Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research ›› 2026, Vol. 30 ›› Issue (23): 5897-5905.doi: 10.12307/2026.346

Mitophagy impairment mediated muscular atrophy: insights from the Drosophila model

Li Zijing1, Chen Xuwu2, Ouyang Xinye3, Wang Maoyuan4, 5, 6

- 1School of Basic Medical Sciences, 2School of Rehabilitation, 3The First School of Clinical Medicine, Gannan Medical University, Ganzhou 341000, Jiangxi Province, China; 4First Affiliated Hospital of Gannan Medical University, Ganzhou 341000, Jiangxi Province, China; 5Ganzhou Intelligent Rehabilitation Technological Innovation Center, Ganzhou 341000, Jiangxi Province, China; 6Ganzhou Key Laboratory of Rehabilitation Medicine, Ganzhou 341000, Jiangxi Province, China

-

Received:2025-05-26Accepted:2025-08-29Online:2026-08-18Published:2025-12-30 -

Contact:Wang Maoyuan, MD, Professor, Chief physician, First Affiliated Hospital of Gannan Medical University, Ganzhou 341000, Jiangxi Province, China; Ganzhou Intelligent Rehabilitation Technological Innovation Center, Ganzhou 341000, Jiangxi Province, China; Ganzhou Key Laboratory of Rehabilitation Medicine, Ganzhou 341000, Jiangxi Province, China -

About author:Li Zijing, MS candidate, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Gannan Medical University, Ganzhou 341000, Jiangxi Province, China -

Supported by:Major Project of Ganzhou Science and Technology Bureau, No. 2023LNS37155 (to WMY); National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 82060420 (to WMY)

CLC Number:

Cite this article

Li Zijing, Chen Xuwu, Ouyang Xinye, Wang Maoyuan. Mitophagy impairment mediated muscular atrophy: insights from the Drosophila model[J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(23): 5897-5905.

share this article

Add to citation manager EndNote|Reference Manager|ProCite|BibTeX|RefWorks

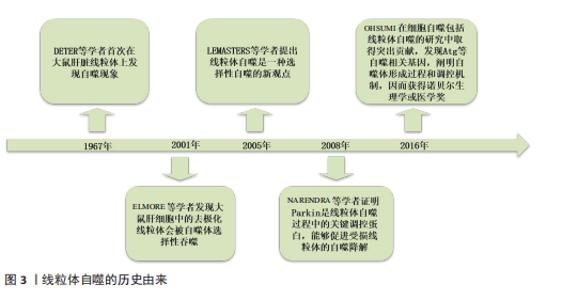

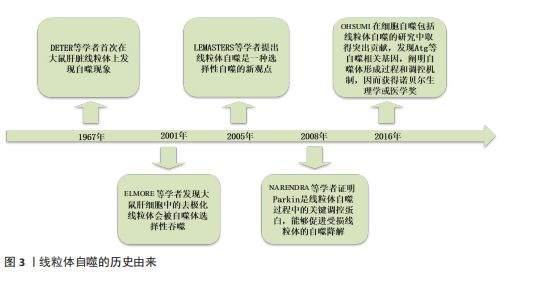

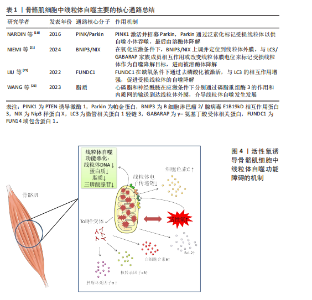

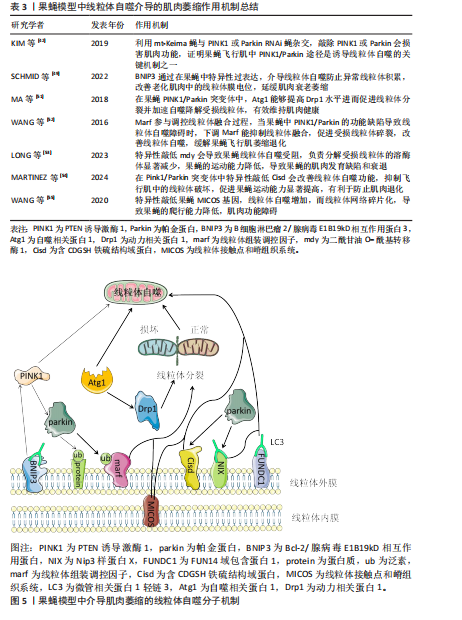

2.1 线粒体自噬概述 2.1.1 线粒体自噬的由来 线粒体是一种通过特异性清除衰老或受损线粒体来维持细胞内稳态的选择性自噬。1967年,DETER等[13]首次在大鼠肝脏线粒体上观察到“自我降解”现象,该过程即被命名为“自噬”。2001年,ELMORE等[14]发现大鼠肝细胞线粒体受损时,会出现线粒体去极化,随后进入自噬体中被选择性吞噬。2005年,LEMASTERS等[15]提出“线粒体自噬”的新概念,认为线粒体自噬是一种选择性自噬过程。而在2008年,这一领域研究取得了突破性进展,科学家发现在敲除自噬相关蛋白5的小鼠胚胎成纤维细胞中,缺乏Parkin会导致机体内线粒体的异常积累,证明了Parkin能够促进受损线粒体的自噬降解[16]。2016年,日本科学家OHSUMI[17]因为在阐明细胞自噬包括线粒体自噬的分子机制和生理功能上做出突出贡献而获得诺贝尔生理学或医学奖,他首次鉴定出与自噬相关的关键基因如自噬相关基因(autophagy-related gene,Atg)等,探索出自噬体的形成过程和调控机制,并且证明了自噬过程与肌肉退行性病变等密切相关,见图3。 2.1.2 骨骼肌细胞中线粒体自噬的核心调控通路 PINK1是一种由PINK1基因编码的丝氨酸/苏氨酸激酶,而Parkin是指存在于骨骼肌细胞胞浆中的一种E3泛素连接酶[18],正常生理情况下PINK1在线粒体靶向序列和线粒体膜电位的作用下会被输入到健康的线粒体中并通过泛素-蛋白酶体系统快速降解。而当线粒体受损(如膜电位下降等)时,PINK1无法进入线粒体内膜,转而聚集在线粒体外膜上,形成二聚体并被磷酸化激活招募大量的Parkin蛋白,Parkin通过泛素化线粒体外膜相关蛋白,标记损伤的线粒体以供自噬体吞噬,继而传递给溶酶体降解[19-20]。 BNIP3/NIX是一类重要的线粒体自噬受体,正常条件下,BNIP3/NIX主要存在于胞质中,少量存在于线粒体[21]。当细胞处于缺氧或者氧化应激的情况下,BNIP3/NIX表达上调,并被定位到线粒体外膜上,能够直接与LC3/γ-氨基丁酸受体相关蛋白(γ-aminobutyric acid receptor-associated protein,GABARAP)家族成员相互作用进而标记该线粒体,也有科学家认为BNIP3/NIX通过改变线粒体膜电位如线粒体去极化,导致线粒体损伤,从而标记该线粒体成为自噬降解的目标,随后形成自噬小体与溶酶体相融合完成降解,此外BNIP3/NIX还能抑制哺乳动物雷帕霉素靶蛋白(mammalian target of rapamycin,mTOR)途径的激活,增强线粒体自噬[22-23]。"

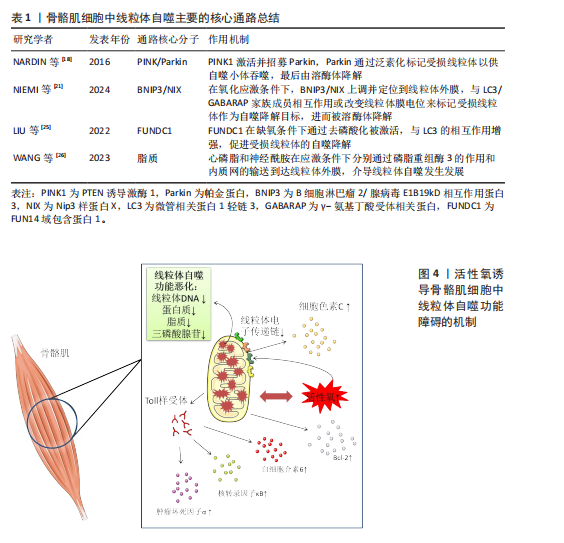

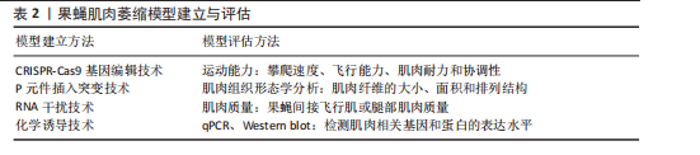

FUNDC1是一种位于线粒体外膜上的线粒体自噬蛋白,在低氧情况下诱导的线粒体自噬中扮演关键角色,当骨骼肌细胞处于正常生理状态下时,FUNDC1由于被磷酸化,与LC3/GABARAP家族成员的结合亲和力显著降低。但是在缺氧或者氧化磷酸化解偶联情况下,FUNDC1的磷酸化水平下降,FUNDC1与LC3之间的相互作用被增强,从而促进受损的线粒体被自噬小体识别和包裹,随后在溶酶体的作用下降解[24-25]。此外,在线粒体上存在一些脂质如心磷脂和神经酰胺,也能够通过它的LC3结合结构域介导线粒体自噬。例如在应激状态下,心磷脂通过磷脂重组酶3的作用从线粒体内膜转移到外膜与LC3-Ⅱ结合并启动自噬。在内质网应激条件下,神经酰胺会从内质网输送到线粒体外膜上为线粒体自噬的开始做准备[26],见表1。 2.1.3 骨骼肌细胞中线粒体自噬的病理机制 线粒体自噬作为骨骼肌细胞内一种重要的质量控制过程,旨在识别和降解损伤的线粒体,以维持细胞内稳态,如果其功能失调,会导致一系列复杂的反应使细胞处于病理状态[27]。线粒体自噬有利于清除细胞内损伤的线粒体,防止线粒体过度积累对细胞造成损害。然而,当自噬的机制出现故障,无法正常识别和处理这些异常的线粒体时,会导致它们在细胞内积聚,这种异常积聚不仅降低了细胞的能量生产效率,还会释放一些有害物质,如活性氧和促凋亡因子,从而对细胞产生进一步损害。线粒体是细胞产生活性氧的主要来源之一。由于线粒体自噬功能障碍导致损伤的线粒体不能被及时清除,使得细胞内的活性氧水平升高,进而引发氧化应激反应。较高水平的活性氧会损害线粒体DNA、蛋白质和脂质等,进一步损伤线粒体[28-29]。此外,细胞内线粒体自噬不足会导致低效的线粒体数量增加,直接降低了三磷酸腺苷的生成效率。由于活性氧水平上升造成线粒体电子传递链复合物损伤,也会影响能量代谢,进一步导致细胞能量的供应不足[30]。线粒体自噬失调后,骨骼肌细胞中的损伤线粒体会释放出细胞色素C以及B细胞淋巴瘤2(B-cell lymphoma 2,Bcl-2)家族蛋白等促凋亡分子,激活细胞内部的凋亡信号通路,进而引起程序性细胞死亡[31]。线粒体自噬失调还会通过释放损伤相关分子模式触发局部乃至全身性的炎症反应,这些分子作为模式识别受体如Toll样受体的配体,能够激活免疫系统,诱导相关炎症因子的分泌如肿瘤坏死因子α、核转录因子κB和白细胞介素6,加重炎症反应,最终导致肌肉萎缩的发生[32],见图4。 2.2 基于果蝇模型探讨线粒体自噬与肌肉萎缩之间的关系 2.2.1 果蝇肌肉萎缩模型的建立与评估 果蝇作为研究肌肉萎缩相关疾病的重要模式生物,它的建模方法多种多样。首先,基因编辑技术如成簇规律间隔短回文重复序列/CRISPR关联蛋白9(CRISPR-Cas9)技术介导的基因敲除[33]、传统的P元件插入突变等手段已经被应用于模拟特定基因缺陷诱导的果蝇肌肉萎缩中[34]。最近一项研究报道科学家利用CRISPR-Cas9基因组编辑技术构建三磷酸腺苷酶家族蛋白3A寡聚化果蝇模型,通过干扰Pink1/Parkin介导的线粒体自噬途径,使得果蝇体内的受损线粒体不能被有效清除,导致肌张力下降,进而发生肌肉萎缩[35]。此外,RNA干扰技术(RNA interference,RNAi)通过小分子RNA介导的特异性抑制目标mRNA的表达,为研究果蝇目的基因功能及其在肌肉萎缩中的作用提供了强有力的支持[36],如有研究者利用RNAi技术构建PINK敲除的果蝇模型,探讨葡萄皮提取物对果蝇间接飞行肌(indirect flight muscle,IFM)的作用,发现葡萄皮提取物能够促进线粒体自噬,进而改善肌肉萎缩退化[37]。化学诱导也是一种常见的果蝇建模方式,使用特定的化学物质如药物等诱导肌肉细胞的损伤和死亡,模仿果蝇机体内由于老化或其他因素导致的肌肉萎缩过程[38]。"

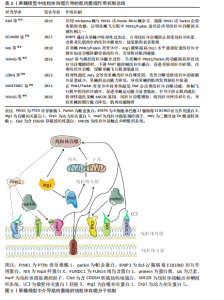

研究者们通常会使用一系列的定量和定性方法对果蝇肌肉表型展开评估,其中运动能力检测是一种常用的方法,包括测量果蝇的攀爬速度、飞行能力、肌肉耐力以及协调性等,可以直接反映肌肉的功能状态[10]。肌肉组织形态学分析则侧重于从微观层面评估肌肉结构的变化,如利用透射电子显微镜观察肌肉纤维的大小、面积、排列结构是否异常。肌肉质量的量化也是评估果蝇肌肉表型的重要指标,目前通过解剖果蝇的间接飞行肌或腿部肌肉进行称质量,但由于果蝇体型微小,技术面临许多挑战[39]。此外,还可以通过分子生物技术如qPCR、Western blot检测肌肉相关基因和蛋白的表达水平探索肌肉萎缩的相关分子机制。综合应用上述评估方法,可以全面地理解果蝇模型肌肉萎缩的特征及其潜在机制,从而为进一步的研究提供坚实的基础[40],见表2。 2.2.2 果蝇模型揭示的线粒体自噬与肌肉萎缩机制 PINK1和Parkin是线粒体自噬机制中的两个关键调控因子,它们之间的相互作用对维持肌肉细胞内线粒体的质量控制至关重要[41]。近年来,科学家们利用线粒体靶向荧光蛋白Keima(mitocondrial Keima,mt-Keima)的转基因小鼠探索了体内线粒体自噬机制,同样的方法被引入到果蝇中,KIM等[42]通过将mt-Keima果蝇与PINK1或Parkin RNAi蝇杂交,证明在缺氧和鱼藤酮处理的条件下,果蝇飞行肌中PINK1/Parkin途径是诱导线粒体自噬、清除损伤线粒体的关键机制之一,因此敲除PINK1或Parkin会损害肌肉功能。在果蝇模型中,PINK1/Parkin 缺失会产生帕金森样表型,如运动缺陷、协调性降低[43]。研究发现PINK1/Parkin突变果蝇模型的间接飞行肌组织学分析显示肌肉完整性严重破坏,肌肉萎缩无力,表明PINK1和Parkin两种调节因子在肌肉萎缩病理过程中扮演着关键的角色[44-45]。这一点在CORNELISSEN等[46]的研究中得到充分的证实,利用表达线粒体自噬探针mt-Keima的果蝇模型,与PINK1"

或Parkin RNAi蝇进行杂交实验,当敲低果蝇中的果蝇泛素特异性蛋白酶15和果蝇泛素特异性蛋白酶30时显著改善了果蝇由于PINK/Parkin缺失导致的线粒体自噬功能障碍,表明PINK1/Parkin途径是至关重要的线粒体自噬机制,并且Parkin 能够代偿部分PINK1的功能丧失,但反之则不然,说明PINK1和Parkin在一条遗传通路中共同发挥作用,而且Parkin作用在PINK1的下游通路,两者可以协同作用通过线粒体自噬促进肌细胞中损伤的线粒体被降解吸收,进而改善肌肉萎缩症状[47]。在果蝇体外实验中PINK1通过磷酸化过程激活Parkin,使其从细胞质迁移到受损的线粒体表面,在线粒体外膜Parkin介导多种蛋白的泛素化,从而标记损伤的线粒体作为自噬降解目标。而在体内实验中,成熟的果蝇运动神经元表现出PINK1/Parkin依赖性的线粒体自噬现象很少。这种反差恰恰说明,在果蝇体内线粒体的质量控制过程不仅仅依赖于PINK1/Parkin介导的自噬,还涉及到其他尚未探索的调控机制[48]。 果蝇模型中除了PINK1/Parkin通路之外,一些其他与线粒体自噬相关的基因得到了广泛深入的研究。如BNIP3作为一种促凋亡蛋白被发现也能够介导线粒体自噬来改善果蝇体内的线粒体稳态,进而保护肌肉。在成年果蝇模型的神经系统中,通过特异性地诱导BNIP3过表达可以增强线粒体自噬,进而防止异常线粒体积累,并且BNIP3的上调显著改善了老化肌肉中受损的线粒体膜电位,有效延缓肌肉衰老萎缩的进程。此外还发现BNIP3能够延长果蝇的寿命,但其中需要自噬激酶Atg1的存在,进一步证实了BNIP3通过调控线粒体自噬实现相关生物学效应[49]。还有研究发现BNIP3通过与PINK1的相互作用抑制其被蛋白酶体切割,导致PINK1的全长形式在线粒体外膜上积聚,从而促进了Parkin向损伤线粒体的募集,使得Parkin更加有效地定位到相关损伤线粒体上,说明BNIP3对于PINK1/Parkin介导的线粒体自噬过程有促进作用。除此之外,在PINK1缺陷型果蝇的间接飞行肌中,BNIP3能够显著提升ATP水平,表明BNIP3可以在体内代偿由于PINK1缺乏导致的线粒体自噬功能异常,改善飞行肌萎缩退化[50]。上述提到的Atg1是一种高度保守的丝氨酸/苏氨酸激酶,在线粒体自噬过程中起着至关重要的作用。研究发现在果蝇PINK1和Parkin突变体中,通过Atg1过表达可以促进线粒体分裂并加速自噬降解受损的线粒体,从而减缓果蝇的肌肉萎缩退化。通过进一步研究表明Atg1能够提高动力相关蛋白1(dynamin-related protein 1,Drp1)蛋白活性并且增加Drp1蛋白水平,从而帮助“坏”的线粒体被分隔出来,促进线粒体质量控制,分担了线粒体自噬机制的压力,从而有效维持肌肉健康[51]。 线粒体组装调控因子(mitochondrial assembly regulatory factor,Marf)作为哺乳动物中线粒体融合蛋白1和线粒体融合蛋白2在果蝇中的同源物,参与调控线粒体的融合过程,如果在果蝇模型中PINK1/Parkin功能缺陷导致线粒体自噬障碍,可以通过下调相关的线粒体重塑因子来代偿,如Marf,过表达Drp1同样能够挽救,这种机制的目的可能是促进受损线粒体的碎裂,从而有利于后续的线粒体自噬过程,缓解成年果蝇的飞行肌萎缩退化[52]。此外还有二酰甘油 O-酰基转移酶 1(diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase 1,mdy)、含CDGSH铁硫结构域蛋白(CDGSH iron sulfur domain-containing protein,Cisd)等,mdy在线粒体质量控制过程中有重要作用,特别是线粒体自噬。研究表明在果蝇中特异性地敲低mdy会导致神经元中的线粒体自噬受损,尤其是负责降解受损线粒体的溶酶体显著减少,果蝇的运动能力降低(如攀爬能力等),间接说明mdy可能导致果蝇的肌肉发育缺陷和衰退[53]。与mdy相似, Cisd是一种位于果蝇内质网膜上的蛋白,是人类CDGSH铁硫结构域蛋白1和CDGSH铁硫结构域蛋白2相对应的同源物,在Pink1/Parkin突变体中Cisd的过度积累导致线粒体自噬流被阻断,通过RNA干扰技术敲低Cisd观察到果蝇的运动能力显著提高,并抑制飞行肌中的线粒体破坏,上调了线粒体自噬功能,有利于防止果蝇的肌肉退化。有趣的是,这种机制并不是通过上调 Pink1介导的磷酸化泛素(phosphorylated ubiquitin,pUb)或者Parkin表达的间接转录影响的,而是Cisd独立特有的[54]。 在上述基因的机制探索中发现果蝇中线粒体自噬功能障碍往往会出现肌肉萎缩退化并且功能受损,然而在线粒体接触点和嵴组织系统(mitochondrial contact site and cristae organizing system,MICOS)中并不是这样,MICOS是一种复杂的多蛋白复合体,在维持线粒体内膜形态和相关功能方面发挥重要作用。研究发现MICOS基因敲低的果蝇爬行能力降低,线粒体形态学发生改变,线粒体网络碎片化,体积缩小,影响细胞的能量代谢,说明果蝇发生肌肉功能障碍,而线粒体自噬却增加,原因可能是为了降解高度解偶联的线粒体,以防止细胞过度死亡并维持肌肉组织完整性[55],相关研究成果见表3。在果蝇中,这些基因的异常表达会破坏线粒体网络的完整性,导致能量代谢过程障碍以及活性氧生成增加,进而加速肌肉萎缩进程,为理解肌肉萎缩的分子机制提供了新的视角,见图5。 2.3 果蝇模型在药物筛选和干预策略中的应用 果蝇作为一种成本低廉、易于遗传操作且效益高的模式生物,在药物筛选和干预策略的研究中展现"

出巨大潜力[56]。相对于其他模式生物如秀丽隐杆线虫,果蝇模型中约有75%的人类疾病相关基因的功能同源物[57],而在秀丽隐杆线虫中较少,甚至有些家族没有功能同源物[58],研究使用的模式生物功能同源物越多越有利于进行大规模遗传筛选,并且果蝇生命周期短暂、繁殖能力强大,可以快速鉴定出对线粒体自噬与肌肉有效的化合物。近来研究报道科学家利用果蝇模型对强直性肌营养不良2型(myotonic atrophy type 2,DM2)进行了大规模药物筛选,最终识别出了4种抑制转化生长因子β相关通路的化合物,这些化合物能有效缓解DM2果蝇模型的间接飞行肌萎缩退化现象[59]。目前基于果蝇模型的高通量小分子药物筛选技术作为一种新兴的强大工具,显著提高了寻找针对特定分子靶点的小分子抑制剂或激动剂的效率[60],有研究报道通过药物靶向途径过表达核因子E2相关因子2增强线粒体自噬,逆转因敲低PINK/Parkin导致的肌肉萎缩进程[61]。因此,果蝇模型的应用为开发有效的肌肉萎缩治疗策略提供了新方向。 2.4 当前研究面对的挑战 2.4.1 果蝇模型研究成果与人类临床应用的转化问题 尽管果蝇模型在遗传学和分子生物学相关研究中发挥了至关重要的作用,但其与哺乳动物模型之间仍存在显著差异[62],例如,解剖结构上果蝇不具备哺乳动物的血管系统、适应性免疫系统等;在基因表达调控方面,线粒体自噬调控肌肉萎缩的机制有所不同,如在果蝇和哺乳动物中PINK1/Parkin通路虽然都参与线粒体自噬的调节,但具体某些信号传导机制和下游效应存在差异。对于肌肉萎缩的建模,只能模拟肌肉萎缩的某些方面,果蝇模型缺少适应性免疫系统,而哺乳动物存在免疫相关因子对肌肉组织中的线粒体自噬过程产生干扰。在药物研发方面,需要谨慎考虑的关键影响因素是小分子的药代动力学和药效学可能不同,使得哺乳动物和果蝇之间药物水平和组织分布曲线存在显著差异[58]。最后,在社会伦理学方面,人类临床研究不可避免地需要更加严格的安全性和有效性评估标准。综上所述,即使果蝇模型在肌肉萎缩的研究中具有巨大优势,但其得出的研究结果转化为临床应用仍面临重重挑战。 2.4.2 缺乏系统性研究线粒体自噬在肌肉萎缩中的作用 虽然目前研究表明线粒体自噬与肌肉萎缩之间存在联系,但大多数研究聚焦于特定基因或信号通路的作用,从而缺乏对整个过程的综合全面和系统直观的理解。例如,尽管PINK1/Parkin通路、BNIP3等在线粒体自噬中扮演着重要角色,但是目前对于这些生物分子之间的相互作用与联系以及它们如何具体影响肌肉功能的了解还不够深入[26]。除此之外,不同环境因素及本身的遗传因素如何影响线粒体自噬在肌肉萎缩中的作用机制仍不清楚。因此,需要更加综合的研究,从分子水平到组织水平,最后再到机体生理状态的变化。 2.5 未来研究方向 虽然一些线粒体自噬关键调控因子已被发现,但这一复杂的调节网络还远未被完全揭示,未来研究应致力于利用果蝇模型探索未知的线粒体自噬调控因子,尤其是存在于神经和肌肉组织中的特异性因子[63]。果蝇作为理想的高通量筛选模型,可以开发基于果蝇模型的高通量筛选平台,用于筛选新的调控线粒体自噬机制的小分子化合物或基因靶点[60]。其次,结合当前先进的成像技术和多组学方法系统地监测与线粒体自噬相关分子标志物的动态变化[64],也可以通过构建特定报告基因系统,如荧光物质标记的线粒体自噬相关蛋白,直接观察果蝇线粒体自噬活性的变化,深入探讨线粒体自噬与肌肉萎缩之间的联系[65]。从转化医学未来的视角上看,必须把果蝇模型的研究成果应用于哺乳动物模型,进而扩展到临床研究。而果蝇在基础生物医学研究方面具有显著优势,如何将果蝇模型中的重大发现应用到哺乳动物乃至人类的疾病防治,这是未来的研究方向之一[66]。此外,利用基因工程疗法来修复或代偿诱发线粒体自噬功能障碍的相关缺陷基因,如纠正突变的PINK1或Parkin基因序列,从而达到改善线粒体自噬障碍的目的[67]。除了以上直接作用于线粒体自噬途径外,还可以利用其他相关信号通路间接影响线粒体自噬,如mTOR介导的信号通路能够参与线粒体再循环,提高线粒体肌病中的线粒体自噬水平,进而促进肌肉生长发育[68]。"

| [1] BILGIC SN, DOMANIKU A, TOLEDO B, et al. EDA2R-NIK signalling promotes muscle atrophy linked to cancer cachexia. Nature. 2023;617(7962):827-834. [2] YIN L, LI N, JIA W, et al. Skeletal muscle atrophy: From mechanisms to treatments. Pharmacol Res. 2021;172:105807. [3] ANDRIEUX P, CHEVILLARD C, CUNHA-NETO E, et al. Mitochondria as a Cellular Hub in Infection and Inflammation. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(21):11338. [4] BELLANTI F, LO BUGLIO A, VENDEMIALE G. Muscle Delivery of Mitochondria-Targeted Drugs for the Treatment of Sarcopenia: Rationale and Perspectives. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(12):2588. [5] 李伟,尹洪涛,孙永晨,等.线粒体移植治疗肌少症的潜力[J].中国组织工程研究,2025,29(13):2842-2848. [6] LEDUC-GAUDET JP, HUSSAIN SNA, BARREIRO E, et al. Mitochondrial Dynamics and Mitophagy in Skeletal Muscle Health and Aging. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(15):8179. [7] SULKSHANE P, RAM J, THAKUR A, et al. Ubiquitination and receptor-mediated mitophagy converge to eliminate oxidation-damaged mitochondria during hypoxia. Redox Biol. 2021;45:102047. [8] IMBERECHTS D, KINNART I, WAUTERS F, et al. DJ-1 is an essential downstream mediator in PINK1/parkin-dependent mitophagy. Brain. 2022;145(12):4368-4384. [9] WANG H, LUO W, CHEN H, et al. Mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy: Molecular structure, orchestrating mechanism and related disorders. Mitochondrion. 2024;75:101847. [10] CHRISTIAN CJ, BENIAN GM. Animal models of sarcopenia. Aging Cell. 2020;19(10): e13223. [11] PIPER MDW, PARTRIDGE L. Drosophila as a model for ageing. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2018;1864(9 Pt A):2707-2717. [12] DEMONTIS F, PICCIRILLO R, GOLDBERG AL, et al. Mechanisms of skeletal muscle aging: insights from Drosophila and mammalian models. Dis Model Mech. 2013;6(6):1339-1352. [13] DETER RL, DE DUVE C. Influence of glucagon, an inducer of cellular autophagy, on some physical properties of rat liver lysosomes. J Cell Biol. 1967;33(2):437-449. [14] ELMORE SP, QIAN T, GRISSOM SF, et al. The mitochondrial permeability transition initiates autophagy in rat hepatocytes. FASEB J. 2001;15(12):2286-2287. [15] LEMASTERS JJ. Selective mitophagy, or mitophagy, as a targeted defense against oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and aging. Rejuvenation Res. 2005;8(1):3-5. [16] NARENDRA D, TANAKA A, SUEN DF, et al. Parkin is recruited selectively to impaired mitochondria and promotes their autophagy. J Cell Biol. 2008;183(5):795-803. [17] OHSUMI Y. Historical landmarks of autophagy research. Cell Res. 2014;24(1):9-23. [18] NARDIN A, SCHREPFER E, ZIVIANI E. Counteracting PINK/Parkin Deficiency in the Activation of Mitophagy: A Potential Therapeutic Intervention for Parkinson’s Disease. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2016;14(3):250-259. [19] LI A, GAO M, LIU B, et al. mitophagy: molecular mechanisms and implications for cardiovascular disease. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13(5):444. [20] LI J, YANG D, LI Z, et al. PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy in neurodegenerative diseases. Ageing Res Rev. 2023;84:101817. [21] NIEMI NM, FRIEDMAN JR. Coordinating BNIP3/NIX-mediated mitophagy in space and time. Biochem Soc Trans. 2024;52(5): 1969-1979. [22] ADRIAENSSENS E, SCHAAR S, COOK ASI, et al. Reconstitution of BNIP3/NIX-mediated autophagy reveals two pathways and hierarchical flexibility of the initiation machinery. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2024:2024.08.28.609967. [23] SUN Y, CAO Y, WAN H, et al. A mitophagy sensor PPTC7 controls BNIP3 and NIX degradation to regulate mitochondrial mass. Mol Cell. 2024;84(2):327-344.e9. [24] CHEN M, CHEN Z, WANG Y, et al. Mitophagy receptor FUNDC1 regulates mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy. Autophagy. 2016;12(4):689-702. [25] LIU H, ZANG C, YUAN F, et al. The role of FUNDC1 in mitophagy, mitochondrial dynamics and human diseases. Biochem Pharmacol. 2022;197:114891. [26] WANG S, LONG H, HOU L, et al. The mitophagy pathway and its implications in human diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):304. [27] WANG R, WANG G. Autophagy in Mitochondrial Quality Control. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1206:421-434. [28] LU Y, LI Z, ZHANG S, et al. Cellular mitophagy: Mechanism, roles in diseases and small molecule pharmacological regulation. Theranostics. 2023;13(2):736-766. [29] SU L, ZHANG J, GOMEZ H, et al. Mitochondria ROS and mitophagy in acute kidney injury. Autophagy. 2023;19(2):401-414. [30] NOLFI-DONEGAN D, BRAGANZA A, SHIVA S. Mitochondrial electron transport chain: Oxidative phosphorylation, oxidant production, and methods of measurement. Redox Biol. 2020;37:101674. [31] WANDEROY S, HEES JT, KLESSE R, et al. Kill one or kill the many: interplay between mitophagy and apoptosis. Biol Chem. 2020;402(1):73-88. [32] SLITER DA, MARTINEZ J, HAO L, et al. Parkin and PINK1 mitigate STING-induced inflammation. Nature. 2018;561(7722): 258-262. [33] NYBERG KG, CARTHEW RW. CRISPR-/Cas9-Mediated Precise and Efficient Genome Editing in Drosophila. Methods Mol Biol. 2022;2540:135-156. [34] ZHANG S, POINTER B, KELLEHER ES. Rapid evolution of piRNA-mediated silencing of an invading transposable element was driven by abundant de novo mutations. Genome Res. 2020;30(4):566-575. [35] YAP ZY, PARK YH, WORTMANN SB, et al. Functional interpretation of ATAD3A variants in neuro-mitochondrial phenotypes. Genome Med. 2021;13(1):55. [36] KARUNENDIRAN A, NGUYEN CT, BARZDA V, et al. Disruption of Drosophila larval muscle structure and function by UNC45 knockdown. BMC Mol Cell Biol. 2021; 22(1):38. [37] WU Z, WU A, DONG J, et al. Grape skin extract improves muscle function and extends lifespan of a Drosophila model of Parkinson’s disease through activation of mitophagy. Exp Gerontol. 2018;113:10-17. [38] BHATTACHARYA MRC. A Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy Model in Drosophila melanogaster. Methods Mol Biol. 2020;2143:301-310. [39] CHECHENOVA M, STRATTON H, KIANI K, et al. Quantitative model of aging-related muscle degeneration: a Drosophila study. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2023:2023.02.19.529145. [40] KOMLÓS M, SZINYÁKOVICS J, FALCSIK G, et al. The Small-Molecule Enhancers of Autophagy AUTEN-67 and -99 Delay Ageing in Drosophila Striated Muscle Cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(9):8100. [41] REN Y, WANG K, WU Y, et al. Lycium barbarum polysaccharide mitigates high-fat-diet-induced skeletal muscle atrophy by promoting AMPK/PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy. Int J Biol Macromol. 2025;301:140488. [42] KIM YY, UM JH, YOON JH, et al. Assessment of mitophagy in mt-Keima Drosophila revealed an essential role of the PINK1-Parkin pathway in mitophagy induction in vivo. FASEB J. 2019;33(9):9742-9751. [43] BERNARDO G, PRADO MA, DASHTMIAN AR, et al. USP14 inhibition enhances Parkin-independent mitophagy in iNeurons. Pharmacol Res. 2024;210:107484. [44] PARK J, LEE SB, LEE S, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Drosophila PINK1 mutants is complemented by parkin. Nature. 2006;441(7097):1157-1161. [45] GREENE JC, WHITWORTH AJ, KUO I, et al. Mitochondrial pathology and apoptotic muscle degeneration in Drosophila parkin mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(7):4078-4083. [46] CORNELISSEN T, VILAIN S, VINTS K, et al. Deficiency of parkin and PINK1 impairs age-dependent mitophagy in Drosophila. Elife. 2018;7:e35878. [47] VOIGT A, BERLEMANN LA, WINKLHOFER KF. The mitochondrial kinase PINK1: functions beyond mitophagy. J Neurochem. 2016;139 Suppl 1:232-239. [48] SUNG H, TANDARICH LC, NGUYEN K, et al. Compartmentalized Regulation of Parkin-Mediated Mitochondrial Quality Control in the Drosophila Nervous System In Vivo. J Neurosci. 2016;36(28):7375-7391. [49] SCHMID ET, PYO JH, WALKER DW. Neuronal induction of BNIP3-mediated mitophagy slows systemic aging in Drosophila. Nat Aging. 2022;2(6):494-507. [50] ZHANG T, XUE L, LI L, et al. BNIP3 Protein Suppresses PINK1 Kinase Proteolytic Cleavage to Promote Mitophagy. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(41):21616-21629. [51] MA P, YUN J, DENG H, et al. Atg1-mediated autophagy suppresses tissue degeneration in pink1/parkin mutants by promoting mitochondrial fission in Drosophila. Mol Biol Cell. 2018;29(26):3082-3092. [52] WANG ZH, CLARK C, GEISBRECHT ER. Drosophila clueless is involved in Parkin-dependent mitophagy by promoting VCP-mediated Marf degradation. Hum Mol Genet. 2016;25(10):1946-1964. [53] LONG M, MCWILLIAMS TG. Lipid droplets promote efficient mitophagy. Autophagy. 2023;19(2):724-725. [54] MARTINEZ A, SANCHEZ-MARTINEZ A, PICKERING JT, et al. Mitochondrial CISD1/Cisd accumulation blocks mitophagy and genetic or pharmacological inhibition rescues neurodegenerative phenotypes in Pink1/parkin models. Mol Neurodegener. 2024;19(1):12. [55] WANG LJ, HSU T, LIN HL, et al. Drosophila MICOS knockdown impairs mitochondrial structure and function and promotes mitophagy in muscle tissue. Biol Open. 2020;9(12):bio054262. [56] DAMSCHRODER D, RICHARDSON K, COBB T, et al. The effects of genetic background on exercise performance in Drosophila. Fly (Austin). 2020;14(1-4):80-92. [57] MUNNIK C, XABA MP, MALINDISA ST, et al. Drosophila melanogaster: A platform for anticancer drug discovery and personalized therapies. Front Genet. 2022;13:949241. [58] PANDEY UB, NICHOLS CD. Human disease models in Drosophila melanogaster and the role of the fly in therapeutic drug discovery. Pharmacol Rev. 2011;63(2):411-436. [59] DENG J, GUAN XX, ZHU YB, et al. Reducing the Excess Activin Signaling Rescues Muscle Degeneration in Myotonic atrophy Type 2 Drosophila Model. J Pers Med. 2022;12(3):385. [60] ZHANG Z, WANG Y, ZHAO J, et al. High-Throughput Small Molecule Drug Screening For Age-Related Sleep Disorders Using Drosophila melanogaster. J Vis Exp. 2023; (200). doi: 10.3791/65787. [61] GUMENI S, PAPANAGNOU ED, MANOLA MS, et al. Nrf2 activation induces mitophagy and reverses Parkin/Pink1 knock down-mediated neuronal and muscle degeneration phenotypes. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12(7):671. [62] GRAHAM P, PICK L. Drosophila as a Model for Diabetes and Diseases of Insulin Resistance. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2017;121: 397-419. [63] 杨天爱,夏志,张舵,等.运动经线粒体自噬途径改善衰老性骨骼肌萎缩研究进展[J].中国运动医学杂志,2024,43(10): 835-843. [64] MAYNERIS-PERXACHS J, CASTELLS-NOBAU A, ARNORIAGA-RODRÍGUEZ M, et al. Microbiota alterations in proline metabolism impact depression. Cell Metab. 2022;34(5):681-701.e10. [65] MATHER LM, CHOLAK ME, MORFOOT CM, et al. Inducible Reporter Lines for Tissue-specific Monitoring of Drosophila Circadian Clock Transcriptional Activity. J Biol Rhythms. 2023;38(1):44-63. [66] LI L, WAZIR J, HUANG Z, et al. A comprehensive review of animal models for cancer cachexia: Implications for translational research. Genes Dis. 2023; 11(6):101080. [67] XUE J, LI G, JI X, et al. Drosophila ZIP13 over-expression or transferrin1 RNAi influences the muscle degeneration of Pink1 RNAi by elevating iron levels in mitochondria. J Neurochem. 2022;160(5):540-555. [68] SU Y, WANG T, WU N, et al. Alpha-ketoglutarate extends Drosophila lifespan by inhibiting mTOR and activating AMPK. Aging (Albany NY). 2019;11(12):4183-4197. |

| [1] | Gao Zengjie, , Pu Xiang, Li Lailai, Chai Yihui, Huang Hua, Qin Yu. Increased risk of osteoporotic pathological fractures associated with sterol esters: evidence from IEU-GWAS and FinnGen databases [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(5): 1302-1310. |

| [2] | Zhou Fada, Long Zhisheng. Roles and mechanisms of mitochondrial dynamics in bone defect repair [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(23): 5906-5914. |

| [3] | Gao Jiabin, Li Tianqi, Xu Kun, Zhu Hanmin, Zhou Xi, Li Wei. Mitophagy regulates osteoclasts: a new perspective for osteoporosis treatment [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(23): 5982-5991. |

| [4] | Yang Zijiang, Guo Chenggen, Deng Ziao, Xue Xinxuan. Postbiotic targeting muscle aging: mechanistic insights and application prospects of urolithin A [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(22): 5804-5813. |

| [5] | Ji Long, Gong Guopan, Kong Xiangkui, Jin Pan, Chen Ziyang, Pu Rui. The role of exercise-regulated mitophagy in cardiovascular diseases [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(22): 5832-5843. |

| [6] | Han Jie, Hu Tianfa, Wu Yachao, Nong Bin, Yu Kailong. Forkhead box transcription factor O3 affects bone metabolism and participates in the pathological processes of various bone-related diseases [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(22): 5770-5781. |

| [7] | Wang Siwei, Yao Xiaosheng, Qi Xiaonan, Wang Yu, Cui Haijian, Zhao Jiaxuan. Matrix metalloproteinase 9 mediates mitophagy to regulate osteogenesis and myogenesis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(18): 4557-4567. |

| [8] | Zhang Shuli, Hou Chaowen, Yuan Shanshan, Ma Yuhua . Mechanism by which exercise regulates autophagy in different physiological systems [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(18): 4737-4748. |

| [9] | Huang Sijing, Cui Rui, Geng Longyu, Gao Beiyao, Ge Ruidong, Jiang Shan. Application and molecular mechanism of extracorporeal shock wave for anti-fibrosis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(17): 4417-4429. |

| [10] | Ji Kaizhong, Kong Yihao, Zhi Yiqing, Jin Yingying, Chen Jianquan. Effects and mechanisms of palmitoyl acyltransferase ZDHHC5 in tissue homeostasis and diseases [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(17): 4430-4445. |

| [11] | Yu Le, Nan Songhua, Shi Zijian, He Qiqi, Li Zhenjia, Cui Yinglin. Mechanisms underlying mitophagy, ferroptosis, cuproptosis, and disulfidptosis in Parkinson’s disease [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(17): 4446-4456. |

| [12] | Mao Sujie, Gao Jie, Pan Zhuangli. Immune cells synergistically regulate inflammatory response, muscle regeneration and metabolic homeostasis in training-induced stress responses [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(10): 2671-2680. |

| [13] | Chen Qiheng, Weng Tujun, Peng Jiang. Effect of dimethylglyoxal glycine on osteogenic, adipogenesis differentiation, and mitophagy of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(1): 50-57. |

| [14] | Li Jiagen, Chen Yueping, Huang Keqi, Chen Shangtong, Huang Chuanhong. The construction and validation of a prediction model based on multiple machine learning algorithms and the immunomodulatory analysis of rheumatoid arthritis from the perspective of mitophagy [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2025, 29(在线): 1-15. |

| [15] | Li Jialin, Zhang Yaodong, Lou Yanru, Yu Yang, Yang Rui. Molecular mechanisms underlying role of mesenchymal stem cell secretome [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2025, 29(7): 1512-1522. |

| Viewed | ||||||

|

Full text |

|

|||||

|

Abstract |

|

|||||