为维生素C可以缓解细胞的衰老过程,此外,维生素C也能加速基因表达的变化并促进诱导多能性干细胞的前体细胞集落向完全重编程状态转变。在之后的研究中他们进一步发现,维生素C在重编程过程中诱导H3K36me2/3去甲基化,并鉴定了2种已知的维生素C依赖性H3K36去甲基化酶-KDM2A/2B,它们是重编程过程的潜在调节者[38]。最近,Hanna及其同事已经建立了确定的条件,以便利用化学混合物来促进人类原始多能干细胞的衍生[39]。 在产生诱导多能性干细胞的过程中,病毒整合载体的应用是造成基因组不稳定和成瘤倾向的主要因素。因此,许多研究组试图尝试使用非整合载体来减少诱导多能性干细胞基因组的不稳定性。Zhou等[40]在2012年成功地利用单个慢病毒“干细胞盒”从人根尖乳头的干细胞中产生诱导多能性干细胞。该“干细胞盒”两侧有lox-p位点,能编码4种人类重编程因子OCT4,SOX2,KLF4和c-MYC,允许其在cre-重组酶的帮助下进行有控制地切除。从生成的诱导多能性干细胞群中移除转基因/载体的能力为其潜在的医疗治疗应用提供了良好平台。 2.4 诱导多能性干细胞在口腔组织再生中的应用 近些年,诱导多能性干细胞在口腔组织再生领域的应用受到极大的关注,主要包括牙体组织的发育和再生,牙周软组织再生和牙槽骨的再生。但是,鉴于诱导多能性干细胞具有的潜在的致瘤性,未分化的诱导多能性干细胞是不适用于临床实践,越来越多的研究表明诱导多能性干细胞分化成更多限制性的细胞群是更安全的选择。 牙体组织的再生:牙齿的发育过程需要多种细胞的参与,如牙上皮细胞,牙间质细胞和神经嵴样细胞,而诱导多能性干细胞可以产生这些细胞群,当它们彼此结合时能促进牙齿生成,见图2。"

| [1] Hynes K, Gronthos S, Bartold PM. iPSC for dental tissue regeneration. Curr Oral Health Rep. 2014;1(1):9-15.[2] Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2007;2(12):3081-3089.[3] Maherali N, Sridharan R, Xie W, et al. Directly reprogrammed fibroblasts show global epigenetic remodeling and widespread tissue contribution. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1(1): 55-70.[4] Bar-Nur O, Russ H, Efrat S, et al. Epigenetic memory and preferential lineage-specific differentiation in induced pluripotent stem cells derived from human pancreatic islet beta cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9(1): 17-23.[5] Yamanaka S. Induced pluripotent stem cells: past, present, and future. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10(6):678-684.[6] Hargus G, Cooper O, Deleidi M, et al. Differentiated Parkinson patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells grow in the adult rodent brain and reduce motor asymmetry in Parkinsonian rats.Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(36):15921-15926.[7] Soldner F, Laganière J, Cheng AW, et al. Generation of isogenic pluripotent stem cells differing exclusively at two early onset Parkinson point mutations. Cell. 2011;146(2):318-331.[8] Sebastiano V, Maeder ML, Angstman JF, et al. In situ genetic correction of the sickle cell anemia mutation in human induced pluripotent stem cells using engineered zinc finger nucleases. Stem Cells. 2011;29(11):1717-1726.[9] Spence JR, Mayhew CN, Rankin SA, et al. Directed differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into intestinal tissue in vitro. Nature. 2011;470(7332):105-109.[10] Takebe T, Sekine K, Enomura M, et al. Vascularized and functional human liver from an iPSC-derived organ bud transplant. Nature. 2013;499(7459):481-484.[11] Wang L, Wang L, Huang W, et al. Generation of integration-free neural progenitor cells from cells in human urine. Nature Methods. 2013; 10(1):84-89. [12] Liebau S, Mahaddalkar PU, Kestler HA, et al. A hierarchy in reprogramming capacity in different tissue microenvironments: what we know and what we need to know. Stem Cells Dev. 2013; 22(5): 695-706.[13] Hynes K, Menichanin D, Bright R, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells: a new frontier for stem cells in dentistry. J Dent Res. 2015;94(11):1508.[14] Yan X, Qin H, Qu C, et al. iPS cells reprogrammed from human mesenchymal-like stem/progenitor cells of dental tissue origin. Stem Cells Dev. 2010;19(4):469.[15] Wada N, Wang B, Lin NH, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human gingival fibroblasts and periodontal ligament fibroblasts. J Periodont Res. 2011;46(4):438-447. [16] Oda Y, Yoshimura Y, Ohnishi H, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from human third molar mesenchymal stromal cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(38):29270-29278.[17] Nomura Y, Ishikawa M, Yashiro Y, et al. Human periodontal ligament fibroblasts are the optimal cell source for induced pluripotent stem cells. Histochem Cell Biol. 2012;137(6):719-732.[18] Beltrão-Braga PC, Pignatari GC, Maiorka PC, et al. Feeder-free derivation of induced pluripotent stem cells from human immature dental pulp stem cells. Cell Transplantation. 2011;20(11-12):1707. [19] Dambrot C, Van d PS, Van ZL, et al. Polycistronic lentivirus induced pluripotent stem cells from skin biopsies after long term storage, blood outgrowth endothelial cells and cells from milk teeth. Differentiation. 2013;85(3):101.[20] Miyoshi K, Tsuji D, Kudoh K, et al. Generation of human induced pluripotent stem cells from oral mucosa. J Biosci Bioeng. 2010; 110(3): 345-350.[21] Tamaoki N, Takahashi K, Tanaka T, et al. Dental pulp cells for induced pluripotent stem cell banking. J Dent Res. 2010;89(8):773-778.[22] Yoo CH, Na HJ, Lee DS, et al. Endothelial progenitor cells from human dental pulp-derived iPS cells as a therapeutic target for ischemic vascular diseases. Biomaterials. 2013;34(33):8149-8160.[23] Chen J, Lin M, Foxe JJ, et al. Transcriptome comparison of human neurons generated using induced pluripotent stem cells derived from dental pulp and skin fibroblasts. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e75682.[24] Warren L, Manos PD, Ahfeldt T, et al. Highly efficient reprogramming to pluripotency and directed differentiation of human cells with synthetic modified mRNA. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7(5):618.[25] Xue Y, Cai X, Wang L, et al. Generating a non-integrating human induced pluripotent stem cell bank from urine-derived cells. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e70573.[26] Zhou T, Benda C, Duzinger S, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from urine. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(7):1221-1228.[27] Linta L, Stockmann M, Kleinhans KN, et al. Rat embryonic fibroblasts improve reprogramming of human keratinocytes into induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21(6):965-976.[28] Gareri J, Koren G. Prenatal hair development: implications for drug exposure determination. Forensic Sci Int. 2010;196(1):27-31.[29] Piao Y, Hung SS, Lim S Y, et al. Efficient generation of integration-free human induced pluripotent stem cells from keratinocytes by simple transfection of episomal vectors. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2014; 3(7): 787-791.[30] Wang J, Gu Q, Hao J, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells with high efficiency from human umbilical cord blood mononuclear cells. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2013; 11(5): 304.[31] Garreta E, Melo E, Navajas D, et al. Low oxygen tension enhances the generation of lung progenitor cells from mouse embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells. Physiol Rep. 2014;2(7):e12075.[32] Bae D, Mondragonteran P, Hernandez D, et al. Hypoxia enhances the generation of retinal progenitor cells from human induced pluripotent and embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21(21):1344-1355.[33] Li HY, Chien Y, Chen YJ, et al. Reprogramming induced pluripotent stem cells in the absence of c-Myc for differentiation into hepatocyte-like cells. Biomaterials. 2011;32(26):5994.[34] Chang YC, Li WC, Twu NF, et al. Induction of dental pulp-derived induced pluripotent stem cells in the absence of c-Myc for differentiation into neuron-like cells. J Chin Med Assoc. 2014; 77(12): 618-625.[35] Chu Z, Niu B, Zhu H, et al. PRMT5 enhances generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from dairy goat embryonic fibroblasts via down-regulation of p53. Cell Proliferation. 2015;48(1):29.[36] Hou P, Li Y, Zhang X, et al. Pluripotent stem cells induced from mouse somatic cells by small-molecule compounds. Science. 2013;341(6146): 651-654.[37] Esteban MA, Wang T, Qin B, et al. Vitamin C enhances the generation of mouse and human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6(1):71.[38] Wang T, Chen K, Zeng X, et al. The histone demethylases jhdm1a/1b enhance somatic cell reprogramming in a Vitamin-C-dependent manner. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9(6):575-587.[39] Gafni O, Weinberger L, Mansour AA, et al. Corrigendum: derivation of novel human ground state naive pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2013; 504(7479):282.[40] Zou XY, Yang HY, Yu Z, et al. Establishment of transgene-free induced pluripotent stem cells reprogrammed from human stem cells of apical papilla for neural differentiation. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2012;3(5):43.[41] Li L, Wang Y, Lin M, et al. Augmented BMPRIA-mediated BMP signaling in cranial neural crest lineage leads to cleft palate formation and delayed tooth differentiation. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e66107.[42] Komada Y, Yamane T, Kadota D, et al. Origins and properties of dental, thymic, and bone marrow mesenchymal cells and their stem cells. PLoS One. 2011;7(11):e46436.[43] Rothová M, Peterková R, Tucker A S. Fate map of the dental mesenchyme: dynamic development of the dental papilla and follicle. DevBiol. 2012;366(2):244.[44] Otsu K, Kishigami R, Oikawa-Sasaki A, et al. Differentiation of induced pluripotent stem cells into dental mesenchymal cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21(7):1156.[45] Wen Y, Wang F, Zhang W, et al. Application of induced pluripotent stem cells in generation of a tissue-engineered tooth-like structure. Tissue EngPart A. 2012;18(15-16):1677.[46] Cai J, Zhang Y, Liu P, et al. Generation of tooth-like structures from integration-free human urine induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Regen (Lond). 2013;2(1):6.[47] Liu P, Zhang Y, Chen S, et al. Application of iPS cells in dental bioengineering and beyond. Stem Cell Rev. 2014;10(5):663-670.[48] Arakaki M, Ishikawa M, Nakamura T, et al. Role of epithelial-stem cell interactions during dental cell differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2012; 287(13):10590-601.[49] Ning F, Guo Y, Tang J, et al. Differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells into dental epithelial-like cells induced by ameloblasts serum-free conditioned medium. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;394(2):342.[50] Liu L, Liu Y, Zhang J, et al. Ameloblasts serum-free conditioned medium: bone morphogenic protein 4-induced odontogenic differentiation of mouse induced pluripotent stem cells. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2013;10(6):466-474.[51] Farooqi OA, Wehler CJ, Gibson G, et al. Appropriate recall interval for periodontal maintenance: a systematic review. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2015;15(4):171.[52] Chien KH, Chang YL, Wang M L, et al. Promoting induced pluripotent stem cell-driven biomineralization and periodontal regeneration in rats with maxillary-molar defects using injectable BMP-6 hydrogel. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):114..[53] Luo L, He Y, Wang X, et al. Potential roles of dental pulp stem cells in neural regeneration and repair. Stem Cells Int. 2018;2018:1731289.[54] Cheng PP, Liu XC, Ma PF, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells derived from induced pluripotent stem cells combined with low-dose rapamycin induced islet allograft tolerance via suppressing Th1 and enhancing regulatory T cell differentiation. Stem Cells Dev. 2015;24(15): 1793-1804.[55] Zhang J, Guan J, Niu X, et al. Exosomes released from human induced pluripotent stem cells-derived MSCs facilitate cutaneous wound healing by promoting collagen synthesis and angiogenesis. J Transl Med. 2015;13(1):49.[56] Hynes K, Menicanin D, Mrozik K, et al. Generation of functional mesenchymal stem cells from different induced pluripotent stem cell lines. Stem Cells Dev. 2014;23(10):1084-1096.[57] Hynes K, Menicanin D, Han J, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells from iPS cells facilitate periodontal regeneration. J Dent Res. 2013;92(9):833-839.[58] Egusa H, Kayashima H, Miura J, et al. Comparative analysis of mouse-induced pluripotent stem cells and mesenchymal stem cells during osteogenic differentiation in vitro. Stem Cells Dev. 2014;23(18): 2156-2169.[59] Illich DJ, Demir N, Stojkovi? M, et al. Concise review: induced pluripotent stem cells and lineage reprogramming: prospects for bone regeneration. Stem Cells. 2011;29(4):555-563.[60] Villadiaz LG, Brown SE, Liu Y, et al. Derivation of mesenchymal stem cells from human induced pluripotent stem cells cultured on synthetic substrates. Stem Cells. 2012;30(6):1174-1181.[61] Wei H, Tan G, Manasi, et al. One-step derivation of cardiomyocytes and mesenchymal stem cells from human pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Res. 2012;9(2):87.[62] Tang M, Chen W, Liu J, et al. Human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cell seeding on calcium phosphate scaffold for bone regeneration. Tissue Engineering Part A. 2014;20(7): 1295-1305.[63] Menendez L, Kulik M J, Page A T, et al. Directed differentiation of human pluripotent cells to neural crest stem cells. Nat Protoc. 2013; 8(1):203-212.[64] Okita K, Nagata N, Yamanaka S. Immunogenicity of induced pluripotent stem cells. Circ Res. 2011;109(7):720-721.[65] Araki R, Uda M, Hoki Y, et al. Negligible immunogenicity of terminally differentiated cells derived from induced pluripotent or embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2013;494(7435):100-104.[66] Guha P, Morgan J, Mostoslavsky G, et al. Lack of immune response to differentiated cells derived from syngeneic induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12(4):407-412. |

| [1] | Pu Rui, Chen Ziyang, Yuan Lingyan. Characteristics and effects of exosomes from different cell sources in cardioprotection [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(在线): 1-. |

| [2] | Lin Qingfan, Xie Yixin, Chen Wanqing, Ye Zhenzhong, Chen Youfang. Human placenta-derived mesenchymal stem cell conditioned medium can upregulate BeWo cell viability and zonula occludens expression under hypoxia [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(在线): 4970-4975. |

| [3] | Zhang Tongtong, Wang Zhonghua, Wen Jie, Song Yuxin, Liu Lin. Application of three-dimensional printing model in surgical resection and reconstruction of cervical tumor [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(9): 1335-1339. |

| [4] | Zhang Xiumei, Zhai Yunkai, Zhao Jie, Zhao Meng. Research hotspots of organoid models in recent 10 years: a search in domestic and foreign databases [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(8): 1249-1255. |

| [5] | Hou Jingying, Yu Menglei, Guo Tianzhu, Long Huibao, Wu Hao. Hypoxia preconditioning promotes bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells survival and vascularization through the activation of HIF-1α/MALAT1/VEGFA pathway [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 985-990. |

| [6] | Shi Yangyang, Qin Yingfei, Wu Fuling, He Xiao, Zhang Xuejing. Pretreatment of placental mesenchymal stem cells to prevent bronchiolitis in mice [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 991-995. |

| [7] | Liang Xueqi, Guo Lijiao, Chen Hejie, Wu Jie, Sun Yaqi, Xing Zhikun, Zou Hailiang, Chen Xueling, Wu Xiangwei. Alveolar echinococcosis protoscolices inhibits the differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells into fibroblasts [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 996-1001. |

| [8] | Fan Quanbao, Luo Huina, Wang Bingyun, Chen Shengfeng, Cui Lianxu, Jiang Wenkang, Zhao Mingming, Wang Jingjing, Luo Dongzhang, Chen Zhisheng, Bai Yinshan, Liu Canying, Zhang Hui. Biological characteristics of canine adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells cultured in hypoxia [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 1002-1007. |

| [9] | Geng Yao, Yin Zhiliang, Li Xingping, Xiao Dongqin, Hou Weiguang. Role of hsa-miRNA-223-3p in regulating osteogenic differentiation of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 1008-1013. |

| [10] | Lun Zhigang, Jin Jing, Wang Tianyan, Li Aimin. Effect of peroxiredoxin 6 on proliferation and differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells into neural lineage in vitro [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 1014-1018. |

| [11] | Zhu Xuefen, Huang Cheng, Ding Jian, Dai Yongping, Liu Yuanbing, Le Lixiang, Wang Liangliang, Yang Jiandong. Mechanism of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells differentiation into functional neurons induced by glial cell line derived neurotrophic factor [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 1019-1025. |

| [12] | Duan Liyun, Cao Xiaocang. Human placenta mesenchymal stem cells-derived extracellular vesicles regulate collagen deposition in intestinal mucosa of mice with colitis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 1026-1031. |

| [13] | Pei Lili, Sun Guicai, Wang Di. Salvianolic acid B inhibits oxidative damage of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and promotes differentiation into cardiomyocytes [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 1032-1036. |

| [14] | Guan Qian, Luan Zuo, Ye Dou, Yang Yinxiang, Wang Zhaoyan, Wang Qian, Yao Ruiqin. Morphological changes in human oligodendrocyte progenitor cells during passage [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 1045-1049. |

| [15] | Wang Zhengdong, Huang Na, Chen Jingxian, Zheng Zuobing, Hu Xinyu, Li Mei, Su Xiao, Su Xuesen, Yan Nan. Inhibitory effects of sodium butyrate on microglial activation and expression of inflammatory factors induced by fluorosis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 1075-1080. |

| Viewed | ||||||

|

Full text |

|

|||||

|

Abstract |

|

|||||