中国组织工程研究 ›› 2013, Vol. 17 ›› Issue (47): 8255-8262.doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-4344.2013.47.018

• 生物材料综述 biomaterial review • 上一篇 下一篇

二氧化钛纳米管的理论研究进展及临床实践

张杭州1,王 琳1,田 昂2,孙 羽1,白希壮1,薛向欣2

- 1中国医科大学附属第一医院运动医学科与关节外科,辽宁省沈阳市 110001;2东北大学材料与冶金学院,辽宁省沈阳市 110001

-

修回日期:2013-08-19出版日期:2013-11-19发布日期:2013-11-19 -

通讯作者:白希壮,博士,博士生导师,主任医师,中国医科大学附属第一医院运动医学科与关节外科,辽宁省沈阳市 110001 zpmhh@sina.com -

作者简介:张杭州☆,男,1984年生,山东省淄博市人,汉族,中国医科大学在读博士,主要从事关节置换、膝关节运动损伤的相关研究。 zhanghz1000@sina.com -

基金资助:国家自然科学基金面上项目(81071449, L2010645)**

Research progress and clinical practice of TiO2 nanotubes

Zhang Hang-zhou1, Wang Lin1, Tian Ang2, Sun Yu1, Bai Xi-zhuang1, Xue Xiang-xin2

- 1Department of Sport Medicine and Joint Surgery, the First Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang 110001, Liaoning Province, China;2 School of Material and Metallurgy, Northeastern University, Shenyang 110001, Liaoning Province, China

-

Revised:2013-08-19Online:2013-11-19Published:2013-11-19 -

Contact:Bai Xi-zhuang, Ph.D., Doctoral supervisor, Chief physician, Department of Sport Medicine and Joint Surgery, the First Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang 110001, Liaoning Province, China zpmhh@sina.com -

About author:Zhang Hang-zhou☆, Studying for doctorate, Department of Sport Medicine and Joint Surgery, the First Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang 110001, Liaoning Province, China zhanghz1000@sina.com -

Supported by:the National Natural Science Foundation of China (General Program), No. 81071449*, L2010645*

摘要:

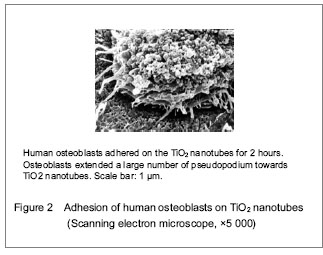

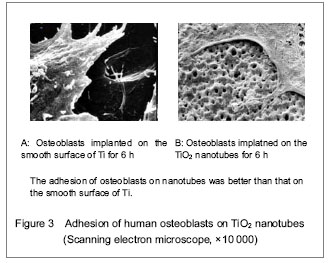

背景:二氧化钛纳米管阵列电化学阳极氧化钛是目前应用前景较好的纳米材料之一。 目的:综述二氧化钛纳米管在临床应用方面的研究进展。 方法:以TiO2 nanotubes,Anodization,biomaterials为检索词,检索PubMed 数据库2000年1月至2013年6月中有关二氧化钛纳米管临床应用领域研究的文献。排除重复研究及陈旧研究,共保留47篇文献进行综述。 结果与结论:从检索到的47篇文献进行总结分析发现,二氧化钛纳米管能够促进包括人成骨细胞,间充质干细胞的黏附和增殖。体内实验证实,二氧化钛纳米管能够促进钛金属内植物在体内的骨整合。此外,二氧化钛纳米管还可作为载体负载其他药物如生长因子和抗生素以促进材料生物形容性及预防细菌黏附。结果说明,二氧化钛纳米管可促进材料的体内骨整合,具有良好的生物相容性。

中图分类号:

引用本文

张杭州,王 琳,田 昂,孙 羽,白希壮,薛向欣. 二氧化钛纳米管的理论研究进展及临床实践[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2013, 17(47): 8255-8262.

Zhang Hang-zhou, Wang Lin, Tian Ang, Sun Yu, Bai Xi-zhuang, Xue Xiang-xin. Research progress and clinical practice of TiO2 nanotubes[J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2013, 17(47): 8255-8262.

TiO2 nanotubes are promising research subjects in the field of material at present. Drug can be delivered to the therapeutic region via nanomaterials effectively, which can overcome adverse distribution in the body, and avoid the defect of systemic medication (such as low efficiency, drug overdose, lack of choice and toxicity).

Totally new tissue culture scaffold can be obtained by changing materials’ appearance. Biologically, interface modification can simplify the complicated biological problems, and can be used as an essential manner for controlling cell behavior. Ti and its alloy surface receive interface modification using anodic oxidation, and TiO2 nanotubes coating can be prepared.

| [1] Darouiche RO. Treatment of infections associated with surgical implants. New Engl J Med. 2004;350(14): 1422-1429.

[2] Gulati K, Aw MS, Findlay D, et al. Local drug delivery to the bone by drug-releasing implants: perspectives of nano-engineered titania nanotube arrays. Ther Deliv. 2012; 3(7):857-873.

[3] Dale H, Hallan G, Hallan G, et al. Increasing risk of revision due to deep infection after hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop. 2009;80(6):639-645.

[4] Lentino JR: Prosthetic joint infections: bane of orthopedists, challenge for infectious disease specialists. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36(9):1157-1161.

[5] Kurtz SM, Lau E, Schmier J, et al. Infection burden for hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23(7):984-991.

[6] Green SA. Complications of external skeletal fixation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;(180):109-116.

[7] Green SA, Ripley MS. Chronic osteomyelitis in pin tracks. J Bone Jt Surg. 1984;66(7):1092-1098.

[8] Diefenbeck M, Mückley T, Hofmann GO. Prophylaxis and treatment of implant-related infections by local application of antibiotics. Injury. 2006;37 Suppl 2:S95-104.

[9] Buchholz HW, Elson RA, Engelbrecht E, et al. Management of deep infection of total hip-replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1981;63(3):342-353.

[10] Donlan RM, Costerton JW. Biofilms: survival mechanisms of clinically relevant microorganisms. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15(2):167-193.

[11] Hall-Stoodley L, Costerton JW, Stoodley P. Bacterial biofilms: from the natural environment to infectious diseases. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2(2):95-108.

[12] Hetrick EM, Schoenfisch MH. Reducing implant-related infections: active release strategies. Chem Soc Rev. 2006;35(9):780-789.

[13] Ribeiro M, Monteiro FJ, Ferraz MP. Infection of orthopedic implants with emphasis on bacterial adhesion process and techniques used in studying bacterial-material interactions. Biomatter. 2012;2(4):176-194.

[14] Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Greenberg EP. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science. 1999; 284:1318-1322.

[15] Mah TF, O’Toole GA. Mechanisms of biofilm resistance to antimicrobial agents. Trends Microbiol. 2001;9(1):34-39.

[16] Davies D. Understanding biofilm resistance to antibacterial agents. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2(2):114-122.

[17] Smith AW. Biofilms and antibiotic therapy: is there a role for combating bacterial resistance by the use of novel drug delivery systems? Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2005;57(10): 1539-1550.

[18] Gilbert P, Collier PJ, Brown MR. Influence of growth rate on susceptibility to antimicrobial agents: biofilms, cell cycle, dormancy, and stringent response. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34(10):1865-1868.

[19] Kendall RW, Duncan CP, Smith JA, et al. Persistence of bacteria on antibiotic loaded acrylic depots.A reason for caution. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;(329):273-280.

[20] Tunney MM, Ramage G, Patrick S, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of bacteria isolated from orthopaedic implants following revision hip surgery. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42(11):3002-3005.

[21] Anagnostakos K, Hitzler P, Pape D, et al. Persistence of bacterial growth on antibiotic-loaded beads: is it actually a problem? Acta Orthop. 2008;79(2):302-307.

[22] Poelstra KA, Barekzi NA, Rediske AM, et al. Prophylactic treatment of gram-positive and gram-negative abdominal implant infections using locally delivered polyclonal antibodies. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;60(1):206-215.

[23] Wu P, Grainger DW. Drug/device combinations for local drug therapies and infection prophylaxis. Biomaterials. 2006;27(11):2450-2467.

[24] Zilberman M, Elsner JJ. Antibiotic-eluting medical devices for various applications. J Control Release. 2008;130(3): 202–215.

[25] Gong DW, Grimes CA, Varghese OK, et al. Titanium oxide nanotube arrays prepared by anodic oxidation. J Mater Res. 2001;16(12):3331-3334.

[26] Losic D, Simovic S. Self-ordered nanopore and nanotube platforms for drug delivery applications. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2009;6(12):1363-1381.

[27] Moseke C, Hage F, Vorndran E, et al. TiO2 nanotube arrays deposited on Ti substrate by anodic oxidation and their potential as a long-term drug delivery system for antimicrobial agents. Applied Surface Science. 2012; 258(14):5399-5404.

[28] Song YY, Schmidt-Stein F, Bauer S, et al. Amphiphilic TiO2 nanotube arrays: an actively controllable drug delivery system. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131(12):4230-4232.

[29] Yang BC, Uchida M, Kim HM, et al. Preparation of bioactive titanium metal via anodic oxidation treatment. Biomaterials. 2004;25(6):1003-1010.

[30] Cooper LF. A role for surface topography in creating and maintaining bone at titanium endosseous implants. J Prosthet Dent. 2000;84(5):522-534.

[31] Webster TJ, Ejiofor JU. Increased osteoblast adhesion on nanophase metals: Ti, Ti6Al4V, and CoCrMo. Biomaterials. 2004;25(19):4731-4739.

[32] Khang D, Choi J, Im YM, et al. Role of subnano-, nano- and submicron-surface features on osteoblast differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Biomaterials. 2012; 33(26):5997-6007.

[33] Jayaraman M, Meyer U, Bühner M, et al. Influence of titanium surfaces on attachment of osteoblast-like cells in vitro. Biomaterials. 2004;25(4):625-631.

[34] Yang H, Qin X, Tian A, et al. Nano Size Effects of TiO2 Nanotube Array on the Glioma Cells Behavior. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;14(1):244-254.

[35] Zhang D, Tian A, Xue X, et al. The effect of temozolomide/ poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA)/nano-hydroxyapatite microspheres on glioma U87 cells behavior. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13(1):1109-1125.

[36] Park J, Bauer S, Schmuki P, et al. Narrow window in nanoscale dependent activation of endothelial cell growth and differentiation on TiO2 nanotube surfaces. Nano Lett. 2009;9(9):3157-3164.

[37] Peng L, Mendelsohn AD, Latempa TJ, et al. Long-term small molecule and protein elution from TiO(2) nanotubes. Nano Lett. 2009;9(5):1932-1936.

[38] Park J, Bauer S, Von Der Mark K, et al. Nanosize and vitality: TiO2 nanotube diameter directs cell fate. Nano Lett. 2007;6:1686-1691.

[39] Park J, Bauer S, Schlegel KA, et al. TiO(2) nanotube surfaces: 15 nm-an optimal length scale of surface topography for cell adhesion and differentiation. Small. 2009; 5(6):666-671.

[40] Oh S, Brammer KS, Li YSJ, et al. Stem cell fate dictated solely by altered nanotube dimension. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(7):2130-2135.

[41] Brammer KS, Seunghan O, Cobb CJ, et al. Improved bone-forming functionality on diameter-controlled TiO2 nanotube surface. Acta Biomater. 2009;5(8):3215-3223.

[42] Popat KC, Leoni L, Grimes CA et al. Influence of engineered titaniananotubular surfaces on bone cells. Biomaterials. 2007;28(21):3188-3197.

[43] von Wilmowsky C, Bauer S, Lutz R et al. In vivo evaluation of anodic TiO2 nanotubes: an experimental study in the pig. J Biomed Mater Res B. 2009;89(1):165-171.

[44] Bjursten LM, Rasmusson L, Oh S, et al. Titanium dioxide nanotubes enhance bone bonding in vivo. J Biomed Mater Res. 2010;92(3):1218-1224..

[45] Popat KC, Eltgroth M, Latempa TJ, et al. Decreased Staphylococcus epidermis adhesion and increased osteoblast functionality on antibiotic-loaded titania nanotubes. Biomaterials. 2007;28(32):4880-4888.

[46] George EA, Chang Y, Thomas JW. Enhanced osteoblast adhesion to drug-coated anodized nanotular titanium safaces. Int J Nanomed. 2008;3(2):257-264.

[47] Park J, Bauer S, PittrofA et al. Synergistic control of mesenchymal stem cell differentiation by nanoscale surface geometry and immobilized growth factors on TiO2 nanotubes. Small. 2012;8(1):98-107. |

| [1] | 洪郭驹,韩晓蕊,方 斌,周广全,何 伟,陈雷雷. 有限元分析运用于股骨头坏死诊断与治疗应用的最新进展[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2017, 21(3): 450-455. |

| [2] | 陈宝林,王东安. 用于心血管医疗装置的聚合物表面构建与生物相容性研究Ⅲ——聚合物生物材料表面的凝血及抗凝血涂层改性[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2015, 19(8): 1277-1283. |

Retrieval strategy

A total 47 literatures were included[1-47]. The effects of TiO2 nanotube on reducing inflammation and infection and in elevating biocompatibility and osseointegration were summarized.

1 此问题的已知信息:二氧化钛纳米管显著的优越性能逐渐成为目前一个最有吸引力的生物材料,在医学内植物研究中有着良好的前景。 2 文章增加的新信息:目前学者们正通过各种方式对假体材料进行改进与修饰,以求降低材料的感染率,并增强其与骨组织的整合能力。 3 临床应用的意义:随着假体材料的不断推陈出新,二氧化钛纳米管若能在临床应用中取得突破性进展,定将会在人工关节置换领域得到广泛应用。

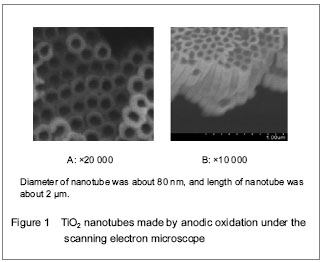

文章特点:综述目前二氧化钛纳米管在临床相关研究的进展,结果显示二氧化钛纳米管在体内外的相关研究中显示出良好的生物相容性及骨整合能力。二氧化钛纳米管阵列由电化学阳极氧化技术制备。由于二氧化钛纳米管显著的优越性能逐渐成为目前一个最有吸引力的生物材料。文章将重点介绍作为局部药物载体的二氧化钛纳米管阵列的临床应用,特别是应用于骨科内植物。

| 阅读次数 | ||||||

|

全文 |

|

|||||

|

摘要 |

|

|||||