Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research ›› 2018, Vol. 22 ›› Issue (11): 1792-1797.doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-4344.0181

Previous Articles Next Articles

Heterotopic ossification after artificial disc replacement: problems and prospects

Zhao Bin-xiu1, Sun Yu2

- 1Department of Orthopedics, Affiliated Hospital of Guilin Medical University, Guilin 541001, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China; 2Department of Orthopedics, Third Hospital, Peking University, Beijing 100191, China

-

Online:2018-04-18Published:2018-04-18 -

About author:Zhao Bin-xiu, M.D., Associate chief physician, Department of Orthopedics, Affiliated Hospital of Guilin Medical University, Guilin 541001, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China

CLC Number:

Cite this article

Zhao Bin-xiu, Sun Yu. Heterotopic ossification after artificial disc replacement: problems and prospects[J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2018, 22(11): 1792-1797.

share this article

2.1 关于人工颈椎间盘的发展与异位骨化的评价 1962年瑞典人Fernstrom首开人工颈椎间盘置换术之先河,试图以金属球面体恢复椎间关节的运动轨迹。人工椎间盘在20世纪50年代始被研制,1950年,Nachemson以自凝硅胶注入尸体椎间盘尝试生物力学研究。1973年,Stubstad等研发了几种形状的弹性聚合物制作的椎间盘,并进行了初步研究。1991年Bao与Higham甚至发明了涤纶和尼龙等半透膜包裹的水凝胶珠作为人工椎间盘假体[8]。1998年Gill及其同事就Cummins设计的Bristol型颈人工椎间盘假体申请了专利,这种假体于1989年在英国的Frenchay医院的机械工程部被研发出来。第2代Bristol颈人工椎间盘假体采用金属对金属的不锈钢球窝设计,这就是Bristol/Cummins型人工椎间盘,也成为Prestige Ⅰ型假体。Prestige Ⅱ型假体是在前代假体的基础上改进而成,特点是具备低切迹、易于骨长入的表面以及有多种尺寸可供选择。之后,2002年出现了Prestige ST型假体,2003年出现了Prestige STLP型假体,2004年出现了Prestige LP型假体。目前,还有Bryan型、PCM(porous coated motion)型以及ProDisc-C人工椎间盘假体较为常见,见图1,此外还有NeoDisc,Cervicore(Stryker, Kalamazoo, MI)和Discovery(Scientix,Maitland, FL)等数种人工椎间盘种类假体出现并被应用,相信将来会有更多理想的假体出现。 人工椎间盘置换术保留手术节段的活动度以及恢复颈椎整体的曲度成为可能,而颈椎置换节段的活动度是评价颈椎人工间盘置换手术效果的重要指标之一。但是,颈椎人工椎间盘置换术后,常发生异位骨化,异位骨化使手术节段的活动性丧失,颈椎整体正常生理曲度丧失而变得僵直,这就改变了颈椎载荷的应力分布,容易导致邻椎病的发生。异位骨化是颈椎人工椎间盘置换后手术节段活动度下降及术后神经功能恢复不佳的重要影响因素[9]。"

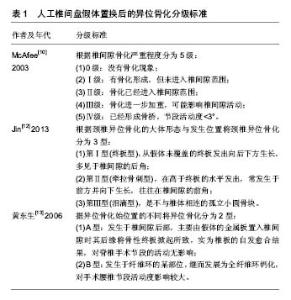

目前,国内外普遍采用McAfee[10]2003年制定的异位骨化分级方法。McAfee等[10]观察了接受人工椎间盘假体置换术的84例患者和17只大猩猩,并参照Brooker等[11]对于全髋关节置换术后异位骨化的分级方法制定了人工椎间盘假体置换术后的异位骨化分级标准。根据椎间隙骨化严重程度分为5级:①0级:没有骨化现象;②Ⅰ级:有骨化形成,但未进入椎间隙范围;③Ⅱ级:骨化已经进入椎间隙范围;④Ⅲ级:骨化进一步加重,可能影响椎间隙活动;⑤Ⅳ级:已经形成骨桥,节段活动度<3°。 韩国的Jin等[12]根据颈椎异位骨化的大体形态与发生位置将颈椎异位骨化分为3型:第Ⅰ型(终板型),从假体未覆盖的终板发出向后下方生长,多见于椎间隙的后角;第Ⅱ型(牵拉骨刺型),在高于终板的水平发出,常发生于前方并向下生长,往往在椎间隙的前角;第Ⅲ型(泪滴型),是不与椎体相连的孤立小圆骨块。 国内的黄东生等[13]根据异位骨化始位置的不同,将异位骨化分为2型。A型:发生于椎间隙后部,主要由假体的金属板置入椎间隙时其后缘将骨性终板掀起所致,实为椎板的的自发愈合结果,对脊椎手术节段的活动无影响;B型:发生于纤维环的某部位,继而发展为全纤维环钙化,对手术腰椎节段活动度影响较大。 使用Bryan假体植入患者中的异位骨化现象Gaffin[14]于2002年首先发现并在当年的佛罗里达举办的颈椎外科年会上予以率先报道,应用不同类型假体的颈椎人工椎间盘置换后二至三年异位骨化发病率为2%-79%[15-17];而国内的孙宇等[18]对接受Bryan人工颈椎间盘假体的患者随访5年,异位骨化发生率在30个手术节段中为12例,即40%,而其中McAfee Ⅳ级有3例,即10%丧失了节段活动度。 2.2 人工椎间盘置换后异位骨化的转归 Walraevens 等[19]随访接受Bryan假体的患者,4年时异位骨化发生率为34%,其中Ⅳ级异位骨化为5%;而6年时异位骨化发生率为38%,其中Ⅳ级异位骨化为8%;8年时异位骨化发生率为39%,其中Ⅳ级异位骨化仍为8%。更为重要的是,术后的临床效果与异位骨化的发生与否及级别无统计学相关性。Ⅳ级异位骨化的患者即使失败,可以看作是得到了前路颈椎间盘切除椎间植骨融合内固定的临床效果,比较安全。此中期随访结论为人工椎间盘置换是有效且比较安全的。国内黄东生等[13]随访65例78椎间隙接受SB Charite型人工椎间盘假体的颈椎患者,发现Ⅰ级异位骨化平均发生于术后2.5年,并于此后2.5年发展为Ⅱ-Ⅲ级,2例术前有间盘纤维钙化的患者术后6年发展为McAfee Ⅳ级。 因为人工椎间盘置换术开展时间并不长,术后患者的临床随访目前并无长期结果,以上数据仅说明其术后早中期临床转归结果良好,较差的结果亦可与前路颈椎间盘切除椎间植骨融合内固定相当,多数文献观察结果认为异位骨化多开始出现在术后12个月左右。 关于颈椎人工椎间盘置换后增加的颈椎节段活动角度,国内的数位学者对于颈椎人工椎间盘置换术后的短中期随访后认为手术节段的活动角度令人满意[18,20-21],显示了术后近期良好的临床效果。 2.3 异位骨化的易患因素 Leung等[22]认为颈椎人工椎间盘置换术后异位骨化的发生与颈椎活动度丢失之间关系密切,并进而指出男性、高龄与多节段置换被认为是人工椎间盘置换术后异位骨化的高危因素,而骨碎渣、金属磨削碎屑、ProDisc-C假体的嵴状结构以及假体与终板之间的应力也被认为与异位骨化的发生有关系。Gaffin认为异位骨化的发生原因在于手术创伤,若不加抗炎药物干涉,使用Bryan假体植入的患者的异位骨化发生率为17%,并且认为Bryan假体比其他几种使用金属材料较少的假体更易于发生异位骨化。有研究者推测诱发异位骨化出现的原因是对椎体终板的损伤而不是对肌肉的损伤[23]。因此有人提出理想的手术操作时对肌肉轻柔牵拉而对椎体终板无损伤。Yang等[24]认为导致术后异位骨化的因素是术前严重的骨关节炎和/或颈椎后纵韧带骨化症,故他认为治疗有局部骨化的颈椎病应以椎间植骨融合为宜,以阻断非正常骨化进程。也有学者认为围手术期的非类固醇抗炎药物应用、手术中对颈长肌的刺激以及钻磨骨质后遗留的骨碎渣都属于臆想因素,而没有统计相关性[25]。 周非非等[26]认为术前病变节段椎间隙高度、术后手术节段活动度与术后异位骨化形成有关,术前节段椎间隙高度丢失>20%者不适合接受Bryan人工椎间盘置换术。 Lee等[27]随访了48例行单节段颈椎人工椎间盘置换手术的患者达平均14个月,观察到异位骨化的发生时间术后11个月,异位骨化的发生率为13/48,而McAfee3级以上的异位骨化很少(1例),且异位骨化的发生未影响良好的术后临床效果及颈椎生物力学活动(ROM)。认为年龄、性别、围手术期非类固醇抗炎药的应用对于人工椎间盘置换术后异位骨化的发生无统计学意义上的影响。 Yi等[25]随访170例颈椎全髋关节置换患者达平均19.9个月,术后异位骨化的发生率为40.6%,分析在几个异位骨化的假定诱发因素中,只有男性(男女性的异位骨化发生率分别为47.6%,29.2%)、人工椎间盘假体的形状对异位骨化的发生具有统计学意义上的影响,男女性患异位骨化的机会比为2.117,Mobi-C(LDR medical,Troyes,France)、ProDisc-C(Synthes,Inc,West,Chester,PA,USA)与Bryan型假体术后发生异位骨化的机会比分别是5.262与7.449。而术前的颈椎退变(包括椎体前后方的骨赘、前后纵韧带钙化与项韧带钙化)对异位骨化的发生率不具有统计学意义上的相关性,虽然具备这些因素似乎有加重患者术后异位骨化的倾向,并且术后的异位骨化的分级与预测的危险因素无统计相关性。 Vandenput等[28]认为性别对异位骨化的影响可归结为性激素的作用效果,称雌激素对成年男性骨密度、骨转化与骨量丢失的影响较睾酮更为重大。而对于单节段前路颈椎间盘切除椎间植骨融合内固定,有研究认为高龄及女性是术后相邻节段骨化的危险因素[29],这可能与高龄颈椎自然退变及女性患者骨质退变相关,使用Zero-P,抗骨质疏松治疗,减少术中出血,选用合理长度的钛板和合适的摆放位置可降低术后相邻节段异位骨化的发生。但这些研究结果只是术后早期的随访结果,目前尚缺乏大样本的中远期随访研究[30]。 Jin等[31]认为异位骨化的形态分型与受到的机械应力有关系,第Ⅰ型系受到压应力形成,第Ⅱ型系受到拉力形成。他们研究了接受Bryan、PCM及Prestige LP三种类型假体的患者各30例,发现在接受PCM假体的患者中异位骨化发生率高于接受另外两种假体的患者术后异位骨化的发生率,归因于使用PCM假体时椎体骨髓被更多地暴露,故得出异位骨化与椎间盘假体形状有关的结论。 2.4 关于异位骨化发生的机制 至今,对于异位骨化的发生机制研究尚未完全明析,目前大多数研究认为炎症因子在特殊微环境下诱导成骨的理论占据主导地位,其诱导成纤维细胞软骨内成骨,而使异位骨化形成。一般认为,异位骨化与正常骨形成机制存在差异学者,异位骨化发生需具备3个条件:骨生成诱导因子、前体细胞和局部微环境,在一系列细胞和信号分子的参与下异位骨化才会形成[32-33]。发生于颈椎人工椎间盘置换术后的异位骨化不同于全髋关节置换与全膝关节置换术后的异位骨化,前者很少出现红肿热痛的一般炎性反应,更像融合术后的骨形态或者是退变性的骨赘。Liu等[34]经过10年的回顾性研究发现异位骨化较常存在于退变性与修复性疾患,而较少量发生于肿瘤病患,且免疫组化染色分析,异位骨化中骨形态发生蛋白1与骨形态发生蛋白4较常见,而骨形态发生蛋白6不常见。 在手术所致的软组织受损伤后导致的组织缺氧微环境下,目前确定有淋巴细胞、巨噬细胞等炎症细胞被兴奋化及趋化至受损的结缔组织周围,而激发受损组织内的内皮细胞,再经激活素受体样激酶ALK2骨形态发生蛋白1型受体信号转导通路分化为成纤维细胞从而释放骨生成诱导因子,促使成纤维细胞增殖分化为成骨前体细胞,进而促使异位骨形成[35]。 异位骨化发生的具体分子机制目前尚未完全明确,对于基因系谱的研究发现异位骨化发生极有可能与负责编码ACVR1(ALK2)的基因上的单核苷酸(R206H)的突变有关系,突变导致骨形态发生蛋白受体在没有配体的情况下可被激活[36]。有研究发现骨形态发生蛋白1型受体拮抗剂和激素也可有效阻止大鼠模型中异位骨化的发生,这提示炎症和骨形态发生蛋白介导的信号转导通路在异位骨化的形成中都可以起作用。有研究提示,在异位骨化形成过程中,较为重要的分子为Smad 4和Runx 2[37],而神经肽P物质在骨形态发生蛋白介导的异位骨化形成过程中可有效阻止异位骨化的发生过程[38]。 2.5 关于异位骨化的预防与治疗 目前临床上最常用的预防异位骨化发生的药物为非类固醇抗炎药,其作用机制是抑制介导炎症反应的前列腺素的产生。这类药物如阿司匹林、布洛芬和吲哚美辛等。由于其同时抑制了介导正常生理过程的前列腺素的产生,以及其较为常见的胃肠道溃疡、心血管不良事件等副作用,故选择性环氧化酶2抑制剂近年来应用较为广泛。而双膦酸盐预防异位骨化发生的作用机制是抑制骨化过程中磷酸钙转化成羟磷灰石,从而阻止骨基质钙化过程。需要说明的是非类固醇抗炎药物和双膦酸盐都只能预防异位骨化的发生,对于已发生的异位骨化几乎无治疗作用。 小剂量局部放射疗法是目前常用的除了药物以外的另外一种预防异位骨化发生的方法,其机制是抑制间充质干细胞颗粒化[39],但放射疗法可导致骨折延迟愈合或不愈合[40]。Pakos等[41]经过对关于非类固醇抗炎药物与放射治疗在防治髋关节手术后异位骨化的效果随机研究的荟萃分析后得出结论:放射治疗在防治异位骨化的效果在统计学上优于非类固醇抗炎药物。 林霖等[42]的研究认为,在动物模型,腺病毒介导的拮抗Runx2/Cbfa1的siRNA可以有效预防由骨形态发生蛋白4诱导的异位骨化形成。近年,低氧诱发因子1a信号通路对于血管内皮生长因子的研究较多。Zimmermann等[43]在关于小鼠后腿肌腱切断模型上的研究认为棘霉素(Echinomycin)对于此机制诱导的异位骨化有抑制作用,但同时指出,在其研究中棘霉素相比对照组仅仅减少异位骨化的形成量,而不能完全遏制异位骨化的形成。有研究发现对于大鼠异位骨化模型,骨形态发生蛋白抑制剂LDN-193189可以有效抑制异位骨化的形成[44]。治疗原发性异位骨化(即进行性纤维发育不良性骨化症)的异维甲酸(13-顺式维甲酸)可以减少人工颈椎间盘置换术后异位骨化的发生[45]。 对于已经产生神经压迫的异位骨化病灶,手术切除是必要而且有效的,但有一定的复发率,一般认为血液中碱性磷酸酶的水平稳定与否是决定手术时机的可靠因素。"

| [1] Yang S, Wu X, Hu Y, et al. Early and intermediate follow-up results after treatment of degenerative disc disease with the Bryan cervical disc prosthesis: single- and multiple-level. Spine. 2008;33:E371-E377.[2] Kibuule LK, Jeffrey S, Fischgrund JS. Complications of cervical disc arthroplasty. Semin Spine Surg. 2009;21: 185-193.[3] 刘浩,邓宇骁,刘子扬,等. Pretic-Ⅰ人工颈椎间盘置换术治疗颈椎间盘突出症的早期疗效观察[J].中国修复重建外科杂志,2017, (31)5:1-6.[4] Dong L, Tan MS, Yan QH, et al. Footprint mismatch of cervical disc prostheses with Chinese cervical anatomic dimensions. Chin Med J (Engl). 2015;128(2): 197-202.[5] 唐文. 颈椎间盘置换与颈前路椎间盘切除减压植骨融合治疗退变性颈椎病的Meta分析[D].南昌大学,2010.[6] 娄纪刚,刘浩,龚全,等. 单节段 Prestige LP 人工颈椎间盘置换术后置换节段活动度的影响因素分析[J]. 颈腰痛杂志, 2015, 36(1):20-24.[7] 徐帅,朱震奇,钱亚龙,等.颈椎人工椎间盘置换与椎间盘切除融合术后邻近节段退变比较研究的Meta 分析[J].中国脊柱脊髓杂志, 2017,27(4):296-304.[8] Porchet F, Metcalf NH. Clinical outcomes with the prestige II cervical disc: preliminary results from a prospective randomized clinical trial. Neurosurg Focus.2004;17:E6.[9] 梁英杰,张光明,温世峰,等. Discover人工颈椎间盘置换术后异位骨化的临床研究[J].中国临床解剖学杂志,2015,33(3): 336-340.[10] McAfee PC, Cunningham BW, Devine J,et al. Classification of Heterotopic Ossification (HO) in artificial disk replacement. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2003;16(4): 384-389.[11] Brooker AF, Bowerman JW, Robinson RA, et al. Ectopic ossification following total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1973;55:1629-1632.[12] Jin YJ, Park SB, Kim MJ, et al.An analysis of heterotopic ossification in cervical disc arthroplasty:a novel morphologic classification of an ossified mass. Spine J. 2013;13:408-420.[13] 黄东生,梁安靖,叶伟,等.人工腰椎间盘置换术后异位骨化的危险因素及其对策[J].中华外科杂志, 2006,44(4):242-245.[14] Goffin J. Complications of cervical disc arthroplasty. Semin Spine Surg. 2006;(18):87-98.[15] Yi S, Kim KN, Yang MS, et al. Difference in occurrence of heterotopic ossification according to prosthesis type in the cervical artificial disc replacement. Spine. 2010;35: 1556-1561.[16] Suchomel P, Jurak L, Benes V 3rd, et al. Clinical results and development of heterotopic ossification in total cervical disc replacement during a 4-year follow-up. Eur Spine J. 2010;19: 307-315.[17] Lee JH, Jung TG, Kim HS, et al. Analysis of the incidence and clinical effect of the heterotopic ossification in a single-level cervical artificial disc replacement. Spine J. 2010;10:676-682.[18] 孙宇,赵衍斌,周非非,等.Bryan颈椎人工椎间盘置换术后5年随访结果[J].中国脊柱脊髓杂志,2012,22(1):1-7.[19] Walraevens J, Demaerel P, Suetens P, et al: Longitudinal prospective long-term radiographic follow-up after treatment of single-level cervical disk disease with the Bryan Cervical Disc. Neurosurgery. 2010;67:679-687.[20] 赵耀,刘屹林,王利民,等.Activ C人工椎间盘置换术治疗颈椎病的早期疗效[J]. 中国脊柱脊髓杂志,2012,22(10):868-873.[21] 张雪松,张永刚,肖嵩华,等.节段人工椎间盘置换治疗颈椎病的中长期疗效[J]. 中国脊柱脊髓杂志,2012,22(10):879-884.[22] Leung C, Casey AT, Goffin J, et al. Clinical significance of heterotopic ossification in cervical disc replacement:a prospective multicenter clinical trial. Neurosurgery. 2005;57: 759-763.[23] Kerr EJ, Jawahar A, Kay S,et al. Implant design may influence delayed heterotopic ossification after total disk arthroplasty in lumbar spine. Surg Neurol.2009; 72:747-751.[24] Yang S,Wu X,Hu Y,et al. Early and intermediate follow-up results after treatment of degenerative disc disease with the Bryan cervical disc prosthesis: single- and multiple-level. Spine. 2008;33:E371-E377.[25] Yi S, Shin DA, Kim KN, et al.The predisposing factors for the heterotopic ossification after cervical artificial disc replacement. J Spine. 2013;13(9):1048-1054.[26] 周非非,赵衍斌,孙宇,等.Bryan人工颈椎间盘置换术后异位骨化形成的临床因素分析[J].中国脊柱脊髓杂志,2009,19(1):39-43.[27] Lee JH, Jung TG, Kim HS, et al. Analysis of the incidence and clinical effect of the heterotopic ossification in a single-level cervical artificial disc replacement. J Spine. 2010;10 :676-682.[28] Vandenput L, Ohlsson C. Sex steroid metabolism in the regulation of bone health in men. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2010;121:582-588.[29] 陈昆,刘爱刚,蔡惠民. 颈前路减压融合术后相邻节段异位骨化的危险因素分析[J].实用骨科杂志,2017, 23(3):198-202.[30] 周波,贺西京.Zero-P治疗单节段脊髓型颈椎病的临床疗效分析[J]. 实用骨科杂志,2016,22(9):769-773..[31] Jin YJ, Park SB, Kim MJ, et al. An analysis of heterotopic ossification in cervical disc arthroplasty:a novel morphologic classification of an ossified mass. Spine J.2013;13: 408–420.[32] Peterson JR, de la Rosa S, Sun HL, et al. Burn injury enhances bone formation in heterotopic ossification model. Ann Surg. 2014;259(5):993-998.[33] Gurkan UA,Golden R,Kishore V,et al.Immune and inflammatory pathway are involved in inherenr bone marrow ossification.Clin Orthop Relate Res. 2012;470(9):2528-2540.[34] Liu K, Tripp S, Layfield LJ. Heterotopic ossification: Review of histologic findings and tissue distribution in a 10-year experience. Pathology. 2007;203:633-640.[35] Wosczyn MN, Biswas AA,Cogswell CA,et al.Multipotent progenitors resident in the skeletal muscle interstitium exhibit Mrobust BMP-dependent osteogenic activity and mediate heterotopic ossification.J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27(5): 1004-1017.[36] Culbert AL,Chakkalakal SA,Theosmy EG,et al.Alk2 regulates early chondrogenic fate in fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva heterotopic endochondral ossification. Stem Cells. 2014;32(5):1289-1300.[37] Heuriquez B,Hepp M,Merino P,et al.C/EBP B binds the P1 promoter of the Runx2 gene and up-regulates Runx2 transcription in osteoblastic cells.J Cell Physiol. 2011;226(11): 3043-3052.[38] Salisbury E,Rodenberg E,Sonnet C,et al.Sensory nerve induced inflammation contributes to heterotopic ossification.J Cell Biochem. 2011;112(10):2748-2758.[39] Mazonakis M,Berris T,Lyraraki E,et al.Cancer risk estimates from radiation therapy for heterotopic ossification prophylaxis after total hip arthroplasty.Med Phys. 2013;40(10):101702.[40] Hoff P,Rakow A,Gaber T,et al.Preoperative irradiation for the prevention of heterotopic ossification induces local inflammation in humans.Bone. 2013;55(1):93-101.[41] Pakos EE, Ioannidis JP. Radiotherapy vs. nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the prevention of heterotopic ossification after major hip procedures: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;60(3): 888-895.[42] Lin L, Chen L, Wang H, et al. Adenovirus-mediated transfer of siRNA against Runx2/Cbfa1 inhibits the formation of heterotopic ossification in animal model. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;349(2):564-572. [43] Zimmermann SM, Wurgler-Hauri CC, Wanner GA, et al. Echinomycin in the prevention of heterotopic ossification - An experimental antibiotic agent shows promising results in a murine model. Injury. 2013;44:570-575.[44] Yu PB, Deng DY, Lai CS, et al. BMP type I receptor inhibition reduces heterotopic ossification. Nat Med. 2008;14(12): 1363-1369.[45] Kaplan FS, Shore E. Derailing heterotopic ossification and RNRing to go. Nat Med. 2011;17(4):420-421. |

| [1] | Zhang Tongtong, Wang Zhonghua, Wen Jie, Song Yuxin, Liu Lin. Application of three-dimensional printing model in surgical resection and reconstruction of cervical tumor [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(9): 1335-1339. |

| [2] | Zeng Yanhua, Hao Yanlei. In vitro culture and purification of Schwann cells: a systematic review [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 1135-1141. |

| [3] | Xu Dongzi, Zhang Ting, Ouyang Zhaolian. The global competitive situation of cardiac tissue engineering based on patent analysis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(5): 807-812. |

| [4] | Wu Zijian, Hu Zhaoduan, Xie Youqiong, Wang Feng, Li Jia, Li Bocun, Cai Guowei, Peng Rui. Three-dimensional printing technology and bone tissue engineering research: literature metrology and visual analysis of research hotspots [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(4): 564-569. |

| [5] | Chang Wenliao, Zhao Jie, Sun Xiaoliang, Wang Kun, Wu Guofeng, Zhou Jian, Li Shuxiang, Sun Han. Material selection, theoretical design and biomimetic function of artificial periosteum [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(4): 600-606. |

| [6] | Liu Fei, Cui Yutao, Liu He. Advantages and problems of local antibiotic delivery system in the treatment of osteomyelitis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(4): 614-620. |

| [7] | Li Xiaozhuang, Duan Hao, Wang Weizhou, Tang Zhihong, Wang Yanghao, He Fei. Application of bone tissue engineering materials in the treatment of bone defect diseases in vivo [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(4): 626-631. |

| [8] | Zhang Zhenkun, Li Zhe, Li Ya, Wang Yingying, Wang Yaping, Zhou Xinkui, Ma Shanshan, Guan Fangxia. Application of alginate based hydrogels/dressings in wound healing: sustained, dynamic and sequential release [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(4): 638-643. |

| [9] | Chen Jiana, Qiu Yanling, Nie Minhai, Liu Xuqian. Tissue engineering scaffolds in repairing oral and maxillofacial soft tissue defects [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(4): 644-650. |

| [10] | Xing Hao, Zhang Yonghong, Wang Dong. Advantages and disadvantages of repairing large-segment bone defect [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(3): 426-430. |

| [11] | Chen Siqi, Xian Debin, Xu Rongsheng, Qin Zhongjie, Zhang Lei, Xia Delin. Effects of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and human umbilical vein endothelial cells combined with hydroxyapatite-tricalcium phosphate scaffolds on early angiogenesis in skull defect repair in rats [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(22): 3458-3465. |

| [12] | Wang Hao, Chen Mingxue, Li Junkang, Luo Xujiang, Peng Liqing, Li Huo, Huang Bo, Tian Guangzhao, Liu Shuyun, Sui Xiang, Huang Jingxiang, Guo Quanyi, Lu Xiaobo. Decellularized porcine skin matrix for tissue-engineered meniscus scaffold [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(22): 3473-3478. |

| [13] | Mo Jianling, He Shaoru, Feng Bowen, Jian Minqiao, Zhang Xiaohui, Liu Caisheng, Liang Yijing, Liu Yumei, Chen Liang, Zhou Haiyu, Liu Yanhui. Forming prevascularized cell sheets and the expression of angiogenesis-related factors [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(22): 3479-3486. |

| [14] | Liu Chang, Li Datong, Liu Yuan, Kong Lingbo, Guo Rui, Yang Lixue, Hao Dingjun, He Baorong. Poor efficacy after vertebral augmentation surgery of acute symptomatic thoracolumbar osteoporotic compression fracture: relationship with bone cement, bone mineral density, and adjacent fractures [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(22): 3510-3516. |

| [15] | Liu Liyong, Zhou Lei. Research and development status and development trend of hydrogel in tissue engineering based on patent information [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(22): 3527-3533. |

| Viewed | ||||||

|

Full text |

|

|||||

|

Abstract |

|

|||||