Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research ›› 2026, Vol. 30 ›› Issue (11): 2846-2857.doi: 10.12307/2026.109

Previous Articles Next Articles

Pathogenesis of diabetic periodontitis and its local drug delivery treatment strategies

Yang Xirui, He Jinfeng

- School of Stomatology, Jinan University, Guangzhou 510632, Guangdong Province, China

-

Received:2025-05-20Accepted:2025-06-07Online:2026-04-18Published:2025-09-06 -

Contact:He Jinfeng, PhD, Lecturer, School of Stomatology, Jinan University, Guangzhou 510632, Guangdong Province, China -

About author:Yang Xirui, School of Stomatology, Jinan University, Guangzhou 510632, Guangdong Province, China -

Supported by:The Open Project of Engineering Research Center of Artificial Organs and Materials, Ministry of Education, No. ERCAOM202402 (to HJF)

CLC Number:

Cite this article

Yang Xirui, He Jinfeng. Pathogenesis of diabetic periodontitis and its local drug delivery treatment strategies[J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(11): 2846-2857.

share this article

Add to citation manager EndNote|Reference Manager|ProCite|BibTeX|RefWorks

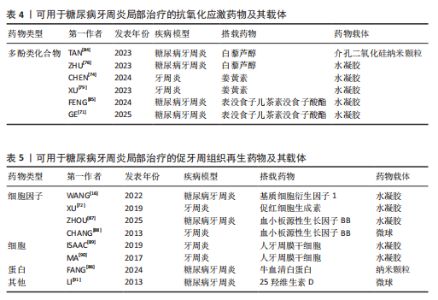

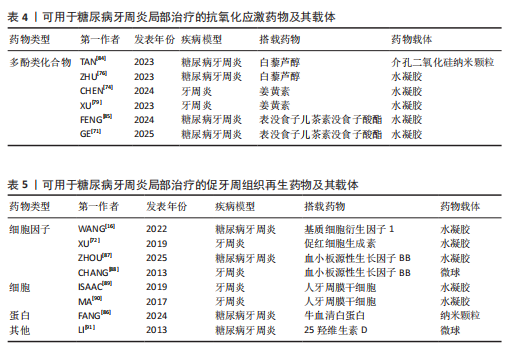

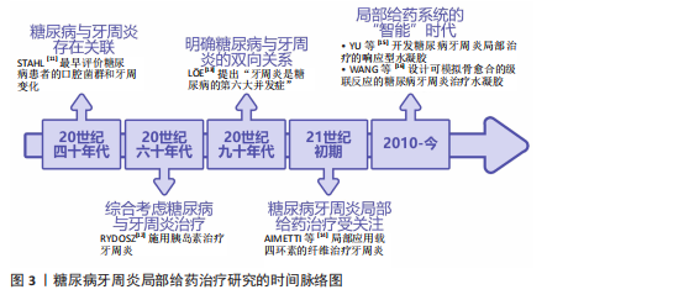

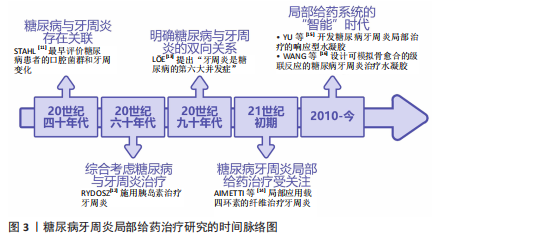

2.1 糖尿病牙周炎局部给药治疗研究的时间脉络 早在20世纪40年代,便有学者注意到了糖尿病与牙周炎间存在影响关系。STAHL[11]最早评价了糖尿病患者的口腔菌群变化和X射线下的牙周变化,发现牙槽骨的吸收程度与糖尿病严重程度有关。此后,学者们逐渐从孤立地看待糖尿病与牙周炎转向综合考虑二者进行治疗。1967年,RYDOSZ[12]在牙周局部施用胰岛素以治疗牙周炎。学者们不断深化对糖尿病与牙周炎双向关系的研究,20世纪90年代,就有有学者提出“牙周炎是糖尿病的第六大并发症”[13]。进入21世纪,随着对糖尿病牙周炎认识的深入,糖尿病牙周炎的局部给药治疗也逐渐受到关注。2004年,AIMETTI等[14]局部应用载有四环素的纤维治疗牙周炎。2010年至今,各种局部给药系统蓬勃发展,进入“智能”时代。智能响应性水凝胶等局部药物递送系统在糖尿病牙周炎的治疗中各放异彩,例如,2016年,XIAO等[15]将葡萄糖响应型水凝胶应用于糖尿病牙周炎的局部治疗;2023年,WANG等[16]设计的水凝胶已能够模拟自然骨愈合的级联反应治疗糖尿病牙周炎。糖尿病牙周炎局部给药治疗的研究时间脉络,见图3。 2.2 糖尿病牙周炎的发病机制 2.2.1 牙周炎的主要致病因素与发病机制 牙周炎发病的始动因素是牙菌斑生物膜,细菌凭借生物膜结构紧密黏附在一起生长,是造成牙周组织破坏的重要因素。人类口腔中存在1 000多种细菌,正常情况下,这些常驻于口腔的菌群与人体免疫系统之"

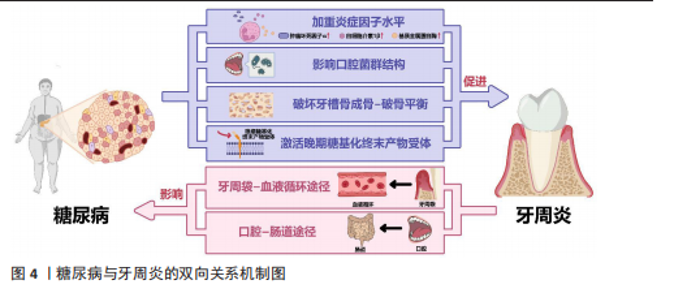

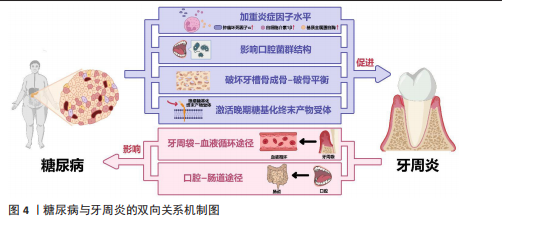

间保持着动态平衡[17]。但当这种动态平衡失调,宿主-微生物的共生关系会逐渐转变为致病关系,一些病原微生物可通过直接破坏牙周组织,或分泌大量毒力因子诱导炎症、参与牙菌斑生物膜的形成和进一步加重口腔微生物菌群失调等间接破坏牙周组 织[18]。牙周炎与牙龈卟啉单胞菌、放线聚集杆菌、连翘坦纳菌等细菌密切相关[19]。定植于牙体、口腔软组织上的牙菌斑生物膜内的细菌及其代谢产物会直接破坏结合上皮,为进一步侵入牙周组织开辟通道,进而破坏牙周组织中的胶原与基质成分,引起牙周组织的变性和降解,形成并加深牙周袋,加重骨吸收[18]。同时,细菌及其代谢产物还可激活宿主防御反应,产生白细胞介素1、白细胞介素6、白细胞介素8、肿瘤坏死因子α、前列腺素E2、基质金属蛋白酶等促炎细胞因子,进一步导致牙周组织继发性损伤[18]。 人体免疫反应的失衡是牙周炎发病的重要因素。在细菌抗原成分刺激和细胞因子的调节下,多种免疫细胞也被激活并参与牙周炎的病理反应。其中,中性粒细胞是人体抵御病原微生物的第一道防线,其稳态也是牙周健康的关键所在[20]。据报道,牙周炎是一种以中性粒细胞为中心的疾病,牙周组织损伤程度与局部中性粒细胞的功能高度相关[21]。成熟的中性粒细胞可通过黏附和趋化等一系列活动穿过血管内皮到达炎症部位吞噬细菌,释放溶酶体酶,在趋化因子CXC基序趋化因子配体8/CXC趋化因子受体1信号轴的作用下激活呼吸爆发途径,产生大量活性氧和一氧化氮,从而杀灭抗原和细菌[18]。然而,在牙周炎患者中,早期中性粒细胞的募集、迁移和浸润增加,而吞噬功能却显著降低[22]。中性粒细胞产生的过量活性氧、一氧化氮也会导致局部细胞的氧化应激,从而进一步加剧牙支持组织的破坏[23]。除了中性粒细胞,巨噬细胞、T细胞等多种免疫细胞也参与了牙周炎的病理反应,例如,牙周炎局部微生物平衡失调引起的细胞因子水平变化可驱动巨噬细胞向M1表型分化,释放多种促炎因子增强炎症反应[24];辅助性T细胞1和辅助性T细胞2免疫反应之间的平衡也可参与牙周炎活动期和静止期之间的转变[25]。总之,人体免疫环境调节的失衡以及局部免疫细胞功能障碍或过度激活,都会导致牙周炎的进展和组织破坏。 人体的易感性也是牙周炎发病的决定性因素之一,遗传因素、吸烟、饮酒、口腔卫生习惯不良等多种危险因素均可增加人体对牙周炎的易感性[26]。多种全身性系统疾病也可增加人体的牙周炎易感性,如糖尿病、肥胖、艾滋病、克罗恩病和溃疡性结肠炎等[6,26-27]。 2.2.2 糖尿病与牙周炎的双向关系 糖尿病可通过加重牙周组织炎症因子水平、影响口腔菌群结构、破坏牙槽骨成骨-破骨平衡、激活晚期糖基化终末产物受体加重牙周炎的发病风险和患病程度;而牙周炎可通过牙周袋-血液循环途径、口腔-肠道途径影响胰岛B细胞、肝细胞、脂肪细胞等细胞功能,进而影响糖尿病及其并发症,见图4。 (1)糖尿病加重牙周炎风险和程度:糖尿病可影响免疫细胞功能,提高牙周组织炎症因子和氧化应激水平。糖尿病患者的中性粒细胞等多形核白细胞存在活性缺陷,这些细胞的趋化性、吞噬功能、杀灭病原微生物等功能受损,导致其在牙周组织中的滞留时间延长,使细菌在牙周袋中长期定殖[28]。糖尿病患者的多形核白细胞反应性也会明显增高,较低水平的刺激便可激活局部免疫和炎症反应,导致肿瘤坏死因子α、白细胞介素1β、活性氧、基质金属蛋白酶等细胞因子的大量产生,进而破坏牙周组织[18,29]。 除多形核白细胞外,糖尿病还能通过调节树突状细胞、促进辅助性T细胞1/辅助性T细胞17淋巴细胞的生成、抑制调节性T细胞的形成来影响牙周骨质流失。辅助性T 细胞1和辅助性T 细胞17是核因子κB受体活化因子配体和白细胞介素17等细胞因子的来源,而这些细胞因子在糖尿病牙周炎患者中明显升高[30]。骨保护素、核因子κB受体活化因子及其配体等细胞因子维持着骨吸收与形成的动态平衡,而糖尿病牙周炎患者体内的骨保护素-核因子κB受体活化因子及其配体系统失调。有研究发现,糖尿病牙周炎患者血清内的骨保护素"

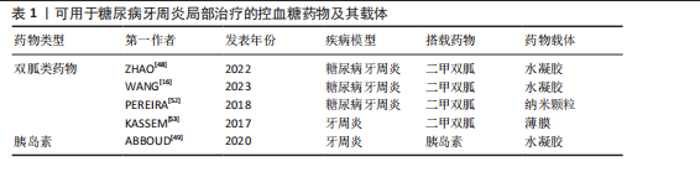

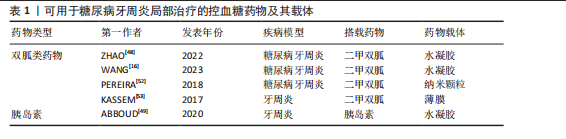

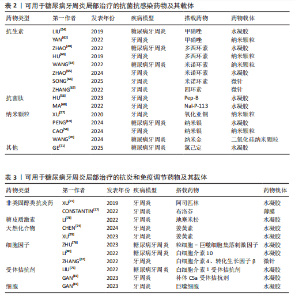

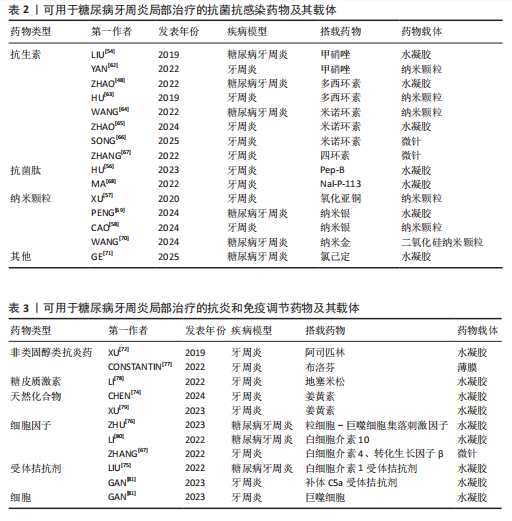

水平明显低于单纯牙周炎患者和牙周健康者,血清中核因子κB受体活化因子配体水平、血清核因子κB受体活化因子配体与骨保护素比值均显著高于单纯牙周炎患者和牙周健康者,提示糖尿病可导致成骨-破骨活动失衡、促破骨活动增强,并且这种对破骨活动的促进效应还与血糖控制水平有关[30]。糖尿病还会降低成骨细胞功能,导致成骨细胞中骨形成相关基因(如Runt相关转录因子2等)表达受损和细胞凋亡[31]。与糖尿病相关的白细胞介素17表达增强还可改变口腔微生物群,同时增加微生物群的致病性[32]。糖尿病也能通过激活晚期糖基化终末产物受体来加重牙周炎。高血糖会导致晚期糖基化终末产物积聚,晚期糖基化终末产物可直接发挥促炎/氧化作用或激活其受体信号,进而影响细胞功能、增强炎症反应和氧化应激,影响组织愈合[33]。 (2)牙周炎影响糖尿病控制:广泛的临床研究表明,牙周炎会影响糖尿病的发生、发展、预后。牙周炎可使高血糖风险增加33%,患2型糖尿病的风险增加1.24倍,同时还能够提高糖化血红蛋白水平[34-36]。同时,牙周炎还会影响糖尿病并发症的控制,如增加糖尿病肾病、糖尿病视网膜病变、糖尿病微血管病变风险[37-38]。 牙周炎中口腔局部微生物的失调、致病性增高,致病菌及其分泌的如脂多糖、二肽基肽酶、脯氨酰三肽基肽酶等毒力因子,可通过牙周袋破溃的袋内壁或通过消化道吸收进入血液循环,进入血液循环的细菌和毒力因子可促进全身炎症,加剧胰岛素抵抗,从而加重糖尿病[39]。牙周炎衍生毒力因子可以调节胰岛β细胞免疫炎症信号通路,使其先进入代偿状态,促进胰岛素分泌[40]。而后,在长期持续的毒力因子刺激下,胰岛β细胞进入失代偿状态:一方面,毒力因子可以选择性地定位于胰岛β细胞上,下调胰岛β细胞的特异性转录因子胰腺十二指肠同工酶1、NKX6.1转录因子的表达,诱导胰岛β细胞分化并丧失分泌胰岛素的能力[41-42];另一方面,牙周炎衍生的毒力因子可通过死亡受体通路和线粒体通路激活胰岛β细胞凋亡,如牙龈卟啉单胞菌直接刺激可以激活半胱天冬蛋白酶8、半胱天冬蛋白酶9、半胱天冬蛋白酶3导致胰岛β细胞凋亡[43]。除了通过胰岛β细胞损害胰岛素信号通路,牙周炎衍生的毒力因子还可通过肝细胞、脂肪细胞等糖尿病相关靶细胞损害胰岛素信号通路,影响糖尿病的发生、发展和预后。牙周炎衍生的毒力因子可通过干扰糖原合成酶激酶3、糖原合酶、糖原磷酸化酶、磷酸烯醇式丙酮酸碳羧化酶和葡萄糖6磷酸酶等酶的合成和表达,导致肝糖原分解增加、总肝糖原合成减少、糖异生增加,破坏肝细胞参与维持正常的血糖平衡;还可通过介导氧化应激、炎症反应和特定脂肪因子(如瘦素)的异常分泌,减少脂肪细胞对葡萄糖的摄取、脂肪分解增加,进而影响糖代谢[44-45]。 2.3 糖尿病牙周炎的局部给药治疗策略 糖尿病牙周炎涉及复杂的高血糖、细菌感染、炎症微环境、氧化应激、免疫失调、骨质流失等病理微环境,要求糖尿病牙周炎治疗用药应针对这些特点综合确定方案。目前临床对于糖尿病牙周炎的药物治疗,主要是机械清创术辅以局部或全身应用抗生素治疗。然而,全身给药存在药物不良反应大、牙周袋局部药物浓度低、需患者良好的依从性等局限,还可能导致口腔和肠道菌群失调。而局部给药可很好避免上述全身给药的问题,是糖尿病患者牙周炎给药方式的有利选择。 2.3.1 糖尿病牙周炎治疗药物的选择 控血糖药物:高血糖环境不利于糖尿病牙周炎的控制,血糖控制不佳还会影响患者的免疫功能,进而导致糖尿病牙周炎患者牙周组织局部病原体数量和致病性的增加[46]。高血糖还可通过多种途径导致氧化应激,如通过激活丝裂原活化蛋白激酶、核因子κB和嗜中性白细胞碱性磷酸酶3炎性小体刺激产生促炎细胞因子,加重牙周组织损伤[47]。因此,血糖控制对糖尿病牙周炎的治疗具有直接意义。目前,通过局部给药系统搭载治疗糖尿病牙周炎的控血糖药物多为双胍类药物和胰岛素[16,48-49],其他常用的控血糖药物如磺脲类药物和噻唑烷酮类药物,未来或也可被应用于局部给药治疗糖尿病牙周炎[50-51]。除以上几类药物外,尚未有其他控血糖药物(如胰高血糖素样肽1受体激动剂和α-葡萄糖苷酶抑制剂)用于糖尿病牙周炎治疗的报道,相信未来会出现更多极具潜力的牙周炎治疗药物。目前可用于糖尿病牙周炎局部治疗的控血糖药物及其载体,见表1。 抗菌抗感染药物:牙菌斑生物膜是牙周炎发病的始动因素,牙周炎与牙龈卟啉单胞菌、伴放线聚集杆菌、核梭杆菌等革兰阴性菌密切相关[19]。抗菌是牙周炎治疗的重要环节,主要通过机械清创治疗辅以抗菌剂实现。目前糖尿病牙周炎治疗最常用的是抗生素,如多西环素、甲硝唑、米诺环素等[48,54-55]。抗生素的抗菌机制可概括为干扰细菌蛋白质的合成、改变细菌细胞膜的通透性、影响细菌叶酸和核酸代谢、抑制细菌细胞壁合成。然而,应用抗生素会产生细菌耐药性,"

而作为免疫反应的早期成分之一的抗菌肽较抗生素更不易产生细菌耐药性。有研究发现一种内源性阳离子抗菌肽——抗菌肽Pep-B,是人β防御素1的功能性片段,可在发挥抗菌作用的同时促进牙周炎牙槽骨再生[56]。除了抗生素和抗菌肽,一些具有抗菌功能的纳米颗粒(如纳米银颗粒、氧化锌纳米颗粒、氧化亚铜纳米颗粒等)也被用作糖尿病牙周炎局部给药治疗系统中的抗菌成分[57-59]。其他如锌基沸石咪唑类金属有机框架材料、钛酸钡等具有抗菌功能的材料,也可作为抗菌成分参与糖尿病牙周炎的抗菌治疗[60-61]。可用于糖尿病牙周炎局部治疗的抗菌抗感染药物及其载体,见表2。 抗炎和免疫调节药物:糖尿病牙周炎患者的免疫失调不仅会导致牙周局部的炎症因子水平升高、影响抗菌效果,还会导致牙槽骨成骨-破骨活动失衡,加重牙槽骨流失和牙周组织破坏。多种抗炎药物如阿司匹林等非类固醇类抗炎药、姜黄素等天然化合物和多种生物制剂可用于牙周炎治疗,但除地塞米松外,鲜有其他糖皮质激素类药物在牙周炎治疗中的应用报道[72-74]。除直接使用抗炎药物外,还可通过使用细胞因子、受体拮抗剂、细胞疗法等途径调节患者体内免疫细胞的激活、趋化等免疫过程,实现对糖尿病牙周炎的治疗。例如,LIU等[75]将白细胞介素1的天然受体拮抗剂载入温敏性水凝胶中以治疗糖尿病牙周炎;ZHU等[76]利用粒细胞-巨噬细胞集落刺激因子增强调节性T细胞功能,增强糖尿病牙周炎治疗效果。可用于糖尿病牙周炎局部治疗的抗炎和免疫调节药物及其载体,见表3。 抗氧化应激药物:糖尿病和牙周炎均是氧化应激型炎症性疾病。在糖尿病牙周炎患者体内的多形核白细胞上,晚期糖基化终末产物其受体的相互作用会增强细胞氧化应激,破坏牙周组织[82]。一些抗氧化应激的药物可通过多种途径抑制氧化应激,抑制牙周组织的进一步破坏,从而为牙周组织的再生创造条件,如天然多酚类药物(如姜黄素等)能抑制核因子κB信号通路,白藜芦醇可激活核转录因子红系2相关因子2以减弱破骨细胞生成、调节细胞内活性氧、抑制牙周膜细胞凋亡[82-83]。可用于糖尿病牙周炎局部治疗的抗氧化应激药物及其载体,见表4。 促牙周组织再生药物:实现牙周组织再生是牙周炎治疗的终极目标。完全实现牙周组织再生目前仍是一个挑战,但已有很多研究证明了利用细胞、细胞因子等可促进牙周组织再生。FANG等[86]所开发的水凝胶便搭载了牛血清白蛋白纳米颗粒,以实现缓慢、持续释放硫化氢,募集间充质干细胞并促进血管生成和骨再生,促进糖尿病牙周骨的再生。另外,二甲双胍作为糖尿病的一线治疗药物,不仅能控制血糖,还具有促进成骨的功能,也有利于糖尿病牙周炎牙槽骨再生[16]。可用于糖尿病牙周炎局部治疗的促牙周组织再生药物及其载体,见表5。 其他治疗药物:作为一种抗高血脂症药物,他汀类药物可减少慢性牙周炎患者的牙齿脱落,抑制牙槽骨流失[92],还能发挥抗炎活性,抑制牙周胶原纤维退化,目前已被广泛研究用于牙周炎治疗[88]。牙周组织的血供丰富,诱导血管生成是实现牙周炎组织修复的必要条件。甲状腺素是人体内的重要激素之一,能通过多种机制诱导血管生成,已被证实可用于牙周炎治疗[93]。"

2.3.2 糖尿病牙周炎的局部给药途径 与全身给药相比,局部给药可避免全身给药产生的胃肠道不良反应、首过消除等问题,实现药物在牙周袋的控释,维持治疗药物的有效浓度。糖尿病牙周炎治疗的复杂性、牙周袋容量的有限性、口腔环境的复杂性,要求糖尿病牙周炎的局部给药治疗应尽可能精准控制药物剂量、贮存和释放。目前,已有很多药物递送系统用于糖尿病牙周炎的药物递送,如纳米颗粒、纤维、微粒、微针和水凝胶等。 纳米颗粒的应用范围广泛,可将药物封装在其内部或附着在其表面,将药物精准递送于牙周袋等区域,实现药物的控释和精确释放,但纳米粒的制备过程相对较为复杂且缺乏稳定性,在牙周袋内的保留时间相对较短[94]。纤维是沿牙周袋放置并用生物相容性黏合剂密封的线型药物输送系统,药物可填充在中空的纤维中或吸附在纤维上,从而实现药物的持续释放;纤维局部给药可用于一些给药相对困难的区域(如第二恒磨牙牙周袋的给药),减少给药不适,增加患者的依从性;但传统纤维通常不可降解,长期留存于口内会给患者带来不适,甚至可引起牙龈炎症,同时释药速度也相对较快,均在一定程度上限制了该材料的应用[95]。薄膜局部给药系统的优点在于它能够较好地与牙周袋的形状和大小相契合,直接插入牙周袋内治疗牙周炎。薄膜的厚度小于400 μm,能够很大程度上降低患者的不适感,有利于提高患者的依从性[96]。但是薄膜存在药物突释问题,也无法负载大剂量的药物,并且传统的薄膜材料(丙烯酸)不易降级吸收,容易留存在牙周袋内反而加重牙周炎症[96]。微粒是微米级的聚合物,包括微球、脂质体等,可在其内部封装药物,实现药物的控释。微球是指将药物溶解或分散在呈球状材料中,在牙周炎治疗中已广泛应用于四环素的递送[97]。脂质体是由胆固醇和天然无毒磷脂组成的球形人工囊泡,是一种优良的药物载体,兼具无毒、可降解、生物相容性优异等优点[98]。但不论是微球还是脂质体,均存在难以长期存留于牙周袋内的问题[96]。微针可穿透口腔黏膜或牙周组织实现无痛和快速给药,并且可实现药物控释[66]。但固体微针的药物递送设计复杂、空心微针易破损、涂层微针载药能力低,并且固体微针、空心微针、涂层微针使用后均会遗留在局部组织内,因此,结合了传统透皮给药系统和微针优点的溶解性微针愈来愈受关注[99]。水凝胶是一种广泛用于药物靶向递送的半固体系统,能较长时间地黏附在牙周袋内,并且载体材料种类很多,如聚乳酸-羟基乙酸共聚物、胶原蛋白、壳聚糖、聚丙烯酸等[100]。 2.4 用于糖尿病牙周炎局部给药治疗的水凝胶系统 2.4.1 水凝胶局部给药的特点 水凝胶是一种亲水性聚合物链交联的三维网络,结构类似天然细胞质基质,具有良好的生物相容性、高孔隙率、高含水量、可降解和自修复等优点,常装载各种小分子、药物、生长因子等功能性物质,广泛应用于生物工程领域[100]。 水凝胶具有高度可调节性,通过对其组分的化学修饰,可根据临床应用的实际需求调整水凝胶的特性,如刚度、溶胀率、生物降解性、黏弹性等。牙周袋的空间极为有限,这要求用于糖尿病牙周炎局部给药的水凝胶具有可注射性,能够进入并适应牙周袋的不规则形状,并能够搭载高浓度药物,保证局部药物浓度满足治疗需求[101]。口腔生理解剖特点、口腔功能运动、糖尿病牙周炎局部病理解剖特征等,要求用于糖尿病牙周炎治疗的水凝胶应具备适当的黏附性,使水凝胶载药系统能较长时间附着于牙周组织,提高药物的吸收和生物利用度。水凝胶的黏附性调节可利用具有生物黏合性的官能团(如邻苯二酚基团等)修饰水凝胶表面,也可利用氢键和分子间作用力等,实现水凝胶的自愈合[100,102-103]。根据糖尿病牙周炎治疗的多种需求联用用药时,可通过调节水凝胶的溶胀、生物降解或控制装载分子的释放时间实现药物控释和序贯给药[104]。 水凝胶功能设计具有多样性,可根据不同治疗需求调节水凝胶的特性,搭载不同的药物、材料,实现治疗剂的精确和持续输送。针对糖尿病牙周炎的病理环境,可赋予水凝胶抗菌、抗炎、抗氧化应激、免疫调节、促进牙周组织再生等多种功能,也可赋予水凝胶多种刺激响应性,协同控制糖尿病牙周炎的进展[71,85,105]。 2.4.2 糖尿病牙周炎的水凝胶给药治疗策略设计 (1)单一给药:水凝胶搭载药物的形式多样,可针对牙周炎治疗的某一特定需求搭载单一药物。例如,LIU等[54]设计了一种葡萄糖敏感的水凝胶控释给药系统,选择搭载甲硝唑这一牙周炎临床治疗常用的代表性抗生素,赋予水凝胶给药系统抗菌功能。搭载单一药物水凝胶的制备方法相对更为简单。除了针对糖尿病牙周炎病理微环境的某一方面负载相应药物,某些药物本身也具有多效性,不仅可从多方面满足糖尿病牙周炎的治疗需求,还可精简水凝胶的设计。例如,FENG等[85]在水凝胶中负载表没食子儿茶素没食子酸酯,一种药物便可实现抑制炎症细胞因子表达、抗氧化应激、抑制牙槽骨流失等多种作用。 (2)联合给药:鉴于抗菌、抗炎、抗氧化应激、免疫调节、促进牙周组织再生等多方面要求,应用多种药物协同治疗是糖尿病牙周炎治疗的趋势。多种药物不同的理化性质、药理作用、药物代谢动力学等特点为水凝胶给药系统的给药方案设计提出了新要求:水凝胶可以选择直接搭载药物,例如,ZHAO等[48]联合利用多西环素和二甲双胍作为供电子体,与苯硼酸官能化聚合物形成B-N配位键,将两种药物直接载入氧化葡聚糖和苯基硼酸改性聚乙烯亚胺水凝胶中协同治疗糖尿病牙周炎。除了直接搭载药物外,还可通过选择不同分子质量的药物、添加纳米颗粒或复合微球等方式实现药物的级联释放,这不仅适应了糖尿病牙周炎治疗的阶段性需求,还能避免药物突释情况,有利于延长局部药物的有效浓度及持续时间[69,71,106]。WANG等[16]将二甲双胍封装于介孔二氧化硅纳米颗粒中后与热敏性聚乳酸-聚乙二醇-聚乳酸嵌段共聚物组装,在早期快速释放水凝胶基质中装载的基质细胞衍生因子1,募集具有成骨潜力的间充质干细胞,而在后期则缓慢释放二甲双胍清除活性氧并促进成骨,通过实现对间充质干细胞的“募集-成骨”级联反应的精确操作促进了糖尿病牙周骨再生。 (3)智能给药:如前所述,糖尿病牙周炎的病理微环境十分复杂且并非一成不变,该病的复杂性、动态性加上口腔咀嚼运动、唾液分泌等局部解剖、功能特性,显著限制了传统水凝胶在糖尿病牙周炎治疗中的应用。针对糖尿病牙周炎微环境的变化及治疗需求,开发设计微环境响应型的智能水凝胶已成为糖尿病牙周炎的局部给药系统发展的趋势。 高血糖环境响应:葡萄糖响应性水凝胶能感知葡萄糖浓度水平的波动,由此激活并产生三维结构变化来控制药物释放的速率和剂量,即将高糖环境转化为控制水凝胶药物释放的反应因子。目前报道的葡萄糖响应性水凝胶主要包括3种类型:载葡萄糖氧化酶的水凝胶、含苯硼酸基团的水凝胶、载刀豆凝集素A的水凝胶等[107]。固定于pH值响应性水凝胶上的葡萄糖氧化酶可催化葡萄糖产生葡萄糖酸,使水凝胶基质发生收缩或膨胀,从而控制药物释放。载葡萄糖氧化酶水凝胶常用的化学交联剂具有细胞毒性,不过,目前已有多种方法可降低化学交联剂的细胞毒性,如选择低毒性天然交联剂、复合生物相容性材料、选用其他交联方法等[15,108]。XIAO等[15]通过复合环氧乙烷降低了壳聚糖水凝胶系统的细胞毒性并增强了其机械性能,制备葡萄糖响应性水凝胶可用于治疗糖尿病牙周炎。当葡萄糖浓度升高时,苯硼酸可与含顺式二醇基团的单糖结合形成稳定的葡萄糖-苯硼酸复合物,增加复合物的亲水性,导致药物递送载体的扩增或解体,随后触发药物释放以响应葡萄糖浓度水平的变化[109]。将苯硼酸可引入聚合物中可制备葡萄糖敏感型水凝胶,实现葡萄糖响应给药。FENG等[85]通过原位席夫碱反应将苯硼酸修饰的氧化海藻酸钠和羧甲基壳聚糖复合制成一种可注射水凝胶,以用于糖尿病牙周炎治疗。与同葡萄糖氧化酶类似,刀豆凝集素A也是一种天然来源蛋白质,具有出色的葡萄糖选择性[109]。刀豆凝集素A基治疗系统的设计原理主要基于多糖和刀豆凝集素A间的竞争性结合作用,如糖基化胰岛素-刀豆凝集素A合物会随着葡萄糖水平的升高而被破坏,致使胰岛素释放[110]。然而,刀豆凝集素A的不稳定性和细胞毒性在一定程度上限制了它的应用。 酸性环境响应:炎症和局部缺氧会导致糖尿病牙周炎患者的牙周组织中形成微酸性环境,因此,合理设计pH值响应性水凝胶可智能区分炎症和健康牙周组织,实现药物控释[111-112]。pH值敏感化学键的断裂和化学基团质子化是pH值响应性水凝胶的2种主要释药机制[112]:利用pH值敏感化学键将药物修饰到水凝胶上或通过酸性基团的去质子化,可引起水凝胶物理/化学性质(如溶解度、表面活性、疏水性等)或结构(如链构象、结构构型等)的改变,从而实现水凝胶对pH值变化响应释药。这类水凝胶中对pH值敏感的化学键包括酰胺键、酯键、腙键和亚胺键等[112]。目前鲜见pH值响应性水凝胶用于糖尿病牙周炎治疗的报道,但已被广泛用于牙周炎治疗领域,例如,CAI等[111]开发了一种自愈性羧甲基壳聚糖氧化葡聚糖水凝胶,能响应pH值变化释放药物促进牙周炎骨再生;YU等[113]制备了一种能在酸性环境(pH=5.4-6.6)中响应释放抗糖化剂N-苯基噻唑溴铵的壳聚糖基水凝胶;MOU等[114]制备了一种含米诺环素和氧化锌纳米颗粒的血清白蛋白微球,并将其引入pH值敏感性水凝胶中用于牙周炎治疗。 高活性氧环境响应:糖尿病牙周炎患者免疫反应的失衡可导致活性氧的过度产生和积聚,因此具有活性氧响应性水凝胶也是糖尿病牙周炎局部治疗的又一有力选择。当活性氧响应性水凝胶暴露于氧化应激环境中时,水凝胶骨架中的活性氧响应模块会被氧化破坏而使水凝胶网络的完整性受损,发生溶胀-收缩或凝胶-溶胶转变,从而实现对活性氧响应性药物释放[115]。常见的活性氧敏感性基团包括硫基、硒基、碲基、苯硼酸基等[115]。目前报道用于糖尿病牙周炎治疗的活性氧响应性水凝胶,它的响应功能多数是由苯硼酸基实现的。苯硼酸基的活性氧响应性源于硼酸基团和过氧键氧原子之间的重排,在生理条件下苯硼酸酯键可被氧化生成苯酚和硼酸[115]。据报道,苯硼酸基活性氧响应性水凝胶能有效响应局部高活性氧环境,进而释药治疗糖尿病牙周炎[48,85]。 苯硼酸基水凝胶也存在局限性,如它对葡萄糖的解离常数值通常在pH=9左右,远高于生理pH值,需降低解离常数以提高载体在生理条件下的葡萄糖敏感性,从而提高苯硼酸基水凝胶在糖尿病牙周炎治疗中的应用价值[116]。 除苯硼酸基外,由硫基、硒基等基团构成活性氧响应性模块水凝胶已被应用于糖尿病伤口治疗,有望在未来糖尿病牙周炎治疗中发挥用[117]。 其他响应类型:除了响应糖尿病牙周炎的病理微环境变化外,水凝胶还可响应某些物理因素实现智能控释给药。如温度响应性水凝胶、光响应性水凝胶、酶响应性水凝胶等以及多刺激共响应的水凝胶,均已被用于牙周炎治疗,这也为糖尿病牙周炎治疗的水凝胶载药系统设计提供思路[62,85,105,118-119]。"

| [1] MILANESI FC, GREGGIANIN BF, DOS SANTOS O, et al. Effect of periodontal treatment on glycated haemoglobin and metabolic syndrome parameters: A randomized clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol. 2023;50(1):11-21. [2] KWON T, LAMSTER IB, LEVIN L. Current Concepts in the Management of Periodontitis. Int Dent J. 2021;71(6):462-476. [3] TRINDADE D, CARVALHO R, MACHADO V, et al. Prevalence of periodontitis in dentate people between 2011 and 2020: A systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. J Clin Periodontol. 2023;50(5):604-626. [4] D’AIUTO F, GKRANIAS N, BHOWRUTH D, et al. Systemic effects of periodontitis treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes: a 12 month, single-centre, investigator-masked, randomised trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6(12):954-965. [5] CZESNIKIEWICZ-GUZIK M, OSMENDA G, SIEDLINSKI M, et al. Causal association between periodontitis and hypertension: evidence from Mendelian randomization and a randomized controlled trial of non-surgical periodontal therapy. Eur Heart J. 2019;40(42):3459-3470. [6] PIHLSTROM BL, MICHALOWICZ BS, JOHNSON NW. Periodontal diseases. Lancet. 2005;366(9499):1809-1820. [7] WU CZ, YUAN YH, LIU HH, et al. Epidemiologic relationship between periodontitis and type 2 diabetes mellitus. BMC Oral Health. 2020;20(1): 204. [8] NIBALI L, GKRANIAS N, MAINAS G, et al. Periodontitis and implant complications in diabetes. Periodontol 2000. 2022;90(1): 88-105. [9] GRAZIANI F, GENNAI S, SOLINI A, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiologic observational evidence on the effect of periodontitis on diabetes An update of the EFP-AAP review. J Clin Periodontol. 2018;45(2):167-187. [10] SIMPSON TC, CLARKSON JE, WORTHINGTON HV, et al. Treatment of periodontitis for glycaemic control in people with diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;4(4):Cd004714. [11] STAHL SS. Roentgenographic and bacteriologic aspects of periodontal changes in diabetics. J Periodontol (1930). 1948;19(4):130-132. [12] RYDOSZ J. Periodontal diseases treated with local applications of insulin in patients with diabetes. Czas Stomatol. 1967;20(10):1045-1054. [13] LÖE H. Periodontal disease: the sixth complication of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1993;16(1):329-334. [14] AIMETTI M, ROMANO F, TORTA I, et al. Debridement and local application of tetracycline-loaded fibres in the management of persistent periodontitis: results after 12 months. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31(3):166-172. [15] XIAO Y, GONG T, JIANG Y, et al. Fabrication and Characterization of a Glucose-sensitive Antibacterial Chitosan-Polyethylene Oxide Hydrogel. Polymer (Guildf). 2016;82:1-10. [16] WANG H, CHANG X, MA Q, et al. Bioinspired drug-delivery system emulating the natural bone healing cascade for diabetic periodontal bone regeneration. Bioact Mater. 2023;21:324-339. [17] WADE WG. The oral microbiome in health and disease. Pharmacol Res. 2013; 69(1):137-143. [18] HAN N, LIU Y, DU J, et al. Regulation of the Host Immune Microenvironment in Periodontitis and Periodontal Bone Remodeling. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(4): 3158. [19] SOCRANSKY SS, HAFFAJEE AD, CUGINI MA, et al. Microbial complexes in subgingival plaque. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25(2):134-144. [20] HAJISHENGALLIS G. New developments in neutrophil biology and periodontitis. Periodontol 2000. 2020;82(1):78-92. [21] WILLIAMS DW, GREENWELL-WILD T, BRENCHLEY L, et al. Human oral mucosa cell atlas reveals a stromal-neutrophil axis regulating tissue immunity. Cell. 2021; 184(15):4090-4104.e15. [22] CARNEIRO VM, BEZERRA AC, GUIMARãES MDO C, et al. Decreased phagocytic function in neutrophils and monocytes from peripheral blood in periodontal disease. J Appl Oral Sci. 2012;20(5):503-509. [23] YANG B, PANG X, LI Z, et al. Immunomodulation in the Treatment of Periodontitis: Progress and Perspectives. Front Immunol. 2021;12:781378. [24] MO K, WANG Y, LU C, et al. Insight into the role of macrophages in periodontitis restoration and development. Virulence. 2024;15(1):2427234. [25] GEMMELL E, SEYMOUR GJ. Immunoregulatory control of Th1/Th2 cytokine profiles in periodontal disease. Periodontol 2000. 2004;35:21-41. [26] GENCO R , BORGNAKKE WS. Risk factors for periodontal disease. Periodontol 2000. 2013;62(1):59-94. [27] WANG Z, LI S, TAN D, et al. Association between inflammatory bowel disease and periodontitis: A bidirectional two-sample Mendelian randomization study. J Clin Periodontol. 2023;50(6):736-743. [28] MANOUCHEHR-POUR M, SPAGNUOLO P, RODMAN H, et al. Comparison of neutrophil chemotactic response in diabetic patients with mild and severe periodontal disease.J Periodontol. 1981;52(8):410-415. [29] SALVI GE, COLLINS JG, YALDA B, et al. Monocytic TNF alpha secretion patterns in IDDM patients with periodontal diseases. J Clin Periodontol. 1997;24(1):8-16. [30] RIBEIRO FV, DE MENDONÇA AC, SANTOS VR, et al. Cytokines and bone-related factors in systemically healthy patients with chronic periodontitis and patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2011;82(8):1187-1196. [31] LU H, KRAUT D, GERSTENFELD LC, et al. Diabetes interferes with the bone formation by affecting the expression of transcription factors that regulate osteoblast differentiation. Endocrinology. 2003;144(1):346-352. [32] XIAO E, MATTOS M, VIEIRA GHA, et al. Diabetes enhances IL-17 expression and alters the oral microbiome to increase its pathogenicity. Cell Host Microbe. 2017; 22(1):120-128. e4. [33] TAYLOR JJ, PRESHAW PM, LALLA E. A review of the evidence for pathogenic mechanisms that may link periodontitis and diabetes. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40 Suppl 14:S113-134. [34] CHIU SY, LAI H, YEN AM, et al. Temporal sequence of the bidirectional relationship between hyperglycemia and periodontal disease: a community-based study of 5,885 Taiwanese aged 35-44 years (KCIS No. 32). Acta Diabetol. 2015;52(1):123-131. [35] LIN SY, LIN CL, LIU JH, et al. Association between periodontitis needing surgical treatment and subsequent diabetes risk: a population-based cohort study. J Periodontol. 2014;85(6):779786. [36] VADAKKEKUTTICAL RJ, KAUSHIK PC, MAMMEN J, et al. Does periodontal inflammation affect glycosylated haemoglobin level in otherwise systemically healthy individuals? - A hospital based study. Singapore Dent J. 2017;38:55-61. [37] WU HQ, WEI X, YAO JY, et al. Association between retinopathy, nephropathy, and periodontitis in type 2 diabetic patients: a Meta-analysis. Int J Ophthalmol. 2021; 14(1):141-147. [38] ZHANG X, WANG M, WANG X, et al. Relationship between periodontitis and microangiopathy in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. J Periodontal Res. 2021;56(6):1019-1027. [39] MIRNIC J, DJURIC M, BRKIC S, et al. Pathogenic mechanisms that may link periodontal disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus—the role of oxidative stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(18):9806. [40] BHAT UG, ILIEVSKI V, UNTERMAN TG, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide upregulates insulin secretion from pancreatic β cell line MIN6. J Periodontol. 2014;85(11): 1629-1636. [41] ILIEVSKI V, TOTH PT, VALYI-NAGY K, et al. Identification of a periodontal pathogen and bihormonal cells in pancreatic islets of humans and a mouse model of periodontitis. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):9976. [42] HUANG Y, XU Y, LU Y, et al. lncRNA Gm10451 regulates PTIP to facilitate iPSCs-derived β-like cell differentiation by targeting miR-338-3p as a ceRNA. Biomaterials. 2019; 216:119266. [43] ILIEVSKI V, BHAT UG, SULEIMAN-ATA S, et al. Oral application of a periodontal pathogen impacts SerpinE1 expression and pancreatic islet architecture in prediabetes. J Periodontal Res. 2017;52(6):1032-1041. [44] 晏彩霞,李燕.二型糖尿病与牙周炎微生物组的双向促进因素[J].中华老年口腔医学杂志,2021,19(4):241-246. [45] SU Y, YE L, HU C, et al. Periodontitis as a promoting factor of T2D: current evidence and mechanisms. Int J Oral Sci. 2023;15(1):25. [46] MIRANDA TS, FERES M, RETAMAL-VALDÉS B, et al. Influence of glycemic control on the levels of subgingival periodontal pathogens in patients with generalized chronic periodontitis and type 2 diabetes. J Appl Oral Sci. 2017;25(1):82-89. [47] MIRNIC J, DJURIC M, BRKIC S, et al. Pathogenic Mechanisms That May Link Periodontal Disease and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus-The Role of Oxidative Stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(18):9806. [48] ZHAO X, YANG Y, YU J, et al. Injectable hydrogels with high drug loading through B-N coordination and ROS-triggered drug release for efficient treatment of chronic periodontitis in diabetic rats. Biomaterials. 2022;282:121387. [49] ABBOUD AR, ALI AM, YOUSSEF T. Preparation and characterization of insulin-loaded injectable hydrogels as potential adjunctive periodontal treatment. Dent Med Probl. 2020;57(4):377-384. [50] YANG L, GE Q, YE Z, et al. Sulfonylureas for Treatment of Periodontitis-Diabetes Comorbidity-Related Complications: Killing Two Birds With One Stone. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:728458. [51] DI PAOLA R, MAZZON E, MAIERE D, et al. Rosiglitazone reduces the evolution of experimental periodontitis in the rat. J Dent Res. 2006;85(2):156-161. [52] PEREIRA ASBF, BRITO GAC, LIMA MLS, et al. Metformin hydrochloride-loaded PLGA nanoparticle in periodontal disease experimental model using diabetic rats. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(11):3488. [53] KASSEM AA, ISSA DA, KOTRY GS, et al. Thiolated alginate-based multiple layer mucoadhesive films of metformin forintra-pocket local delivery: in vitro characterization and clinical assessment. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2017;43(1):120-131. [54] LIU J, XIAO Y, WANG X, et al. Glucose-sensitive delivery of metronidazole by using a photo-crosslinked chitosan hydrogel film to inhibit Porphyromonas gingivalis proliferation. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;122:19-28. [55] LIN J, HE Z, LIU F, et al. Hybrid Hydrogels for Synergistic Periodontal Antibacterial Treatment with Sustained Drug Release and NIR-Responsive Photothermal Effect. Int J Nanomedicine. 2020;15:5377-5387. [56] HU Z, ZHOU Y, WU H, et al. An injectable photopolymerizable chitosan hydrogel doped anti-inflammatory peptide for long-lasting periodontal pocket delivery and periodontitis therapy. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;252:126060. [57] XU Y, ZHAO S, WENG Z, et al. Jelly-Inspired Injectable Guided Tissue Regeneration Strategy with Shape Auto-Matched and Dual-Light-Defined Antibacterial/Osteogenic Pattern Switch Properties. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2020;12(49):54497-54506. [58] CAO B, ZHANG J, MA Y, et al. Dual-Polymer Functionalized Melanin-AgNPs Nanocomposite with Hydroxyapatite Binding Ability to Penetrate and Retain in Biofilm Sequentially Treating Periodontitis. Small. 2024;20(37):e2400771. [59] KIARASHI M, MAHAMED P, GHOTBI N, et al. Spotlight on therapeutic efficiency of green synthesis metals and their oxide nanoparticles in periodontitis. J Nanobiotechnology. 2024;22(1):21. [60] ROLDAN L, MONTOYA C, SOLANKI V, et al. A Novel Injectable Piezoelectric Hydrogel for Periodontal Disease Treatment. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2023;15(37):43441-43454. [61] LIU Y, LI T, SUN M, et al. ZIF-8 modified multifunctional injectable photopolymerizable GelMA hydrogel for the treatment of periodontitis. Acta Biomater. 2022;146:37-48. [62] YAN N, XU J, LIU G, et al. Penetrating Macrophage-Based Nanoformulation for Periodontitis Treatment. ACS Nano. 2022; 16(11):18253-18265. [63] HU F, ZHOU Z, XU Q, et al. A novel pH-responsive quaternary ammonium chitosan-liposome nanoparticles for periodontal treatment. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;129:1113-1119. [64] WANG L, LI Y, REN M, et al. pH and lipase-responsive nanocarrier-mediated dual drug delivery system to treat periodontitis in diabetic rats. Bioact Mater. 2022;18:254-266. [65] ZHAO Z, WU C, HUANGFU Y, et al. Bioinspired Glycopeptide Hydrogel Reestablishing Bone Homeostasis through Mediating Osteoclasts and Osteogenesis in Periodontitis Treatment. ACS Nano. 2024; 18(43):29507-29521. [66] SONG YW, NAM J, KIM J, et al. Hyaluronic acid-based minocycline-loaded dissolving microneedle: Innovation in local minocycline delivery for periodontitis. Carbohydr Polym. 2025;349(Pt B):122976. [67] ZHANG X, HASANI-SADRABADI MM, ZARUBOVA J, et al. Immunomodulatory Microneedle Patch for Periodontal Tissue Regeneration[. Matter. 2022;5(2): 666-682. [68] MA S, LU X, YU X, et al. An injectable multifunctional thermo-sensitive chitosan-based hydrogel for periodontitis therapy. Biomater Adv. 2022;142:213158. [69] PENG G, LI W, PENG L, et al. Multifunctional DNA-Based Hydrogel Promotes Diabetic Alveolar Bone Defect Reconstruction. Small. 2024;20(10):e2305594. [70] WANG Y, CHU T, JIN T, et al. Cascade Reactions Catalyzed by Gold Hybrid Nanoparticles Generate CO Gas Against Periodontitis in Diabetes. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2024;11(24):e2308587. [71] GE X, HU J, QI X, et al. An Immunomodulatory Hydrogel Featuring Antibacterial and Reactive Oxygen Species Scavenging Properties for Treating Periodontitis in Diabetes. Adv Mater. 2024:e2412240. [72] XU X, GU Z, CHEN X, et al. An injectable and thermosensitive hydrogel: Promoting periodontal regeneration by controlled-release of aspirin and erythropoietin. Acta Biomater. 2019;86:235-246. [73] LI Z, LI G, XU J, et al. Hydrogel Transformed from Nanoparticles for Prevention of Tissue Injury and Treatment of Inflammatory Diseases. Adv Mater. 2022; 34(16):e2109178. [74] CHEN J, LUO A, XU M, et al. The application of phenylboronic acid pinacol ester functionalized ROS-responsive multifunctional nanoparticles in the treatment of Periodontitis. J Nanobiotechnology. 2024;22(1):181. [75] LIU Y, LIU C, WANG C, et al. Treatment of periodontal inflammation in diabetic rats with IL-1ra thermosensitive hydrogel. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(22):13939. [76] ZHU Y, WINER D, GOH C, et al. Injectable thermosensitive hydrogel to modulate tolerogenic dendritic cells under hyperglycemic condition. Biomater Sci. 2023;11(6):2091-2102. [77] CONSTANTIN M, LUPEI M, BUCATARIU SM, et al. PVA/chitosan thin films containing silver nanoparticles and Ibuprofen for the treatment of periodontal disease. Polymers. 2022;15(1):4. [78] LI N, XIE L, WU Y, et al. Dexamethasone-loaded zeolitic imidazolate frameworks nanocomposite hydrogel with antibacterial and anti-inflammatory effects for periodontitis treatment. Mater Today Bio. 2022;16:100360. [79] XU S, HU B, DONG T, et al. Alleviate Periodontitis and Its Comorbidity Hypertension using a Nanoparticle-Embedded Functional Hydrogel System. Adv Healthc Mater. 2023;12(20):e2203337. [80] LI W, WANG C, WANG Z, et al. Physically Cross-Linked DNA Hydrogel-Based Sustained Cytokine Delivery for In Situ Diabetic Alveolar Bone Rebuilding. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2022;14(22):25173-25182. [81] GAN Z, XIAO Z, ZHANG Z, et al. Stiffness-tuned and ROS-sensitive hydrogel incorporating complement C5a receptor antagonist modulates antibacterial activity of macrophages for periodontitis treatment. Bioact Mater. 2023;25:347-359. [82] SCZEPANIK FSC, GROSSI ML, CASATI M, et al. Periodontitis is an inflammatory disease of oxidative stress: We should treat it that way. Periodontol 2000. 2020; 84(1):45-68. [83] TAN W, LONG T, WAN Y, et al. Dual-drug loaded polysaccharide-based self-healing hydrogels with multifunctionality for promoting diabetic wound healing. Carbohydr Polym. 2023;312:120824. [84] TAN Y, FENG J, XIAO Y, et al. Grafting resveratrol onto mesoporous silica nanoparticles towards efficient sustainable immunoregulation and insulin resistance alleviation for diabetic periodontitis therapy. J Mater Chem B. 2022;10(25):4840-4855. [85] FENG Q, ZHANG M, ZHANG G, et al. A whole-course-repair system based on ROS/glucose stimuli-responsive EGCG release and tunable mechanical property for efficient treatment of chronic periodontitis in diabetic rats. J Mater Chem B. 2024;12(15):3719-3740. [86] FANG X, WANG J, YE C, et al. Polyphenol-mediated redox-active hydrogel with H(2)S gaseous-bioelectric coupling for periodontal bone healing in diabetes. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):9071. [87] ZHOU J, LI H, LI S, et al. Convertible Hydrogel Injection Sequentially Regulates Diabetic Periodontitis. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2025;11(2):916-929. [88] CHANG PC, DOVBAN AS, LIM LP, et al. Dual delivery of PDGF and simvastatin to accelerate periodontal regeneration in vivo. Biomaterials. 2013;34(38):9990-9997. [89] ISAAC A, JIVAN F, XIN S, et al. Microporous Bio-orthogonally Annealed Particle Hydrogels for Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2019; 5(12):6395-6404. [90] MA Y, JI Y, ZHONG T, et al. Bioprinting-Based PDLSC-ECM Screening for in Vivo Repair of Alveolar Bone Defect Using Cell-Laden, Injectable and Photocrosslinkable Hydrogels. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2017; 3(12):3534-3545. [91] LI H, WANG Q, XIAO Y, et al. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D(3)-loaded PLA microspheres: in vitro characterization and application in diabetic periodontitis models. AAPS Pharm SciTech. 2013;14(2): 880-889. [92] CUNHA-CRUZ J, SAVER B, MAUPOME G, et al. Statin use and tooth loss in chronic periodontitis patients. J Periodontol. 2006; 77(6):1061-1066. [93] MALIK MH, SHAHZADI L, BATOOL R, et al. Thyroxine-loaded chitosan/carboxymethyl cellulose/hydroxyapatite hydrogels enhance angiogenesis in in-ovo experiments. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;145:1162-1170. [94] KONG LX, PENG Z, LI SD, et al. Nanotechnology and its role in the management of periodontal diseases. Periodontology 2000. 2006;40(1):184. [95] CHOU SF, CARSON D, WOODROW KA. Current strategies for sustaining drug release from electrospun nanofibers. J Control Release. 2015;220:584-591. [96] WEI Y, DENG Y, MA S, et al. Local drug delivery systems as therapeutic strategies against periodontitis: A systematic review. J Control Release. 2021;333:269-282. [97] 刘迪,杨丕山,胡德渝,等.盐酸米诺环素脂质体控释凝胶改善大鼠实验性牙周炎的作用评价[J].华西口腔医学杂志, 2013,31(6):592-596. [98] 陆新月,吕慧侠.微球给药系统载体材料的研究进展[J].中国药科大学学报, 2018,49(5):528-536. [99] ZHUO Y, WANG F, LV Q, et al. Dissolving microneedles: Drug delivery and disease treatment. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2025;250:114571. [100] LI Q, WANG D, XIAO C, et al. Advances in Hydrogels for Periodontitis Treatment. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2024;10(5):2742-2761. [101] BOȘCA AB, DINTE E, MIHU CM, et al. Local Drug Delivery Systems as Novel Approach for Controlling NETosis in Periodontitis. Pharmaceutics. 2024;16(9):1175. [102] CHEN T, CHEN Y, REHMAN HU, et al. Ultratough, Self-Healing, and Tissue-Adhesive Hydrogel for Wound Dressing. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2018;10(39):33523-33531. [103] TALEBIAN S, MEHRALI M, TAEBNIA N, et al. Self-Healing Hydrogels: The Next Paradigm Shift in Tissue Engineering? Adv Sci (Weinh). 2019;6(16):1801664. [104] SPILLER KL, NASSIRI S, WITHEREL CE, et al. Sequential delivery of immunomodulatory cytokines to facilitate the M1-to-M2 transition of macrophages and enhance vascularization of bone scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2015;37:194-207. [105] LIU Y, LIU C, WANG C, et al. Treatment of Periodontal Inflammation in Diabetic Rats with IL-1ra Thermosensitive Hydrogel. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(22):13939. [106] WANG L, YANG H, ZHANG C, et al. A blood glucose fluctuation-responsive delivery system promotes bone regeneration and the repair function of Smpd3-reprogrammed BMSC-derived exosomes. Int J Oral Sci. 2024;16(1):65. [107] YANG J, CAO Z. Glucose-responsive insulin release: Analysis of mechanisms, formulations, and evaluation criteria. J Control Release. 2017;263:231-239. [108] ORYAN A, KAMALI A, MOSHIRI A, et al. Chemical crosslinking of biopolymeric scaffolds: Current knowledge and future directions of crosslinked engineered bone scaffolds. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018; 107:678-688. [109] CHEN Y, WANG X, TAO S, et al. Research advances in smart responsive-hydrogel dressings with potential clinical diabetic wound healing properties. Mil Med Res. 2023;10(1):37. [110] ZHANG R, TANG M, BOWYER A, et al. Synthesis and characterization of a D-glucose sensitive hydrogel based on CM-dextran and concanavalin A. React Funct Polym. 2006;66(7):757-767. [111] CAI G, REN L, YU J, et al. A Microenvironment-Responsive, Controlled Release Hydrogel Delivering Embelin to Promote Bone Repair of Periodontitis via Anti-Infection and Osteo-Immune Modulation. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2024;11(34):e2403786. [112] DING H, TAN P, FU S, et al. Preparation and application of pH-responsive drug delivery systems. J Control Release. 2022;348:206-238. [113] YU MC, CHANG CY, CHAO YC, et al. pH-Responsive Hydrogel With an Anti-Glycation Agent for Modulating Experimental Periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2016;87(6):742-748. [114] MOU J, LIU Z, LIU J, et al. Hydrogel containing minocycline and zinc oxide-loaded serum albumin nanopartical for periodontitis application: preparation, characterization and evaluation. Drug Deliv. 2019;26(1):179-187. [115] PU M, CAO H, ZHANG H, et al. ROS-responsive hydrogels: from design and additive manufacturing to biomedical applications. Mater Horiz. 2024;11(16): 3721-3746. [116] BROOKS WL, SUMERLIN BS. Synthesis and applications of boronic acid-containing polymers: from materials to medicine. Chem Rev. 2016;116(3):1375-1397. [117] LIU S, ZHANG Q, YU J, et al. Absorbable Thioether Grafted Hyaluronic Acid Nanofibrous Hydrogel for Synergistic Modulation of Inflammation Microenvironment to Accelerate Chronic Diabetic Wound Healing. Adv Healthc Mater. 2020;9(11):e2000198. [118] ZHANG L, WANG Y, WANG C, et al. Light-Activable On-Demand Release of Nano-Antibiotic Platforms for Precise Synergy of Thermochemotherapy on Periodontitis. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2020;12(3):3354-3362. [119] XU Y, LUO Y, WENG Z, et al. Microenvironment-Responsive Metal-Phenolic Nanozyme Release Platform with Antibacterial, ROS Scavenging, and Osteogenesis for Periodontitis. ACS Nano. 2023;17(19):18732-18746. |

| [1] | Liu Yang, Liu Donghui , Xu Lei, Zhan Xu, Sun Haobo, Kang Kai. Role and trend of stimuli-responsive injectable hydrogels in precise myocardial infarction therapy [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(8): 2072-2080. |

| [2] | Wang Zheng, Cheng Ji, Yu Jinlong, Liu Wenhong, Wang Zhaohong, Zhou Luxing. Progress and future perspectives on the application of hydrogel materials in stroke therapy [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(8): 2081-2090. |

| [3] | Guo Yuchao, Ni Qianwei, Yin Chen, Jigeer·Saiyilihan, Gao Zhan . Quaternized chitosan hemostatic materials: synthesis, mechanism, and application [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(8): 2091-2100. |

| [4] | Liu Hongjie, Mu Qiuju, Shen Yuxue, Liang Fei, Zhu Lili. Metal organic framework/carboxymethyl chitosan-oxidized sodium alginate/platelet-rich plasma hydrogel promotes healing of diabetic infected wounds [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(8): 1929-1939. |

| [5] | Bu Yangyang, Ning Xinli, Zhao Chen. Intra-articular injections for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the temporomandibular joint: different drugs with multiple combined treatment options [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(5): 1215-1224. |

| [6] | Liu Xinyue, Li Chunnian, Li Yizhuo, Xu Shifang. Regeneration and repair of oral alveolar bone defects [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(5): 1247-1259. |

| [7] | Wang Yu, Fan Minjie, Zheng Pengfei. Application of multistimuli-responsive hydrogels in bone damage repair: special responsiveness and diverse functions [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(2): 469-479. |

| [8] | Liu Xiaohong, Zhao Tian, Mu Yunping, Feng Wenjin, Lyu Cunsheng, Zhang Zhiyong, Zhao Zijian, Li Fanghong. Acellular dermal matrix hydrogel promotes skin wound healing in rats [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(2): 395-403. |

| [9] | Huang Xinxu, Zhang Xin, Wang Jian. Living microecological hydrogels promote skin wound healing [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(2): 489-498. |

| [10] | Li Qingshan, Li Runmeng, Gao Yuyang, Han Gang, Chen Jiying, Guo Quanyi. Magnetocaloric antitumor and osteogenic properties of magnetic bioactive glass scaffolds [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(14): 3494-3503. |

| [11] | Zhao Yingxin, Lang Tong, Meng Lingbing, Gao Yuxia. Causal relationship between diabetes mellitus and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: information analysis based on the GWAS database [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2026, 30(11): 2933-2948. |

| [12] | Lai Pengyu, Liang Ran, Shen Shan. Tissue engineering technology for repairing temporomandibular joint: problems and challenges [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2025, 29(在线): 1-9. |

| [13] | Wang Zheng, Cheng Ji, Yu Jinlong, Liu Wenhong, Wang Zhaohong, Zhou Luxing. Progress and future perspectives on the application of hydrogel materials in stroke therapy [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2025, 29(在线): 1-10. |

| [14] | Bai Jing, Zhang Xue, Ren Yan, Li Yuehui, Tian Xiaoyu. Effect of lncRNA-TNFRSF13C on hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha in periodontal cells by modulation of #br# miR-1246 #br# [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2025, 29(5): 928-935. |

| [15] | Wang Zilin, Mu Qiuju, Liu Hongjie, Shen Yuxue, Zhu Lili. Protective effects of platelet-rich plasma hydrogel on oxidative damage in L929 cells [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2025, 29(4): 771-779. |

| Viewed | ||||||

|

Full text |

|

|||||

|

Abstract |

|

|||||