Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research ›› 2018, Vol. 22 ›› Issue (15): 2396-2406.doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-4344.0760

Previous Articles Next Articles

Femoral revision of the hip: reason, type and different techniques

Feng Shuo, Zha Guo-chun, Guo Kai-jin, Chen Xiang-yang

- Department of Orthopedics, Affiliated Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University, Xuzhou 221000, Jiangsu Province, China

-

Online:2018-05-28Published:2018-05-28 -

Contact:Chen Xiang-yang, M.D., Chief physician, Department of Orthopedics, Affiliated Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University, Xuzhou 221000, Jiangsu Province, China -

About author:Feng Shuo, Master candidate, Department of Orthopedics, Affiliated Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University, Xuzhou 221000, Jiangsu Province, China -

Supported by:the Youth Medical Talent Project of Jiangsu Province, No. QNRC2016800; the Science and Technology Project of Xuzhou City, No. KC16SL111; the General Program of Health Planning Commission of Jiangsu Province, No. H2017081; the Key Project for Social Development in Jiangsu Province, No. BE2015627

CLC Number:

Cite this article

Feng Shuo, Zha Guo-chun, Guo Kai-jin, Chen Xiang-yang . Femoral revision of the hip: reason, type and different techniques[J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2018, 22(15): 2396-2406.

share this article

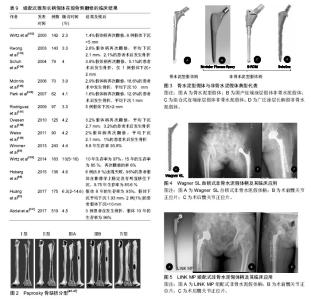

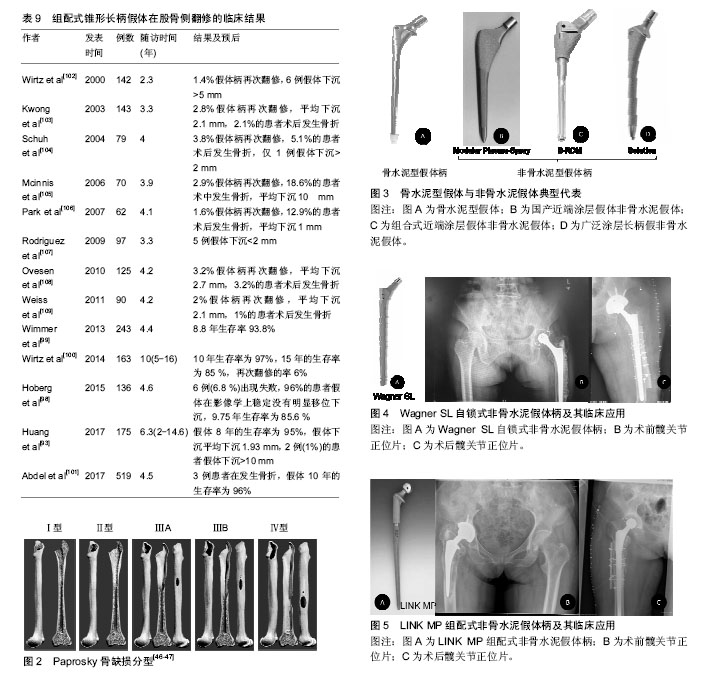

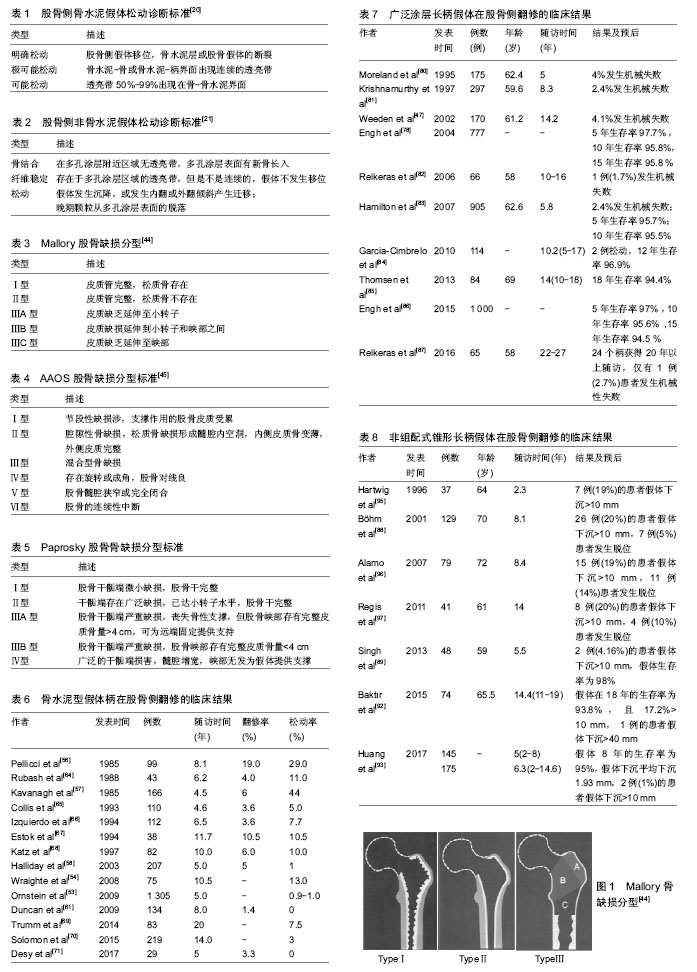

2.1 股骨侧翻修的发生率 Kurtz等[3-4]统计1990至2002年13年间美国进行的髋关节置换手术,共183 000例,其中约17.5%(31 000例)是翻修手术,且翻修的医疗费用占髋部保健支出的医疗总费用的19%,已经接近全膝关节置换翻修的2倍,预计到2030年,初次全髋关节置换的需求预计增长174%,翻修术到2026年增长137%。在英国,每年有66 000例髋关节置换手术,翻修患者数量超过10%,并预测英国到2030年翻修的患者将增加31%[5]。瑞典髋关节翻修手术也占到了髋部手术的 8% [6-7]。此外,股骨侧需要翻修的患者的所占比例较高,一项髋关节翻修多中心研究显示,在1 485例患者中有60%的患者需行股骨侧的翻修,单纯股骨翻修者占 23%,37%需行髋臼及股骨双侧翻修,而40%行仅髋臼侧翻修[8]。 2.2 股骨侧翻修的原因 2.2.1 无菌性松动 假体周围骨溶解引起假体无菌性松动被认为是晚期髋关节翻修的最常见原因,同时也是行髋关节翻修手术的主要指征之一[9-10]。引起假体松动的因素可以分为:机械性因素、生物学因素、患者的自身因素等:①机械性因素:主要是指假体—骨界面或骨水泥—骨组织界面力学上的失败。一方面是由于选择的假体与股骨不匹配或匹配不良,假体在假体-骨组织或骨水泥-骨组织界面固定不可靠,发生微动,影响生物型固定的假体与骨整合长入,或者影响水泥型假体的固定,导致假体松动。另一方面是应力遮挡,应力遮挡是指原本有骨单独所承担的负荷,由于置入假体后,负荷分担到假体和骨,原本的负荷现由两者共同承担,假体置入产生的负荷分担现象被称作应力遮挡。假体置入后股骨骨皮质承载一般较生理水平下降30%-60%,应力遮挡效应会使得假体周围骨代谢发生异常,诱发骨质疏松[11-12]。Gwam等[13]的研究显示,2009至2013年间美国258 461髋关节置翻修病例中,16.8%的患者因机械性因素而发生松动;②生物学因素:由假体关节面摩擦所产生的磨损颗粒激发巨噬细胞活动等引起的一系列反应致使发生骨溶解,又称“磨屑病”。其发生机制已经基本明确,由于人工髋关节在使用过程中关节面不断摩擦,产生磨损,积累的磨屑颗粒移位进入股骨侧,引发巨噬细胞、异物巨细胞将对其进行吞噬,从而激活巨噬细胞释放多种细胞因子,如肿瘤坏死因子α、白细胞介素1、白细胞介素6等,抑制成骨细胞的增殖,同时促进破骨细胞的增殖与成熟,大量破骨细胞的激活可造成假体周围局部骨溶解、吸收,久之骨量的大量丢失产生骨缺损,引起假体松动,磨损则会因假体的松动不稳定而加剧,故而磨损颗粒产生将进一步增加,逐渐形成“磨损-松动-磨损”恶性循环[14-16];③患者的自身因素:目前行髋关节置换的人群主要是老年患者,此类患者往往自身合并有糖尿病、肾病、骨质疏松等基础疾病,或者长期服用药物,骨质量不佳。然而,年轻患者其术后活动量较老年患者明显增多,使得关节磨损速度加快。Münger等[17]研究表明,当年龄每增加1岁,发现在假体置入后松动发生率下降了1.8%。目前肥胖的发病率急剧上升,有研究表明,体质量指数过高的患者术后由于负荷的增加,关节磨损速度也增快[18]。Godoysantos等[19]学者研究了基因多态性与假体早期置入松动失败之间的关系,纳入了58例患者,年龄均在50岁以上,进行早期假体置入松动失败中的MMP-1启动子多态性分析,结果显示,对照组2G等位基因频率为20.97%,基因型为1G/1G为67.74%,而试验组的2G等位基因频率为83.33%,2G/2G基因型为66.66%,表明MMP-1基因启动子的多态性可能是早期假体置入发生松动而失败的危险因素。 有学者列出了骨水泥型假体和非骨水泥型假体对于无菌性松动诊断的标准[20-21],见表1,2。通常在非骨水泥假体出现渐进性下沉,移位或出现透亮线认为假体存在不稳定,骨水泥假体在水泥骨界面处可见透过的连续的射线或者出现可透过非圆形射线表示可能的松动,目前已达成共识[21-22]。 2.2.2 感染 感染对于关节置换来说是一个灾难性的后果,也是翻修的重要原因。Bozic等[23]的研究显示,美国14.8%的患者因感染而导致髋关节置换手术失败。Havelin等[24]调查北欧3个国家,共280 201个髋关节置换病例中,其中感染的发生率15.8%(丹麦),15.0%(瑞典)和15.5%(挪威)。深层感染(subfascial extension of infection)是目前是翻修的第3个最常见的原因,其发生率在0.3%-2.2%,特别是假体周围感染对于关节科医生来说是一个非常严峻挑战[25-26]。细菌侵入髋关节后,移行至假体表面,黏附增殖形成一种膜,被称细菌生物被膜[27],细菌生物被膜的形成,机体的炎症细胞无法对其吞噬清除,躲藏在多糖基质内的细菌会释放各种炎性因子及酶类,造成局部的组织坏死和骨溶解,导致假体松动。不幸的是生物被膜内的细菌会产生耐药,且耐药机制尚不清楚,如何有效治疗仍是一大难点。目前,除了使用抗生素以外,有学者也将目光转到改进制造假体的材料上,Tokarski等[28]研究2000年至2013年间966例髋关节翻修的患者,其中536髋使用钛(Ti)髋臼组件,454髋使用钽(Ta)髋臼组件,经平均40.2月随访,其中7.3%翻修失败,其中144例(64 Ta,80 Ti)因感染而进行翻修,Ta组失败率为3.1%,而Ti组17.5%。因此,作者认为钽部件用于假体周围关节感染的患者时,其失败发生率较低,且作者还认为钽部件成功的原因可能是钽金属与骨融合的能力较强,充分的骨长入可以使感染菌无法存活在假体表面,钽材质的表面复杂的三维结构可能使细菌侵入困难。故对于股骨侧因感染而翻修的患者,钽制假体柄有望应用临床,进一步降低因感染而进行翻修的失败率。此外,Pulido等[29]确定了手术时间为假体周围关节感染一个独立的危险因素,同时这种现象在膝关节置换中也被发现,Namba等[30]报道,减少手术时间可以降低全膝关节置换术后感染的风险,且手术时间每增加 15 min,手术部位感染的风险增加9%[95%CI(4%- 13%)]。 2.2.3 假体脱位 据报道,初次髋关节置换术后假体脱位的发生率为0.5%-9.2%[31],在翻修患者中发病率更是高达28% [32-33]。一些研究认为术后90 d内,假体脱位是发生频率最高的并发症,是髋关节置换早期进行翻修手术的首要原因[32]。患者关节不稳定较高的脱位发生率一定程度是技术方面的原因,最近的研究报告发现采用后路或后外侧入路脱位发生率是前或前外侧的6倍[33],后路或后外侧入路术中进行细致软组织修复,其脱位的风险将会下降。假体的选择、安装位置与脱位发生的更为密切,股骨头尺寸的大小被认为是脱位发生的一个风险因素,尺寸为32 mm或更大的头部相比28 mm的脱位率将下降[34]。目前对于假体固定,髋臼侧不发生脱位的安全范围:髋臼外展(40±10)°,髋臼前倾(15±5)°,而在股骨侧,股骨假体柄需前倾(5±5)°,这是由于股骨的形态所造成[35]。Maruyama等[36]对成人尸体标本研究发现股骨向外侧弯曲是最常见的,占比为81%。约占16%股骨有一个双曲线即近端向外侧弯曲远端向内侧弯曲,仅在3%的股骨中发生向内侧弯曲,股骨前倾角平均为(9.8±8.5)°(-15°-34°),且男女无差别。需要的注意的是由于生物型股骨柄在髋关节置换中的广泛应用,其前倾范围为-17°-28°,较水泥柄为-30°-45°所提供前倾减少10°-20°,调整余地很小[37]。对于生物柄来说,术后不发生脱位,假体与股骨形态及多变的髓腔匹配程度亦是手术成功的关键。此外,良好的假体位置,不仅对恢复股骨正常的偏心距尤为重要,也是不发生脱位的重要因素。股骨的偏心距[38-39],是指股骨头到股骨干中心线的垂直距离,平均43 mm,范围27-57 mm。有研究显示,偏心距增加10 mm,外展肌力需求则降低10%[38]。偏心距增加,外展肌力臂增加,外展肌力需求减少,关节的应力减少,磨损降低,若股骨偏心距减小,股骨较骨盆距离小,使得髋关节外展肌等软组织松弛,髋关节的不稳定,易发生撞击、跛行、Trendelenburg步态,导致脱位风险增加。 2.2.4 假体周围骨折 髋关节周围假体骨折是关节置换术所面临的一个复杂的具有挑战性的问题,同时也是手术失败进行翻修又一因素。Abdel等[40]报道2014年澳大利亚假体周围骨折发生率占所有初次髋关节置换的10%。在假体周围骨折中,股骨侧假体周围发生骨折占主要部分[41]。假体周围骨折可发生在术中和术后,术中骨折主要发生在股骨柄假体置入股骨干侧时,其中骨质疏松症、类风湿关节炎、股骨干曾有手术史、假体柄选择不当、较差的手术的技术是术中发生股骨假体周围骨折的危险因素。术后假体周围骨折的诱发因素很多,如高龄、女性、创伤后骨关节炎、骨质疏松症和类风湿关节炎、股骨近端畸形、低能创伤、骨质溶解等。假体的类型也是一个非常重要的因素,早期有学者报道,骨水泥柄术中发生股骨侧骨折的发生率为0.1%-1%[41],Berry[42]报道美国梅奥医学中心中20 859例接受骨水泥柄置换的患者中术中骨折发生发生率0.3%,而在3 121接受非骨水泥柄发生率为5.4%。近期Sidler-Maier等[43]对报道术中股骨近端假体周围骨折总发生率范围为0.1%- 27.8%,其中非水泥柄固定柄的发生率较高文献报道为3%-18%,水泥柄的发生率仅0.3%-1%。面对如此高股骨近端假体周围骨折总发生率,临床上而对于患者的治疗,必须基于骨折类型、假体类型和患者自身情况进行,若患者股骨侧假体柄固定尚好可行切开复位内固定技术,而已经发生松动的柄需行翻修手术。 2.3 股骨侧翻修的术前规划 详尽的术前规划是股骨侧翻修至关重要的一步。术前对患者的平片分析评估必不可少,术前应拍摄骨盆正位片、髋关节正侧位片、蛙式位等,X射线片应具有良好的质量,以评估在骨水泥或骨假体界面的细微变化或指示感染的骨膜反应。髋关节正侧位片应具有足够的长度来评估固定假体的股骨峡部情况以及股骨干的完整性,必要时可拍摄患侧股骨正侧位或下肢全长正侧位片,以便评估患侧肢体的缩短及股骨前倾的情况。还应注意否存在股骨和髋臼骨质溶解、皮质缺损、骨质疏松、股骨畸形,以及骨水泥的剩余量和位置。同时利用模板术前与患者股骨X射线片进行比对,以便于初步确定选择翻修的假体的类型和大小。当然对于情况复杂的患者必要时也可行CT检查。此外,回顾患者的病史,初次置换的手术方法,置入假体的厂商、型号和尺寸等对于制定适当的手术计划也是至关重要。 假体周围缺损的评估:1988年Mallory分型被提 出[44],主要根据皮质骨和松质骨的骨缺损进行分型,虽然这种分类更简单和更有用,对于股骨重建方法有指导意义,但是它不能解决所有股骨骨缺损重建问题,应用范围有限,见表3及图1。 1993年D'Antonio等[45]报道了美国骨科医师学会(AAOS)分类系统(表4)。AAOS分类系统虽详细描述了股骨缺损等异常,但并没有为股骨的重建方法提供有效的选择的指导。 Weeden等[46-47]描述了一种基于的干骺端和股骨干的缺损状况进行分型的系统(表5)。与1993年D'Antonio等提出的AAOS分型相比,该种系统分析针对不同的分型提出了不同的手术治疗方法,明显有一定优势。因此被广泛的应用于临床。此外,Saleh等[48]也提供了一种股骨骨缺损的分型办法,但这种分型虽可靠有效,但较Paprosky分型在临床应用的不是很多(图2)。 2.4 植骨技术股骨侧骨缺损的应用 对于股骨侧骨缺损的处理,引入了髋臼侧处理的打压移植技术,并成功应用于股骨侧翻修手术。打压移植技术虽然在概念上比较简单,但在技术上要求苛刻,前提是已经缺损股骨髓腔可以接受松质骨同种异体移植,经过打压后形成一个新的髓腔。对于全层皮质缺损患者的处理又引入结构性植骨技术,一般采用金属网状物联合同种异体骨板或自体皮质骨在股骨外围进行环形加固,在股骨髓腔内进行打压细小的松质骨颗粒植骨,进行股骨形态再造,其早期可以取得良好的效果,但晚期有与宿主骨长入不良,甚至发生吸收塌陷的风险。早期一些学者对于打压植骨的临床结果表示担忧。Meding等[49]研究显示经过平均30个月的随访,在34例接受股骨打压植骨的患者中,38%患者发生假体下沉,且平均下沉10.1 mm,且12%的患者术中植骨时发生股骨骨折。Eldridge等[50]报道79例接受股骨打压植骨的患者在随访平均12.6个月后,有11%发生假体严重下沉(>10 mm)。Ornstein等[51]也报道108例接受股骨侧打压植骨的患者其中有39例在术后1年内发生股骨骨折。但近10年以来,由于对于植骨技术的认识加深,在操作上更加精细小心,很多股骨侧翻修患者采用打压植骨具有良好的结果。Sierra等[52]股骨侧翻修时打压植骨结合长度220 mm的股骨假体柄使用对42例患者进行评估,结果发现发生2例患者在术后股骨骨折,6例患者需要股骨再手术,假体10年的生存率为90%,长柄结合打压植骨的使用虽然并不能完全避免患者术中或术后骨折的问题,但发现长柄假体的使用患者术后股骨骨折发生率明显减少。Ornstein等[53]对于从1989到2002年瑞典1 305例接受股骨侧打压植骨翻修的患者进行5-18年长期的随访研究,在分析70例需再次接受翻修的患者的失败原因时发现,以无菌性松动为终点,假体15年的生存率为99.1%。Wraighte等[54]报道了75例股骨侧打压植骨翻修患者临床结果,平均随访为10.5年,其股骨侧假体生存率达到92%。 2.5 股骨侧假体的研究进展 2.5.1 骨水泥型假体 早期骨水泥型假体在股骨侧翻修使用比例较高,但从2010年以后在翻修中的比例有所下降。2012年英格兰、威尔士和北爱尔兰3个国家联合关节病例登记处中共有8 812例患者接受髋关节翻修手术,在股骨侧翻修的病例中,骨水泥型假体柄与非骨水泥型假体柄在病例中分别占28%和29% [55]。 早期骨水泥型假体应用于股骨侧翻修时,具有较高的失败率。Pellicci等[56]研究中发现使用骨水泥型假体进行髋关节置换翻修的99例患者,术后8.1年19%的患者需要再次行翻修手术,且股骨侧假体的松动率达到29%。Kavanagh等[57]研究中4.5年后约6%的患者需要再次翻修手术,但44%的患者在影像学上可看到股骨侧假体发生松动,鉴于早期骨水泥型假体应用令人沮丧的临床结果,学者们在不断探索改进,出现第3代骨水泥技术,即真空状态下进行骨水泥混合,减少气泡的产生,并利用加压灌注,增强了容积填充。加上髓腔灌洗,逆行水泥灌注等手段在翻修术上的出现使得骨水泥假体翻修成功率得到提高。Halliday等[58]应用第3代骨水泥技术行股骨柄翻,生存分析发现骨水泥假体10年生存率高达90.5%。Iorio等[59]报道非水泥型假体5年生存率为94%,骨水泥型假体达到92%。Weiss等[60]进行一项股骨侧翻修的患者大宗数据研究,纳入患者1 885例,其中812例使用非骨水泥假体柄,1 073例使用骨水泥型假体柄,结果显示骨水泥假体柄术后3年生存率要优于非骨水泥型,然而,在3年之后二者的生存曲线趋于融合。 Duncan[61]与Mounsey等[62]将骨水泥嵌套骨水泥技术(cement-in-cement technique)应用于股骨侧翻修的患者中,且取得了良好的疗效。2017年Cnudde等[63]对瑞典1 179例行骨水泥嵌套骨水泥技术进行研究,翻修术中使用Exeter和Lubinus两种骨水泥假体柄,结果显示,在第6年Exeter柄的生存率为91%,Lubinus柄为85%,骨水泥嵌套骨水泥技术中期随访效果满意。骨水泥嵌套骨水泥技术是仅仅将松动的假体取出后,在原有的骨水泥鞘床上重新进行灌注,结合尺寸上稍小的骨水泥柄重新进行固定。从股骨髓腔中去除原先固定好的骨水泥是不仅在技术上非常困难而且非常费时,水泥嵌套骨水泥技术较去除原有的水泥再次进行翻修方案相比,患者术中发生股骨骨折,股骨骨缺损量增多风险降低水泥嵌套骨水泥技术可为老年人的股骨侧翻修后假体柄的再次置入提供可靠的固定,可减少手术时间和并发症发生率,且目前随访来看其中期效果可观,但这种固定方式适用于假体柄与骨水泥界面之间发生松动,而骨水泥与股骨界面结合良好的病例。骨水泥型假体柄在股骨侧翻修的临床结果见表6。 2.5.2 非骨水泥型假体 鉴于早期骨水泥假体柄在髋关节翻修术临床结果不佳,骨水泥的固定效果遭到一些学者的质疑,于是非骨水泥固定应运而生(图3)。其中有两种的设计理念,一种设计早期通过假体柄和髓腔内的皮质的压配,产生摩擦而使假体稳定,晚期是由于假体表面带有一些特殊孔或颗粒涂层有骨长入,假体与宿主骨骨结合从而达到生物学固定。而另一种设计是不仅通过平滑假体柄和髓腔内的皮质的压配,而且假体设计成自锁式,通过的螺钉固定即刻就可获得远期稳定。 (1)近端涂层假体:近端涂层假体柄的特点是在假体的近端约1/3或1/2覆盖有微孔的涂层。然而,应用近端涂层假体进行股骨侧翻修时的临床结果较差,Berry等[72]回顾了一组375例使用近端涂层假体进行翻修患者资料,26%的患者术中发生股骨的近端发生骨折,以股骨无菌松动为终点假体8年生存率为20%,且发现术前的骨缺损程度与假体的存活率密切相关。Malkani等[73]报道股骨近端骨折术中发生率为45.9%,且发生骨折的患者,在术后4年患者的存活率仅为58%,显著高于未发生骨折的患者,且证实股骨近端缺损越大骨量丢失越多的患者越容易在术中发生骨折。此外,近端涂层假体柄在翻修时的骨折并发症发生率较高。 由于股骨侧在翻修时,干骺端存在不同的缺损,假体很难在初始阶段获得很好的稳定,无法在后期形成骨张入的生物学固定,因此无法获得稳定的股骨近端固定成为近端涂层假体柄翻修失败的首要原因,因此,鉴于近端涂层假体柄的设计特点,在应用时应当特别注意翻修病例选择,建议对于PaproskyⅠ型股骨骨缺损的患者且其近端骨缺损较少可在翻修时选用此假体。 (2)组合式近端涂层假体:组合式近端涂层假体柄的特点是采用头颈分离,颈柄分离,不同组件,采用双锥度连接。股骨头和股骨颈分离与普通假体一样,可调整头的大小来调整下肢的长度及髋关节的稳定性,不同的是对于股骨颈和股骨柄采用分离连接,一方面可以更方便的调整股骨的前倾角,另一方面对于根据股骨的形态选择合适的假体柄,针对股骨形态各异提供了更多的选择。股骨近端骨质丢失的是进行近端固定的难题,组合式近端涂层假体柄,在股骨柄的选择上留有更大的余地,有更多的型号可以选择,可在多变的股骨近端达到最佳的适配,一定程度上优于非组合式的假体柄,但其适用性仍受限,组合式近端涂层假体柄在Paprosky Ⅰ型和Ⅱ型患者的翻修术中效果良好[74],然而,对于股骨缺损较大的患者,结果很差。McCarthy等[75]在一项回顾性研究中,纳入对67例接受组合式近端涂层假体翻修患者,其中78%的患者股骨缺损类型是Paprosky Ⅲ型或Ⅳ型,术后进行平均14年的随访,结果显示假体14年的生存率为60%。 近端涂层的骨长入对于关节内的磨屑颗粒有一定程度上阻挡作用,避免迁移进入股骨远端而发生骨溶解,Bolognesi等[76]进行了一项随机前瞻性试验,比较了使用S-ROM假体中使用羟基磷灰石涂层袖套或多孔涂层袖套的不同,术后平均4年随访,发现对于Paprosky Ⅲ型骨缺损患者使用羟基磷灰石涂层袖套实更有利于骨生长,在3.9年时,假体的生存率为95%,此外Adolphson等[77]报道了22例使用组合式近端涂层假体进行翻修患者经过平均6年随访的临床结果,19例患者翻修后骨溶解显著减少,没有1例患者出现假体松动或沉降,但有4例患者出现轻度大腿不适或疼痛,影像学发现近端涂层的骨长入良好,同时也说明其对于关节内的磨屑颗粒有一定程度上阻挡作用,有效的降低骨溶解。 (3)广泛涂层长柄假:广泛涂层长柄假体的在翻修术中的设计理念是绕过股骨近端的缺损部位,假体在稍远端通过与股骨干髓腔皮质的压配,从而获得可靠的稳定性。比较经典的广泛涂层长柄假体如DePuy的Solution、Zimmer的Fullcoated、AML假体等,尽管广泛涂层长柄假体有近端应力遮挡的缺陷,这种假体在临床上收到很多医生的青睐,翻修过程相对容易,且成功率相对较高。Weeden等[46]研究了188例广泛涂层长柄假体翻修的患者,平均随访时间为14.2 年,发现患者Paprosky Ⅱ型或ⅢA型骨缺损的患者为失败率5%,而Paprosky ⅢB型骨缺损患者的失败率为21%,且机械性松动的发生率为4.1%。广泛涂层长柄假体的轴性和旋转稳定性依赖于其在股骨峡部的有效固定,而Paprosky ⅢB型骨缺损患者的失败率较高。Jr等[78]报道26髋,其股骨近端皮质缺乏平均大于10 cm延伸至小转子,平均随访13.3年,假体10年存活率为89%,15%患者出现机械松动。Jr等[78]也证实这一问题,是严重骨缺损导致力学不稳,假体与股骨干髓腔皮质的不能得到良好压配,失去可靠的稳定性从而降低了假体的存活率。Sporer等[79]调查了51例广泛涂层长柄假体翻修患者资料,其中Paprosky ⅢA型股骨缺损患者17例,ⅢB型26例,Ⅳ型8例,4.2年后26例Paprosky ⅢB型骨缺损患者中11发生失败,髓腔直径> 19 mm的患者中失效率为18%。此外,Moreland等[80-81]学者也发现假体骨长入与髓腔的压配填充程度有关,髓腔填充达在90%以上,术后假体下沉将小于2 mm,假体稳定尚好,髓腔填充达<75%的患者在术后假体下沉大于2 mm,大多假体失去稳定性。因此,全涂层单柄假体失败率髓腔直径相关,其稳定性依赖于其在股骨峡部的有效固固定,PaproskyⅡ型和ⅢA型股骨假体周围骨折尚获得较好的疗效,部分Paprosky ⅢB型骨缺损且髓腔直径<19 mm的患者也可获得较高的成功率,但缺损较大的患者如Paprosky ⅢB型或Ⅳ型骨缺损,其失败率很高,假体在股骨峡部无法获得有效固定。 广泛涂层长柄假体的长期临床结果也令人满意[80-87],见表7。Reikeras 等[82,87]对于1988到1993年间65例(66髋)接受广泛涂层长柄假体的患者进行研究,平均年龄为58岁,经历10-16年随访时,仅1例(1.7%)发生机械失败,经历22-27年随访时,21例患者死亡,其中24个柄获得20年以上随访,仅有1例股骨缺损分型是Paprosky Ⅳ型患者发生机械性失败,其余患者没有出现明显的大腿疼痛,影像学上发现患者没有松动迹象。Thomsen等[85]也发现广泛涂层长柄假体在翻修患者中18年生存率达到了94.4%,广泛涂层长柄假体远期仍可获得优良的临床结果。 (4)非组配式锥形长柄假体:全髋关节置换翻修术后如何避免股骨骨量丢失是非常具有挑战性,广泛涂层长柄假体,由于其在股骨近端有应力遮挡,增加术后患者股骨近端骨量的丢失,获且在Paprosky ⅢB和Ⅳ型股骨骨缺损患者中固定效果不佳。致使很多学者,在广泛涂层长柄假体的基础上进行改进,且鉴于近中段存在骨缺损,假体固定稳定性差,因此在设计上采用继续加长柄的长度的方法,使假体从近中段固定转向远端固定,这样可以跨过无支撑能力的近端的骨缺损区,柄在形态上也将圆柱形变成锥形。锥形柄插入到远端髓腔,随着负荷增大嵌插达到髓腔程度越深,从而获得很好的初始稳定性,并对于锥形柄的表面进行处理,使得其可以满足骨长入的需求,在远期形成生物固定。采用锥形设计的柄如Zweymuller系统中的SL-PLUS非骨水泥柄和Wagner Self-Locking (SL)自锁式非骨水泥假体柄。Wagner SL假体柄在临床应用广泛,其锥形柄由钛铝铌合金制成,并且在设计上很有特点,锥形柄的侧面增加了8条纵嵴,使假体的在髓腔中有着很好的旋转稳定性,同时表面为微孔喷砂涂层,可提供骨整合条件,确保继发稳定性(图4)。Wagner SL假体柄在翻修时早中期效果良好。Böhm等[88]报道了患者在接受Wagner SL柄翻修术后的髋关节在平均4.8年后,其疼痛、髋关节的功能和活动范围有的显著改善。Singh等[89]结果中显示使用Wagner SL假体翻修术后Harris髋关节评分也从术前为42分提高到86分。此外,Sandiford[90]与Bischel等[91]将报道中也证实了Wagner SL假体柄在翻修时早中期效果良好。关于Wagner SL假体柄在翻修的远期效果,Bakt?r等[92]对于74例患者进行长达14.4年的长期随访研究,生存分析发现假体18年的生存率为93.8%。Huang等[93]研究中发现假体8年的生存率为95%,假体下沉平均下沉1.93 mm,患者Harris髋关节评分也从术前为42分提高到86.1分,患者的满意度达92.3%,非组配式锥形长柄假体取得了良好的远期效果。此外,Kolb等[94]对采用Zweym Uller非骨水泥型置换假体的208髋(94例) 进行报道,平均随访20年,假体20年的存活率达到96%,假体长期结果令人满意。非组配式锥形长柄假体在股骨侧翻修的临床结果见表8。 (5)组配式锥形长柄假体:组配式锥形长柄假体在股骨侧翻修的临床结果见表9及图5。虽然非组配式锥形长柄假体的翻修效果比较好,但很多学者作者发现这种假体在置入后发生下沉的比例相对较高,且在复杂修复手术中,组配式锥形长柄假体所能提供的选择性较小,故而组配式锥形长柄假体得到了发展。组配式假体具有一定的弧度,在旧的骨床上获得远端即刻锚定,通过压配获得初始稳定性,且柄体远端创新扁锥设计减少假体对远端股骨的撞击,后期则是通过骨整合长入确保继发稳定性,8条纵行脊状突起可嵌入内侧皮质,提供良好旋转稳定性,锥形设计防止假体下沉。这种假体应用于临床失败率较低,Hoberg等[98]报道了136例行组配式锥形长柄假体患者,平均随访4.6年,仅6例(6.8%)出现失败。组配式锥形长柄假体柄体近端为可调节offset设计,更符合股骨解剖学特点,其对于肢体长度,股骨偏心距,前倾角和软组织张力的调节有更大可变性,其早中期的效果优良。Wimmer等[99]报道假体 8.8年生存率为93.8%。Wirtz等[100]报道假体10年生存率为97%,15年的生存率为85%,远期效果也十分可观。Abdel等[101]对519例行组配式锥形长柄假体患者进行平均随访4.5年的随访,发现Harris髋关节评分也从术前为51分提高到76分,应用组配式锥形长柄假体术后患者髋关节功能良好。翻修术中组配式锥形长柄假体能达到坚强固定,患者髋关节功能良好。 2.6 股骨侧翻修假体的选择 骨水泥在骨与假体之间既没有黏合作用也不发生化学反应,其固定作用仅靠面团期的塑形特点,将骨水泥压入骨与假体之间固化后镶嵌,骨水泥向骨小梁中渗透,松质骨得到加固后可以承受形变力量,所以其要求股骨近端有较好的松质骨。因此对于Mallory分型中Ⅰ型缺损,皮质管完整,松质骨存在的翻修病例可使用骨水泥假体固定,然而对于大多数翻修手术而言,由于松质骨几乎完全被破坏,骨面较硬且光滑,股骨存在严重的骨缺损和严重髓腔骨硬化,骨水泥与骨壁的锚固作用降低,难以达到较好的微内锁固定,同时股骨形态也变得很不规则,使得假体周围的骨水泥层厚度不均,容易产生应力集中;另一方面,骨水泥具有一定的毒性,对循环系统、呼吸系统以及凝血功能都有不良影响,术中可发生骨水泥置入综合征,骨水泥凝固时发生热容易造成翻修股骨侧骨组织损伤加大,因此,翻修手术目前一般不建议采用骨水泥固定。若采用骨水泥固定则需要进行相应的植骨,重建骨鞘,填充松质骨后,进行股骨形态再造,进行骨水泥充填固定,其早期可以取得良好的效果,但晚期有与宿主骨长入不良,甚至发生吸收塌陷的风险。 对于翻修患者骨水泥假体可适用以下人群:Mallory分型中Ⅰ型缺损股骨近端皮质管完整,松质骨存在的患者;年龄较大,预期寿命不长的患者伴有严重骨质疏松患者;无法行非骨水泥假体翻修的患者;因感染而进行翻修使用含抗生素骨水泥的患者。对于骨水泥单体过敏反应的患者应当慎用。 对于股骨侧翻修选择非骨水泥型假体固定而言,非骨水泥固定的假体柄种类较多,明确股骨侧的分型对于假体的选择至关重要,一般临床上更多应用Paprosky分型指导临床治疗。PaproskyⅠ型股骨骨缺损的患者其股骨干骺端微小缺损,股骨干完整在翻修时可选用近端涂层假体柄,针对的股骨近端多变的患者可选用组合式近端涂层假体柄,可达到最佳的适配。在一部分PaproskyⅡ患者中虽然干骺端存在广泛缺损,已达小粗隆水平,但股骨干完整,可以提供有效的骨性支撑,也可使用组合式近端涂层假体柄。而对于股骨近端的缺损部位较大的患者如Paprosky Ⅱ型或ⅢA型可选用广泛涂层长柄假体,绕过近端缺损在稍远端通过与股骨干髓腔皮质的压配进行固定。然而对于Paprosky ⅢB和Ⅳ型股骨骨缺损患者,其股骨骨量严重缺损以上的非骨水泥假体无法达到良好的固定效果,可选择远端固定假体如非组配式锥形长柄假体与组配式锥形长柄假体,组配式锥形长柄假体出现对于患者肢体长度、股骨偏心距、前倾角和软组织张力的调节有更大可变性,但术中容易发生骨折,且手术时间较长,操作复杂。对于非骨水泥假体翻修固定失败的患者再次选择时应当慎重。严重的股骨骨质疏松,无法提供翻修假体可靠的固定,股骨髓腔严重狭窄也是非骨水泥型假体应用的禁忌。 2.7 股骨侧翻修的并发症 术中出现股骨骨折是其常见且严重的并发症。这种现象多见于行非骨水泥长柄假体翻修的患者。对于翻修的患者而言,其假体松动后会产生应力侧股骨髓腔内侧皮质增厚,张力侧外侧皮质变薄的现象,使得髓腔的形态发生改变,在术中扩髓或置入假体时已发生骨折,此外,使用组配式假体由于手术操作复杂,术中安装假体及复位困难已发生术中骨折。对于术中的股骨骨折可以通过精细的手术操作如在在骨缺损区周围采用捆绑带或钢丝进行预捆绑、组配式假体置入时仔细耐心,避免暴力操作等方法可预防或避免术中骨折的发生。 翻修术组较初次置换手术组患者的平均年龄明显要高,术前合并症、手术时间、手术出血量及住院时间术后并发症均明显多于初次置换手术组,翻修手术的患者易出现感染、髋关节脱位、深静脉血栓等术后并发症。充分的术前准备、术前全面手术风险评估至关重要,此外,根据术式的不同摆放适宜的术后体位,如后入路应保持外展中立位;及时的了解切口情况,发现切口有渗血、渗液及时更换敷料,加强术后感染的预防和处理;合理规范的抗凝治疗联合鼓励患者床上活动或及早下床活预防深静脉血栓的形成也手术成功的关键,密切观察病情变化,预防并发症发生,一旦发生并发症,应做到早发现、早处理。 "

| [1] Callaghan JJ, Bracha P, Liu SS. Survivorship of a Charnley total hip arthroplasty. A concise follow-up, at a minimum of thirty-five years, of previous reports. J Bone Joint Surg Am.2009;91(11): 2617.[2] Parvizi J, Sullivan T, Duffy G, et al. Fifteen-year clinical survivorship of Harris-Galante total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19(6): 672-677.[3] Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Schmier J, et al. Future clinical and economic impact of revision total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am.2007;89(Suppl 3): 144-151.[4] Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, et al. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(7): 1487-1497.[5] Patel A, Pavlou G, Mújicamota RE, et al. The epidemiology of revision total knee and hip arthroplasty in England and Wales. Bone Joint J. 2015;97-B(8): 1076.[6] Sporer SM, Paprosky WG, O'Rourke MR. Managing bone loss in acetabular revision. J Bone Joint Surg Am.2005;55(7): 287-297.[7] Haddad FS, Rayan F. The role of impaction grafting: the when and how. Orthopedics. 2009;32(9). doi: 10.3928/01477447-20090728-19. [8] Bozic KJ, Durbhakula S, Berry DJ, et al. Differences in patient and procedure characteristics and hospital resource use in primary and revision total joint arthroplasty: a multicenter study. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20(7 Suppl 3): 17-25.[9] Prokopetz Julian JZ, Elena L, Bliss RL, et al. Risk factors for revision of primary total hip arthroplasty: a systematic review.BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13(1): 251.[10] Wright EA, Katz JN, Baron JA, et al. Risk factors for revision of primary total hip replacement: results from a national case-control study. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64(12):1879-1885.[11] 王强,杨民,徐祝军.全髋置换影响应力遮挡效应的相关因素[J].中国组织工程研究与临床康复,2009,13(4):739-742.[12] Piao C, Wu D, Luo M, et al. Stress shielding effects of two prosthetic groups after total hip joint simulation replacement. J Orthop Surg Res. 2014;9(1): 1-8.[13] Gwam CU, Mistry JB, Mohamed NS, et al. Current epidemiology of revision total hip arthroplasty in the United States: National Inpatient Sample 2009 to 2013. J Arthroplasty. 2017.[14] 郝云甲.人工髋关节翻修术中股骨侧骨缺损的处理及假体的选择[D].吉林大学, 2014.[15] 简小飞.远端生物固定翻修柄在非感染性高龄患者髋关节股骨侧翻修中的应用[J].武汉大学, 2015.[16] Boyce BF, Li P, Yao Z, et al. TNF-alpha and pathologic bone resorption. Keio J Med. 2005;54(3): 127.[17] Münger P, Röder C, Ackermann-Liebrich U, et al. Patient-related risk factors leading to aseptic stem loosening in total hip arthroplasty: A case-control study of 5,035 patients. Acta Orthop. 2006;77(4): 567.[18] Hanna SA, Mccalden RW, Somerville L, et al. Morbid obesity is a significant risk of failure following revision total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2017.[19] Godoysantos AL, D'Elia CO, Teixeira WJ, et al. Aseptic loosening of total hip arthroplasty: preliminary genetic investigation. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(2): 297.[20] Harris WH, Jr MCJ, O'Neill DA. Femoral component loosening using contemporary techniques of femoral cement fixation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64(7): 1063.[21] Engh CA, Bobyn JD, Glassman AH. Porous-coated hip replacement. The factors governing bone ingrowth, stress shielding, and clinical results. J Bone Joint Surg Bm.1987;69(1): 45.[22] Hartman CW, Garvin KL. Femoral fixation in revision total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(24): 2311-2322.[23] Bozic KJ, Kurtz SM, Lau E, et al. The epidemiology of revision total hip arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am.2009; 91(1): 128-133.[24] Havelin LI, Fenstad AM, Salomonsson R, et al. The Nordic Arthroplasty Register Association. Acta Orthop. 2009;80(4): 393-401.[25] Ong KL, Kurtz SM, Lau E, et al. Prosthetic joint infection risk after total hip arthroplasty in the Medicare population. J Arthroplasty.2009;24 (6 Suppl):105.[26] Lee KJ, Goodman SB. Identification of periprosthetic joint infection after total hip arthroplasty. J Orthop Trans. 2015;3(1): 21-25.[27] Singh PK, Parsek MR, Greenberg EP, et al. A component of innate immunity prevents bacterial biofilm development. Nature. 2002; 417(6888): 552-555.[28] Tokarski AT, Novack TA, Parvizi J. Is tantalum protective against infection in revision total hip arthroplasty? Bone Joint J. 2015;97-B(1):45.[29] Pulido L, Ghanem E, Joshi A, et al. Periprosthetic joint infection: the incidence, timing, and predisposing factors. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(7): 1710-1715.[30] Namba RS, Inacio MC, Paxton EW. Risk factors associated with deep surgical site infections after primary total knee arthroplasty: an analysis of 56,216 knees. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(9): 775.[31] Fernández-Fairen M, Hernández-Vaquero D, Murcia-Mazón A, et al. Inestabilidad de la artroplastia total de cadera. Una aproximación desde los criterios de la evidencia científica. Revista Espaola De Cirugía Ortopédica Y Traumatología. 2011;55(6): 460-475.[32] Capóngarcía D, Lópezpardo A, Alvespérez MT. Causes for revision surgery in total hip replacement. A retrospective epidemiological analysis. Revista Española De Cirugía Ortopédica Y Traumatología. 2016;60(3):160-166.[33] Sanzreig J, Lizaurutrilla A, Mirallesmuñoz F. Risk factors for total hip arthroplasty dislocation and its functional outcomes. Revista Española De Cirugía Ortopédica Y Traumatología. 2015;59(1): 19-25.[34] Amlie E, Høvik Ø, Reikerås O. Dislocation after total hip arthroplasty with 28 and 32-mm femoral head. J Orthop Traumatol. 2010;11(2): 111-115.[35] Lewinnek GE, Lewis JL, Tarr R, et al. Dislocations after total hip-replacement arthroplasties. J Bone Joint Surg Am.1978;60(2): 217.[36] Maruyama M, Feinberg JR, Capello WN, et al. The Frank Stinchfield Award: Morphologic features of the acetabulum and femur: anteversion angle and implant positioning. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;393(393): 52.[37] Dorr LD, Malik A, Dastane M, et al. Combined anteversion technique for total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(1): 119-127.[38] Mcgrory BJ, Morrey BF, Cahalan TD, et al. Effect of femoral offset on range of motion and abductor muscle strength after total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am.1995;77(6):865-869.[39] G L, MH F, R P, et al. Femoral offset: anatomical concept, definition, assessment, implications for preoperative templating and hip arthroplasty. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2009;95(3): 210.[40] Abdel MP, Cottino U, Mabry TM. Management of periprosthetic femoral fractures following total hip arthroplasty: a review. Int Orthop. 2015;39(10): 2005.[41] Lindahl H. Epidemiology of periprosthetic femur fracture around a total hip arthroplasty. Injury. 2007;38(6): 651-654.[42] Berry DJ. EPIDEMIOLOGY : Hip and Knee. Orthop Clin N Am.1999; 30(2):183-190.[43] Sidler-Maier CC, Waddell JP. Incidence and predisposing factors of periprosthetic proximal femoral fractures: a literature review. Int Orthop. 2015;39(9): 1673-1682.[44] Mallory TH. Preparation of the proximal femur in cementless total hip revision. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;(235): 47.[45] D'Antonio J, Mccarthy JC, Bargar WL, et al. Classification of femoral abnormalities in total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993; 296(296):133.[46] Weeden SH, Paprosky WG. Minimal 11-year follow-up of extensively porous-coated stems in femoral revision total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2002;17(4): 134-137.[47] Della Valle CJ, Paprosky WG. The femur in revision total hip arthroplasty evaluation and classification. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;420(420): 55-62.[48] Saleh KJ, Holtzman J, Gafni A, et al. Reliability and intraoperative validity of preoperative assessment of standardized plain radiographs in predicting bone loss at revision hip surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83(7): 1040-1046.[49] Meding JB, Ritter MA, Keating EM, et al. Impaction bone-grafting before insertion of a femoral stem with cement in revision total hip arthroplasty. A minimum two-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am.1997;79(12): 1834-1841.[50] Eldridge JD, Smith EJ, Hubble MJ, et al. Massive early subsidence following femoral impaction grafting. J Arthroplasty. 1997;12(5): 535-540.[51] Ornstein E, Atroshi I, Franzén H, et al. Early complications after one hundred and forty-four consecutive hip revisions with impacted morselized allograft bone and cement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002; 84-A(8): 1323.[52] Sierra RJ, Charity J, Tsiridis E, et al. The use of long cemented stems for femoral impaction grafting in revision total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(6): 1330-1336.[53] Ornstein E, Linder L, Ranstam J, et al. Femoral impaction bone grafting with the Exeter stem - the Swedish experience: survivorship analysis of 1305 revisions performed between 1989 and 2002. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91(4):441-446.[54] Wraighte PJ, Howard PW. Femoral impaction bone allografting with an Exeter cemented collarless, polished, tapered stem in revision hip replacement: a mean follow-up of 10.5 years. Bone Joint J.2008;90(8): 1000-1004.[55] Ghoz A, Broadhead ML, Morley J, et al. Outcomes of dual modular cementless femoral stems in revision hip arthroplasty. Orthop Rev (Pavia). 2014;6(1):5247. [56] Pellicci PM, Jr WP, Sledge CB, et al. Long-term results of revision total hip replacement. A follow-up report. J Bone Joint Surg Am.1985;67(4): 513-516.[57] Kavanagh BF, Ilstrup DM, Fitzgerald RH, Jr. Revision total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67(4): 517-526.[58] Halliday BR, English HW, Timperley AJ, et al. Femoral impaction grafting with cement in revision total hip replacement. Evolution of the technique and results. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85(6): 809-817.[59] Iorio R, Healy WL, Presutti AH. A prospective outcomes analysis of femoral component fixation in revision total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23(5): 662-669.[60] Weiss RJ, Stark A, Kärrholm J. A modular cementless stem vs. cemented long-stem prostheses in revision surgery of the hip: A population-based study from the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop. 2011;82(2): 136-142.[61] Duncan WW, Hubble MJ, Howell JR. Revision of the cemented femoral stem using a cement-in-cement technique: a five- to 15-year review. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91(5): 577-582.[62] Mounsey EJ, Williams DH, Howell JR, et al. Revision of hemiarthroplasty to total hip arthroplasty using the cement-in-cement technique. Bone Joint J. 2015;97-B(12): 1623-1627.[63] Cnudde PH, Kärrholm J, Rolfson O, et al. Cement-in-cement revision of the femoral stem: analysis of 1179 first-time revisions in the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register. Bone Joint J. 2017;99-B(4 Supple B): 27-32.[64] Rubash HE, Harris WH. Revision of nonseptic, loose, cemented femoral components using modern cementing techniques. J Arthroplasty. 1988;3(3): 241-248.[65] Collis DK. Revision total hip replacement with cement. Semin Arthroplasty. 1993;4(1): 38.[66] Izquierdo RJ, Northmoreball MD. Long-term results of revision hip arthroplasty. Survival analysis with special reference to the femoral component. J Bone Joint Surg Br.1994;76(1): 34-39.[67] Estok DM 2nd, Harris WH. Long-term results of cemented femoral revision surgery using second-generation techniques. An average 11.7-year follow-up evaluation. Clin Orthop Relat Res.1994;(299):190.[68] Katz RP, Callaghan JJ, Sullivan PM, et al. Long-term results of revision total hip arthroplasty with improved cementing technique. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997;79(2): 322-326.[69] Trumm BN, Callaghan JJ, George CA, et al. Minimum 20-year follow-up results of revision total hip arthroplasty with improved cementing technique. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(1): 236-241.[70] Solomon LB, Costi K, Kosuge D, et al. Revision total hip arthroplasty using cemented collarless double-taper femoral components at a mean follow-up of 13 years (8 to 20): an update. Bone Joint J. 2015; 97-B(8): 1038.[71] Desy NM, Johnson JD, Sierra RJ. Satisfactory results of the exeter revision femoral stem used for primary total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(2): 494.[72] Berry DJ, Harmsen WS, Ilstrup D, et al. Survivorship of uncemented proximally porous-coated femoral components. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995;(319): 168.[73] Malkani AL, Lewallen DG, Cabanela ME, et al. Femoral component revision using an uncemented, proximally coated, long-stem prosthesis. J Arthroplasty. 1996;11(4): 411-418.[74] Cameron HU. The long-term success of modular proximal fixation stems in revision total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty.2002;17(1): 138-141.[75] Mc Carthy JC, Lee JA. Complex revision total hip arthroplasty with modular stems at a mean of 14 years. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007; 465(465):166-169.[76] Bolognesi MP, Pietrobon R, Clifford PE, et al. Comparison of a hydroxyapatite-coated sleeve and a porous-coated sleeve with a modular revision hip stem. A prospective, randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A(12): 2720.[77] Adolphson PY, Salemyr MO, Sköldenberg OG, et al. Large femoral bone loss after hip revision using the uncemented proximally porous-coated Bi-Metric prosthesis. Acta Orthop. 2009;80(1): 14-19.[78] Jr EC, Jr HR, Sr EC. Distal ingrowth components. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2004, 420(420): 135-141.[79] Sporer SM, Paprosky WG. Revision total hip arthroplasty: the limits of fully coated stems. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;417(417): 203-209.[80] Moreland JR, Bernstein ML. Femoral revision hip arthroplasty with uncemented, porous-coated stems. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995; 319(319):141.[81] Krishnamurthy AB, Macdonald SJ, Paprosky WG. 5- to 13-year follow-up study on cementless femoral components in revision surgery. J Arthroplasty. 1997;12(8): 839-847.[82] Reikeras O, Gunderson RB. Excellent results with femoral revision surgery using an extensively hydroxyapatite-coated stem: 59 patients followed for 10–16 years. Acta Orthop. 2006; 77(1): 98-103.[83] Hamilton WG, Hopper RH, Cashen DV, et al. Extensively porous-coated stems for femoral revision: a choice for all seasons. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(4 Suppl 1): 106.[84] Garcia-Cimbrelo E, Garcia-Rey E, Cruz-Pardos A, et al. Stress-shielding of the proximal femur using an extensively porous-coated femoral component without allograft in revision surgery: a 5- to 17-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(10): 1363-1369.[85] Thomsen PB, Jensen NJ, Kampmann J, et al. Revision hip arthroplasty with an extensively ?porous-coated stem - excellent long-term ?results also in severe femoral bone stock loss. Hip Int. 2013;23(4): 352-358.[86] Engh CA. Extensively porous coated femoral cylinders: thirty years onward. 2015.[87] Reikerås O. Femoral revision surgery using a fully hydroxyapatite- coated stem: a cohort study of twenty two to twenty seven years. Int Orthop. 2016;41(2):271-275.[88] Böhm P, Bischel O. Femoral revision with the Wagner SL revision stem : evaluation of one hundred and twenty-nine revisions followed for a mean of 4.8 years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A(7):1023-1031.[89] Singh SP, Bhalodiya HP. Results of Wagner SL revision stem with impaction bone grafting in revision total hip arthroplasty. Indian J Orthop. 2013;47(4): 357-363.[90] Sandiford NA, Garbuz DS, Masri BA, et al. Nonmodular tapered fluted titanium stems osseointegrate reliably at short term in revision THAs. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016: 1-7.[91] Bischel OE, Böhm PM. The use of a femoral revision stem in the treatment of primary or secondary bone tumours of the proximal femur: a prospective study of 31 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(10): 1435-1441.[92] Bakt?r A, Karaaslan F, Gencer K, et al. Femoral revision using the Wagner SL revision stem: a aingle-aurgeon experience featuring 11–19 years of follow-up. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(5): 827-834.[93] Huang Y, Zhou Y, Shao H, et al. What is the difference between modular and nonmodular tapered fluted titanium stems in revision total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2017.[94] Kolb A, Grübl A, Schneckener CD, et al. Cementless total hip arthroplasty with the rectangular titanium Zweymuller stem: a concise follow-up, at a minimum of twenty years, of previous reports. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(18):1681.[95] Hartwig CH, Böhm P, Czech U, et al. The Wagner revision stem in alloarthroplasty of the hip. Arch Orthop Traum Su. 1996;115(1): 5.[96] Alamo JGD, Garcia-Cimbrelo E, Castellanos V, et al. Radiographic bone regeneration and clinical outcome with the Wagner SL revision stem: a 5-year to 12-year follow-up study. J Arthroplasty.2007;22(4): 515-524.[97] Regis D, Sandri A, Bonetti I, et al. Femoral revision with the Wagner tapered stem: a ten- to 15-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Br.2011;93(10):1320.[98] Hoberg M, Konrads C, Engelien J, et al. Outcome of a modular tapered uncemented titanium femoral stem in revision hip arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2015;39(9):1709-1713.[99] Wimmer MD, Randau TM, Deml MC, et al. Impaction grafting in the femur in cementless modular revision total hip arthroplasty: a descriptive outcome analysis of 243 cases with the MRP-TITAN revision implant.BMC Musculoskelet Disord.2013;14(1):19.[100] Wirtz DC, Gravius S, Ascherl R, et al. Uncemented femoral revision arthroplasty using a modular tapered, fluted titanium stem: 5- to 16-year results of 163 cases. Acta Orthop. 2014;85(6): 562-569.[101] Abdel MP, Cottino U, Larson DR, et al. Modular fluted tapered stems in aseptic revision total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017; 99(10): 873.[102] Wirtz DC, Heller KD, Holzwarth U, et al. A modular femoral implant for uncemented stem revision in THR. Int Orthop. 2000;24(3): 134-138.[103] Kwong LM, Miller AJ, Lubinus P. A modular distal fixation option for proximal bone loss in revision total hip arthroplasty: a 2- to 6-year follow-up study. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18(1):94-97.[104] Schuh A, Werber S, Holzwarth U, et al. Cementless modular hip revision arthroplasty using the MRP Titan Revision Stem: outcome of 79 hips after an average of 4 years’ follow-up. Arch Orthop Traum Su. 2004;124(5): 306-309.[105] Mcinnis DP, Horne G, Devane PA. Femoral revision with a fluted, tapered, modular stem seventy patients followed for a mean of 3.9 years. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(3):372-380.[106] Park YS, Moon YW, Lim SJ. Revision total hip arthroplasty using a fluted and tapered modular distal fixation stem with and without extended trochanteric osteotomy. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(7): 993.[107] Rodriguez JA, Fada R, Murphy SB, et al. Two-year to five-year follow-up of femoral defects in femoral revision treated with the link MP modular stem. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(5): 751-758.[108] Ovesen O, Emmeluth C, Hofbauer C, et al. Revision total hip arthroplasty using a modular tapered stem with distal fixation: good short-term results in 125 revisions. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(3): 348.[109] Weiss RJ, Beckman MO, Enocson A, et al. Minimum 5-year follow-up of a cementless, modular, tapered stem in hip revision arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26(1):16. |

| [1] | Zhang Tongtong, Wang Zhonghua, Wen Jie, Song Yuxin, Liu Lin. Application of three-dimensional printing model in surgical resection and reconstruction of cervical tumor [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(9): 1335-1339. |

| [2] | Zhang Yu, Tian Shaoqi, Zeng Guobo, Hu Chuan. Risk factors for myocardial infarction following primary total joint arthroplasty [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(9): 1340-1345. |

| [3] | Li Dadi, Zhu Liang, Zheng Li, Zhao Fengchao. Correlation of total knee arthroplasty efficacy with satisfaction and personality characteristics [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(9): 1346-1350. |

| [4] | Wei Wei, Li Jian, Huang Linhai, Lan Mindong, Lu Xianwei, Huang Shaodong. Factors affecting fall fear in the first movement of elderly patients after total knee or hip arthroplasty [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(9): 1351-1355. |

| [5] | Wang Jinjun, Deng Zengfa, Liu Kang, He Zhiyong, Yu Xinping, Liang Jianji, Li Chen, Guo Zhouyang. Hemostatic effect and safety of intravenous drip of tranexamic acid combined with topical application of cocktail containing tranexamic acid in total knee arthroplasty [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(9): 1356-1361. |

| [6] | Xiao Guoqing, Liu Xuanze, Yan Yuhao, Zhong Xihong. Influencing factors of knee flexion limitation after total knee arthroplasty with posterior stabilized prostheses [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(9): 1362-1367. |

| [7] | Huang Zexiao, Yang Mei, Lin Shiwei, He Heyu. Correlation between the level of serum n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and quadriceps weakness in the early stage after total knee arthroplasty [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(9): 1375-1380. |

| [8] | Zhang Chong, Liu Zhiang, Yao Shuaihui, Gao Junsheng, Jiang Yan, Zhang Lu. Safety and effectiveness of topical application of tranexamic acid to reduce drainage of elderly femoral neck fractures after total hip arthroplasty [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(9): 1381-1386. |

| [9] | Yuan Jiawei, Zhang Haitao, Jie Ke, Cao Houran, Zeng Yirong. Underlying targets and mechanism of Taohong Siwu Decoction in prosthetic joint infection on network pharmacology [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(9): 1428-1433. |

| [10] | Chen Junming, Yue Chen, He Peilin, Zhang Juntao, Sun Moyuan, Liu Youwen. Hip arthroplasty versus proximal femoral nail antirotation for intertrochanteric fractures in older adults: a meta-analysis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(9): 1452-1457. |

| [11] | Zeng Yanhua, Hao Yanlei. In vitro culture and purification of Schwann cells: a systematic review [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 1135-1141. |

| [12] | Zhao Zhongyi, Li Yongzhen, Chen Feng, Ji Aiyu. Comparison of total knee arthroplasty and unicompartmental knee arthroplasty in treatment of traumatic osteoarthritis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(6): 854-859. |

| [13] | Liu Shaohua, Zhou Guanming, Chen Xicong, Xiao Keming, Cai Jian, Liu Xiaofang. Influence of anterior cruciate ligament defect on the mid-term outcome of fixed-bearing unicompartmental knee arthroplasty [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(6): 860-865. |

| [14] | Zhang Nianjun, Chen Ru. Analgesic effect of cocktail therapy combined with femoral nerve block on total knee arthroplasty [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(6): 866-872. |

| [15] | Yuan Jun, Yang Jiafu. Hemostatic effect of topical tranexamic acid infiltration in cementless total knee arthroplasty [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(6): 873-877. |

| Viewed | ||||||

|

Full text |

|

|||||

|

Abstract |

|

|||||