Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research ›› 2026, Vol. 30 ›› Issue (17): 4377-4389.doi: 10.12307/2026.148

Previous Articles Next Articles

Intervention effect and mechanism of Compound Herba Gueldenstaedtiae in a mouse model of breast hyperplasia

Wu Yilin1, Tian Hongying1, Sun Jiale1, Jiao Jiajia1, Zhao Zihan1, Shao Jinhuan1, Zhao Kaiyue1, Zhou Min1, Li Qian1, 2, Li Zexin1, Yue Changwu1

- 1Yan’an Key Laboratory of Microbial Drug Innovation and Transformation, School of Basic Medicine, Yan’an University, Yan’an 716000, Shaanxi Province, China; 2Department of Clinical Laboratory, Affiliated Hospital of Yan’an University, Yan’an 716000, Shaanxi Province, China

-

Received:2025-04-04Accepted:2025-08-13Online:2026-06-18Published:2025-12-01 -

Contact:Li Qian, Associate chief technician, Yan’an Key Laboratory of Microbial Drug Innovation and Transformation, School of Basic Medicine, Yan’an University, Yan’an 716000, Shaanxi Province, China; Department of Clinical Laboratory, Affiliated Hospital of Yan’an University, Yan’an 716000, Shaanxi Province, China Co-corresponding author: Li Zexin, MS, Yan’an Key Laboratory of Microbial Drug Innovation and Transformation, School of Basic Medicine, Yan’an University, Yan’an 716000, Shaanxi Province, China Co-corresponding author: Yue Changwu, PhD, Professor, Doctor’s supervisor, Yan’an Key Laboratory of Microbial Drug Innovation and Transformation, School of Basic Medicine, Yan’an University, Yan’an 716000, Shaanxi Province, China -

About author:Wu Yilin, MS, Yan’an Key Laboratory of Microbial Drug Innovation and Transformation, School of Basic Medicine, Yan’an University, Yan’an 716000, Shaanxi Province, China Tian Hongying, MS, professor, Yan’an Key Laboratory of Microbial Drug Innovation and Transformation, School of Basic Medicine, Yan’an University, Yan’an 716000, Shaanxi Province, China Wu Yilin and Tian Hongying contributed equally to this work. -

Supported by:Yan’an Science and Technology Program, No. 2024-SFGG-201; Shaanxi Provincial Natural Science Program, No. 2024JC-YBMS-755

CLC Number:

Cite this article

Wu Yilin, Tian Hongying, Sun Jiale, Jiao Jiajia, Zhao Zihan, Shao Jinhuan, Zhao Kaiyue, Zhou Min, Li Qian, Li Zexin, Yue Changwu. Intervention effect and mechanism of Compound Herba Gueldenstaedtiae in a mouse model of breast hyperplasia[J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(17): 4377-4389.

share this article

Add to citation manager EndNote|Reference Manager|ProCite|BibTeX|RefWorks

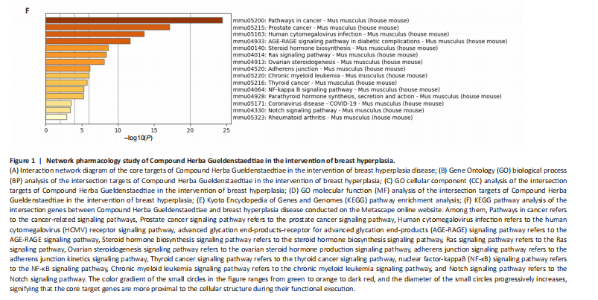

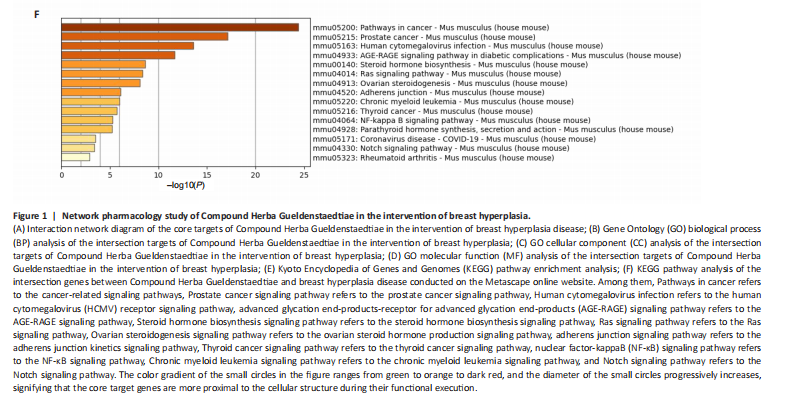

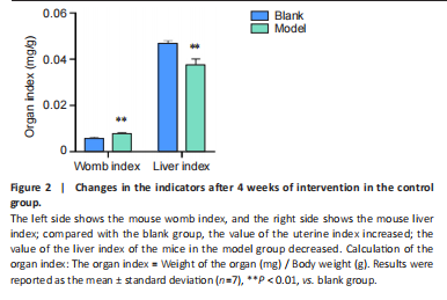

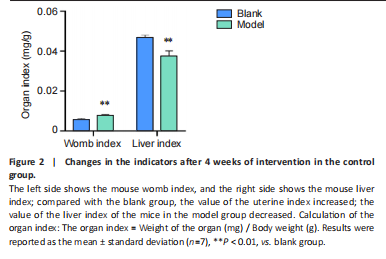

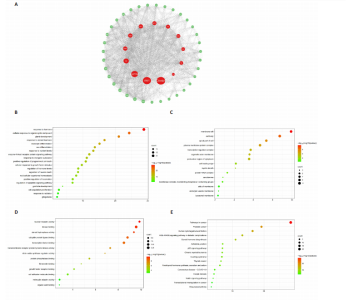

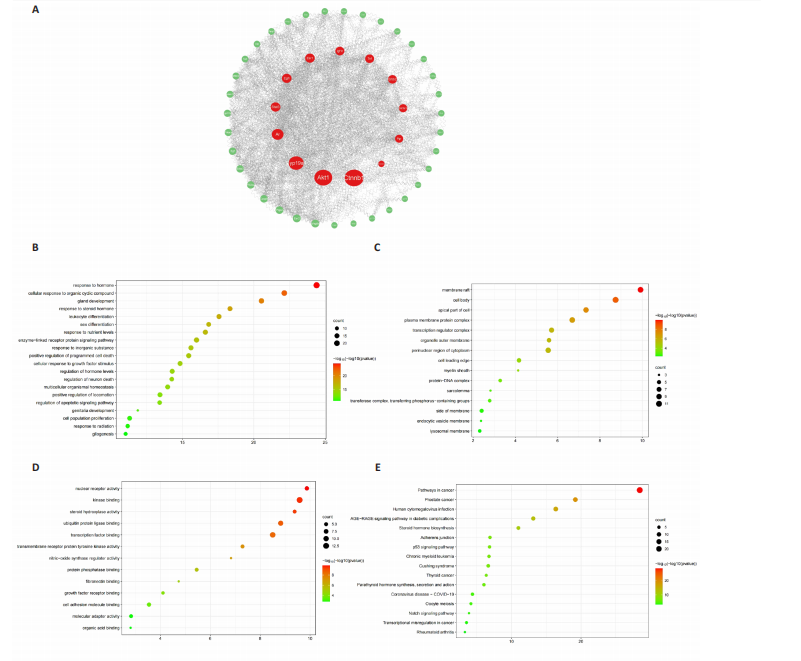

Analysis of the number of experimental animals A total of 65 mice were included in the experiment. Among them, 63 mice were included in the result analysis. Two mice died due to stress reactions and inability to adapt to the environment. Finally, 63 mice were left for the statistical result analysis. The KEGG signaling pathway prediction for the compound Herba Gueldenstaedtiae in treating breast hyperplasia According to the screening criteria of active ingredients and action targets, a total of 46 active ingredients and 1 213 action targets of Compound Herba Gueldenstaedtiae were collected. By finding the intersection genes between Compound Herba Gueldenstaedtiae and breast hyperplasia, it was discovered that 50 genes were related to breast hyperplasia. Then, the top 30 target genes with the highest degree values among the intersection genes were imported into the Cytoscape 3.6.0 software to draw a PPI network diagram (Figure 1A). It was found that Phenyl phenylacetate, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, cyclohexanone, protocatechuate, and methyl 2-(4-(hydroxymethyl) phenyl) acetate were the five nodes with relatively large degree values. This indicates that these proteins play an important role in the PPI network and may be the key targets for Compound Herba Gueldenstaedtiae in treating breast hyperplasia. The biological processes, cellular components, and molecular functions of the intersection targets were analyzed using Metascape. The results showed that in terms of biological processes, it was mainly manifested as the cell’s response to hormones, response to organic cyclic compounds, gland development, and response to inorganic substances (Figure 1B). For cellular components, it was mainly manifested as membrane rafts, the apical part of the cell, plasma membrane protein complex, transcriptional regulatory complex, and the perinuclear region of the cytoplasm (Figure 1C). For molecular functions, it was mainly manifested as nuclear receptor activity, steroid hydroxylase activity, protein phosphatase binding, and cell adhesion molecule binding (Figure 1D). A KEGG pathway enrichment analysis was carried out on the intersection genes (Figure 1E). The Metascape online website was used to conduct a KEGG pathway analysis on the intersection genes between Compound Herba Gueldenstaedtiae and breast hyperplasia disease (Figure 1F), and 15 important pathways related to the intervention of breast hyperplasia by Compound Herba Gueldenstaedtiae were predicted. The results showed that the targets were mainly enriched in cancer-related signaling pathways, prostate cancer signaling pathways, Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) receptor signaling pathways, advanced glycation end-products-receptor for advanced glycation end-products (AGE-RAGE) signaling pathways, and Ras signaling pathways. Most of these pathways are related to inflammation, suggesting that Compound Herba Gueldenstaedtiae may intervene in breast hyperplasia by inhibiting inflammatory signaling pathways. The active ingredients of Compound Herba Gueldenstaedtiae may participate in biological processes such as hormone regulation, cell proliferation, and differentiation through these potential targets, affecting the physiological activities of cells. At the same time, based on the results of the KEGG pathway enrichment analysis, it is speculated that this compound may reduce the stimulation of the breast tissue by inflammatory reactions through inhibiting inflammatory signaling pathways, thereby intervening in the development of breast hyperplasia. Establishment of a mouse model of breast hyperplasia The model of breast hyperplasia was tested by changes in organ indexes After estrogen modeling, the organs of the female mice exhibited changes. Specifically, the uterine index value increased when compared to the blank group. Conversely, the liver index of the mice in the model group decreased (Figure 2), suggesting that the model was successfully established."

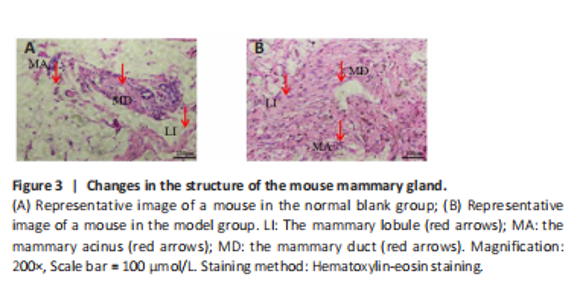

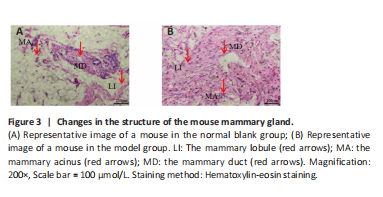

Use of hematoxylin-eosin staining to verify the breast hyperplasia model After the intervention, mice with mammary gland hyperplasia were selected for pathological tissue sectioning, and the results were observed under a microscope (Figure 3). The number of mammary glands and lobules in the model group increased, ducts dilated, and breast tissue extensively proliferated. Confirmed the successful establishment of a mouse mammary gland hyperplasia model. The combined injection of estrogen and progesterone disrupts the hormonal balance in mice. Estrogen stimulates the growth of mammary ducts and acini, while progesterone promotes the development of mammary lobules. Excessive amounts of both hormones lead to abnormal hyperplasia of the mammary tissue. At the same time, the hormonal changes affect the physiological functions of the uterus and liver, which are reflected in the changes of the organ indices. This indicates a close relationship between hormonal imbalance, breast hyperplasia, and changes in organ functions."

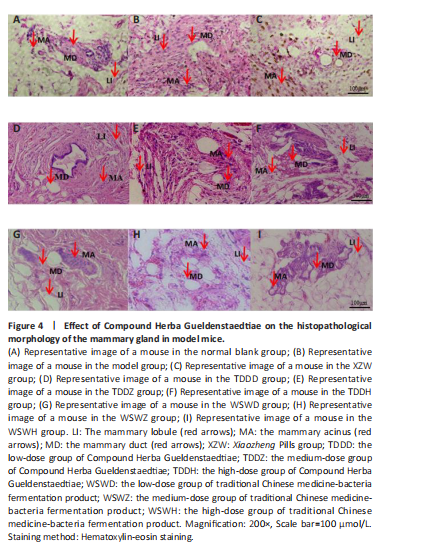

Effect of traditional Chinese medicine compound Herba Gueldenstaedtiae on pathological morphology of mammary gland tissue in mice with breast hyperplasia After 30 days of drug administration, the pathological morphology of mammary tissue in each group revealed distinct differences. The blank group exhibited normal mammary duct size, with scattered and sparse mammary lobules containing a small number of acini, and no evidence of diffuse hyperplasia (Figure 4A). In contrast, the model group displayed a significant increase in the number and volume of mammary lobules, diffuse hyperplasia, an increased number of acini, and abnormally enlarged mammary ducts compared with the blank group (Figure 4B). The XZW group exhibited a notable decrease in the count of mammary lobules and acini, a diminution in ductal orifice dimensions, and a substantial enhancement in the severity of hyperplasia (Figure 4C). Mice treated with compound Herba Gueldenstaedtiae water at varying doses exhibited a decrease in the number of mammary lobules and acini, as well as a reduction in mammary duct orifice size. The improvement in diffuse hyperplasia of mammary tissue increased with the escalation of drug dose (Figure 4D–F). Similarly, mice treated with microbial fermentation compound drugs at low, medium, and high doses demonstrated a decreased number of mammary lobules and acini, reduced ductal orifice size, and an enhanced improvement in diffuse hyperplasia of mammary gland tissue with increasing drug dose (Figure 4G–I). These findings confirm that both methods of treatment with compound Herba Gueldenstaedtiae can effectively ameliorate mammary gland hyperplasia in mice. The Compound Herba Gueldenstaedtiae and its microbial fermentation products may improve the pathological morphology of the mammary tissue by regulating the hormone levels and inhibiting the excessive proliferation of mammary epithelial cells. The effect of the high-dose group is more significant. It may be because a higher dose can more effectively regulate the relevant signaling pathways, inhibit the cell proliferation signals, and promote the normal differentiation of cells, thus alleviating breast hyperplasia."

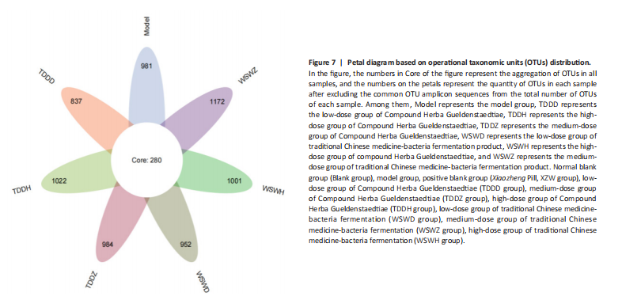

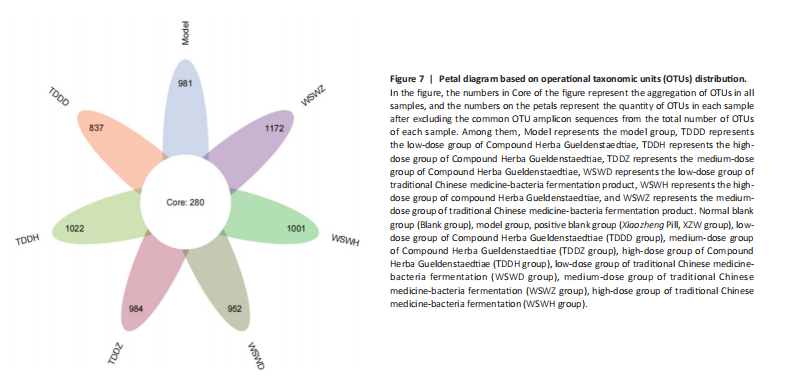

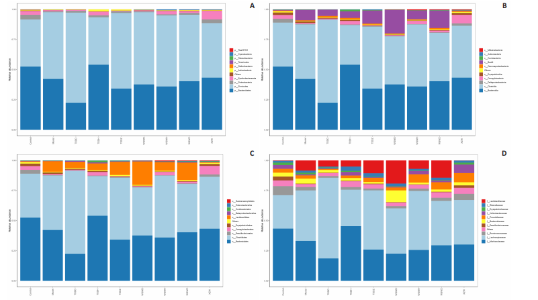

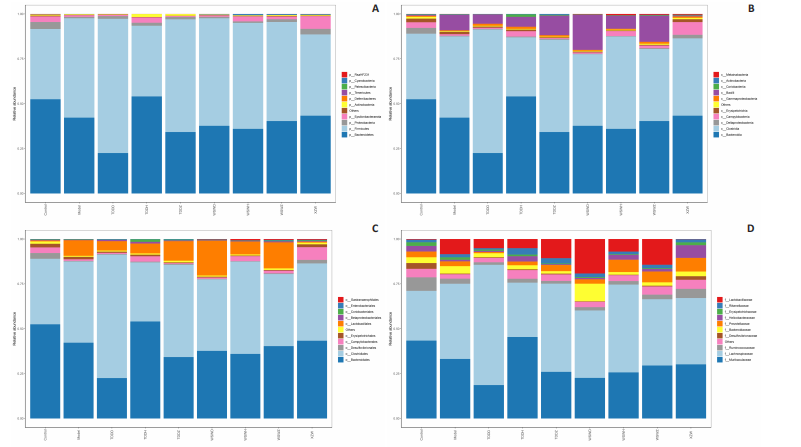

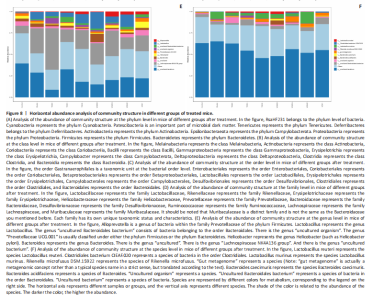

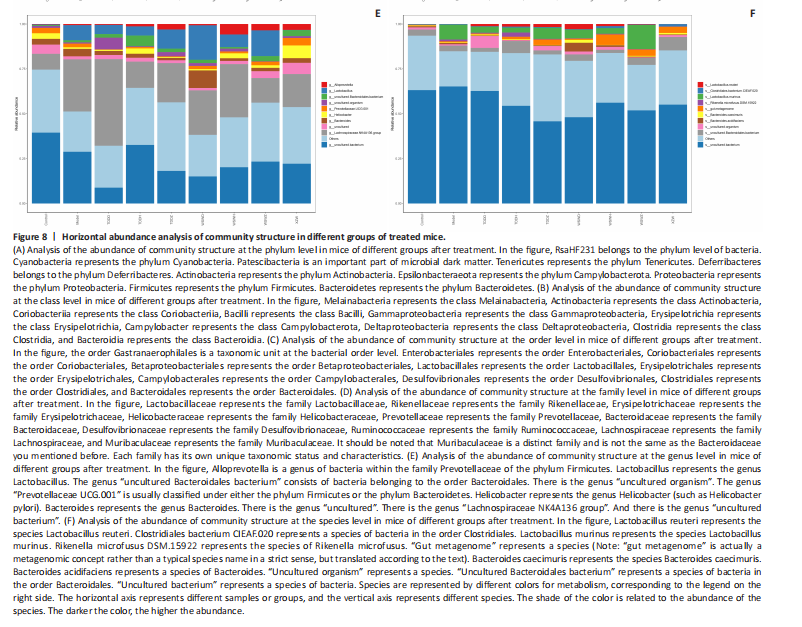

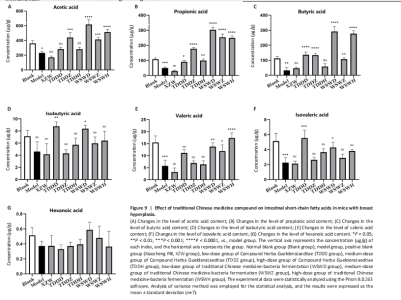

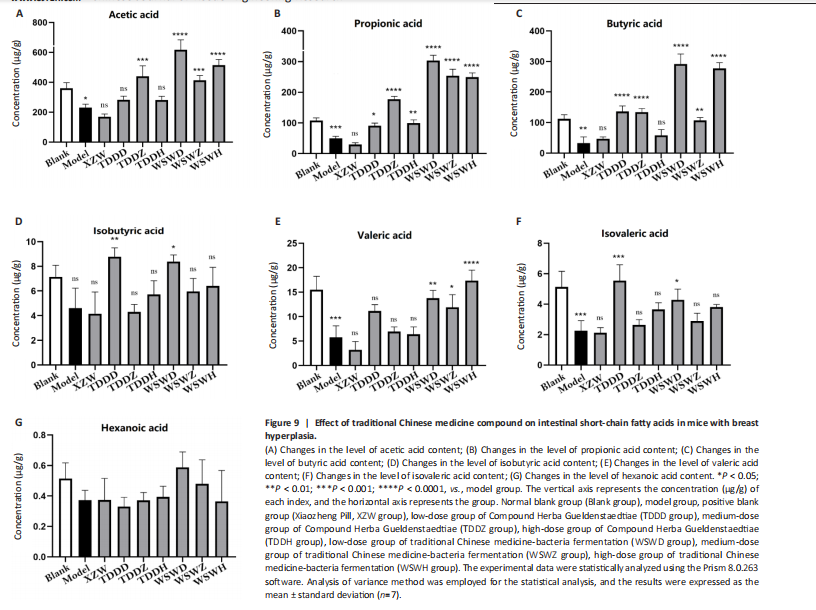

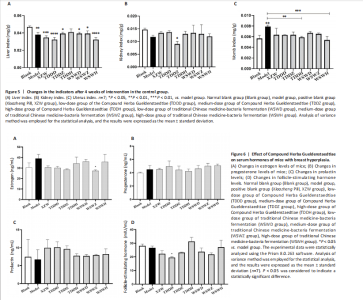

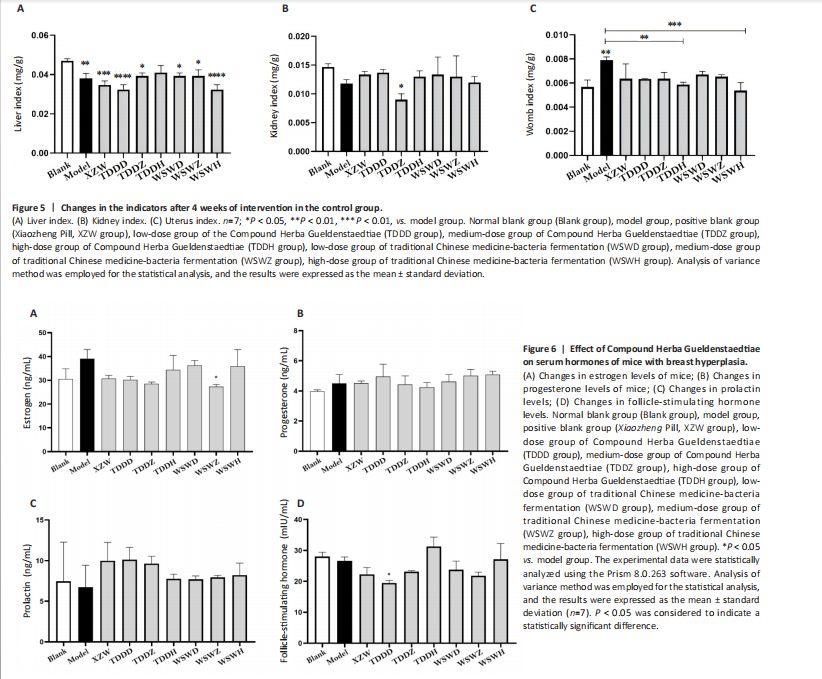

Detection of organ index in mice Figure 5 shows that compared to the blank group, the model group has a higher uterine index, followed by a higher liver index. After intervention, except for the TDDH group, the liver index of the blank group contracted when parallel (Figure 5A). Compared with the Blank group, the renal index of the TDDZ group decreased (P < 0.05), while there were no abnormalities in the other groups (Figure 5B). In contrast to the model group, the uterine index decreased in both the TDDH and WSWH groups (P < 0.01 in the TDDH group and P < 0.001 in the WSWH group). No abnormalities were found in the other intervention groups (Figure 5C), indicating that the TDDH and WSWH groups had uterine damage during the intervention period for breast hyperplasia. The results indicate that the two different treatment methods of Compound Herba Gueldenstaedtiae have certain effects on the uterus and liver; However, there are differences in organ index, which hinders its comprehensive application as a therapeutic agent for mice. The establishment of the breast hyperplasia model leads to hormonal imbalance, affecting the normal functions of the uterus and liver and causing changes in their indices. After drug intervention, there are differences in the effects of each dosage group on different organs, which may be due to the different metabolism and action targets of the active ingredients of the drugs in the body. For example, certain ingredients may preferentially act on the liver, regulating the metabolic function of the liver, thereby reducing the liver index; while the effect on the uterus may be related to hormonal regulation. By regulating the levels of estrogen and progesterone, it affects the growth and development of the uterus. Effect of Compound Herba Gueldenstaedtiae on serum hormone levels in mice with breast hyperplasia Hormone levels (estrogen, progesterone, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and prolactin) in the serum of mice with breast hyperplasia were measured using ELISA (Figure 6). There was no statistically difference in estrogen levels between the model and blank groups (P > 0.05). In contrast to the model group, there was no significant variation in estrogen levels among the positive blank (XZW group), TDDD, TDDZ, TDDH, WSWD and WSWH groups (P > 0.05). Notably, the estrogen level in the WSWZ group was significantly lower than that in the model group (P < 0.05) (Figure 6A). No evident difference in progesterone levels was examined between the model and blank groups (P > 0.05). Similarly, no diversity in progesterone levels were found among the positive blank (XZW group), TDDD, TDDH, WSWD, WSWZ and WSWH groups compared with the model group (P > 0.05) (Figure 6B). There was no obviously disparity in prolactin levels between the model and blank groups (P > 0.05). Similarly, patentably Indistinctness in prolactin levels were discerned among the positive blank (XZW group), TDDD, TDDH, WSWD, WSWZ and WSWH groups compared with the model group (P > 0.05) (Figure 6C). No evident variation in FSH levels was examined between the model and blank groups (P > 0.05). No evident disparity in estrogen levels were found among the positive blank (XZW group), TDDZ, TDDH, WSWD, WSWZ and WSWH groups compared with the model group (P > 0.05). Conversely, the estrogen level in the TDDD group was significantly lower than that in the model group (P < 0.05) (Figure 6D). These findings suggest that the TDDD group may decrease FSH levels in mice with breast hyperplasia, while the medium dose of compound sweetener may reduce estrogen levels in these mice. The balance of hormone levels is crucial for the normal development and functional maintenance of mammary gland tissues. The Compound Herba Gueldenstaedtiae may affect the secretion and metabolism of hormones by regulating the function of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. The low-dose water extract of Herba Gueldenstaedtiae reduces the level of FSH, likely through a feedback regulation mechanism that decreases the secretion of FSH by the pituitary gland. The medium-dose microbial fermentation group reduces the level of estrogen, possibly by influencing the synthesis or metabolic process of estrogen, thereby affecting the development of breast hyperplasia. Effect of compound Herba Gueldenstaedtiae on intestinal flora in mice with breast hyperplasia In order to test the species composition diversity within each sample group, based on the results of OTUs clustering analysis and research requirements, the common and unique OTUs among different samples (groups) were analyzed. When the number of samples (groups) is greater than 5, a petal diagram is drawn. It can intuitively show the number of OTUs contained in each group and obtain the number of OTU intersections shared by all groups. The results are as follows. The number of OTUs contained in each group is 981 in the model group, 837 in the TDDD group, 984 in the TDDZ group, 1 022 in the TDDH group, 952 in the WSWD group, 1 172 in the WSWZ group, and 1001 in the WSWH group. The number of OTU intersections is 280. The above results indicate that there are differences in abundance among the groups and they are also interrelated. After drug administration, the types of intestinal flora in mice increased, suggesting that Compound Herba Gueldenstaedtiae can regulate the diversity of the intestinal microbiota in the mouse model of mammary gland hyperplasia (Figure 7). Analysis of intestinal flora structure of mice in each group after different drug intervention Based on the Species annotation results for each group of samples, the relative abundance of species at various taxonomic levels (Family, Phylum, Class, Order, Genus, and Species) was ascertained. Figure 8 reveals that, at the phylum level (Figure 8A), the intestinal community structure of mice in all groups was predominantly characterized by Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes. In comparison to the blank group, Bacteroidetes diminished while Firmicutes expanded in the model group. Contrasting with the model group, the abundance of Firmicutes escalated in all experimental groups except the TDDH group; notably, the proportions of Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes in the TDDH group resembled those of the blank group. These findings indicate a decrease in Bacteroidetes and an increase in Firmicutes in mice with breast hyperplasia. Following high-dose administration of the Compound Herba Gueldenstaedtiae water decoction, Bacteroidetes levels were restored while Firmicutes decreased, thus ameliorating the dysbiosis induced by breast hyperplasia. At the class level, the intestinal flora structure and distribution among all mouse groups showed that the dominant classes were Clostridia and Bacteroidetes (Figure 8B). Compare with the model group, the TDDH group showed an increase in Bacteroidetes and a decrease in Clostridia. Conversely, the other experimental groups displayed contrasting trends. The TDDH group’s Bacteroidetes and Clostridia proportions were nearly identical to those of the blank group. These outcomes suggest that high-dose treatment with the compound SGD can reverse the decline in Bacteroidetes and the rise in Clostridia associated with breast hyperplasia in mice. At the order level, the composition and distribution of intestinal flora in each group of mice were predominantly characterized by Clostridia and Bacteroidetes (Figure 8C). The model group displayed a reduced abundance of Bacteroides and an increased abundance of Clostridia compared with the blank group. Aside from the TDDH group, the remaining experimental groups demonstrated similar trends; however, the Bacteroidetes and Clostridia levels in the TDDH group were comparable to those of the blank group. At the family level, the distribution structure of intestinal flora in mice across each group indicated dominance by Lachnospiraceae and Muribaculaceae (Figure 8D). The model group had decreased populations of Muribaculaceae and Ruminococcaceae but elevated populations of Spiralaceae and Lactobacillaceae. Notably, Ruminococcaceae play a critical role in degrading resistant starch, with the XZW group exhibiting the most significant recovery in this aspect. The intestinal flora structure distribution at the level of each group of mice (Figure 8E) primarily featured Lachnospiraceae as the predominant bacterial group. In comparison to the blank group, the model group displayed an improved population of Lachnospiraceae NK4A136 group species and a decrease in uncultured Bacteroidales bacterial species. However, following drug intervention, the TDDH group’s microbiota recovered, with Lactobacillus levels surpassing those of the blank group. At the species level, the distribution of intestinal flora in each group of mice (Figure 8F) revealed that uncultured bacterial species did not significantly differ in abundance between the model and blank groups. Nevertheless, after drug intervention, there was an increase in the abundance of uncultured Bacteroidales bacterial kinds. There is a close relationship between the intestinal flora and breast hyperplasia. Breast hyperplasia may disrupt the balance of the intestinal flora, leading to a decrease in beneficial bacteria and an increase in harmful bacteria. The Compound Herba Gueldenstaedtiae and its fermentation products can regulate the structure of the intestinal flora and increase the abundance and diversity of beneficial bacteria. For example, the high-dose Compound Herba Gueldenstaedtiae restores the level of Bacteroidetes and reduces the level of Firmicutes. This may be achieved by regulating the intestinal internal environment, inhibiting the growth of harmful bacteria, and promoting the reproduction of beneficial bacteria, thus improving the intestinal microecology. The changes in the intestinal flora may in turn affect the health of the mammary gland tissue through the gut-mammary axis. Beneficial bacteria and their metabolites may regulate the body’s immune function and hormone levels, indirectly inhibiting breast hyperplasia. Effect of Compound Herba Gueldenstaedtiae on intestinal short-chain fatty acids in mice with breast hyperplasia The analysis of the effects of various drug interventions on intestinal SCFAs in each mouse group, as depicted in Figure 9, revealed several notable findings. Compared with the blank group, the model group demonstrated an evident decrease in acetic acid content, indicating a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05). This suggests that mammary gland hyperplasia in mice impacts acetic acid levels. Conversely, the TDDZ group displayed a substantial increase in acetic acid content relative to the model group, also indicating a statistical distinction (P < 0.001). Furthermore, both TDDD and TDDH groups demonstrated markedly higher acetic acid levels compared with the model group (P < 0.0001), as illustrated in Figure 9A. Propionic acid levels in the model group were notably lower than in the blank"

group, indicating a statistically significant difference (P < 0.001). However, when comparing the model group and the TDDD group, an increase in propionic acid content was observed, with a significant statistical difference (P < 0.05), as shown in Figure 9B. Regarding butyric acid, the TDDZ, TDDH, WSWD, and WSWH groups exhibited considerable variations in butyric acid content, which were statistically significant (P < 0.0001), as seen in Figure 9C. This suggests that the compound could enhance butyric acid levels in mice following water decoction and microbial probiotic fermentation. The levels of isobutyric acid remained unchanged between the model group and the blank group, suggesting that the isobutyric acid levels in mice were not affected by the modeling process. When comparing the model group to the other groups, no significant changes were observed, indicating that the compound had no effect on isobutyric acid in mice, as depicted in Figure 9D. Valeric acid levels in the model group were significantly reduced compared with the blank group (P < 0.001). However, there was no significant difference in valeric acid content (P > 0.05), suggesting that the compound’s water decoction treatment did not affect valeric acid levels in mice. Nevertheless, when compared with the model group, the WSWD, WSWZ, and WSWH groups showed increased valeric acid content, with statistical differences, as seen in Figure 9E. This indicates that microbial probiotic fermentation could elevate valeric acid levels in mice. The blank group had evidently higher levels of isovaleric acid than the model group (P < 0.01). The XZW, TDDZ, TDDH, and WSWH groups did not exhibit significant changes in isovaleric acid content (P > 0.05). However, the TDDD and WSWD groups displayed improved isovaleric acid levels, as depicted in Figure 9F, suggesting that low doses of traditional Chinese medicine could significantly enhance isovaleric acid content. Lastly, caproic acid levels remained unaffected across all intervention groups, as shown in Figure 9G. This demonstrates that there is no significant difference in caproic acid content in the bodies of mice with breast hyperplasia after being treated with this compound medication. These findings indicate that different drugs exert varying effects on intestinal metabolites in mice, potentially related to alterations in the abundance of intestinal flora species. SCFAs are important metabolites of the intestinal flora and play a crucial role in maintaining intestinal health and regulating the body’s metabolism. Breast hyperplasia affects the metabolic function of the intestinal flora, leading to abnormal production of SCFAs. The Compound Herba Gueldenstaedtiae and its fermentation products regulate the intestinal flora, promote the growth and metabolism of beneficial bacteria, and increase the production of SCFAs. For example, acetic acid, propionic acid, and butyric acid can bind to free fatty acid receptors to regulate intestinal immunity, inhibit inflammatory responses, and also affect fat metabolism and energy balance, thereby improving breast hyperplasia. Changes in the levels of valeric acid and isovaleric acid may also be related to the regulation of the intestinal flora. They may be involved in certain physiological processes of the body and have an impact on the development of breast hyperplasia."

| [1] SUN S, ZHANG K, WANG Y, et al. Pharmacodynamic structure of deer antler base protein and its mammary gland hyperplasia inhibition mechanism by mediating Raf-1/MEK/ERK signaling pathway activation. Food Funct. 2023;14(7):3319-3331. [2] PING Y, GAO Q, LI C, et al. Construction of microneedle of atractylodes macrocephala Rhizoma aqueous extract and effect on mammary gland hyperplasia based on intestinal flora. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14: 1158318. [3] YAN Z, YUN-YUN L, ZHOU T, et al. The relationship between using estrogen and/or progesterone and the risk of mammary gland hyperplasia in women: a meta-analysis. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2022;38(7):543-547. [4] LIU Y, WU D, WANG K, et al. Dose-dependent effects of royal jelly on estrogen- and progesterone-induced mammary gland hyperplasia in rats. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2022;66 (5):e2100355. [5] HU X, GUO J, ZHAO C, et al. The gut microbiota contributes to the development of Staphylococcus aureus-induced mastitis in mice. ISME J. 2020;14(7):1897-1910. [6] HU X, HE Z, ZHAO C, et al. Gut/rumen-mammary gland axis in mastitis: gut/rumen microbiota-mediated “gastroenterogenic mastitis”. J Adv Res. 2024;55: 159-171. [7] HEATH H, MOGOL AN, SANTALIZ CASIANO A, et al. Targeting systemic and gut microbial metabolism in ER (+) breast cancer. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2024;35(4):321-330. [8] LIANG Y, ZENG W, HOU T, et al. Gut microbiome and reproductive endocrine diseases: a Mendelian randomization study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1164186. [9] XIONG Y, LU X, LI B, et al. Bacteroides fragilis transplantation reverses reproductive senescence by transporting extracellular vesicles through the gut-ovary axis. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2025;12(9):e2409740. [10] LI L, WANG R, ZHANG A, et al. Evidence on efficacy and safety of Chinese medicines combined western medicines treatment for breast cancer with endocrine therapy. Front Oncol. 2021;11:661925. [11] WANG X, ZHANG P, ZHANG X. Probiotics regulate gut microbiota: an effective method to improve immunity. Molecules. 2021;26(19):6076. [12] JIA Y, LIU X, JIA Q, et al. The anti-hyperplasia of mammary gland effect of protein extract HSS from Tegillarca granosa. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;85:1-6. [13] YOU Z, SUN J, XIE F, et al. Modulatory effect of fermented papaya extracts on mammary gland hyperplasia induced by estrogen and progestin in female rats. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:8235069. [14] PATIL V, RUTERBUSCH JJ, CHEN W, et al. Multiplicity of benign breast disease lesions and breast cancer risk in African American women. Front Oncol. 2024; 14:1410819. [15] SUNG H, FERLAY J, SIEGEL RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: globocan estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209-249. [16] KLASSEN CL, HINES SL, GHOSH K. Common benign breast concerns for the primary care physician. Cleve Clin J Med. 2019;86(1):57-65. [17] FRAKER JL, CLUNE CG, SAHNI SK, et al. Prevalence, impact, and diagnostic challenges of benign breast disease: a narrative review. Int J Womens Health. 2023;15:765-778. [18] PARIDA S, SHARMA D. The microbiome-estrogen connection and breast cancer risk. Cells. 2019;8(12):1642. [19] LABORDA-ILLANES A, SANCHEZ-ALCOHOLADO L, DOMINGUEZ-RECIO ME, et al. Breast and gut microbiota action mechanisms in breast cancer pathogenesis and treatment. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(9):2465. [20] LUO J, YANG J, PENG M, et al. Efficacy and safety of Chinese herbal medicine wuwei xiaodu drink for wound infection: a protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101(48):e32135. [21] WEI S, QIAN L, NIU M, et al. The modulatory properties of Li-Ru-Kang treatment on hyperplasia of mammary glands using an integrated approach. front pharmacol. 2018;9:651. [22] WANG Y, WEI S, GAO T, et al. Anti-inflammatory effect of a TCM formula Li-Ru-Kang in rats with hyperplasia of mammary gland and the underlying biological mechanisms. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:1318. [23] SUN L, GUO D, LIU Q, et al. Efficacy of Lubeikangru formulation in mice with hyperplasia of the mammary glands induced by estrogen and progesterone. J Tradit Chin Med. 2019;39(2):174-180. [24] SUN L, GUO DH, LIU F, et al. A mouse model of mammary hyperplasia induced by oral hormone administration. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2017; 14(4):247-252. [25] SANCHEZ AM, FLAMINI MI, ZULLINO S, et al. Regulatory actions of LH and follicle-stimulating hormone on breast cancer cells and mammary tumors in rats. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2018;9:239. [26] KOŁODZIEJSKA R, TAFELSKA-KACZMAREK A, PAWLUK M, et al. Ashwagandha-induced programmed cell death in the treatment of breast cancer. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2024;46(7):7668-7685. [27] LIN W, GU C, CHEN Z, et al. Exploring the relationship between gut microbiota and breast cancer risk in European and East Asian populations using Mendelian randomization. BMC Cancer. 2024;24 (1):970. [28] SOTO-MARTIN EC, WARNKE I, FARQUHARSON FM, et al. Vitamin biosynthesis by human gut butyrate-producing bacteria and cross-feeding in synthetic microbial communities. mBio. 2020;11(4):e00886-20. [29] BARRETO HC, ABREU B, GORDO I. Fluctuating selection on bacterial iron regulation in the mammalian gut. Curr Biol. 2022;32(15):3261-3275.e4. [30] ZHANG L, ZHANG Z, XU L, et al. Maintaining the balance of intestinal flora through the diet: effective prevention of illness. Foods. 2021;10(10):2312. [31] WANG QR, SHAO J. Chinese medicinal formulae treat inflammatory bowel diseases through maintaining gut flora homeostasis. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2022;47(22):5997-6004. [32] NING Y, XU F, XIN R, et al. Palmatine regulates bile acid cycle metabolism and maintains intestinal flora balance to maintain stable intestinal barrier. Life Sci. 2020;262:118405. [33] ZHAO C, HU X, QIU M, et al. Sialic acid exacerbates gut dysbiosis-associated mastitis through the microbiota-gut-mammary axis by fueling gut microbiota disruption. Microbiome. 2023;11(1):78. [34] LI Y, LIU M, KONG B, et al. The role of selenium intervention in gut microbiota homeostasis and gene function in mice with breast cancer on a high-fat diet. Front Microbiol. 2024;15:1439652. [35] XUE M, JI X, LIANG H, et al. The effect of fucoidan on intestinal flora and intestinal barrier function in rats with breast cancer. Food Funct. 2018;9(2):1214-1223. [36] ZHANG D, JIAN YP, ZHANG YN, et al. Short-chain fatty acids in diseases. Cell Commun Signal. 2023;21(1):212. [37] FUSCO W, LORENZO MB, CINTONI M, et al. Short-chain fatty-acid-producing bacteria: key components of the human gut microbiota. Nutrients. 2023;15(9):2211. [38] KIM CH. Complex regulatory effects of gut microbial short-chain fatty acids on immune tolerance and autoimmunity. Cell Mol Immunol. 2023;20(4):341-350. [39] MURADÁS TC, FREITAS RD, GONÇALVES JI, et al. Potential antitumor effects of short-chain fatty acids in breast cancer models. Am J Cancer Res. 2024;14(5): 1999-2019. |

| [1] | Chen Yulin, He Yingying, Hu Kai, Chen Zhifan, Nie Sha Meng Yanhui, Li Runzhen, Zhang Xiaoduo , Li Yuxi, Tang Yaoping. Effect and mechanism of exosome-like vesicles derived from Trichosanthes kirilowii Maxim. in preventing and treating atherosclerosis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(7): 1768-1781. |

| [2] | Zhou Sirui, Xu Yukun, Zhao Kewei. Ideas and methods of anti-melanogenesis of Angelica dahurica extracellular vesicles [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(7): 1747-1754. |

| [3] | Peng Zhiwei, Chen Lei, Tong Lei. Luteolin promotes wound healing in diabetic mice: roles and mechanisms [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(6): 1398-1406. |

| [4] | Gu Fucheng, Yang Meixin, Wu Weixin, Cai Weijun, Qin Yangyi, Sun Mingyi, Sun Jian, Geng Qiudong, Li Nan. Effects of Guilu Erxian Glue on gut microbiota in rats with knee osteoarthritis: machine learning and 16S rDNA analysis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(4): 1058-1072. |

| [5] | Chen Yixian, Chen Chen, Lu Liheng, Tang Jinpeng, Yu Xiaowei. Triptolide in the treatment of osteoarthritis: network pharmacology analysis and animal model validation [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(4): 805-815. |

| [6] | Chai Jinlian, Liang Xuezhen, Sun Tiefeng, Li Shudong, Li Wei, Li Guangzheng, Yu Huayun, Wang Ping. Mechanistic insights into how Cervi Cornus Colla regulates the intestinal flora-bile acid metabolic pathway to alleviate steroid-induced osteonecrosis of the femoral head in a rat model [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(18): 4568-4581. |

| [7] | Yang Ling, Dai Jiahui, Zhou Han, Yang Lin, Bian Bogao, Liu Gang. Moderate-intensity exercise improves renal injury and inflammatory response in mice with hyperuricemia [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(18): 4638-4648. |

| [8] | Wu Xue, Zhang Linao, Luo Shifang, Liu Feifan, Wan Yan, Bai Yuanmei, Cao Julin, Xie Yuhuan, Guo Peixin. Dandeng Tongnao soft capsules against ischemic stroke: fingerprinting and network pharmacological analysis of efficacy and mechanism of action [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(17): 4517-4528. |

| [9] | Zhao Yu, Xue Yun, Huang Jiajun, Wu Diyou, Yang Bin, Huang Junqing. Total flavonoids from Semen Cuscutae inhibits osteoblast apoptosis in hormone-induced femoral head avascular necrosis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(17): 4289-4298. |

| [10] | Fu Xiao, Li Jigao, Yan Xiaonan, Song Zhe, Guo Yuejun, Li Hanbing, Zhou Quan. Traditional Chinese medicine effective ingredients for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: mechanism based on nuclear factor kappaB signaling pathway [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(16): 4180-4192. |

| [11] | Zou Yuxiong, Liu Xiaomeng, Liu Ying, Zhu Yue, Li Shuming, Guo Fangyang, Yu Xinyu, Nie Heyun, Liu Qian, Ao Meiying. Cerebral palsy decoction improves cerebral palsy in male and female young rats: mechanisms based on the “gut-brain-muscle” axis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(16): 4054-4066. |

| [12] | Zhou Wu, Zhang Jingxin, Liu Yuancheng, Hu Chenglong, Wang Siqi, Xu Jianxia, Huang Hai, Wei Sixi. Treatment of acute myeloid leukemia with corynoline: network pharmacology analysis of potential mechanisms and experimental validation [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(16): 4088-4104. |

| [13] | Huang Lei, Wang Xianghong, Zhang Xianxu, Li Shicheng, Luo Zhiqiang. Mechanism and therapeutic potential of nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 in regulating non-infectious spinal diseases [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(15): 3971-3982. |

| [14] | Sun Long, Wu Haiyang, Tong Linjian, Liu Rui, Yang Weiguang, Xiao Jian, Liu Lice, Sun Zhiming. Regulatory mechanism of leptin in bone metabolism [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(12): 3100-3108. |

| [15] | Wang Tao, Min Youjiang, Wang Min, Wang Shunpu, Li Le, Zhang Chen, Xiao Weiping, Yu Yiping. Causal relationship between gut microbiota and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: sample analysis from the IEU Open GWAS Database [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(12): 3182-3189. |

| Viewed | ||||||

|

Full text |

|

|||||

|

Abstract |

|

|||||