Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research ›› 2018, Vol. 22 ›› Issue (13): 2126-2132.doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-4344.0429

Dental pulp stem cells in tissue engineering: application and development

Shao Miao-miao1, Liu Zhong-xi1, Xu Nuo2, Liu Qing-hua1, Wang Dong1, He Jian-ya1, Li Xiao-jie1

- 1School of Stomatology, Dalian Medical University, Dalian 116044, Liaoning Province, China; 2Zhongshan College of Dalian Medical University, Dalian 116000, Liaoning Province, China

-

Online:2018-05-08Published:2018-05-08 -

Contact:Li Xiao-jie, Master, Associate professor, School of Stomatology, Dalian Medical University, Dalian 116044, Liaoning Province, China -

About author:Shao Miao-miao, Studying for master’s degree, School of Stomatology, Dalian Medical University, Dalian 116044, Liaoning Province, China. Liu Zhong-xi, Studying for master’s degree, School of Stomatology, Dalian Medical University, Dalian 116044, Liaoning Province, China. Shao Miao-miao and Liu Zhong-xi contributed equally to this work. -

Supported by:the Project of Liaoning Provincial Department of Science and Technology, No. 201602230

CLC Number:

Cite this article

Shao Miao-miao, Liu Zhong-xi, Xu Nuo, Liu Qing-hua, Wang Dong, He Jian-ya, Li Xiao-jie. Dental pulp stem cells in tissue engineering: application and development[J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2018, 22(13): 2126-2132.

share this article

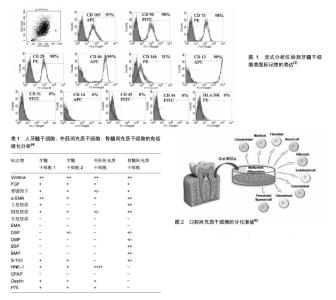

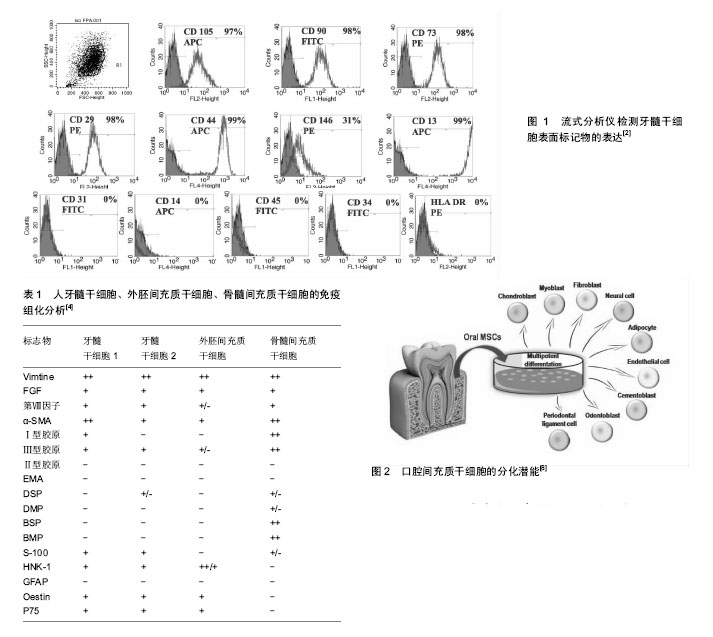

2.1 牙髓干细胞的定义 牙髓干细胞是起源于神经脊细胞的自体组织细胞。Gronthos等于2000年首次分离并命名了牙髓干细胞,与骨髓间充质干细胞类似,牙髓干细胞中CD105,CD90,CD70等标记物表达阳性,CD34,CD45,CD31,CD14,HLA-DR等造血细胞标记物阴性(图1)。然而牙髓干细胞也有其独特之处[1-2],2003年,Shi与Gronthos证实,大多数牙髓干细胞都可以表达膜细胞的标志物3G5,而骨髓间充质干细胞则很少表达[3]。王亦菁等[4]通过免疫组化方法研究牙髓干细胞的细胞表型,结果显示除了表达成纤维细胞的标志波形丝蛋白、成纤维细胞生长因子,还表达内皮细胞相关标志如VCAM-1、第Ⅷ因子,平滑肌标志如平滑肌动蛋白,骨标志如Ⅰ型胶原、Ⅲ型胶原、骨桥素等。牙髓干细胞对软骨标志Ⅱ型胶原和上皮细胞标志EMA不表达。牙髓干细胞表型的多样性及表达强弱的差异表明牙髓干细胞克隆株的不均一性,它可能是由处于分化和发育不同阶段的细胞组成(表1)。2011年,Karaoz等[5]为了更进一步区分上述两种干细胞,将骨髓间充质干细胞定义为骨髓来源的间充质干细胞,他们认为牙髓干细胞有内在的神经胶质的特性,在体外既可以分化成神经细胞,也可以分化成血管内皮细胞。 2.2 牙髓干细胞来源和分离培养 2.2.1 牙髓干细胞来源 牙髓干细胞取材容易,来源广泛,主要是从临床废弃和拔除的牙齿中获取,其中第三磨牙是主要来源。其次正畸治疗所需的减数牙和感染的牙髓也是潜在的组织应用来源[1,6]。已有研究报道,从冠折牙中获取牙髓干细胞也是一种简单易行的方法。当患者有不可逆性牙髓炎时,临床医生往往会采用牙髓摘除术治疗受损的患牙,研究表明,炎症牙髓中也有牙髓干细胞,且性能与正常牙髓中提取的牙髓干细胞无差别。尽管感染牙髓来源的牙髓干细胞中Stro-1+细胞比例及成骨分化能力与后者相比无显著差异,但潜在的致病原仍可能限制其在组织工程中的应用。Miura等在2003年也从儿童脱落的乳牙牙髓中成功提取了牙髓干细胞。牙髓干细胞不仅能从人类牙髓中提取,从鼠、犬、猪、羊,兔、猩猩、恒河猴等其他物种中也能提取[7]。 2.2.2 牙髓干细胞分离与储存 牙髓干细胞可以用不同的方法进行筛选,如高增殖潜能、各种表面标记物和核染色的高通量荧光。尽管不同牙髓干细胞的标志物可能不同,但分离所得的细胞都具有多向分化能力。 Gronthos等根据牙髓干细胞的高增殖潜能首次提取出牙髓干细胞,之后他们将牙髓细胞分成单个细胞,提取出生长率最高的克隆群体。虽然牙髓干细胞增殖速度很快,但是传代频繁且接种密度极低的情况下,牙髓干细胞仅仅表现其多向分化潜能。基于细胞表面标志物使用流式细胞术或抗体共轭表面标志的微珠也能分离特异性细胞。Kawashima[7]在2012年的一篇综述中系统描述了牙髓干细胞中潜在的生物标志物,并讨论了它们神经脊的来源,包括STRO-1,CD29,CD44,CD73,CD90,CD105,CD146,CD166,CD271。利用干细胞具有排出Hoechst染料33342的能力,可以从牙髓组织中提取干细胞,它可以分化为成骨细胞、软骨细胞、脂肪细胞和神经元细胞(图2)[8]。 组织块法或者酶消化法是分离牙髓干细胞的有效方法[6]。酶消化法所得的牙髓干细胞克隆形成率及增殖能力优于组织块法。牙髓中克隆形成细胞率明显高于骨髓中间质细胞形成率。牙髓干细胞在传代80-100次后仍然具有高增殖、高分化的潜能[9-10]。冷冻保存是现在常用的储存牙髓干细胞的方法,但是费时又昂贵。Takebe等[11]开发了新型冷冻保存方法(NCM),冷冻的牙髓组织解冻后仍适用于牙髓干细胞的提取。他们评估了从冷冻牙髓组织提取的牙髓干细胞(DPSCs-NCM)和不用冷冻储存即外植方法(DPSCs-C)获得的牙髓干细胞的细胞属性,发现两者的增殖能力无差别。流式细胞仪分析表明,二者都在相同水平上表达间充质干细胞的特性,且都不表达造血细胞标志物。此外,二者在不同的诱导培养基中都可以分化为成骨细胞、软骨细胞和成脂细胞。因此,新型冷冻保存方法可能会降低冷冻保存牙髓干细胞的成本,从而为牙髓干细胞适用于以细胞为基础的组织疗法提供更好的理论基础。 2.3 牙髓干细胞在组织工程领域的应用 2.3.1 牙组织和牙周组织再生领域 牙齿或牙列缺失是口腔疾病的头号杀手,义齿修复和种植牙是目前临床上的主要解决方案。牙髓干细胞被广泛认定是牙组织工程领域最有潜力的干细胞,通过干细胞疗法实现牙齿再生有希望治疗牙齿缺损和牙齿缺失。牙齿组织工程是将牙齿来源干细胞接种于组织工程支架上,辅以促进牙齿发育的生长因子或组织液,实现牙齿的再生或牙列的修复[12-16]。Ronthos等将人的第三磨牙牙髓组织行原代培养,分离牙髓干细胞并将其置于含矿化液的培养液中,待形成矿化结节后将其与羟磷灰石-磷酸三钙支架复合,再将其移植到免疫缺陷小鼠的背部皮下,6周后内衬成牙本质细胞样细胞的牙本质样结构环绕在牙髓样组织周围形成牙本质牙髓样复合体。Liu等[17]研究表明,不同浓度的β-甘油磷酸盐可以调节牙髓干细胞向成牙本质细胞分化。郑丽珠等[18]实验结果表明壳聚糖-纤维蛋白原复合支架材料有利于牙髓干细胞的增殖与黏附,可为临床治疗年轻恒牙牙髓感染及外伤等提供基础性的研究依据。研究者们已证实牙髓干细胞在体外经诱导后可以分化为成牙本质样细胞,而且在体内可以形成牙髓牙本质复合体样结构,是牙髓组织中最具有应用潜能的组织化活性细胞,可与生物材料有效的结合,在牙髓牙本质复合体再生及牙再生中具有广泛的应用前景[19-21]。这些研究发现为牙髓干细胞在牙齿组织工程的应用奠定了理论依据。 牙周疾病是一种慢性感染性疾病,也是导致缺牙的另一主要原因,疾病发展的后期往往伴有牙槽骨吸收等牙周组织的严重破坏。牙周组织工程指利用合适的再生细胞,以合适的支架为平台,在信号分子的辅助下实现功能性牙周组织的再生。牙周韧带干细胞是牙齿组织工程中另一个生物工程干细胞。Ding等[22-23]用同种异体牙髓干细胞和牙周韧带干细胞实现了治疗小型猪牙周炎的技术过程。生长因子和形态因子是牙周组织工程中必不可少的组分,二者主要用来提高干细胞的增殖和分化能力,同时刺激干细胞的合成和分泌矿物基质。多种生长因子已被成功证实可以支持牙周再生,例如牙釉质基质衍生物。它所包含的低分子量蛋白质能吸收牙根表面的羟基磷灰石和胶原纤维,诱导牙骨质形成和牙周组织的再生。 牙槽骨吸收是口腔医学面临的棘手问题,牙槽骨的吸收是缓慢进行性的,也具有一定破坏性和不可逆性,因此实现牙槽骨的再生至关重要。D’Aquino等[24]从无用的第三磨牙中提取牙髓干细胞,并利用胶原海绵支架,发现可以修复第二磨牙远端牙槽嵴的骨吸收。影像学评估显示在3个月后有大量新生的层状样骨形成,同时邻近的第二磨牙也有较多的附着形成。3年之后,再生组织完全形成密质骨,这是一项具有突破性的发现[25]。Brunelli等[26]试图利用牙髓干细胞完成窦道的改建,进行了为期4个月的实验,发现骨形成越来越多。牙科植入物表面的粗糙度能影响成人骨髓间充质干细胞的增殖和分化。Iaculli等[27]发现,经特殊处理的钛种植体表面可以通过调控microRNA的表达加速人类牙髓干细胞的骨整合过程,且离子喷砂和酸蚀处理表面似乎对成骨细胞的生长影响显著,这一发现对临床疗效的改善和增强具有一定的意义。 牙髓干细胞既能使牙髓-牙本质复合体再生从而修复受损牙髓,也可以构建组织工程牙和牙周组织,为牙组织和牙周组织再生带来新前景。牙髓干细胞有望在今后成为一种安全有效的治疗手段,为缺牙患者带来福音,对于改善患者的生活质量有重大的指导作用。 2.3.2 骨组织再生领域 体内研究显示,牙髓干细胞具有成骨细胞的潜能。体外研究表明,牙髓干细胞接种于明胶支架能异位形成骨结构,骨组织来源的种子细胞作为特殊的干细胞来源,为骨组织工程开辟新路径。 Yuan等[28]探讨SOX2对牙髓干细胞成骨分化的影响,并开发了一种新的方法促进牙髓干细胞成骨分化。通过反转录病毒建立了过表达SOX2的牙髓干细胞。结果表明,SOX2 通过调节成骨基因和骨形态发生蛋白家族促进牙髓干细胞向成骨细胞分化。牙髓干细胞在骨组织的应用同样离不开许多新型的组织工程材料。Xia等[29]利用一种含金纳米颗粒(GNP)的新型磷酸粘结剂(GNP-CPC),对人类牙髓干细胞的成骨诱导能力进行了研究。含金纳米颗粒的结合改善了牙髓干细胞在磷酸粘结剂上的行为,提高细胞的黏附和增殖以及成骨分化能力(14 d内增加2至3倍)。Paduano等[30]评估了牙髓干细胞在水凝胶支架和胶原蛋白Ⅰ支架上的成牙成骨分化水平,水凝胶支架来源于骨细胞外基质,而胶原蛋白Ⅰ支架是牙髓细胞外基质的主要成分之一。通过一系列的实验方法验证,结果显示,当牙髓干细胞在水凝胶支架上培养时,DSPP,DMP-1和MEPE基因的mRNA表达水平显著上调,与在胶原蛋白Ⅰ支架上培养差异有显著性意义。此外,生长因子或促成骨(成牙)培养基添加也会进一步上调DSPP,DMP-1和MEPE基因的mRNA表达水平,这些结果证实了水凝胶支架诱导牙髓干细胞成骨成牙分化的潜能。随着研究的深入,体外重建骨组织缺损逐渐成为可能,这对于增加患者预后疗效,改善患者的生活质量有很大的意义。 2.3.3 神经修复 近年来,牙髓干细胞在神经系统疾病的应用也受到极大的关注。移植来源于人类乳牙牙髓的间充质干细胞能有效帮助神经损伤的恢复[31]。Matsubara等[32]将收集的乳牙牙髓干细胞的条件培养液在急性损伤后期鞘内注射到大鼠损伤脊髓中,产生了显著的功能恢复,可能与诱导抗炎的M2类巨噬细胞的免疫调节活动有关。 人牙髓干细胞具有分化为许旺细胞的能力,除了这种动态分化能力,还具有旁分泌效应[33]。王爱等[34]采用经典的Rice法建立新生大鼠缺氧缺血性脑损伤模型,通过尼氏染色法观察海马CA1区神经元的变化,利用免疫组化法测定环磷酸腺苷效应元件结合蛋白的表达,结果表明人牙髓干细胞移植可通过促进海马CA1区CREB的表达,改善缺氧缺血性脑损伤新生大鼠远期学习记忆能力,从而修复新生大鼠缺氧缺血性脑损伤。IGF1受体是表达在牙髓干细胞上的一种胚胎干细胞多能性的标志物,代表着自我更新和分化的潜力。牙髓干细胞分泌IGF1与IGF1受体作用并通过自分泌信号通路保持自我更新和增殖潜能。在新生缺氧缺血大鼠中立体定向植入IGF1受体后可以通过增强抗凋亡蛋白Bcl-2的表达,提高神经的可塑性[35]。 2.3.4 血管构建 牙髓是高度血管化和受神经支配的组织,包含有多向分化潜力的一组异质性的干细胞。Gandia等[36]利用大鼠模型研究人牙髓干细胞对于诱导性心肌梗死的治疗效果,他们发现随着时间的延长,梗死部位缩小并伴有新生血管的生成,这可能是由于旁分泌血管内皮生长因子发挥了一定的作用。Iohara等[37]在2008年也从猪牙髓中分离出高度成血管样的细胞。CD31/CD146阴性表达的牙髓干细胞能表达CD34和VEGFR2,且在基质胶上能形成髓样和管样结构,证明其具有新生神经血管的能力。CD105+阳性的牙髓干细胞也证实有同样的特性[38]。牙髓干细胞成血管的特性为治疗血管不足相关疾病寻觅了一条新的途径。收集人牙髓干细胞的条件培养液能获得广泛的生长因子包括脑源性神经营养因子、神经生长因子、血管内皮生长因子和胶质细胞源性神经营养因子。将含有含肽凝胶和牙髓干细胞的三维立体打印的羟基磷灰石支架植入免疫功能低下小鼠,发现有血管生长和牙髓样组织形成,骨形成蛋白沉积表明人牙髓干细胞具有成骨/牙源性分化能力[39]。Silva等[40]评估了脂蛋白受体相关蛋白6(LRP6)和Frizz6对牙髓干细胞内皮分化及由牙髓干细胞介导的毛细血管形成的影响。他们发现,脂蛋白受体相关蛋白6(LRP6)介导的信号通路对于牙髓干细胞的血管分化至关重要。牙髓干细胞形成血管的特性为治疗血管不足相关疾病寻觅了一条新的途径。 2.3.5 角膜重建 Gomes等[41]将一个基于牙髓干细胞制作的组织工程片移植到角膜缺损实验兔模型中,发现能促进实验兔角膜上皮重建。视网膜由神经元、光感受器细胞、双极细胞和视网膜神经节细胞相互连接而成,是一个复杂的三层结构[42]。研究证明,光感受器移植到视网膜外核层能恢复视觉功能[43]。然而,从年轻捐赠者的眼睛获得大量光感受器在临床上并不可行[44-45]。干细胞易获取,能分化成光感受器细胞,因此成为治疗老年性视网膜黄斑变性的最理想来源,具体的机制尚未完全被阐明。最近有报道表明,在损伤的器官模型视网膜中发现牙髓干细胞可以诱导分化为光感受器细胞[46-47]。牙髓干细胞具有良好的自我更新能力与多向分化潜能,这些都是牙髓干细胞构建角膜应用模型的基础和前提。随着研究的进一步深入,炎症牙髓干细胞在角膜重建方面必将有更深和更广阔的发展。 2.3.6 软骨形成 牙髓干细胞的一些种群能表达形成软骨的特性。从牙髓中提取SP细胞,Ⅱ型胶原蛋白和聚糖的表达证实有近30%的SP细胞能转化为软骨细胞[48],其他牙髓干细胞在体外实验中也验证出具有表达成软骨细胞标志物的能力[49-50],培养早期阶段的牙髓干细胞可以分化为成牙本质、骨和软骨的结构,但培养晚期能分化为成骨细胞。Westin等[51]对牙髓干细胞的黏附、增殖及向软骨细胞分化的现象进行研究,进行这项工作的目的是为了拓宽治疗软骨病变组织工程相关的细胞来源。多孔壳聚糖黄原胶(C-X)用作生物支架,kartogenin作为牙髓干细胞选择性向软骨细胞定向分化的促进剂。扫描电镜观察牙髓干细胞在支架上的生物行为,组织学分析法评价牙髓干细胞的分化。结果表明,此方法能获得一个稳定的平均厚度为(0.89±0.01) mm的生物支架及吸收能力很高的培养基(13.20±1.88) g/g,且 kartogenin浓度低至100 nmol/L也可以有效地诱导牙髓干细胞诱导分化为软骨细胞,这一研究现象表明牙髓干细胞的应用可能是组织工程治疗软骨病变的有效措施[51]。 2.4 牙髓干细胞在再生医学的最新进展 牙髓间充质干细胞是来源于牙髓的间充质干细胞。牙髓间充质干细胞增殖能力显著,传代多次后仍会保持其干细胞特性[52]。牙髓间充质干细胞表达STRO-1阳性,且多数表达STRO-1阳性的牙髓间充质干细胞也表达外膜相关抗原。间充质干细胞可以从成年人牙齿、人乳牙、牙周韧带、根尖未成熟恒牙中获取[53-54]。其中,乳牙来源的间充质干细胞凭借比成人牙齿更高的增殖潜力和多向分化潜力具有其独特的优势。最近的研究表明,牙髓间充质干细胞可诱导宿主免疫调节机制,并证实牙髓间充质干细胞应用于临床实践的可能性[55-56]。原位肝移植是临床上患难治性肝脏疾病患者获救的惟一方法[57]。然而,供体短缺、术后严重并发症、成本效益和伦理问题限制其临床应用[58]。Ishkitiev等[59]是第一个发现牙髓来源的间充质细胞可以分化为肝细胞,在肝细胞生长因子、地塞米松和抑瘤素存在的条件下,乳牙牙髓干细胞可以转换成肝细胞的形态,并产生IGF-1和白蛋白。已有报道表明,在特定生长因子的诱导下,无血清培养基中的牙髓干细胞具有分化为肝细胞的潜能,这也显示牙髓干细胞是治疗顽固性肝脏疾病有前景的种子细胞。目前,动物实验模型已经证实了基于牙髓干细胞治疗肝脏疾病的安全性和有效性,在再生医学中运用引导性多功能干细胞也引起了较多的临床关注[60]。 将牙髓干细胞作为临床治疗的细胞来源应用于再生医学引起了越来越多的关注度[60],如心肌性糖尿病、类风湿性关节炎、梗死性糖尿病、帕金森综合征、老年痴呆疾病和难治性肌肉疾病[61-66]。"

| [1] Wang Z, Pan J, Wright JT, et al. Putative stem cells in human dental pulp with irreversible pulpitis: an exploratory study. J Endod. 2010;36(5):820-825. [2] Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I, et al. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8(4):315-317.[3] Huang AH, Chen YK, Chan AW, et al. Isolation and characterization of human dental pulp stem/stromal cells from nonextracted crown-fractured teeth requiring root canal therapy. J Endod. 2009;35(5):673-681.[4] 王亦菁,金岩,史俊南,等.人牙髓干细胞培养及其细胞表型的分析研究[J].临床口腔医学杂志,2005,21(1):23-25.[5] Karaöz E, Demircan PC, Sa?lam O, et al. Human dental pulp stem cells demonstrate better neural and epithelial stem cell properties than bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Histochem Cell Biol. 2011;136(4):455-473.[6] Hakki SS, Kayis SA, Hakki EE, et al. Comparison of mesenchymal stem cells isolated from pulp and periodontal ligament. J Periodontol. 2015;86(2):283-291.[7] Kawashima N. Characterisation of dental pulp stem cells: a new horizon for tissue regeneration. Arch Oral Biol. 2012;57(11): 1439-1458.[8] Nuti N, Corallo C, Chan BM, et al. Multipotent Differentiation of Human Dental Pulp Stem Cells: a Literature Review. Stem Cell Rev. 2016;12(5):511-523.[9] Alge DL, Zhou D, Adams LL, et al. Donor-matched comparison of dental pulp stem cells and bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in a rat model. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2010;4(1):73-81.[10] d'Aquino R, De Rosa A, Laino G, et al. Human dental pulp stem cells: from biology to clinical applications. J Exp Zool B Mol Dev Evol. 2009;312B(5):408-415.[11] Takebe Y, Tatehara S, Fukushima T, et al. Cryopreservation Method for the Effective Collection of Dental Pulp Stem Cells. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2017;23(5):251-261.[12] Yu J, He H, Tang C, et al. Differentiation potential of STRO-1+ dental pulp stem cells changes during cell passaging. BMC Cell Biol. 2010;11:32.[13] Gong T, Heng BC, Lo EC, et al. Current Advance and Future Prospects of Tissue Engineering Approach to Dentin/Pulp Regenerative Therapy. Stem Cells Int. 2016;2016:9204574..[14] Oshima M, Mizuno M, Imamura A, et al. Functional tooth regeneration using a bioengineered tooth unit as a mature organ replacement regenerative therapy. PLoS One. 2011;6(7):e21531. [15] Dadu SS. Tooth regeneration: current status. Indian J Dent Res. 2009;20(4):506-507. [16] Yang KC, Wang CH, Chang HH, et al. Fibrin glue mixed with platelet-rich fibrin as a scaffold seeded with dental bud cells for tooth regeneration. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2012;6(10): 777-785.[17] Liu M, Sun Y, Liu Y, et al. Modulation of the differentiation of dental pulp stem cells by different concentrations of β-glycerophosphate. Molecules. 2012;17(2):1219-1232.[18] 郑丽珠,李小兵,张苗,等. 牙髓干细胞在壳聚糖-纤维蛋白原复合支架材料上的黏附与增殖[J].中国组织工程研究,2017,21(10): 1552-1557.[19] Piva E, Silva AF, Nör JE. Functionalized scaffolds to control dental pulp stem cell fate.J Endod. 2014;40(4 Suppl):S33-40.[20] 王洁,刘加强,房兵.牙髓干细胞在组织工程中的研究进展[J].口腔颌面修复学杂志,2013,14(3):183-186. [21] 史诗彧,谢家敏. 牙髓干细胞在组织工程领域的研究进展[J].华西口腔医学杂志,2015,33(6):656-659.[22] Ding G, Liu Y, Wang W, et al. Allogeneic periodontal ligament stem cell therapy for periodontitis in swine. Stem Cells. 2010; 28(10):1829-1838.[23] Stout BM, Alent BJ, Pedalino P, et al. Enamel matrix derivative: protein components and osteoinductive properties. J Periodontol. 2014;85(2):e9-e17.[24] d'Aquino R, De Rosa A, Lanza V, et al. Human mandible bone defect repair by the grafting of dental pulp stem/progenitor cells and collagen sponge biocomplexes. Eur Cell Mater. 2009;18: 75-83.[25] Giuliani A, Manescu A, Langer M, et al. Three years after transplants in human mandibles, histological and in-line holotomography revealed that stem cells regenerated a compact rather than a spongy bone: biological and clinical implications. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2013;2(4):316-324.[26] Brunelli G, Motroni A, Graziano A, et al. Sinus lift tissue engineering using autologous pulp micro-grafts: A case report of bone density evaluation. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2013;17(5): 644-647.[27] Iaculli F, Di Filippo ES, Piattelli A, et al. Dental pulp stem cells grown on dental implant titanium surfaces: An in vitro evaluation of differentiation and microRNAs expression. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2017;105(5):953-965.[28] Yuan J, Liu X, Chen Y, et al. Effect of SOX2 on osteogenic differentiation of dental pulp stem cells. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand). 2017;63(1):41-44.[29] Xia Y, Chen H, Zhang F, et al. Gold nanoparticles in injectable calcium phosphate cement enhance osteogenic differentiation of human dental pulp stem cells. Nanomedicine. 2018;14(1):35-45.[30] Paduano F, Marrelli M, White LJ, et al. Odontogenic Differentiation of Human Dental Pulp Stem Cells on Hydrogel Scaffolds Derived from Decellularized Bone Extracellular Matrix and Collagen Type I. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0148225.[31] Mortada I, Mortada R, Al Bazzal M. Dental Pulp Stem Cells and Neurogenesis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017 Jul 8. doi: 10.1007/5584_2017_71. [Epub ahead of print][32] Matsubara K, Matsushita Y, Sakai K, et al. Secreted ectodomain of sialic acid-binding Ig-like lectin-9 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 promote recovery after rat spinal cord injury by altering macrophage polarity. J Neurosci. 2015;35(6): 2452-2464.[33] Askari N, Yaghoobi MM, Shamsara M, et al. Human Dental Pulp Stem Cells Differentiate into Oligodendrocyte Progenitors Using the Expression of Olig2 Transcription Factor. Cells Tissues Organs. 2014;200(2):93-103.[34] 王爱,牟青杰,王晓莉,等. 牙髓干细胞移植治疗缺氧缺血性脑损伤新生大鼠远期行为学及环磷酸腺苷反应元件结合蛋白的变化[J].中国组织工程研究,2017,21(5):701-706.[35] Chiu HY, Lin CH, Hsu CY, et al. IGF1R+ Dental Pulp Stem Cells Enhanced Neuroplasticity in Hypoxia-Ischemia Model. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54(10):8225-8241.[36] Gandia C, Armiñan A, García-Verdugo JM, et al. Human dental pulp stem cells improve left ventricular function, induce angiogenesis, and reduce infarct size in rats with acute myocardial infarction. Stem Cells. 2008;26(3):638-645.[37] Iohara K, Zheng L, Wake H, et al. A novel stem cell source for vasculogenesis in ischemia: subfraction of side population cells from dental pulp. Stem Cells. 2008;26(9):2408-2418.[38] Nakashima M, Iohara K, Sugiyama M. Human dental pulp stem cells with highly angiogenic and neurogenic potential for possible use in pulp regeneration. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2009;20(5-6):435-440.[39] Lambrichts I, Driesen RB, Dillen Y, et al. Dental Pulp Stem Cells: Their Potential in Reinnervation and Angiogenesis by Using Scaffolds. J Endod. 2017;43(9S):S12-S16.[40] Silva GO, Zhang Z, Cucco C, et al. Lipoprotein Receptor-related Protein 6 Signaling is Necessary for Vasculogenic Differentiation of Human Dental Pulp Stem Cells. J Endod. 2017;43(9S): S25-S30.[41] Gomes JA, Geraldes Monteiro B, Melo GB, et al. Corneal reconstruction with tissue-engineered cell sheets composed of human immature dental pulp stem cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(3):1408-1414.[42] Berry M, Ahmed Z, Lorber B, et al. Regeneration of axons in the visual system. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2008;26(2-3):147-174.[43] Yamagata M, Yamamoto A, Kako E, et al. Human dental pulp-derived stem cells protect against hypoxic-ischemic brain injury in neonatal mice. Stroke. 2013;44(2):551-554.[44] Lamba DA, McUsic A, Hirata RK, et al. Generation, purification and transplantation of photoreceptors derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells. PLoS One. 2010;5(1):e8763.[45] MacLaren RE, Pearson RA, MacNeil A, et al. Retinal repair by transplantation of photoreceptor precursors. Nature. 2006; 444(7116):203-237.[46] Mead B, Logan A, Berry M, et al. Concise Review: Dental Pulp Stem Cells: A Novel Cell Therapy for Retinal and Central Nervous System Repair. Stem Cells. 2017;35(1):61-67.[47] Bray AF, Cevallos RR, Gazarian K, et al. Human dental pulp stem cells respond to cues from the rat retina and differentiate to express the retinal neuronal marker rhodopsin. Neuroscience. 2014;280:142-155.[48] Iohara K, Zheng L, Ito M, et al. Side population cells isolated from porcine dental pulp tissue with self-renewal and multipotency for dentinogenesis, chondrogenesis, adipogenesis, and neurogenesis. Stem Cells. 2006;24(11):2493-2503.[49] Sonoyama W, Liu Y, Yamaza T, et al. Characterization of the apical papilla and its residing stem cells from human immature permanent teeth: a pilot study. J Endod. 2008;34(2):166-171.[50] Huang AH, Chen YK, Chan AW, et al. Isolation and characterization of human dental pulp stem/stromal cells from nonextracted crown-fractured teeth requiring root canal therapy. J Endod. 2009;35(5):673-681.[51] Westin CB, Trinca RB, Zuliani C, et al. Differentiation of dental pulp stem cells into chondrocytes upon culture on porous chitosan-xanthan scaffolds in the presence of kartogenin. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2017;80:594-602.[52] Liu H, Gronthos S, Shi S. Dental pulp stem cells. Methods Enzymol. 2006;419:99-113.[53] Sonoyama W, Liu Y, Yamaza T, et al. Characterization of the apical papilla and its residing stem cells from human immature permanent teeth: a pilot study. J Endod. 2008;34(2):166-171.[54] Marrelli M, Paduano F, Tatullo M. Cells isolated from human periapical cysts express mesenchymal stem cell-like properties. Int J Biol Sci. 2013;9(10):1070-1078.[55] Demircan PC, Sariboyaci AE, Unal ZS, et al. Immunoregulatory effects of human dental pulp-derived stem cells on T cells: comparison of transwell co-culture and mixed lymphocyte reaction systems. Cytotherapy. 2011;13(10):1205-1220.[56] Gronthos S. The therapeutic potential of dental pulp cells: more than pulp fiction. Cytotherapy. 2011;13(10):1162-1163.[57] Ohkoshi S, Hara H, Hirono H, et al. Regenerative medicine using dental pulp stem cells for liver diseases. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther. 2017;8(1):1-6.[58] Zarrinpar A, Busuttil RW. Liver transplantation: past, present and future. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10(7):434-440.[59] Ishkitiev N, Yaegaki K, Calenic B, et al. Deciduous and permanent dental pulp mesenchymal cells acquire hepatic morphologic and functional features in vitro. J Endod. 2010; 36(3):469-474.[60] Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. A decade of transcription factor-mediated reprogramming to pluripotency. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016;17(3):183-193.[61] Kanafi MM, Rajeshwari YB, Gupta S, et al. Transplantation of islet-like cell clusters derived from human dental pulp stem cells restores normoglycemia in diabetic mice. Cytotherapy. 2013; 15(10):1228-1236.[62] Fujii H, Matsubara K, Sakai K, et al. Dopaminergic differentiation of stem cells from human deciduous teeth and their therapeutic benefits for Parkinsonian rats. Brain Res. 2015;1613:59-72.[63] Mita T, Furukawa-Hibi Y, Takeuchi H, et al. Conditioned medium from the stem cells of human dental pulp improves cognitive function in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Behav Brain Res. 2015;293:189-197.[64] Gandia C, Armiñan A, García-Verdugo JM, et al. Human dental pulp stem cells improve left ventricular function, induce angiogenesis, and reduce infarct size in rats with acute myocardial infarction. Stem Cells. 2008;26(3):638-645.[65] Ishikawa J, Takahashi N, Matsumoto T, et al. Factors secreted from dental pulp stem cells show multifaceted benefits for treating experimental rheumatoid arthritis. Bone. 2016;83:210-219. [66] Kerkis I, Ambrosio CE, Kerkis A, et al. Early transplantation of human immature dental pulp stem cells from baby teeth to golden retriever muscular dystrophy (GRMD) dogs: Local or systemic. J Transl Med. 2008;6:35. |

| [1] | Pu Rui, Chen Ziyang, Yuan Lingyan. Characteristics and effects of exosomes from different cell sources in cardioprotection [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(在线): 1-. |

| [2] | Lin Qingfan, Xie Yixin, Chen Wanqing, Ye Zhenzhong, Chen Youfang. Human placenta-derived mesenchymal stem cell conditioned medium can upregulate BeWo cell viability and zonula occludens expression under hypoxia [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(在线): 4970-4975. |

| [3] | Zhang Tongtong, Wang Zhonghua, Wen Jie, Song Yuxin, Liu Lin. Application of three-dimensional printing model in surgical resection and reconstruction of cervical tumor [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(9): 1335-1339. |

| [4] | Zhang Xiumei, Zhai Yunkai, Zhao Jie, Zhao Meng. Research hotspots of organoid models in recent 10 years: a search in domestic and foreign databases [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(8): 1249-1255. |

| [5] | Hou Jingying, Yu Menglei, Guo Tianzhu, Long Huibao, Wu Hao. Hypoxia preconditioning promotes bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells survival and vascularization through the activation of HIF-1α/MALAT1/VEGFA pathway [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 985-990. |

| [6] | Shi Yangyang, Qin Yingfei, Wu Fuling, He Xiao, Zhang Xuejing. Pretreatment of placental mesenchymal stem cells to prevent bronchiolitis in mice [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 991-995. |

| [7] | Liang Xueqi, Guo Lijiao, Chen Hejie, Wu Jie, Sun Yaqi, Xing Zhikun, Zou Hailiang, Chen Xueling, Wu Xiangwei. Alveolar echinococcosis protoscolices inhibits the differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells into fibroblasts [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 996-1001. |

| [8] | Fan Quanbao, Luo Huina, Wang Bingyun, Chen Shengfeng, Cui Lianxu, Jiang Wenkang, Zhao Mingming, Wang Jingjing, Luo Dongzhang, Chen Zhisheng, Bai Yinshan, Liu Canying, Zhang Hui. Biological characteristics of canine adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells cultured in hypoxia [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 1002-1007. |

| [9] | Geng Yao, Yin Zhiliang, Li Xingping, Xiao Dongqin, Hou Weiguang. Role of hsa-miRNA-223-3p in regulating osteogenic differentiation of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 1008-1013. |

| [10] | Lun Zhigang, Jin Jing, Wang Tianyan, Li Aimin. Effect of peroxiredoxin 6 on proliferation and differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells into neural lineage in vitro [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 1014-1018. |

| [11] | Zhu Xuefen, Huang Cheng, Ding Jian, Dai Yongping, Liu Yuanbing, Le Lixiang, Wang Liangliang, Yang Jiandong. Mechanism of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells differentiation into functional neurons induced by glial cell line derived neurotrophic factor [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 1019-1025. |

| [12] | Duan Liyun, Cao Xiaocang. Human placenta mesenchymal stem cells-derived extracellular vesicles regulate collagen deposition in intestinal mucosa of mice with colitis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 1026-1031. |

| [13] | Pei Lili, Sun Guicai, Wang Di. Salvianolic acid B inhibits oxidative damage of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and promotes differentiation into cardiomyocytes [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 1032-1036. |

| [14] | Guan Qian, Luan Zuo, Ye Dou, Yang Yinxiang, Wang Zhaoyan, Wang Qian, Yao Ruiqin. Morphological changes in human oligodendrocyte progenitor cells during passage [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 1045-1049. |

| [15] | Wang Zhengdong, Huang Na, Chen Jingxian, Zheng Zuobing, Hu Xinyu, Li Mei, Su Xiao, Su Xuesen, Yan Nan. Inhibitory effects of sodium butyrate on microglial activation and expression of inflammatory factors induced by fluorosis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 1075-1080. |

| Viewed | ||||||

|

Full text |

|

|||||

|

Abstract |

|

|||||