• 组织构建基础实验 basic experiments in tissue construction • 上一篇 下一篇

计算机三维重构验证Dystrophin疏水区段与Duchenne型肌营养不良的发病

梁颖茵1,操基清1,杨 娟2,张 成1

- 1中山大学附属第一医院,广东省广州市 510000;2南方医科大学珠江医院神经内科,广东省广州市 510000

-

修回日期:2013-11-15出版日期:2013-12-10发布日期:2013-12-10 -

通讯作者:张成,博士,博士生导师,教授,中山大学附属第一医院神经内科 ,广东省广州市 510700 -

作者简介:梁颖茵☆,中山大学在读博士,主治医师,主要从事神经遗传及肌肉病方面的研究。 共同第一作者:操基清,中山大学在读博士,主要从事神经内科方面的研究。 共同第一作者:杨娟,主要从事神经内科方面的研究。

Effects of the dystrophin hydrophobic regions in the pathogenesis of Duchenne muscular dystrophy A three-dimensional reconstruction verification

Liang Ying-yin1, Cao Ji-qing1, Yang Juan2, Zhang Cheng1

- 1 The First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou 510000, Guangdong Province, China

2 Department of Neurology, Zhujiang Hospital of Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510000, Guangdong Province, China

-

Revised:2013-11-15Online:2013-12-10Published:2013-12-10 -

Contact:Zhang Cheng, M.D., Doctoral supervisor, Professor, the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou 510000, Guangdong Province, China chengzhang100@hotmail.com -

About author:Liang Ying-yin☆, Studying for doctorate, Attending physician, the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou 510000, Guangdong Province, China liangyingyin@hotmail.com Cao Ji-qing, Studying for doctorate, the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou 510000, Guangdong Province, China Yang Juan, Department of Neurology, Zhujiang Hospital of Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510000, Guangdong Province, China

摘要:

背景:Duchenne型肌营养不良和Becker型进行性肌营养不良都是dystrophin基因突变所致,但后者临床表型较轻。“阅读框规则”可解释大部分基因型与临床型关系,但累及疏水区段的整码突变也可导致Duchenne型肌营养不良。因此很有必要了解疏水区域在dystrophin中的功能,且这些疏水区段的三维结构及功能在发病机制中所起的具体作用仍未阐明。 目的:通过Kyte&Doolittle平均疏水轮廓分析研究dystrophin的疏水区段。利用swiss-model三维重构dystrophin的疏水区段阐述其在发病机制中所起的作用。 方法:参考莱顿开放数据库(http://www.dmd.nl/)及收集中山大学附属第一医院2002年至2013年确诊Duchenne型进行性肌营养不良或Becker型进行性肌营养不良的缺失型整码突变患者资料共1 038例,分析其临床型与基因型关系。使用bioedit软件计算dystrophin的平均疏水轮廓及利用swiss-model三维重构疏水区段,结合临床型和基因型关系确定dystrophin重要功能区。 结果与结论:dystrophin存在4个疏水区段,分别为肌动蛋白结合区内的Calponin同源区2、中央棒区内的重复区16、第三铰链区和EF手型区。第1,2,4疏水区段是dystrophin糖蛋白复合物中dystrophin与其他糖蛋白的结合区域,其破坏严重影响dystrophin糖蛋白复合物功能,临床症状重。中央棒区在第三铰链区附近断裂后,HⅢ的无规则卷结构不容易与断端重复区的螺旋结构恢复连接。但第三铰链区同时缺失,其两端的重复区较容易重新连接,所以第3疏水区破坏后其临床症状反而较轻。提示dystrophin的疏水区段是其重要功能区,多是dystrophin糖蛋白复合物中dystrophin与相关蛋白的结合部位,在Duchenne型肌营养不良的发病机制中起重要作用。

中图分类号:

引用本文

梁颖茵,操基清,杨 娟,张 成. 计算机三维重构验证Dystrophin疏水区段与Duchenne型肌营养不良的发病[J]. 中国组织工程研究, doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-4344.2013.50.014.

Liang Ying-yin, Cao Ji-qing, Yang Juan, Zhang Cheng. Effects of the dystrophin hydrophobic regions in the pathogenesis of Duchenne muscular dystrophy A three-dimensional reconstruction verification[J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-4344.2013.50.014.

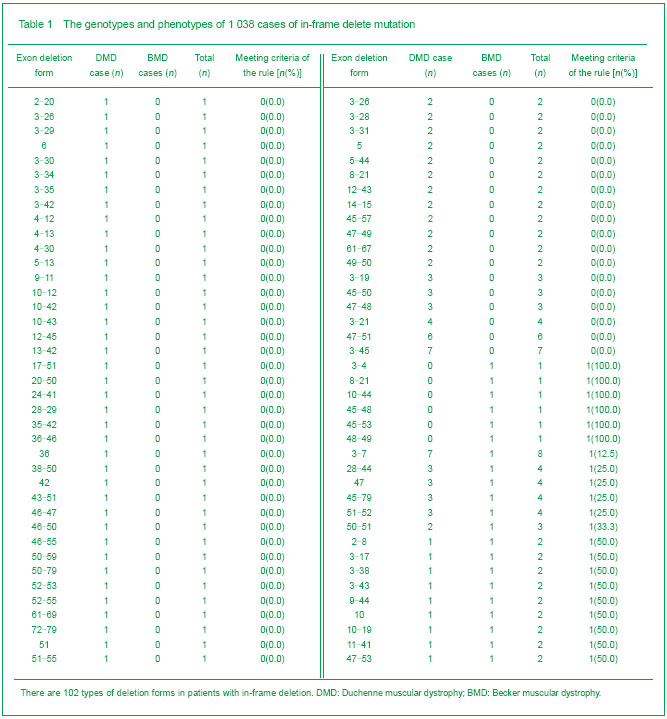

796 of 1 038 cases met the criteria of the reading-frame rule, accounting for 76.7%. In the rest 242 cases (23.3%), 102 types of deletion forms were identified (Table 1).

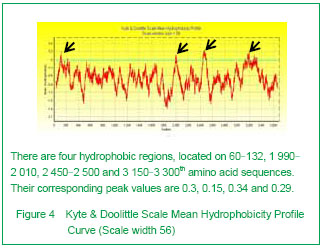

Kyte & Doolittle curve showed there were four hydrophobic regions on dystrophin, relatively located on 60-132, 1 990-2 010, 2 450-2 500 and 3 150-3 300th amino acid sequences. They were coded by 3-6, 42, 51, 65-68 exons, respectively. Their corresponding peak values were 0.3, 0.15, 0.34 and 0.29. The 3rd hydrophobic region owned the highest peak value (Figure 4).

In all 1 038 cases, 714 cases (68.8%) had integrated hydrophobic regions; the rest 324 cases (31.2%) belonged to the deletion forms (Table 2). In the group with integrated hydrophobic regions, there were 104 cases of DMD (14.6%) and 610 cases of BMD (85.4%).

In the deletion form group, there were 137 cases of DMD (42.3%) and 187 of BMD (57.7%). The proportion of DMD in two groups (cases who did not met the criteria of the reading frame rule) had a significantly statistical difference (P < 0.001). As seen from Table 2, BMD was more common in the integrated hydrophobic region groups and the 3rd region involvement alone than DMD. In other involved hydrophobic regions, DMD incidence was higher than that of BMD.

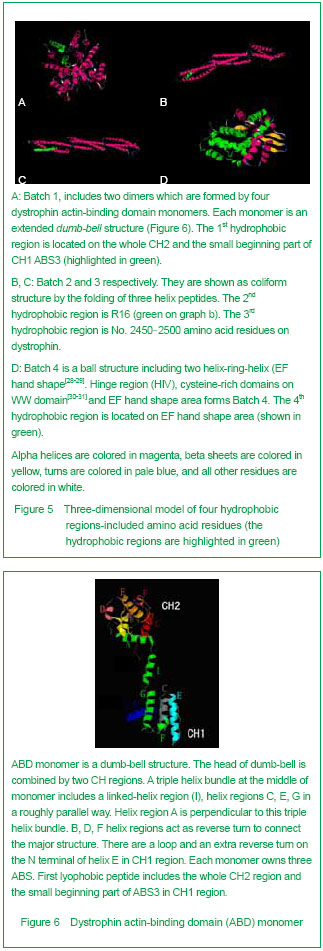

3D Swiss-modeling for the dystrophin hydrophobic regions By using Swiss-model, a homology structure was forecasted on the important domains of dystrophin. Four hydrophobic regions were separately included in the amino acid residues coded as 9-246, 2 001-2 307, 2 471-2 801, 3 047-3 306, as demonstrated by the 3D predicted model. They were named as Batches 1-4 respectively. All the 3D-models were showed and analyzed in Rasmol software (Figure 5).

| [1] Pane M, Lombardo ME, Alfieri P, et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and cognitive function in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: phenotype-genotype correlation. J Pediatr. 2012;161(4):705-709.e1.[2] Magri F, Govoni A, D'Angelo MG, et al. Genotype and phenotype characterization in a large dystrophinopathic cohort with extended follow-up. J Neurol. 2011;258(9): 1610-1623.[3] Escolar DM, Zimmerman A, Bertorini T, et al. Pentoxifylline as a rescue treatment for DMD: a randomized double-blind clinical trial. Neurology. 2012;78(12):904-913. [4] López-Hernández LB, van Heusden D, Soriano-Ursúa MA, et al. Genotype-phenotype discordance in a Duchenne muscular dystrophy patient due to a novel mutation: insights into the shock absorber function of dystrophin. Rev Neurol. 2011;52(12):720-724.[5] Bushby K, Connor E. Clinical outcome measures for trials in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: report from International Working Group meetings. Clin Investig (Lond). 2011;1(9): 1217-1235.[6] Scully MA, Cwik VA, Marshall BC, et al. Can outcomes in Duchenne muscular dystrophy be improved by public reporting of data? Neurology. 2013;80(6):583-589. [7] Soltanzadeh P, Friez MJ, Dunn D, et al. Clinical and genetic characterization of manifesting carriers of DMD mutations. Neuromuscul Disord. 2010;20(8):499-504. [8] Basumatary LJ, Das M, Goswami M, et al. Deletion pattern in the dystrophin gene in Duchenne muscular dystrophy patients in northeast India. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2013; 4(2):227-229. [9] Moore CJ, Winder SJ. The inside and out of dystroglycan post-translational modification. Neuromuscul Disord. 2012; 22(11):959-965. [10] Janke A, Upadhaya R, Snow WM, et al. A new look at cytoskeletal NOS-1 and β-dystroglycan changes in developing muscle and brain in control and mdx dystrophic mice. Dev Dyn. 2013. in press.[11] Kalman L, Leonard J, Gerry N, et al. Quality assurance for Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy genetic testing: development of a genomic DNA reference material panel. J Mol Diagn. 2011;13(2):167-174. [12] Rani AQ, Sasongko TH, Sulong S, et al. Mutation spectrum of dystrophin gene in malaysian patients with Duchenne/Becker muscular dystrophy. J Neurogenet. 2013;27(1-2):11-15.[13] Lee BL, Nam SH, Lee JH, et al. Genetic analysis of dystrophin gene for affected male and female carriers with Duchenne/Becker muscular dystrophy in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2012;27(3):274-280. [14] de Brouwer AP, Nabuurs SB, Verhaart IE, et al. A 3-base pair deletion, c.9711_9713del, in DMD results in intellectual disability without muscular dystrophy. Eur J Hum Genet. 2013. in press.[15] Kesari A, Pirra LN, Bremadesam L, et al. Integrated DNA, cDNA, and protein studies in Becker muscular dystrophy show high exception to the reading frame rule. Hum Mutat. 2008;29(5):728-737. [16] Zhang D, Cui S, Guo H, et al. Genomic structure, characterization and expression analysis of a manganese superoxide dismutase from pearl oyster Pinctada fucata. Dev Comp Immunol. 2013;41(4):484-490. [17] Yang J, Li SY, Li YQ, et al. MLPA-based genotype-phenotype analysis in 1053 Chinese patients with DMD/BMD. BMC Med Genet. 2013;14:29. [18] Tuffery-Giraud S, Béroud C, Leturcq F, et al. Genotype-phenotype analysis in 2,405 patients with a dystrophinopathy using the UMD-DMD database: a model of nationwide knowledgebase. Hum Mutat. 2009;30(6): 934-945. [19] Kyte J, Doolittle RF. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J Mol Biol. 1982;157(1): 105-132.[20] Ghose S, Tao Y, Conley L, et al. Purification of monoclonal antibodies by hydrophobic interaction chromatography under no-salt conditions. MAbs. 2013;5(5):795-800. [21] Fokkema IF, den Dunnen JT, Taschner PE. LOVD: easy creation of a locus-specific sequence variation database using an "LSDB-in-a-box" approach. Hum Mutat. 2005;26(2):63-68.[22] Fokkema IF, Taschner PE, Schaafsma GC, et al. LOVD v.2.0: the next generation in gene variant databases. Hum Mutat. 2011;32(5):557-563. [23] Bushby KM, Gardner-Medwin D. The clinical, genetic and dystrophin characteristics of Becker muscular dystrophy. I. Natural history. J Neurol. 1993;240(2):98-104.[24] Norwood FL, Sutherland-Smith AJ, Keep NH, et al. The structure of the N-terminal actin-binding domain of human dystrophin and how mutations in this domain may cause Duchenne or Becker muscular dystrophy. Structure. 2000; 8(5):481-491.[25] Zhang C, Cai JH, Liu ZL, et al. The relationship between dystrophin hydrophobic structure and DMD/BMD. Zhongshan Yike Daxue Xuebao. 1993;14(2):160. [26] Kiefer F, Arnold K, Künzli M, et al. The SWISS-MODEL Repository and associated resources. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Database issue):D387-392. [27] Goodsell DS. Representing structural information with RasMol. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2005;Chapter 5:Unit 5.4.[28] Kretsinger RH, Nockolds CE. Carp muscle calcium-binding protein. II. Structure determination and general description. J Biol Chem. 1973;248(9):3313-3326.[29] Heidarsson PO, Otazo MR, Bellucci L, et al. Single-Molecule Folding Mechanism of an EF-Hand Neuronal Calcium Sensor. Structure. 2013;21(10):1812-1821. [30] Bork P, Sudol M. The WW domain: a signalling site in dystrophin? Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;19(12):531-533.[31] Hiraki T, Abe F. Overexpression of Sna3 stabilizes tryptophan permease Tat2, potentially competing for the WW domain of Rsp5 ubiquitin ligase with its binding protein Bul1. FEBS Lett. 2010;584(1):55-60. [32] Koenig M, Monaco AP, Kunkel LM. The complete sequence of dystrophin predicts a rod-shaped cytoskeletal protein. Cell. 1988;53(2):219-228.[33] Gumerson JD, Michele DE. The dystrophin-glycoprotein complex in the prevention of muscle damage. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:210797.[34] Mondal J, Morrone JA, Berne BJ. How hydrophobic drying forces impact the kinetics of molecular recognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(33):13277-13282.[35] Norwood FL, Sutherland-Smith AJ, Keep NH, et al. The structure of the N-terminal actin-binding domain of human dystrophin and how mutations in this domain may cause Duchenne or Becker muscular dystrophy. Structure. 2000; 8(5): 481-491.[36] Singh SM, Mallela KM. The N-terminal actin-binding tandem calponin-homology (CH) domain of dystrophin is in a closed conformation in solution and when bound to F-actin. Biophys J. 2012;103(9):1970-1978. [37] Legrand B, Giudice E, Nicolas A, et al. Computational study of the human dystrophin repeats: interaction properties and molecular dynamics. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e23819. [38] Acsadi G, Moore SA, Chéron A, et al. Novel mutation in spectrin-like repeat 1 of dystrophin central domain causes protein misfolding and mild Becker muscular dystrophy. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(22):18153-18162.[39] Mirza A, Menhart N. Stability of dystrophin STR fragments in relation to junction helicity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008; 1784(9):1301-1309.[40] Lai Y, Zhao J, Yue Y, et al. α2 and α3 helices of dystrophin R16 and R17 frame a microdomain in the α1 helix of dystrophin R17 for neuronal NOS binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(2):525-530. [41] Harper SQ. Molecular dissection of dystrophin identifies the docking site for nNOS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013; 110(2):387-388. [42] Cazzella V, Martone J, Pinnarò C, et al. Exon 45 skipping through U1-snRNA antisense molecules recovers the Dys-nNOS pathway and muscle differentiation in human DMD myoblasts. Mol Ther. 2012;20(11):2134-2142. [43] Sahni N, Mangat K, Le Rumeur E, et al. Exon edited dystrophin rods in the hinge 3 region. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1824(10):1080-1089. [44] Banks GB, Judge LM, Allen JM, et al. The polyproline site in hinge 2 influences the functional capacity of truncated dystrophins. PLoS Genet. 2010;6(5):e1000958.[45] Carsana A, Frisso G, Tremolaterra MR, et al. Analysis of dystrophin gene deletions indicates that the hinge III region of the protein correlates with disease severity. Ann Hum Genet. 2005;69(Pt 3):253-259. [46] Nicholson LV, Johnson MA, Bushby KM, et al. Integrated study of 100 patients with Xp21 linked muscular dystrophy using clinical, genetic, immunochemical, and histopathological data. Part 2. Correlations within individual patients. J Med Genet. 1993;30(9):737-744.[47] Stahelin RV. Lipid binding domains: more than simple lipid effectors. J Lipid Res. 2009;50 Suppl:S299-304. [48] Aoki Y, Nakamura A, Yokota T, et al. In-frame dystrophin following exon 51-skipping improves muscle pathology and function in the exon 52-deficient mdx mouse. Mol Ther. 2010;18(11):1995-2005. [49] Chung W, Campanelli JT. WW and EF hand domains of dystrophin-family proteins mediate dystroglycan binding. Mol Cell Biol Res Commun. 1999;2(3):162-171.[50] Hnia K, Zouiten D, Cantel S, et al. ZZ domain of dystrophin and utrophin: topology and mapping of a beta-dystroglycan interaction site. Biochem J. 2007;401(3):667-677. [51] Huang X, Poy F, Zhang R, et al. Structure of a WW domain containing fragment of dystrophin in complex with beta-dystroglycan. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7(8):634-638.[52] Constantin B. Dystrophin complex functions as a scaffold for signalling proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013. in press.[53] Cirak S, Feng L, Anthony K, et al. Restoration of the dystrophin-associated glycoprotein complex after exon skipping therapy in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Mol Ther. 2012;20(2):462-467. [54] R Mendell J, Rodino-Klapac LR, Sahenk Z, et al. Eteplirsen for the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Ann Neurol. 2013. in press. |

| [1] | 许国峰, 李学斌, 唐一钒, 赵 寅, 周盛源, 陈雄生, 贾连顺. 人黄韧带细胞骨化发生过程中的自噬[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2020, 24(8): 1174-1181. |

| [2] | 周 玉, 龙小安, 李 宁, 王 纯. 有限元法分析髌腱炎状态时的生物力学变化[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2020, 24(8): 1280-1286. |

| [3] | 宋旭东, 何云武, 李勇霖, 陈 静, 胡君兰. 超声引导下椎旁神经阻滞治疗带状疱疹相关疼痛的Meta分析[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2020, 24(11): 1797-1804. |

| [4] | 曹 曦,崔 伟,陈跃平,冯 洋,路 通. 尼尔样1型生长因子促进修复骨再生和治疗骨质疏松的应用潜力[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2019, 23(8): 1235-1240. |

| [5] | 庞巨涛,张新虎,孙建华,周连军,刘 斌,李凤国,李文哲. 经皮球囊扩张椎体后凸成形后椎体再骨折的危险:回顾性多因素分析[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2019, 23(8): 1182-1187. |

| [6] | 宋 超,田 鑫,刘 琳,徐雅雯,孟 圆,李晓丽,彭 萌,李华东,王志涛,戈 莎. 骨密度测试联合老年人运动功能量表-25评估筛查老年人基础运动障碍及跌倒风险:天津市6个社区1 458例调查[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2019, 23(7): 990-995. |

| [7] | 艾力麦尔旦•艾尼瓦尔,李 鹏,刁兆峰,木合塔尔•霍加. 幼兔颅盖骨成骨细胞的分离培养及鉴定[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2019, 23(7): 996-1000. |

| [8] | 武 敏1,李 雪1,高 洁1,杨 帅1,蔡毅志2,王明国1 . 下颌持续前导对成年及幼年期大鼠髁突软骨血管内皮生长因子表达和Micro-CT下髁突骨质变化的差异[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2019, 23(7): 1001-1006. |

| [9] | 王灿莉,焦志立,孙 勇,孙 嵩. 两种富血小板纤维蛋白对人牙龈成纤维细胞增殖活性影响的比较[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2019, 23(7): 1007-1012. |

| [10] | 周艳星,彭新生,侯 敢,李江滨,张 华,周志昆,周艳芳. 辣椒素抑制成纤维细胞增殖的作用及其分子机制[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2019, 23(7): 1018-1022. |

| [11] | 赵彩萍,朱美玲,王婷婷,柳雪蕾,刘翠玲. 化学神经根炎症模型大鼠的制备及评价[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2019, 23(7): 1030-1034. |

| [12] | 韩 杰,陈跃平,莫 坚,王大伟,苏 波,李书振,夏 天,王世鑫 . 三七总皂苷干预激素性股骨头缺血坏死模型兔的超微结构评价[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2019, 23(7): 1035-1039. |

| [13] | 黄 红,黄佳纯,黄宏兴,王吉利,刘少津,汪悦东 . 过表达雌激素相关受体α干预沉默Bak1、Bcl2重组腺病毒载体转染MG63细胞的增殖与分化[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2019, 23(7): 1041-1045. |

| [14] | 彭显江,刘勃志,段海峰,杨谦梓,胡 胜 . 小尾寒羊主动脉瓣及二尖瓣置换过程中的麻醉管理[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2019, 23(7): 1052-1056. |

| [15] | 杨淳贺,仉 红,董 明,王丽娜,牛卫东. 野生型小鼠慢性根尖周炎模型PLCγ2的表达[J]. 中国组织工程研究, 2019, 23(7): 1057-1062. |

walking ability even after 15. Both DMD and BMD are due to the mutation of the same gene sequence but have obvious differences on the severity of disease. The former is considered as a fatal genetic disorder while the latter is of longer life span and better life quality[4-7]. DMD and BMD are caused by the gene mutation of dystrophin which is a cytoskeleton protein and its gene is located on Xp21.1[8]. Dystrophin is a large cytoskeleton protein with molecular mass of 427 kDa. It is composed of N-terminal region, central rob domain, C-terminal region. The N-terminal region of dystrophin binds the actin. The large central rob domain comprises 24 spectrin-like repeats and 4 hinges, and another actin binding side and a nNOS binding side are found in central rob dmain. The C-terminal region binds the dystrobrevins, syntrophins and β-dystroglycan, a transmembrane glycoprotein, which have interaction with sarcoglycans and α-dystroglycan. Furthermore, α-dystroglycan has interaction with laminin-2. That is to say, the membrane-spanning dystrophin glycoprotein complex (DGC) act as an indirect linkage between the actin-based cytoskeleton and the extracellular matrix[9-10]. DMD gene is the largest gene in human being. There are 79 exons in it and various mutation types are found in the gene, 65% are deletion, 7% to 10% are duplication, 25% to 30% are point mutation[11-14]. Out-of-frame mutation can interrupt the open reading frame (ORF) so that the transcription is terminated. Therefore the dystrophin production is not sufficient to elicit the function. In-frame mutation did not destroy ORF and thus dystrophin is shortened only and its partial function remains. General speaking out-of-frame mutation causes DMD while in-frame mutation results in BMD; this is termed as “reading-frame rule”[15-16]. However, some in-frame mutations can also cause DMD[17], which is hard to explain by this rule. Also, this kind of situation indicates the sequence location where has mutation will have important influences on the structure and function of in-frame mutation[18]. This aim of study is by investigating the Kate & Doolittle mean scale hydrophobicity profile[19-20], to indentify the important functional domains of dystrophin and to constitute its structure in a three-dimensional (3D) model. Their structure and functions will be analyzed as well as the pathogenesis mechanism when they are destroyed. By this way, supplemental information is provided to explain the reading-frame rule.

Design

.jpg)

.jpg)

1实验设计构思介绍:

| 阅读次数 | ||||||

|

全文 |

|

|||||

|

摘要 |

|

|||||