Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research ›› 2018, Vol. 22 ›› Issue (1): 152-157.doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-4344.0406

Previous Articles Next Articles

Melanoma stem cell markers and targeted therapies: awareness and pertinence

Wu Xing, Yuan Ding-fen

- Department of Dermatology, Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai 200233, China

-

Revised:2017-08-07Online:2018-01-08Published:2018-01-08 -

Contact:Yuan Ding-fen, Master, Chief physician, Department of Dermatology, Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai 200233, China -

About author:Wu Xing, Master, Physician, Department of Dermatology, Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai 200233, China

CLC Number:

Cite this article

Wu Xing, Yuan Ding-fen. Melanoma stem cell markers and targeted therapies: awareness and pertinence[J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2018, 22(1): 152-157.

share this article

Add to citation manager EndNote|Reference Manager|ProCite|BibTeX|RefWorks

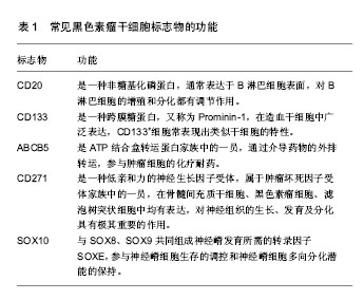

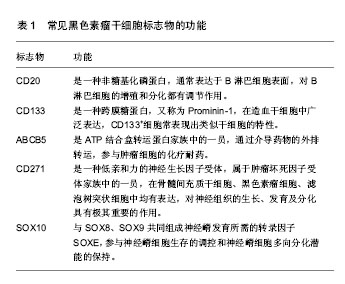

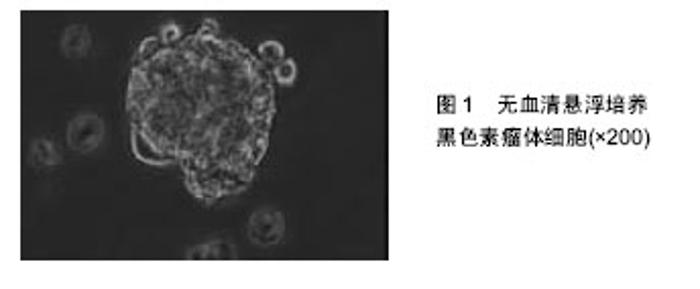

2.1 肿瘤干细胞 早在1867年就有人提出了肿瘤干细胞的概念,但是由于当时科学技术水平有限,未能分离出肿瘤干细胞。1977年在骨髓瘤细胞的体外软琼脂培养基克隆形成实验中,Hamhurger等[4]发现只有不到0.2%的细胞能形成克隆,不到4%的细胞能在NOD/SCID小鼠脾内形成肿瘤,有人提出将这小部分具有成瘤能力的细胞称为肿瘤干细胞。1997年,Bonnet等[5]首次从急性髓性白血病中分离出CD34+/CD38-表型细胞,且将其移植至NOD/SCID小鼠可以引起急性髓性白血病的发生,而其他细胞均不能引起急性髓性白血病的发生,从而证实了肿瘤干细胞的存在。2001年,Reya等[6]正式提出了肿瘤干细胞的概念。在肿瘤组织中存在着一小部分具有干细胞特性的肿瘤细胞亚群,它们具有自我更新能力以及多向分化潜能,在肿瘤的形成和生长过程中起着重要作用,称之为肿瘤干细胞[7]。 2.2 肿瘤干细胞的起源 肿瘤干细胞起源目前尚未完全清楚,大致有以下3种学说:①肿瘤干细胞来源于成体干细胞。致癌性的突变使得正常成体干细胞内自我更新及分化增殖的调控机制过度激活从而转变为肿瘤干细胞。Lenkiewicz等[8]证实脑肿瘤的肿瘤干细胞标志物CD133、nestin等与神经干细胞标志物相同。此外,部分乳腺癌的肿瘤干细胞表型也与其干细胞表型一致;②肿瘤干细胞来源于已分化的细胞(祖细胞甚至是终末分化细胞)。在外界因素的作用下,已分化的细胞可以去分化获得干细胞的特性,成为肿瘤干细胞。如转染MOZ-TIF2癌基因给祖细胞能够诱导产生急性髓性白血病;③肿瘤干细胞来源于细胞融合。Moore等[9]发现在慢性幽门螺杆菌感染的C57BL/6小鼠中,造血干细胞选择性地迁移至胃上皮,诱导胃癌的发生,说明肿瘤干细胞可能由正常的干细胞和突变的分化细胞融合产生。 2.3 肿瘤干细胞的分离 当前最常用的筛选和分离肿瘤干细胞的方法是通过其细胞表面标记物利用流式细胞分选术或磁性活化细胞分选术进行[10]。①流式细胞分选术,又称荧光活化细胞分选术,是利用ABCG2能够高效地将DNA荧光染料Hoechst33343泵出细胞外的特性,经流式细胞仪分选出Hoechst33343拒染的ABCG2高表达的侧群细胞。侧群细胞存在于大多数肿瘤细胞系中,拥有较强的生长繁殖能力并且具有多向分化潜能,因此不少研究者将侧群细胞作为部分肿瘤的肿瘤干细胞进行相关研究,如急性髓性白血病、脑肿瘤、前列腺癌、乳腺癌、肝癌、视网膜母细胞瘤等;②磁性活化细胞分选术,又称为免疫磁珠分选术,是利用磁珠免疫标记的特异性单克隆抗体与肿瘤干细胞表面特异性的抗原相结合,再在外部磁场的作用下,与特异性单克隆抗体结合的肿瘤干细胞经免疫磁珠吸附在磁式分选柱上,而未与特异性单克隆抗体结合的肿瘤干细胞则无法停留在磁场中,最后通过洗柱、收集,从而得到肿瘤干细胞。肺腺癌以及胶质瘤的肿瘤干细胞就是利用这种方法获得的。 2.4 黑色素瘤干细胞 随着对肿瘤干细胞相关研究的不断深入,人们在多种肿瘤组织和肿瘤细胞系中发现了肿瘤干细胞的存在,如乳腺癌、脑肿瘤、结肠癌等。Fang等在黑色素瘤中首次发现一种在胚胎干细胞培养基中表达CD20的无黏附力的球形细胞,其在一定的培养条件下可分化成黑素细胞、骨软骨形成细胞、脂肪形成细胞等多种细胞系,且在体外连续传代培养超过8个月后仍保持分化能力,说明其具有自我更新及多向分化潜能,被认为是黑色素瘤干细胞[11]。SCID/NOD小鼠实验也证实黑色素瘤干细胞具有较强的成瘤能力。与定位于毛囊隆突部位的黑素干细胞对比研究更进一步揭示了黑色素瘤干细胞的生物学特性,如黑素干细胞的标志物CD133在黑色素瘤干细胞中表达增加,提示它们之间存在一定的联系。文辉才等[12]利用无血清培养基培养人恶性黑色素瘤A375细胞系,获得黑色素瘤球体细胞(图1),其具有干细胞特性,迁移能力和致瘤能力强,高表达免疫标记CD20、CD133,说明恶性黑色素瘤存在肿瘤干细胞。"

| [1] Parmiani G.Melanoma Cancer Stem Cells: Markers and Functions.Cancers (Basel). 2016;8(3): E34.[2] Islam F, Qiao B, Smith RA, et al. Cancer stem cell: fundamental experimental pathological concepts and updates. Exp Mol Pathol. 2015;98(2):184-191.[3] Fang D, Nguyen TK, Leishear K, et al. A tumorigenic subpopulation with stem cell properties in melanomas. Cancer Res. 2005;65(20):9328-9337.[4] Hamburger AW, Salmon SE. Primary bioassay of human tumor stem cells. Science. 1977;197(4302):461-463.[5] Bonnet D, Dick JE. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nat Med. 1997;3(7):730-737.[6] Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, et al. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature. 2001;414(6859):105-111.[7] Shakhova O, Sommer L.Testing the cancer stem cell hypothesis in melanoma: the clinics will tell. Cancer Lett. 2013;338(1):74-81.[8] Lenkiewicz M, Li N, Singh SK. Culture and isolation of brain tumor initiating cells. Curr Protoc Stem Cell Biol. 2009; Chapter 3:Unit3.3. [9] Moore N, Houghton J, Lyle S. Slow-cycling therapy-resistant cancer cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21(10): 1822-1830.[10] Fulawka L, Donizy P, Halon A. Cancer stem cells--the current status of an old concept: literature review and clinical approaches. Biol Res. 2014;47:66.[11] Roesch A.Melanoma stem cells. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2015;13(2):118-124.[12] 文辉才,眭云鹏,简雪平,等.体外培养的人恶性黑色素瘤球体细胞干细胞特性观察[J].山东医药, 2016, 56(19):22-24.[13] Burgess R, Huang RP. Cancer Stem Cell Biomarker Discovery Using Antibody Array Technology. Adv Clin Chem. 2016;73:109-125.[14] Goede V, Klein C, Stilgenbauer S. Obinutuzumab (GA101) for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia and other B-cell non-hodgkin's lymphomas: a glycoengineered type II CD20 antibody. Oncol Res Treat. 2015;38(4):185-192.[15] Lee N, Barthel SR, Schatton T. Melanoma stem cells and metastasis: mimicking hematopoietic cell trafficking. Lab Invest. 2014;94(1):13-30.[16] Murphy GF, Wilson BJ, Girouard SD, et al. Stem cells and targeted approaches to melanoma cure. Mol Aspects Med. 2014;39:33-49.[17] Song H, Su X, Yang K, et al. CD20 Antibody-Conjugated Immunoliposomes for Targeted Chemotherapy of Melanoma Cancer Initiating Cells. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2015;11(11):1927-1946.[18] Roudi R, Korourian A, Shariftabrizi A, et al. Differential Expression of Cancer Stem Cell Markers ALDH1 and CD133 in Various Lung Cancer Subtypes. Cancer Invest. 2015;33(7):294-302.[19] Roudi R, Ebrahimi M, Sabet MN, et al. Comparative gene-expression profiling of CD133(+) and CD133(-) D10 melanoma cells. Future Oncol. 2015;11(17):2383-2393.[20] Zimmerer RM, Matthiesen P, Kreher F, et al. Putative CD133+ melanoma cancer stem cells induce initial angiogenesis in vivo. Microvasc Res. 2016;104:46-54.[21] Madjd Z, Erfani E, Gheytanchi E, et al. Expression of CD133 cancer stem cell marker in melanoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis.Int J Biol Markers. 2016;31(2): e118-125.[22] Rajabi Fomeshi M, Ebrahimi M, Mowla SJ, et al. CD133 Is Not Suitable Marker for Isolating Melanoma Stem Cells from D10 Cell Line. Cell J. 2016;18(1):21-27.[23] Lutz NW, Banerjee P, Wilson BJ, et al. Expression of Cell-Surface Marker ABCB5 Causes Characteristic Modifications of Glucose, Amino Acid and Phospholipid Metabolism in the G3361 Melanoma-Initiating Cell Line. PLoS One. 2016;11(8):e0161803.[24] Ma J, Lin JY, Alloo A, et al. Isolation of tumorigenic circulating melanoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;402(4):711-717.[25] Wilson BJ, Saab KR, Ma J, et al. ABCB5 maintains melanoma-initiating cells through a proinflammatory cytokine signaling circuit. Cancer Res. 2014;74(15): 4196-4207.[26] Civenni G, Walter A, Kobert N, et al. Human CD271-positive melanoma stem cells associated with metastasis establish tumor heterogeneity and long-term growth. Cancer Res. 2011;71(8):3098-3109.[27] Redmer T, Welte Y, Behrens D, et al. The nerve growth factor receptor CD271 is crucial to maintain tumorigenicity and stem-like properties of melanoma cells. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e92596.[28] Cheli Y, Bonnazi VF, Jacquel A, et al. CD271 is an imperfect marker for melanoma initiating cells. Oncotarget. 2014; 5(14):5272-5283.[29] Buonaccorsi JN, Prieto VG, Torres-Cabala C, et al. Diagnostic utility and comparative immunohistochemical analysis of MITF-1 and SOX10 to distinguish melanoma in situ and actinic keratosis: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 70 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36(2):124-130.[30] Graf SA, Busch C, Bosserhoff AK, et al. SOX10 promotes melanoma cell invasion by regulating melanoma inhibitory activity. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134(8):2212-2220.[31] Shakhova O, Zingg D, Schaefer SM, et al. Sox10 promotes the formation and maintenance of giant congenital naevi and melanoma. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14(8):882-890.[32] Willis BC, Johnson G, Wang J, et al. SOX10: a useful marker for identifying metastatic melanoma in sentinel lymph nodes. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2015; 23(2):109-112.[33] Rappa G, Fodstad O, Lorico A. The stem cell-associated antigen CD133 (Prominin-1) is a molecular therapeutic target for metastatic melanoma. Stem Cells. 2008;26(12): 3008-3017.[34] Schatton T, Schütte U, Frank NY, et al. Modulation of T-cell activation by malignant melanoma initiating cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70(2):697-708.[35] Regad T. Molecular and cellular pathogenesis of melanoma initiation and progression. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70(21): 4055-4065.[36] Santini R, Vinci MC, Pandolfi S, et al. Hedgehog-GLI signaling drives self-renewal and tumorigenicity of human melanoma-initiating cells. Stem Cells. 2012;30(9): 1808-1818.[37] Onisim A, Achimas-Cadariu A, Vlad C, et al. Current insights into the association of Nestin with tumor angiogenesis. J BUON. 2015;20(3):699-706.[38] 李崇鑫,宋鑫.黑素瘤干细胞样细胞及其靶向治疗研究进展[J].中国肿瘤生物治疗杂志,2016,23(1):124-129.[39] Hirsch HA, Iliopoulos D, Struhl K. Metformin inhibits the inflammatory response associated with cellular transformation and cancer stem cell growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(3):972-977.[40] CSCO黑色素瘤专家委员会.中国黑色素瘤诊疗指南(2011版)[J].临床肿瘤学杂志,2012,17(2):159-171. |

| [1] | Zhang Tongtong, Wang Zhonghua, Wen Jie, Song Yuxin, Liu Lin. Application of three-dimensional printing model in surgical resection and reconstruction of cervical tumor [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(9): 1335-1339. |

| [2] | Zeng Yanhua, Hao Yanlei. In vitro culture and purification of Schwann cells: a systematic review [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 1135-1141. |

| [3] | Xu Dongzi, Zhang Ting, Ouyang Zhaolian. The global competitive situation of cardiac tissue engineering based on patent analysis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(5): 807-812. |

| [4] | Wu Zijian, Hu Zhaoduan, Xie Youqiong, Wang Feng, Li Jia, Li Bocun, Cai Guowei, Peng Rui. Three-dimensional printing technology and bone tissue engineering research: literature metrology and visual analysis of research hotspots [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(4): 564-569. |

| [5] | Chang Wenliao, Zhao Jie, Sun Xiaoliang, Wang Kun, Wu Guofeng, Zhou Jian, Li Shuxiang, Sun Han. Material selection, theoretical design and biomimetic function of artificial periosteum [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(4): 600-606. |

| [6] | Liu Fei, Cui Yutao, Liu He. Advantages and problems of local antibiotic delivery system in the treatment of osteomyelitis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(4): 614-620. |

| [7] | Li Xiaozhuang, Duan Hao, Wang Weizhou, Tang Zhihong, Wang Yanghao, He Fei. Application of bone tissue engineering materials in the treatment of bone defect diseases in vivo [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(4): 626-631. |

| [8] | Zhang Zhenkun, Li Zhe, Li Ya, Wang Yingying, Wang Yaping, Zhou Xinkui, Ma Shanshan, Guan Fangxia. Application of alginate based hydrogels/dressings in wound healing: sustained, dynamic and sequential release [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(4): 638-643. |

| [9] | Chen Jiana, Qiu Yanling, Nie Minhai, Liu Xuqian. Tissue engineering scaffolds in repairing oral and maxillofacial soft tissue defects [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(4): 644-650. |

| [10] | Xing Hao, Zhang Yonghong, Wang Dong. Advantages and disadvantages of repairing large-segment bone defect [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(3): 426-430. |

| [11] | Chen Siqi, Xian Debin, Xu Rongsheng, Qin Zhongjie, Zhang Lei, Xia Delin. Effects of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and human umbilical vein endothelial cells combined with hydroxyapatite-tricalcium phosphate scaffolds on early angiogenesis in skull defect repair in rats [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(22): 3458-3465. |

| [12] | Wang Hao, Chen Mingxue, Li Junkang, Luo Xujiang, Peng Liqing, Li Huo, Huang Bo, Tian Guangzhao, Liu Shuyun, Sui Xiang, Huang Jingxiang, Guo Quanyi, Lu Xiaobo. Decellularized porcine skin matrix for tissue-engineered meniscus scaffold [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(22): 3473-3478. |

| [13] | Mo Jianling, He Shaoru, Feng Bowen, Jian Minqiao, Zhang Xiaohui, Liu Caisheng, Liang Yijing, Liu Yumei, Chen Liang, Zhou Haiyu, Liu Yanhui. Forming prevascularized cell sheets and the expression of angiogenesis-related factors [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(22): 3479-3486. |

| [14] | Liu Chang, Li Datong, Liu Yuan, Kong Lingbo, Guo Rui, Yang Lixue, Hao Dingjun, He Baorong. Poor efficacy after vertebral augmentation surgery of acute symptomatic thoracolumbar osteoporotic compression fracture: relationship with bone cement, bone mineral density, and adjacent fractures [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(22): 3510-3516. |

| [15] | Liu Liyong, Zhou Lei. Research and development status and development trend of hydrogel in tissue engineering based on patent information [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(22): 3527-3533. |

| Viewed | ||||||

|

Full text |

|

|||||

|

Abstract |

|

|||||