Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research ›› 2019, Vol. 23 ›› Issue (16): 2545-2552.doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-4344.1212

Previous Articles Next Articles

Development and prevention strategy of proximal junctional kyphosis after scoliosis surgery

Dai Jianjun1, Xing Wenhua2

- 1Graduate School of Inner Mongolia Medical University, Hohhot 010000, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, China; 2the Second Affiliated Hospital of Inner Mongolia Medical University, Hohhot 010000, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, China

-

Online:2019-06-08Published:2019-06-08 -

Contact:Xing Wenhua, MD, Chief physician, the Second Affiliated Hospital of Inner Mongolia Medical University, Hohhot 010000, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, China -

About author:Dai Jianjun, Master candidate, Graduate School of Inner Mongolia Medical University, Hohhot 010000, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, China -

Supported by:the National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 81460344 (to XWH)| the Natural Science Foundation of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, No. 2018MS08095 (to XWH)

CLC Number:

Cite this article

Dai Jianjun, Xing Wenhua. Development and prevention strategy of proximal junctional kyphosis after scoliosis surgery[J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2019, 23(16): 2545-2552.

share this article

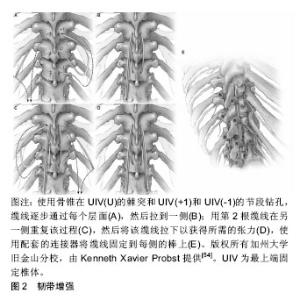

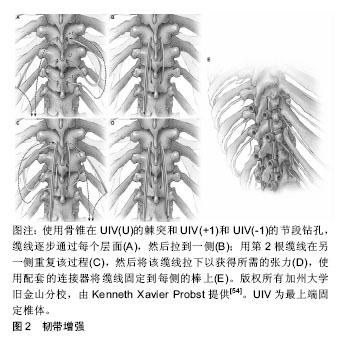

2.1 近端交界性后凸畸形的定义 为了诊断近端交界性后凸畸形,应首先确定近端交界性后凸畸形适当的定义。1994年Lowe等[1]首次将近端交界性后凸描述为休门氏病(Scheuermann’s disease)脊柱后凸畸形手术的并发症,即在脊柱矫形术后,内固定近端后凸逐渐增大。1999年Lee等[2]首次对青少年特发性脊柱侧凸进行了影像学的定义。明确了近端交界性后凸畸形的概念,认为最上端固定椎体(upper instrumented vertebra,UIV)与其近端第1个椎体(UIV+1)间的后凸角较术后增加超过5°即可称为近端交界性后凸畸形。但是,近端交界性后凸畸形的各种定义尚未统一。此后,2005年Glattes等[3]将近端交界性后凸畸形的定义完善为近端交界区后凸角,即UIV的下终板与UIV+2的上终板之间的后凸角,超过10°以上,并且比术前测量结果至少大于10°。但是Hostin等[4]根据回顾性研究的结果,将近端交界性后凸畸形定义为近端交界区后凸角较术前超过15°。O'Shaughnessy等[5]和Bridwell等[6]将近端交界性后凸畸形定义为“近端交界区后凸角较术前超过20°”。2010年Helgeson等[7]认为,UIV的下终板与UIV+1(而不是UIV+2)的上终板之间的后凸角度较术前超过15°即可称为近端交界性后凸畸形。迄今为止,Glattes等[3]对近端交界性后凸畸形的定义似乎是文献中最常用的。 Sacramento-Dominguez等[8]评估使用UIV+1和UIV+2测量近端交界性后凸畸形的可靠性。虽然它们表现出中度到高度的可靠性,但作者不能断定哪一种是测量近端交界性后凸畸形的更好标志[8]。最近的研究表明,在上胸椎或胸腰交界区,有或没有近端交界性失败,从UIV到UIV+2脊柱后凸畸形的影像学测量具有高度的可靠性[9]。 近年Kim等[10]提出了近端交界性失败的概念,指伴有临床症状和近端交界区结构性失败的近端交界性后凸畸形。近端交界性失败比近端交界性后凸畸形更严重,并且被认为是成人脊柱畸形术后再次手术的最常见原因之一。Hart等[11]根据UIV和UIV+2之间后凸角较术后增加超过10°,描述了近端交界性失败如下特征:UIV或UIV+1椎体骨折,后方韧带复合体损伤或内置物脱出或断裂。Yagi等[12]将近端交界性失败定义为一种症状性近端交界性后凸畸形,并且需要进行翻修手术。 2.2 近端交界性后凸畸形的发生率 近端交界性后凸畸形的发生率在不同的报道中有所差异。Hostin等[4]在研究中发现,1 218例患者近端交界性后凸畸形发生率为6%,这是可用医学文献报道中最低发生率。Glattes等[3]报道了81例成人脊柱畸形患者,平均随访5.3年后,近端交界性后凸畸形发生率为26%。Raman等[13]研究纳入了39例患者,其中28.2%发生了近端交界性后凸畸形。Kim等[14]对161例脊柱矫形术后患者进行7.8年随访后,近端交界性后凸畸形发生率为39%。Yagi等[15]报道157例成人特发性脊柱侧凸患者,平均随访4.3年后,近端交界性后凸畸形发生率为20%。Maruo等[16]报道90例成人特发性脊柱侧凸患者近端交界性后凸畸形发生率为41%。Bridwell等[6]报道了近端交界性后凸畸形发生率为28%。近端交界性后凸畸形的发病率也因UIV的水平而异。O'Shaughnessy等[5]研究了2002至2006年期间接受成人脊柱侧凸手术的58例患者,得出最上端固定椎为下胸椎时近端交界性后凸畸形发生率为18.4%;最上端固定椎为上胸椎时近端交界性后凸畸形发病率为10%。Sebaaly等[17]研究了314例后路矫形的脊柱侧凸患者,近端交界性后凸畸形的发生率为25%。Nicholls等[18]将平均随访34个月的440例患者纳入评价标准,其中159例发生近端交界性后凸畸形(36%),65例需要修复手术(41%)。在Luo等[19]的Meta分析中,纳入了包括1 230例患者的回顾性研究,总近端交界性后凸畸形率为32.2%。Liu等[20]的Meta分析包括2 215例患者,据报道近端交界性后凸畸形的总发生率为30%,其研究中招募的大多数邻近节段病患者在2010至2014年期间接受了手术治疗。Lafage等[21]研究了679例患者,近端交界性后凸畸形总发生率是45.1%。脊柱矫形手术后随着时间推移会出现近端交界性后凸畸形。Kim等[14]认为近端交界性后凸畸形在手术后8周内出现;而Yagi等[22]报道,66%的近端交界性后凸畸形病例在3个月内出现;Wang等[23]则指出,在18个月内可以诊断为近端交界性后凸畸形的病例为80%。 近端交界性后凸畸形不仅仅是一种影像学改变,但是否对患者具有潜在的临床意义值得进一步验证。大多数研究未能证明发生近端交界性后凸畸形组患者与未发生近端交界性后凸畸形组患者具有显著临床差异[3,5-6]。Kim等[14]报道,当近端交界性后凸畸形> 20°时,近端交界性后凸畸形组的脊柱侧凸研究学会评分更差。随后的一项大型回顾性研究中,Kim等[24]发现近端交界性后凸畸形组患者的疼痛发生率(29.4%)高于未出现近端交界性后凸畸形组患者(0.9%)。Yagi等[15]报道,近端交界性后凸畸形组与非近端交界性后凸畸形组差异无显著性意义,但在有症状的近端交界性后凸畸形患者中脊柱侧凸研究学会评分和Oswestry功能障碍指数更差。还有证据表明,近端交界性后凸畸形可以是渐进的,并且近端交界性后凸畸形角度的增加(在某些情况下可能提示结构性失败)与疼痛呈正相关,并与功能呈负相关[22,24]。 总之,报道的所有发病率为6%-45.1%[3-6,13-21],更多的研究倾向于20%-40%[3,6,13-15,17-20]。 2.3 近端交界性后凸畸形发病机制及危险因素 2.3.1 近端交界性后凸畸形的发病机制 回顾相关文献,一般机制包括以下内容[3,14,22,25-26]:①最上端固定椎广泛的椎旁肌肉剥离;②后方韧带复合体的破坏;③固定端椎选择不当;④近端严重椎间盘退变;⑤压缩性骨折;⑥近端椎体内固定失败;⑦小关节紊乱。此外,为了更好地了解近端交界性后凸畸形的发病机制,许多研究调查了近端交界性后凸畸形的危险因素。 2.3.2 近端交界性后凸畸形的危险因素 手术时患者的年龄较大是与近端交界性后凸畸形相关的风险因素,最近的数据表明55岁以上的患者发生近端交界性后凸畸形的风险增加[14,20,27-28]。此外,高龄被认为是近端交界性后凸畸形翻修手术的危险因素[29]。更重要的是,Lafage等[30]最近的一项工作发现,近端交界性后凸畸形发生率从40岁前的<15%增加到65岁前的>55%。然而,Lafage等[21]发现这些患者的近端交界性后凸畸形很可能是矢状面矫正过度造成的。此外术前存在大范围的矢状位失衡和畸形程度也被认为是近端交界性后凸畸形和近端交界性失败的危险因素。术前高度的矢状位垂直轴和胸椎后凸角是特别值得注意的参数[31]。这强调了患者需要特异性治疗的必要性,与年轻患者相比,尤其是对老年患者的年龄和过度畸形需要不同评价标准[21]。 关于体质量指数在近端交界性后凸畸形发生中的作用,大量学者存在强烈的共识[32-34]。进展为近端交界性后凸畸形的潜在因素可以通过体质量增加引起身体重心向前移位来解释,从而增加近端未融合脊柱的应力负荷[22,34]。目前,没有研究对近端交界性后凸畸形风险增加的体质量指数临界值进行量化。 多项研究将低骨密度作为近端交界性后凸畸形的危险因素[20,34-35]。就骨质量而言,骨质疏松患者的骨与螺钉连接面较弱,增加了内置螺钉脱出的风险。由于低骨密度导致的脊柱融合术后相邻节段疾病的风险已有详细记录。骨质疏松症也与肌肉萎缩有关,而且较低的骨密度与胸腰段肌肉组织减少相关,有可能导致脊柱不稳定并加速近端交界性后凸畸形的发展[22,34]。 合并症的存在是近端交界性后凸畸形的危险因素之一[33]。Diebo等[36]利用全国住院病例中的几个参数,开发了一种新的指标来量化邻近节段病手术的整体发病风险。肺循环和神经系统疾病以及其他疾病被确定为邻近节段病风险的因素,有必要进一步研究单个合并症在近端交界性后凸畸形发展中所起的作用,这些指数将有助于近端交界性后凸畸形患者的术前预防。Scheer等[37]开发了一种模型,该模型可以预测临床意义上的近端交界性后凸畸形或近端交界性失败,其准确率为86%。这些可帮助外科医生对有近端交界性后凸畸形/近端交界性失败风险因素的患者进行个体化治疗。 若干尸体和生物力学研究表明近端交界性后凸畸形的发展与后方软组织和椎间因素破坏有关[31,38]。前后路联合手术也被认为是近端交界性后凸畸形的危险因素[33]。更大的畸形矫正幅度也与近端交界性后凸畸形增加有关[33,39]。多项研究得出结论认为,腰椎前凸角和矢状位垂直轴过度矫正均促进了近端交界性后凸畸形的发生[31,33,39]。这些结果与大多数作者的发现是一致的。事实上,Yagi等[22]发现术前失衡增加和矢状位垂直轴> 5 cm会增加这种并发症的风险,而Kim等[29]发现近端交界性后凸畸形发生率随着矫正幅度增加而增加(矢状位垂直轴> 8 cm)。 Dubouset的理论有助于解释这一点:在校正过程中,矢状面过度矫正会破坏矢状位垂直轴和自然重力之间的平衡。身体试图自我纠正到最佳位置,但使未融合的部分承担了更大的受力,这可能是近端交界性后凸畸形发生的推动力,强调了手术计划对个体患者的重要性[40]。矢状平衡的最佳矫正被认为是成人畸形矫正和腰椎融合手术取得成功的关键因素[41]。对于近端交界性后凸畸形和近端交界性失败,一些作者认为术后最佳矢状平衡是近端交界性后凸畸形的保护因素。Lafage等[21]根据年龄进行了调整,发现患有近端交界性后凸畸形的所有患者都表现出了过度矫正,揭示了过度矫正和近端交界性后凸畸形之间的联系。过度矫正曾经是老年患者对抗退变性疾病的最有利因素,但它并没有对患者的年龄及术后预期进行合理的规划。因此,更全面的术前计划可能会减少近端交界性后凸畸形风险[21]。矫正的范围会影响近端交界性后凸畸形的发生率。Sebaaly等[17]研究得出,融合范围从骶骨延伸到上胸椎水平是近端交界性后凸畸形的危险因素。文献一致报道胸腰段交界处,尤其是T11和L1之间的UIV选择与近端交界性后凸畸形相关。这可能是因为从较不灵活的胸椎和肋骨向更具活动性的腰椎过渡所致[33-34]。除此之外,深入了解UIV的选择是有必要的。Lafage等[42]证实,患者的UIV在下胸段时近端交界性后凸畸形的发生率和风险显著增加。同时近端交界性后凸畸形患者表现出更大的后凸倾向,适当的连接棒可能会降低近端交界性后凸畸形风 险[42]。 总之,近端交界性后凸畸形发生的危险因素可分为不可控制因素和可控制因素2类[14,20-21,27-42]。不可控制因素包括:①年龄大于55岁;②体质量指数过大;③低骨密度;④术前矢状位失衡;⑤合并多种疾病。可控制因素包括:①前后路联合手术;②后方韧带复合体损伤;③过度矫正;④融合范围过大;⑤采用内置物的类型和组合。 2.4 近端交界性后凸畸形的预防 2.4.1 椎体成形术 为了强化骨骼,Martin等[43]进行了一项前瞻性研究,评估41例手术治疗的邻近节段病患者,使用骨水泥增加UIV和UIV+1的预防作用,并报道邻近节段病患者的预防性椎体成形术将近端交界性失败发生率降低至5%。Raman等[13]研究随访了39例进行椎体成形术的患者5年时间,发现椎体成形术可能使术后早期交界性失败的风险降至最低,并且似乎对近端交界性后凸畸形的发展或晚期失败没有任何影响。Kebaish等[44]证明了在UIV及UIV+1行预防性椎体成形术,在尸体模型中显著减少了椎体骨折的发生率,进而降低近端交界性后凸畸形的出现。虽然尸体模型排除了对临床近端交界性后凸畸形发生率的直接预测,但这些发现具有指导意义。Theologis等[45]评估了在邻近节段病患者的UIV及UIV+1两节段上进行水泥增强,这种方法显著降低了椎体骨折,从而减少了因近端交界性失败而进行翻修手术。此外他们发现在未使用骨水泥或未进行2节段(UIV、UIV+1)骨水泥增强的患者中,近端交界性后凸畸形翻修手术的可能性增加。Ghobrial等[46]将85例成人邻近节段病患者分成A和B组。A组47例患者未进行骨水泥强化,B组38例患者在UIV和UIV+1两节段行骨水泥强化,最终结果显示近端交界性后凸畸形的角度在A组中更大(9.36°vs.5.65°),近端交界性后凸畸形的发生率在A和B组中分别为36% (n=17)和23.7%(n=9)。畸形矫正时使用骨水泥增强UIV和UIV+1椎体,可减少患者中近端交界性后凸畸形和近端交界性失败的发生率。然而值得注意的是,单独进行1个节段的骨水泥增强会增加其邻近椎体的压力。在UIV使用骨水泥增强,增加了UIV+1的压力,进而增加近端交界性后凸畸形的风险[47]。相反,在UIV和UIV+1处的椎体成形术可以缓冲轴向压力,并将压力传播到其他节段来保护UIV+1[44]。 尽管椎体成形术具有令人信服的生物力学原理,但这种技术还是有局限性的。骨水泥阻断了椎体内血供,减少邻近椎间盘的营养供应,从而加速退行性疾病的发生[48]。通过这种技术改变载荷传递的机制,也有可能导致相邻节段的骨折和塌陷[47]。 2.4.2 横突钩 在UIV中使用骨钩代替椎弓根螺钉是另一种公认的近端交界性后凸畸形预防策略。骨钩提供了理论上的优势,因为它们减少周围肌肉和小关节的显露,并在结构的顶部提供更动态的固定[7,24,49]。几项研究比较了在UIV使用骨钩固定和使用椎弓根螺钉患者的近端交界性后凸畸形发生率。使用椎弓根螺钉患者近端交界性后凸畸形发生率为30%-35%,而使用骨钩固定患者近端交界性后凸畸形发生率为0%-30%[7,50]。 Pahys等[50]研究了354例患者,螺钉组274例(77%),骨钩组80例(23%),螺钉组术后T5-T12后凸畸形较骨钩组明显减少(P=0.016)。在青少年特发性脊柱侧凸中,使用椎弓根螺钉与骨钩相比,在冠状面矫正方面有显著的改善。然而椎弓根螺钉可能对术后矢状面平衡产生负面影响。Clements等[51]报道,椎弓根螺钉可显著减少术后胸椎后凸畸形,而骨钩可增加术后胸椎后凸畸形。术后胸椎后凸畸形的减少被认为可能有助于近端交界性后凸畸形的发展以及腰椎前凸的减少[52]。 Hassanzadeh等[53]回顾了47例长节段固定术后的患者,在2年的随访中发现,椎弓根螺钉内固定组术后近端交界性后凸畸形发生率(26.9%)明显高于横突钩组(0%)。因此在UIV上使用骨钩可降低近端交界性后凸畸形的发生。 2.4.3 韧带加强 Safaee等[54]研究了100例接受韧带增强技术的患者,近端交界角的平均变化在韧带增强组为6°,而对照组为14°,差异有显著性意义(P < 0.001)。根据数据显示,与历史对照组相比,使用韧带增强技术与近端交界性后凸畸形和近端交界性失败的减少相关。这些结果为实施韧带增强提供了令人信服的理由。此次研究数据支持在成人脊柱畸形手术中实施韧带增强,见图2,特别是具有近端交界性后凸畸形和近端交界性失败高风险因素的患者。Pham等[55]报道了一种新型的棘突间韧带增强技术,该技术使用尸体半腱肌腱移植物通过Krackow缝合法编织并固定。他们研究了4例接受这种移植技术的患者,平均随访时间为5.5个月,直到刊物发表未出现近端交界性后凸畸形。因此在近端邻近水平的椎间韧带增强与尸体半腱肌腱移植是防止近端交界性后凸的可行策略。该研究需要更多的临床数据和更长时间的随访,来确定此技术是否是预防成人脊柱畸形患者近端交界性后凸畸形的持久选择。Zaghloul等[56]报道共有23例患者使用Mersilene线带在融合节段近端进行固定。初步数据表明,使用这种技术可以防止近端交界后凸畸形的形成。"

旨在增强韧带的技术被证明是有效的,因为在近端交界性后凸畸形和近端交界性失败的发病机制中,后韧带复合体的破坏被认为是一个重要的因素。韧带增强的目的是为UIV,UIV+1和UIV-1水平提供强度,同时还减少了这些节段的交界区应力,并加强后韧带复合体。这种技术显示早期近端交界性后凸畸形有显著减少,但是需要长期的数据。 2.4.4 近端交界性后凸畸形的其他预防策略 Zhao 等[57]研究了近端交界性后凸畸形的主要危险因素,并引入一个新的近端交界性后凸畸形预测指标,分析了2010年1月至2015年1月接受矫正手术的62例邻近节段病患者的病历资料。根据ROC曲线,近端交界性后凸畸形指数作为近端交界性后凸畸形发生指标的最佳值为-2。如果近端交界性后凸畸形指数小于-2,则近端交界性后凸畸形发生率为82%;相反,没有近端交界性后凸畸形的比例是95%。在矫正手术前可根据其回归分析结果制定手术计划。首先,应考虑术前胸腰后凸角,如果术前胸腰后凸角大于10°,应选择跨越胸腰段后凸的UIV以避免近端交界性后凸畸形,UIV也不应该选择在胸腰椎后凸的顶点。其次,应进行适度的腰椎前凸矫正。一方面,手术后腰椎前凸过大可能导致矢状面后倾,导致近端交界性后凸畸形发生恢复矢状面平衡;另一方面,过度矫正后凸畸形也可能导致腰椎前凸过度减少,最终的腰椎前凸可能与患者的骨盆入射角无法匹配,这种不匹配导致近端交界性后凸畸形的风险增加。此外,胸腰后凸角和腰椎前凸角的校正决定了骨盆旋转,即随访时的骨盆倾斜角/骶骨倾斜角。但术前骨盆倾斜角/骶骨倾斜角在手术前已经存在,不能通过矫正手术来改变,因此说明了矫正手术期间矫正胸腰后凸角和腰椎前凸角的重要性。回归分析结果显示,术前胸腰后凸角、随访腰椎前凸角、术前骨盆倾斜角/骶骨倾斜角和随访骨盆倾斜角/骶骨倾斜角是近端交界性后凸畸形的主要因素,近端交界性后凸畸形指数可以有效地预测近端交界性后凸畸形的发生。因此,建议在矫正手术时应考虑脊柱和骨盆参数的矫正,而不是只关注脊柱参数。 在其他学者的研究中,不同椎弓根钉棒系统的选择也可影响近端交界性后凸畸形的进展。Han等[27]研究脊柱结构刚度,发现钴铬多棒结构与钛双棒结构相比,表现出更强的连接棒刚度,提高结构稳定性并减少断棒的可能。然而钴铬多棒结构增加棒的刚度,同时增加了近端交界性后凸畸形发生的风险并影响了近端交界性后凸畸形的进展。钛双棒结构患者在2-84个月内发生近端交界性后凸畸形,而钴铬多棒结构患者的近端交界性后凸畸形病例均在术后7个月内发生[27]。Zhu等[58]通过研究得出在休门氏病(Scheuermann’s disease)脊柱后凸畸形患者中,使用卫星棒(S-RC)技术是一种安全有效的方法,可以降低近端交界性后凸畸形的发生率。"

| [1] Lowe TG, Kasten MD. An analysis of sagittal curves and balance after Cotrel-Dubousset instrumentation for kyphosis secondary to Scheuermann’s disease: a review of 32 patients. Spine. 1994;19: 1680-1685.[2] Lee GA, Betz RR, Clements DH 3rd, et al. Proximal kyphosis after posterior spinal fusion in patients with idiopathic scoliosis. Spine. 1999;24: 795-799.[3] Glattes RC, Bridwell KH, Lenke LG, et al. Proximal junctional kyphosis in adult spinal deformity following long instrumented posterior spinal fusion: incidence, outcomes and risk factor analysis. Spine. 2005; 30: 1643-1649.[4] Hostin R, McCarthy I, O’Brien M, et al. Incidence, mode, and location of acute proximal junctional failures after surgical treatment of adult spinal defor-mity.Spine.2013;38: 1008-1015.[5] O?Shaughnessy BA, Bridwell KH, Lenke LG, et al. Does a long-fusion "T3-sacrum" portend a worse outcome than a short-fusion "T10-sacrum" in primary surgery for adult scoliosis? Spine.2012;37: 884-890.[6] Bridwell KH,Lenke LG,Cho SK, et al. Proximal junctional kyphosis in primary adult deformity surgery: evaluation of 20 degrees as a critical angle. Neurosurgery. 2013;72: 899-906.[7] Helgeson MD, Shah SA, Newton PO, et al. Evaluation of proximal junctional kyphosis in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis following pedicle screw, hook, or hybrid instrumentation. Spine. 2010;35:177-181.[8] Sacramento-Domínguez C, Vayas-Díez R, Coll-Mesa L, et al. Reproducibility measuring the angle of proximal junctional kyphosis using the first or the second vertebra above the upper instrumented vertebrae in patients surgically treated for scoliosis. Spine. 2009;34: 2787-2791.[9] Rastegar F,Contag A,Daniels A, et al. Proximal junctional kyphosis: inter- and intra-observer reliability of radiographic measurements in adult spinal deformity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2017. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000002261.[10] Kim HJ,Lenke LG,Shaffrey CI, et al. Proximal junctional kyphosis as a distinct form of adjacent segment pathology after spinal deformity surgery: a systematic review.Spine. 2012;37: S144-164.[11] Hart RA,McCarthy I,Ames CP, et al. Proximal junctional kyphosis and proximal junctional failure. Neurosurg. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2013;24(2):213-218.[12] Yagi M, Rahm M, Gaines R, et al. Characterization and surgical outcomes of proximal junctional failure in surgically treated patients with adult spinal deformity. Spine. 2014;39: E607-614.[13] Raman T,Miller E,Martin CT, et al. The effect of prophylactic vertebroplasty on the incidence of proximal junctional kyphosis and proximal junctional failure following posterior spinal fusion in adult spinal deformity: a 5-year follow-up study. Spine J. 2017;17: 1489-1498.[14] Kim YJ, Bridwell KH, Lenke LG, et al. Proximal junctional kyphosis in adult spinal deformity after segmental posterior spinal instru- mentation and fusion: minimum five-year follow-up. Spine. 2008; 33:2179-2184. [15] Yagi M, Akilah KB, Boachie-Adjei O. Incidence, risk factors and classification of proximal junctional kyphosis: surgical outcomes review of adult idiopathic scoliosis.Spine.2011;36: E60-68.[16] Maruo K,Ha Y,Inoue S, et al. Predictive factors for proximal junctional kyphosis in long fusions to the sacrum in adult spinal deformity.Spine. 2013;38: E1469-1476.[17] Sebaaly A,Sylvestre C,El Quehtani Y, et al. Incidence and risk factors for proximal junctional kyphosis: results of a multicentric study of adult scoliosis. Clin Spine Surg. 2018; 31: E178-E183.[18] Nicholls FH,Bae J,Theologis AA, et al. Factors associated with the development of and revision for proximal junctional kyphosis in 440 consecutive adult spinal deformity patients. Spine.2017; 42: 1693-1698.[19] Luo M,Wang P,Wang W, et al. Upper thoracic versus lower thoracic as site of upper instrumented vertebrae for long fusion surgery in adult spinal deformity: a meta-analysis of proximal junctional kyphosis. World Neurosurg. 2017; 102: 200-208.[20] Liu Fe,Wang T,Yang SD, et al. Incidence and risk factors for proximal junctional kyphosis: a meta-analysis.Eur Spine J. 2016;25: 2376-2383.[21] Lafage R,Schwab F,Glassman S,et al. Age-adjusted alignment goals have the potential to reduce PJK.Spine. 2017;42: 1275-1282.[22] Yagi M,King AB,Boachie-Adjei O. Incidence, risk factors, and natural course of proximal junctional kyphosis: surgical outcomes review of adult idiopathic scoliosis. Minimum 5 years of follow-up. Spine. 2012;37: 1479-1489.[23] Wang J,Zhao Y,Shen B, et al. Risk factor analysis of proximal junctional kyphosis after posterior fusion in patients with idiopathic scoliosis.Injury. 2010; 41: 415-420.[24] Kim HJ,Bridwell KH,Lenke LG, et al. Proximal junctional kyphosis results in inferior SRS pain subscores in adult deformity patients. Spine. 2013;38: 896-901.[25] Anderson AL, McIff TE, Asher MA, et al. The effect of posterior thoracic spine anatomical structures on motion segment flexion stiffness.Spine. 2009;34: 441-446.[26] Arlet V,Aebi M, Junctional spinal disorders in operated adult spinal deformities: present understanding and future perspectives. Eur Spine J. 2013;22 Suppl 2:S276-295.[27] Han S, Hyun SJ, Kim KJ, et al. Rod stiffness as a risk factor of proximal junctional kyphosis after adult spinal deformity surgery: comparative study between cobalt chrome multiple-rod constructs and titanium alloy two-rod constructs. Spine. Spine J. 2017;17(7): 962-968.[28] Lau D,Clark AJ,Scheer JK, et al. Proximal junctional kyphosis and failure after spinal deformity surgery: a systematic review of the literature as a background to classification development.Spine. 2014;39: 2093-2102.[29] Kim HJ,Bridwell KH,Lenke LG, et al. Patients with proximal junctional kyphosis requiring revision surgery have higher postoperative lumbar lordosis and larger sagittal balance corrections. Spine. 2014;39: E576-580.[30] Lafage R,Schwab F,Challier V, et al. Defining spino-pelvic alignment thresholds: should operative goals in adult spinal deformity surgery account for age? Spine. 2016; 41: 62-68.[31] Kim HJ, Iyer S. Proximal junctional kyphosis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2016;24: 318-326.[32] Lau D, Clark AJ, Scheer JK, et al. Proximal junctional kyphosis and failure after spinal deformity surgery: a systematic review of the literature as a background to classification development. Spine. 2014; 39(25):2093-2102.[33] Park SJ, Lee CS, Chung SS, et al. Different risk factors of proximal junctional kyphosis and proximal junctional failure following long instrumented fusion to the sacrum for adult spinal deformity: survivorship analysis of 160 patients. Neurosurgery. 2017; 80: 279-286.[34] Kim DK, Kim JY, Kim DY, et al. Risk factors of proximal junctional kyphosis after multilevel fusion surgery: more than 2 years follow-up data. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2017; 60: 174-180.[35] Yagi M,Fujita N,Tsuji O, et al. Low bone-mineral density is a significant risk for proximal junctional failure after surgical correction of adult spinal deformity: a propensity score-matched analysis. Spine. 2018; 43: 485-491.[36] Diebo BG, Jalai CM, Challier V, et al. Novel index to quantify the risk of surgery in the setting of adult spinal deformity: a study on 10,912 patients from the nationwide inpatient sample. Clin Spine Surg. 2017;30: E993-E999.[37] Scheer JK,Osorio JA,Smith JS, et al. Development of validated computer-based preoperative predictive model for proximal junction failure (pjf) or clinically significant pjk with 86% accuracy based on 510 asd patients with 2-year follow-up. Spine. 2016; 41: E1328-E1335.[38] Lange T, Schulte TL, Gosheger G, et al. Effects of multilevel posterior ligament dissection after spinal instrumentation on adjacent segment biomechanics as a potential risk factor for proximal junctional kyphosis: a biomechanical study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2018; 19(1): 57.[39] Scheer JK, Lafage R, Schwab FJ, et al. Under correction of sagittal deformities based on age-adjusted alignment thresholds leads to worse health-related quality of life whereas over correction provides no additional benefit. Spine. 2018; 43: 388-393.[40] Lafage R, Bess S, Glassman S,et al. Virtual modeling of postoperative alignment after adult spinal deformity surgery helps predict associations between compensatory spinopelvic alignment changes, overcorrection, and proximal junctional kyphosis. Spine. 2017;42: E1119-E1125.[41] Masevnin S, Ptashnikov D, Michaylov D, et al. Risk factors for adjacent segment disease development after lumbar fusion. Asian Spine J. 2015; 9(2): 239-244.[42] Lafage R, Line BG, Gupta S, et al. Orientation of the upper-most instrumented segment influences proximal junctional disease following adult spinal deformity surgery. Spine. 2017;42: 1570-1577.[43] Martin CT, Skolasky RL,Mohamed AS, et al. Preliminary results of the effect of prophylactic vertebroplasty on the incidence of proximal junctional complications after posterior spinal fusion to the low thoracic spine. Spine Deform. 2013;1: 132-138.[44] Kebaish KM,Martin CT,O'Brien JR, et al. Use of vertebroplasty to prevent proximal junctional fractures in adult deformity surgery: a biomechanical cadaveric study. Spine J. 2013;13: 1897-1903.[45] Theologis AA,Burch S. Prevention of acute proximal junctional fractures after long thoracolumbar posterior fusions for adult spinal deformity using 2-level cement augmentation at the upper instrumented vertebra and the vertebra 1 level proximal to the upper instrumented vertebra. Spine. 2015; 40: 1516-126.[46] Ghobrial GM,Eichberg DG,Kolcun JPG, et al. Prophylactic vertebral cement augmentation at the uppermost instrumented vertebra and rostral adjacent vertebra for the prevention of proximal junctional kyphosis and failure following long-segment fusion for adult spinal deformity. Spine J. 2017; 17: 1499-1505.[47] Watanabe K,Lenke LG,Bridwell KH, et al. Proximal junctional vertebral fracture in adults after spinal deformity surgery using pedicle screw constructs: analysis of morphological features. Spine. 2010; 35: 138-145.[48] Verlaan JJ,Oner FC,Slootweg PJ, et al. Histologic changes after vertebroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A(6):1230-1238.[49] Kim YJ,Bridwell KH,Lenke LG, et al. Proximal junctional kyphosis in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis following segmental posterior spinal instrumentation and fusion: minimum 5-year follow-up. Spine. 2005; 30: 2045-2050.[50] Pahys JM,Vivas AC,Samdani AF, et al. Assessment of proximal junctional kyphosis and shoulder balance with proximal screws versus hooks in posterior spinal fusion for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine. 2018;43: E1322-E1328.[51] Clements DH,Betz RR,Newton PO, et al. Correlation of scoliosis curve correction with the number and type of fixation anchors. Spine. 2009;34: 2147-2150.[52] Newton PO,Yaszay B,Upasani VV, et al. Preservation of thoracic kyphosis is critical to maintain lumbar lordosis in the surgical treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine. 2010;35: 1365-1370.[53] Hassanzadeh H, Gupta S, Jain A, et al. Type of anchor at the proximal fusion level has a significant effect on the incidence of proximal junctional kyphosis and outcome in adults after long posterior spinal fusion. Spine Deform. 2013;1(4): 299-305.[54] Safaee MM, Deviren V, Dalle Ore C, et al. Ligament augmentation for prevention of proximal junctional kyphosis and proximal junctional failure in adult spinal deformity. J Neurosurg Spine. 2018;28: 512-519.[55] Pham MH, Tuchman A, Smith L,et al. Semitendinosus graft for interspinous ligament reinforcement in adult spinal deformity. Orthopedics. 2017; 40: e206-e210.[56] Zaghloul KM, Matoian BJ, Denardin NB, et al. Preventing proximal adjacent level kyphosis with strap stabilization. Orthopedics. 2016;39: e794-7999.[57] Zhao J, Yang M, Yang Y, et al. Proximal junctional kyphosis in adult spinal deformity: a novel predictive index. Eur Spine J. 2018;27: 2303-2311.[58] Zhu ZZ , Chen X , Qiu Y, et al. Adding satellite rods to standard 2-rod construct with the use of duet screws: an effective technique to improve surgical outcomes and preventing proximal junctional kyphosis in posterior-only correction of scheuermann kyphosis. Spine. 2017.[59] Hart R, McCarthy I, O?brien M, et al. Identification of decision criteria for revision surgery among patients with proximal junctional failure after surgical treatment of spinal deformity. Spine. 2013;38: E1223-1227. |

| [1] |

Zhang Cong, Zhao Yan, Du Xiaoyu, Du Xinrui, Pang Tingjuan, Fu Yining, Zhang Hao, Zhang Buzhou, Li Xiaohe, Wang Lidong.

Biomechanical analysis of the lumbar spine and pelvis in adolescent

idiopathic scoliosis with lumbar major curve |

| [2] | He Yujie, Wang Haiyan, Li Zhijun, Li Xiaohe, Cai Yongqiang, Dai Lina, Xu Yangyang, Wang Yidan, Xu Xuebin. Digital measurements of the anatomical parameters of pedicle-rib unit screw fixation in thoracic vertebrae of preschoolers [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2020, 24(6): 869-876. |

| [3] | Sun Jian, Fang Chao, Gao Fei, Wei Laifu, Qian Jun. Clinical efficacy and complications of short versus long segments of internal fixation for the treatment of degenerative scoliosis: a meta-analysis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2020, 24(3): 438-445. |

| [4] | Zhang Jian, Wang Xiaojian, Qin Dean, Zhao Zhongtao, Liang Qingyuan, An Qijun, Song Jiefu. Risk factors for proximal junctional kyphosis after spinal deformity surgery: a meta-analysis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2020, 24(3): 460-468. |

| [5] | Xu Yangyang, Zhang Kai, Li Zhijun, Zhang Yunfeng, Su Baoke, Wang Xing, Wang Lidong, Wang Yidan, He Yujie, Li Kun, Wang Haiyan, Li Xiaohe. Morphological analysis of optimal selection of lumbar pedicle screws in adolescents aged 12-15 years [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2020, 24(21): 3321-3328. |

| [6] | Qin Haikuo, Luo Shixing. Correlation of cortical bone thickness and X-ray gray value in different planes of proximal femur with brittle fracture of female hip [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2020, 24(18): 2867-2872. |

| [7] | Huang Tianji, Yang Shengdong, Lin Hao, Zhang Chunyang, Deng Zhongqi, Zhong Weiyang, Luo Xiaoji. Mapping knowledge domains of bibliometrics regarding percutaneous vertebroplasty and percutaneous kyphoplasty based on VOSviewer [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2020, 24(15): 2410-2417. |

| [8] | Qu Renfei, Mai Yuying, Chen Xiaowei, Hu Huanying, Chen Guozhi, Li Dongdong, Liao Hongbing. Relationship between lactic acid concentration and osteoclast differentiation of mouse monocytes [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2020, 24(14): 2177-2183. |

| [9] | Liu Yapu, Lin Junyu, Yang Zhou, Wu Xiuhua, Wu Xiaoliang, Zhu Qing’an. Three-dimensional visualization and quantitative analysis of microvessels in rat cervical spinal cord using barium sulfate perfusion combined with micro-CT scanning [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2019, 23(36): 5836-5840. |

| [10] | Gao Yangyang, Che Xianda, Han Pengfei, Liang Bin, Li Pengcui. Clinical efficacy of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty between robotic-assisted and conventional manual methods: a meta-analysis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2019, 23(36): 5889-5895. |

| [11] | Shao Yijie1, Jiang Huaye1, Gao Chao1, Luo Zongping2, Yang Huilin1. Effect of reduction of mechanical loading on subchondral bone and articular cartilage of early osteoarthritis in mice [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2019, 23(35): 5611-5618. |

| [12] | Lian Chao, Zhang Maorong, Wang Junyuan, Cheng Bo, Liu Feng. Relationship between femoral head diameter and edge load under dynamic micro-separation of ceramic hip joints [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2019, 23(32): 5085-5091. |

| [13] | Liu Hongwei, Jiang Junfeng, Zhang Yunkun, Xu Nanwei, Wang Caimei, Zhang Wen. Biomechanical comparison of personalized titanium femoral prosthesis fabricated by three-dimensional printing to four types of cementless prosthesis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2019, 23(32): 5151-5157. |

| [14] | Shi Songyuan1, Peng Zhihui2. Current problems and potential treatment options for sports cartilage injury [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2019, 23(31): 5059-5064. |

| [15] | Yi Guoliang, Wang Shankun, Song Xizheng. Biomechanical testing of the locking axial lumbosacral interbody fusion [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2019, 23(28): 4546-4551. |

| Viewed | ||||||

|

Full text |

|

|||||

|

Abstract |

|

|||||