Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research ›› 2019, Vol. 23 ›› Issue (25): 3944-3950.doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-4344.1782

Previous Articles Next Articles

Human glioma-initiating cells stably transfected with red fluorescent protein gene can spontaneously fuse with host-derived bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and induce malignant transformation

Han Hui1, Dai Xingliang2, Cheng Hongwei2, Lan Qing1

- 1Department of Neurosurgery, the Second Af?liated Hospital of Soochow University, Suzhou 215004, Jiangsu Province, China; 2Department of Neurosurgery, the First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, Hefei 230022, Anhui Province, China

-

Revised:2019-03-19Online:2019-09-08Published:2019-09-08 -

Contact:Lan Qing, Professor, Chief physician, Doctoral supervisor, Department of Neurosurgery, the Second Af?liated Hospital of Soochow University, Suzhou 215004, Jiangsu Province, China -

About author:Han Hui, Department of Neurosurgery, the Second Af?liated Hospital of Soochow University, Suzhou 215004, Jiangsu Province, China -

Supported by:the National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 81702457 (to DXL); Suzhou Science and Technology Project, No. SYS201723 (to DXL)

CLC Number:

Cite this article

Han Hui, Dai Xingliang, Cheng Hongwei, Lan Qing. Human glioma-initiating cells stably transfected with red fluorescent protein gene can spontaneously fuse with host-derived bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and induce malignant transformation[J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2019, 23(25): 3944-3950.

share this article

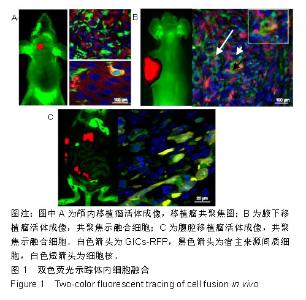

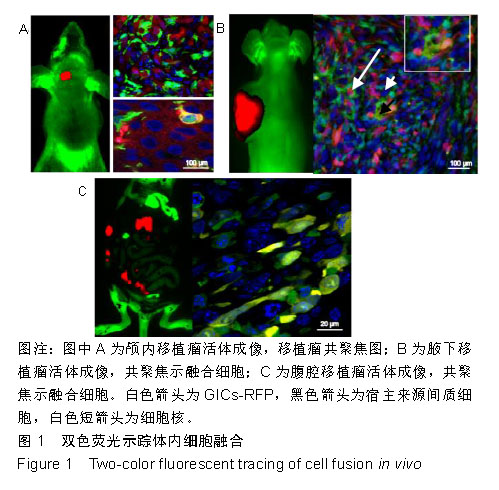

2.1 双色荧光示踪动物模型体内细胞的融合 GICs-RFP是作者所在实验室从人脑胶质母细胞瘤组织标本中原代培养并克隆到的一株具高侵袭的胶质瘤起始细胞[21],可稳定转染红色荧光蛋白基因载体后,经嘌呤霉素筛选和流式分选得到几乎100%表达红色荧光蛋白的GICs-RFP。实验小鼠为本实验室自建的全身表达绿色荧光蛋白的裸小鼠。多模式小动物活体成像仪下可以观察到GICs-RFP细胞移植到荧光裸小鼠颅内、皮下和腹腔后的致瘤效果,见图1,在激光扫描共聚焦显微镜下,可见大量绿色的宿主来源绿色荧光蛋白细胞浸润到表达红色荧光蛋白的实体肿瘤中,参与了肿瘤细胞间质的组成,并可见少数共表达绿色荧光蛋白和红色荧光蛋白的融合细胞,见图1。"

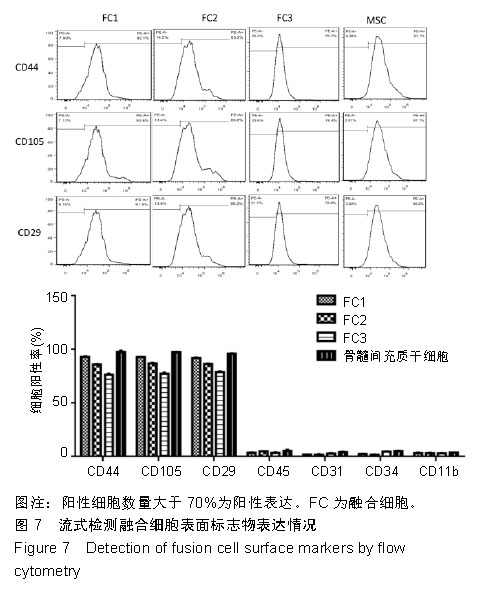

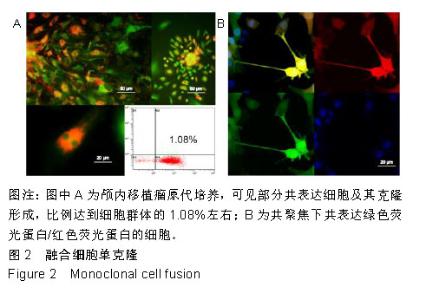

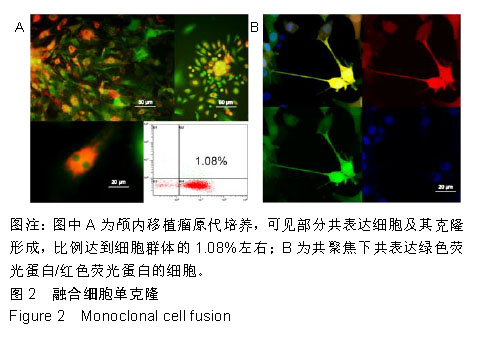

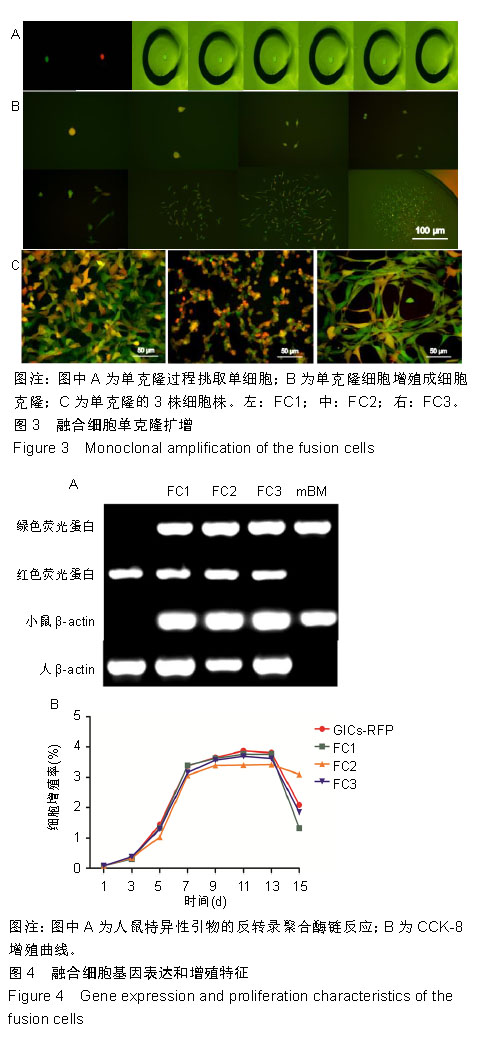

2.2 融合细胞的分离和单克隆 无菌条件下取颅内移植瘤肿瘤组织进行原代培养,2周左右后,在部分原代细胞集落中可见共表达绿色荧光蛋白和红色荧光蛋白的细胞克隆,部分细胞甚至为双细胞核细胞,流式细胞仪检测显示共表达细胞约占原代细胞群1.08%,见图2A。在激光扫描共聚焦显微镜下,这些细胞为既高表达红色荧光蛋白,又高表达绿色荧光蛋白的有核活细胞,称其为融合细胞(fusion cells,FCs),见图2B。利用自制毛细吸管显微镜下挑取单细胞做克隆,克隆后的细胞在显微镜下每天观察,确认是单个细胞分裂来源的克隆,见图3A,B。从颅内、腹腔和皮下移植瘤中克隆得到3个共表达绿色荧光蛋白/红色荧光蛋白的克隆细胞株,分别命名为FC1,FC2和FC3,3株细胞形态各异,颅内来源的FC1为多角形,腹腔来源的FC2为少突触的圆形,皮下来源的FC3为纤维型,见图3C。"

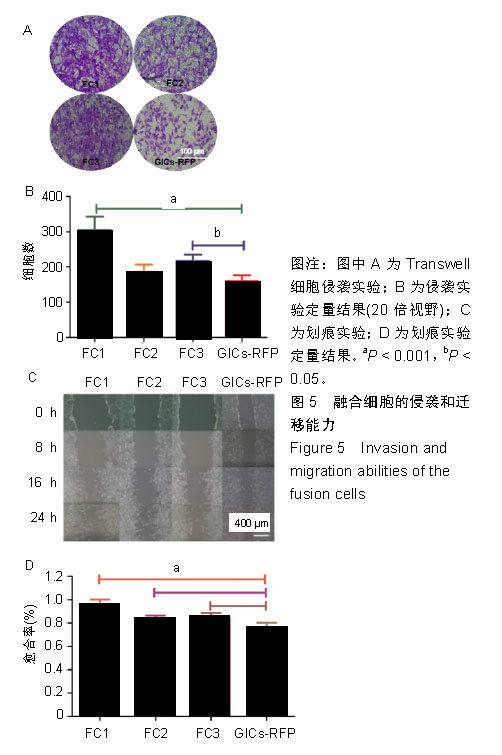

2.3 融合细胞的生物学特征 通过人鼠特异性引物行反转录聚合酶链反应检测,GICs-RFP为人源对照,绿色荧光蛋白裸小鼠骨髓冲洗细胞作为鼠源对照,3株融合细胞均共转录人鼠β-actin基因,证实融合细胞包含人源和鼠源基因组成分并转录,见图4A;结合荧光蛋白示踪的方法,来源于人GICs-RFP的红色荧光蛋白基因和来源于鼠的绿色荧光蛋白基因共同表达于融合细胞,证实了融合细胞不仅包含人源和鼠源基因成分,并且有明确的转录和表达。由此从基因组和蛋白水平证实FC1,FC2和FC3为人/鼠自发融合细胞。 2.4 融合细胞的细胞增殖能力 这三株细胞在体外均展示出无限增殖的永生化特征,CCK-8增殖曲线示3株融合细胞的增殖特征与GICs-RFP没有明显差异,见图4B。"

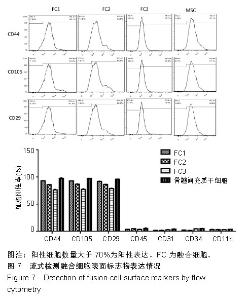

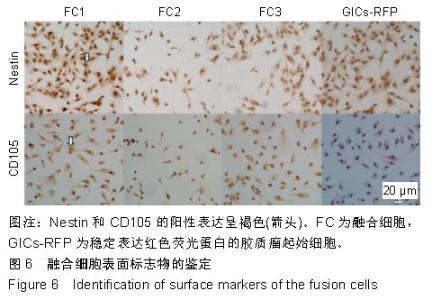

2.6 融合细胞表面标志物的鉴定 免疫细胞化学结果提示3株细胞均共表达胶质细胞标记物Nestin和CD105,见图6。流式细胞检测实验显示3株细胞高表达骨髓间充质干细胞标记物CD44、CD105和CD29,融合细胞FC1、FC2、FC3的阳性率分别为:CD44为92.1%、85.5%和76.1%,CD105为92.8%、86.6%和76.4%,CD29为91.9%、96.2%和78.9%;但不表达CD45、CD31、CD34和CD11b,融合细胞FC1、FC2、FC3的阳性率分别为:CD45为3.63%、4.99%和3.81%,CD31为1.55%、1.76%和2.03%,CD34为2.22、1.50%和4.22%,CD11b为3.00%、3.27%和2.99%,见图7,提示融合细胞来源于宿主骨髓间充质间质细胞。"

| [1]Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, et al. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131(6):803-820.[2]Lapointe S, Perry A, Butowski NA. Primary brain tumours in adults. Lancet. 2018;392(10145):432-446. [3]Lee JH, Lee JE, Kahng JY, et al. Human glioblastoma arises from subventricular zone cells with low-level driver mutations. Nature. 2018; 560(7717):243-247. [4]Wick W, Gorlia T, Bendszus M, et al. Lomustine and Bevacizumab in Progressive Glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(20):1954-1963.[5]Najafi M, Goradel NH, Farhood B, et al. Tumor microenvironment: Interactions and therapy. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(5):5700-5721. [6]Hoshino A, Costa-Silva B, Shen TL, et al. Tumour exosome integrins determine organotropic metastasis. Nature. 2015;527(7578):329-335. [7]Novikova MV, Khromova NV, Kopnin PB. Components of the Hepatocellular Carcinoma Microenvironment and Their Role in Tumor Progression. Biochemistry (Mosc). 2017;82(8):861-873.[8]Witz IP. The tumor microenvironment: the making of a paradigm. Cancer Microenviron. 2009;2 Suppl 1:9-17.[9]Yang M, Reynoso J, Jiang P, et al. Transgenic nude mouse with ubiquitous green fluorescent protein expression as a host for human tumors. Cancer Res. 2004;64(23):8651-8656.[10]Suetsugu A, Katz M, Fleming J, et al. Multi-color palette of fluorescent proteins for imaging the tumor microenvironment of orthotopic tumorgraft mouse models of clinical pancreatic cancer specimens. J Cell Biochem. 2012;113(7):2290-2295. [11]Wang A, Dai X, Cui B, et al. Experimental research of host macrophage canceration induced by glioma stem progenitor cells. Mol Med Rep. 2015;11(4):2435-2442. [12]Dai X, Chen H, Chen Y, et al. Malignant transformation of host stromal ?broblasts derived from the bone marrow traced in a dual-color fluorescence xenograft tumor model. Oncol Rep. 2015;34(6):2997-3006.[13]Shultz LD, Goodwin N, Ishikawa F, et al. Human cancer growth and therapy in immunodeficient mouse models. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2014;2014(7):694-708. [14]Lai Y, Wei X, Lin S, et al. Current status and perspectives of patient-derived xenograft models in cancer research. J Hematol Oncol. 2017;10(1):106. [15]Roque-Lima B, Roque CCTA, Begnami MD, et al. Development of patient-derived orthotopic xenografts from metastatic colorectal cancer in nude mice. J Drug Target. 2018. doi: 10.1080/1061186X. 2018.1509983. [Epub ahead of print][16]Ye D, Zhou C, Wang S, et al. Tumor suppression effect of targeting periostin with siRNA in a nude mouse model of human laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Lab Anal. 2019;33(1):e22622. [17]Jacobsen BM, Harrell JC, Jedlicka P, et al. Spontaneous fusion with, and transformation of mouse stroma by, malignant human breast cancer epithelium. Cancer Res. 2006;66(16):8274-8279.[18]Goldenberg DM, Zagzag D, Heselmeyer-Haddad KM, et al. Horizontal transmission and retention of malignancy, as well as functional human genes, after spontaneous fusion of human glioblastoma and hamster host cells in vivo. Int J Cancer. 2012;131(1):49-58. [19]Liu J, Zhang Y, Bai L, et al. Rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells undergo malignant transformation via indirect co-cultured with tumour cells. Cell Biochem Funct. 2012;30(8):650-656. [20]Chen Y, Wang Z, Dai X, et al. Glioma initiating cells contribute to malignant transformation of host glial cells during tumor tissue remodeling via PDGF signaling. Cancer Lett. 2015;365(2):174-181. [21]Wan Y, Fei XF, Wang ZM, et al. Expression of miR-125b in the new, highly invasive glioma stem cell and progenitor cell line SU3. Chin J Cancer. 2012;31(4):207-214.[22]Dong J, Dai XL, Lu ZH, et al. Incubation and application of transgenic green fluorescent nude mice in visualization studies on glioma tissue remodeling. Chin Med J (Engl). 2012;125(24):4349-4354.[23]Chen Z, Guo P, Xie X, et al. The role of tumour microenvironment: a new vision for cholangiocarcinoma. J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23(1):59-69. [24]Gentilini A, Pastore M, Marra F, et al. The Role of Stroma in Cholangiocarcinoma: The Intriguing Interplay between Fibroblastic Component, Immune Cell Subsets and Tumor Epithelium. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(10):E2885. [25]Weniger M, Honselmann KC, Liss AS. The Extracellular Matrix and Pancreatic Cancer: A Complex Relationship. Cancers (Basel). 2018; 10(9):E316.[26]Zhang X, Ding K, Wang J, et al. Chemoresistance caused by the microenvironment of glioblastoma and the corresponding solutions. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;109:39-46. [27]Agorku DJ, Tomiuk S, Klingner K, et al. Depletion of Mouse Cells from Human Tumor Xenografts Significantly Improves Downstream Analysis of Target Cells. J Vis Exp. 2016;(113). [28]Rycaj K, Li H, Zhou J, et al. Cellular determinants and microenvironmental regulation of prostate cancer metastasis. Semin Cancer Biol. 2017;44:83-97. [29]López-Soto A, Gonzalez S, Smyth MJ, et al. Control of Metastasis by NK Cells. Cancer Cell. 2017;32(2):135-154.[30]Chen K, Liu Q, Tsang LL, et al. Human MSCs promotes colorectal cancer epithelial-mesenchymal transition and progression via CCL5/β-catenin/Slug pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8(5):e2819. [31]Yu Y, Zhang Q, Ma C, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells recruited by castration-induced inflammation activation accelerate prostate cancer hormone resistance via chemokine ligand 5 secretion. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9(1):242. [32]Dasari S, Fang Y, Mitra AK. Cancer Associated Fibroblasts: Naughty Neighbors That Drive Ovarian Cancer Progression. Cancers (Basel). 2018;10:E406.[33]Tome Y, Tsuchiya H, Hayashi K, et al. In vivo gene transfer between interacting human osteosarcoma cell lines is associated with acquisition of enhanced metastatic potential. J Cell Biochem. 2009;108(2):362-367. [34]Durgan J, Florey O. Cancer cell cannibalism: Multiple triggers emerge for entosis. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2018;1865(6):831-841. [35]Martins I, Raza SQ, Voisin L, et al. Entosis: The emerging face of non-cell-autonomous type IV programmed death. Biomed J. 2017; 40(3):133-140. [36]Khalkar P, Díaz-Argelich N, Antonio Palop J, et al. Novel Methylselenoesters Induce Programed Cell Death via Entosis in Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(10):E2849.[37]Lapitz A, Arbelaiz A, Olaizola P, et al. Extracellular Vesicles in Hepatobiliary Malignancies. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2270. [38]Nawaz M, Shah N, Zanetti BR, et al. Extracellular Vesicles and Matrix Remodeling Enzymes: The Emerging Roles in Extracellular Matrix Remodeling, Progression of Diseases and Tissue Repair. Cells. 2018; 7(10):E167. [39]Choi D, Lee TH, Spinelli C, et al. Extracellular vesicle communication pathways as regulatory targets of oncogenic transformation. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2017;67:11-22.[40]Suetsugu A, Honma K, Saji S, et al. Imaging exosome transfer from breast cancer cells to stroma at metastatic sites in orthotopic nude-mouse models. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013;65(3):383-390. [41]Wang Z, Chen JQ, Liu JL, et al. Exosomes in tumor microenvironment: novel transporters and biomarkers. J Transl Med. 2016;14(1):297.[42]Zhao H, Yang L, Baddour J, et al. Tumor microenvironment derived exosomes pleiotropically modulate cancer cell metabolism. Elife. 2016; 5:e10250. [43]Rackov G, Garcia-Romero N, Esteban-Rubio S, et al. Vesicle-Mediated Control of Cell Function: The Role of Extracellular Matrix and Microenvironment. Front Physiol. 2018;9:651. |

| [1] | Pu Rui, Chen Ziyang, Yuan Lingyan. Characteristics and effects of exosomes from different cell sources in cardioprotection [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(在线): 1-. |

| [2] | Lin Qingfan, Xie Yixin, Chen Wanqing, Ye Zhenzhong, Chen Youfang. Human placenta-derived mesenchymal stem cell conditioned medium can upregulate BeWo cell viability and zonula occludens expression under hypoxia [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(在线): 4970-4975. |

| [3] | Hou Jingying, Yu Menglei, Guo Tianzhu, Long Huibao, Wu Hao. Hypoxia preconditioning promotes bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells survival and vascularization through the activation of HIF-1α/MALAT1/VEGFA pathway [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 985-990. |

| [4] | Shi Yangyang, Qin Yingfei, Wu Fuling, He Xiao, Zhang Xuejing. Pretreatment of placental mesenchymal stem cells to prevent bronchiolitis in mice [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 991-995. |

| [5] | Liang Xueqi, Guo Lijiao, Chen Hejie, Wu Jie, Sun Yaqi, Xing Zhikun, Zou Hailiang, Chen Xueling, Wu Xiangwei. Alveolar echinococcosis protoscolices inhibits the differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells into fibroblasts [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 996-1001. |

| [6] | Fan Quanbao, Luo Huina, Wang Bingyun, Chen Shengfeng, Cui Lianxu, Jiang Wenkang, Zhao Mingming, Wang Jingjing, Luo Dongzhang, Chen Zhisheng, Bai Yinshan, Liu Canying, Zhang Hui. Biological characteristics of canine adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells cultured in hypoxia [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 1002-1007. |

| [7] | Geng Yao, Yin Zhiliang, Li Xingping, Xiao Dongqin, Hou Weiguang. Role of hsa-miRNA-223-3p in regulating osteogenic differentiation of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 1008-1013. |

| [8] | Lun Zhigang, Jin Jing, Wang Tianyan, Li Aimin. Effect of peroxiredoxin 6 on proliferation and differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells into neural lineage in vitro [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 1014-1018. |

| [9] | Zhu Xuefen, Huang Cheng, Ding Jian, Dai Yongping, Liu Yuanbing, Le Lixiang, Wang Liangliang, Yang Jiandong. Mechanism of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells differentiation into functional neurons induced by glial cell line derived neurotrophic factor [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 1019-1025. |

| [10] | Duan Liyun, Cao Xiaocang. Human placenta mesenchymal stem cells-derived extracellular vesicles regulate collagen deposition in intestinal mucosa of mice with colitis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 1026-1031. |

| [11] | Pei Lili, Sun Guicai, Wang Di. Salvianolic acid B inhibits oxidative damage of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and promotes differentiation into cardiomyocytes [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 1032-1036. |

| [12] | Wang Xianyao, Guan Yalin, Liu Zhongshan. Strategies for improving the therapeutic efficacy of mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of nonhealing wounds [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 1081-1087. |

| [13] | Wang Shiqi, Zhang Jinsheng. Effects of Chinese medicine on proliferation, differentiation and aging of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells regulating ischemia-hypoxia microenvironment [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 1129-1134. |

| [14] | Kong Desheng, He Jingjing, Feng Baofeng, Guo Ruiyun, Asiamah Ernest Amponsah, Lü Fei, Zhang Shuhan, Zhang Xiaolin, Ma Jun, Cui Huixian. Efficacy of mesenchymal stem cells in the spinal cord injury of large animal models: a meta-analysis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 1142-1148. |

| [15] | Chen Junyi, Wang Ning, Peng Chengfei, Zhu Lunjing, Duan Jiangtao, Wang Ye, Bei Chaoyong. Decalcified bone matrix and lentivirus-mediated silencing of P75 neurotrophin receptor transfected bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells to construct tissue-engineered bone [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(4): 510-515. |

| Viewed | ||||||

|

Full text |

|

|||||

|

Abstract |

|

|||||