Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research ›› 2019, Vol. 23 ›› Issue (36): 5875-5881.doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-4344.1977

Previous Articles Next Articles

Treatment strategies for spinal metastases: advantages of 3D printing and precise treatment

Cui Jiaming, Yang Dazhi

- Second Clinical Medical College of Jinan University, Shenzhen 518000, Guangdong Province, China

-

Online:2019-12-28Published:2019-12-28 -

About author:Cui Jiaming, Master candidate, Second Clinical Medical College of Jinan University, Shenzhen 518000, Guangdong Province, China

CLC Number:

Cite this article

Cui Jiaming, Yang Dazhi. Treatment strategies for spinal metastases: advantages of 3D printing and precise treatment[J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2019, 23(36): 5875-5881.

share this article

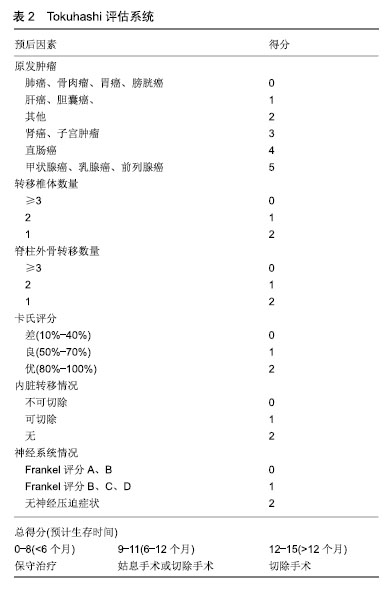

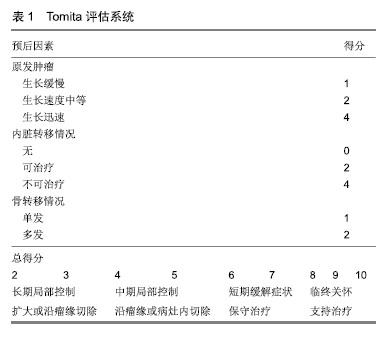

2.1 诊断 对有肿瘤史的患者出现后背痛以及相应神经症状时,需要高度警惕肿瘤转移脊柱的可能。目前脊柱转移瘤的诊断主要依靠影像学表现。X射线通常作为基础检查,但不能作早期诊断,一般认为正常骨组织出现50%的异常才能在X射线当中做出明确诊断[3]。CT的密度分辨率要高出X射线10倍,可以清晰地看到骨小梁结构,且没有重影。在椎体塌陷、骨质疏松和类肿瘤显像上,CT具有较高的灵敏度和特异度。相比X射线而言,CT可以看见更小的溶骨灶,坏死骨、钙化灶、虱咬状骨破坏以及椎旁病灶也能较好的成像[4]。溶骨性病灶常发生在椎体的皮质、前外侧及后侧,这一点有助于诊断转移瘤来源。其典型表现往往是皮质骨骨折、椎体内骨折、地图样改变以及真空影。成骨性病灶较少见,其成像特点是密度增高(但仍低于皮质骨密度),混杂密度影,边界模糊不清以及骨膜反应。MRI检查对脊柱转移里的诊断主要依据骨髓的改变。肿瘤病灶在T1和T2加权成像上均成明显低信号。但由于肿瘤和脂肪成同等信号,所以压脂像比T1、T2加权成像更加敏感。同时MRI可以详细地看到脊髓得压迫,骨质、神经及椎旁组织的侵犯。单光子发射计算机断层成像通过放射性核素99Tcm衰变产生140 keV的低能γ光子,根据组织的代谢程度而表现不同的浓聚,从而可早期诊断不同肿瘤的骨转移[5]。18氟-氟代脱氧葡萄糖正电子发射计算机断层成像/CT显像(18F-FDG PET)可全身扫描,常发现脊柱外病灶。其原理是利用肿瘤转移早期葡萄糖代谢升高的原理,对诊断溶骨性转移灶的灵敏度高,诊断成骨性转移灶的灵敏度低,因为成骨病灶的侵袭性相对较低、糖代谢率亦较低[6]。 2.2 病情评估 目前对脊柱转移瘤患者治疗方案的选择主要依赖于对患者预后的评估,过于保守的治疗不能使脊髓充分减压、椎体形态重塑以及脊柱重构良好的稳定性。而过于激进的手术使患者因此承担了不必要的治疗风险,从而缩短了本该有的生存时间。 有关脊柱转移瘤患者的病情评估的研究已有30余年历史,根据临床指导内容主要分为2大类,一类是预测患者生存时间的评估系统,如Sioutos评分[7]、van der Linden评分[8]、Rades评分[9]、Bollen评分等[10]。一类是临床决策指导规则,如Tomita评分[11]、Tokuhashi评分[12]、Leithner评分等[13]。目前在临床工作中常用的几种脊柱转移瘤病情评估系统归纳如下。 2001年Tomita等[14]将3个主要的影响预后因素(原发肿瘤的生长速度,内脏转移有无及可治疗性,单发或多发骨转移)作为基准提出了Tomita评估系统。评分为2-3分者建议扩大切除或沿病灶边缘切除;4-5分者建议沿灶缘切除或灶内切除;6-7分者建议姑息手术治疗;8-10分者建议支持治疗。2005年Tokuhashi等[15]在其1989年提出的评分系统进一步改进,提出6项影响预后因子作为评估参数:原发肿瘤类型、受累椎体数量、受累除脊柱外的骨骼数量、卡氏评分、受累内脏器官、麻痹症状。其评分为0-8分者,预计生存时间小于6个月,建议保守治疗或姑息手术治疗;评分为9-11分者,预计生存时间6-12个月,建议姑息手术,或椎体切除术(限单一椎体受累且无内脏器官转移患者);评分为12-15分者,预计生存时间超过12个月,建议椎体切除术。2011年Paton等提出了LMNOP评估系统,其字母代表含义如下:L:肿瘤位置及数量;M:脊柱的稳定性;N:神经功能;O:肿瘤学特征;P:患者的全身情况。LMNOP系统建议对于出现脊柱不稳或者出现神经系统损害的患者,当其自身情况可耐受时可行手术治疗。若不伴有神经系统受压或轻度脊柱不稳时可行椎体成形术。2013年Laufer等[16]将神经病学、肿瘤学、生物力学、全身系统情况4部分作为评估内容,提出了NOMS决策框架。NOMS决策框架结合了现阶段脊柱转移瘤诊疗新技术与循证医学证据,综合上述4项评估内容,多学科协作共同制定最佳治疗方案。 目前已有大量研究从外部证实这些脊柱转移瘤病情评估系统的可靠性,但是尚没有研究证实某一种评估模型优于另一种[17-19]。Collins等[20]的一篇系统回顾中提到,大部分试图验证评估系统的研究质量偏低,其原因可能是研究设计的缺陷,缺乏充足的数据,处理缺失数据不合理以及不能自身校正的问题。 Bollen等[21]的一项回顾性队列研究中,分析了1 379例脊柱转移瘤患者的临床数据,发现脊柱转移瘤患者的预期寿命主要取决于原发肿瘤的组织学特点,并以Karnofsky评分作为脊柱转移瘤患者手术治疗后生活质量的强预测因子。此项研究还比较了Tomita,Tokuhashi,Van der Linden,Bauer,Rades和Bollen六种评估系统,见表1,2。结果发现Bollen评估系统准确性优于其他5种评估系统(曲线下面积0.7),意味着这一队列的患者分为死亡和生存2组,随机挑选出1例患者,Bollen评估系统能准确判断此患者来自哪一个组的概率为70%。Choi等[22]的一篇前瞻性队列研究中,纳入了922例接受手术治疗的脊柱转移瘤患者,通过对患者手术前后情况的评估,发现原发肿瘤的类型,椎体转移的数量和内脏转移与否是最有用的生存预测因素。而术前Karnofsky评分,Frankel评分和EQ-5D评分可以很好地评估脊柱转移瘤患者的生活质量。并且无论脊柱转移瘤患者术前神经功能状态如何,术前Karnofsky评分低于60分的患者将无法从手术中获益。Verlaan等[23]的一项大型队列研究中,分析比较了脊柱转移瘤手术后生存不到3个月和生存2年以上的患者的特征,发现大多数术后3个月内死亡的患者是由于原发肿瘤病情的急剧恶化造成的,并非是由于手术并发症引起的,这表明脊柱转移瘤患者术后的生存时间是由手术因素和患者全身情况共同决定的。Nater等[24]通过调查问卷全球438例AO Spine成员,发现大多数受访成员认为年龄因素不会对脊柱转移瘤患者的生存时间产生负面影响,并认为内脏转移情况和原发肿瘤的部位是影响脊柱转移瘤患者预后的重要因素,而术前患者的Frankel评分、括约肌功能、独立行走能力以及Karnofsky评分是脊柱转移瘤患者生活质量的重要评估因素。 "

2.3 治疗 2.3.1 放射治疗 放射治疗常作为手术后辅助治疗的手段。体外放射治疗可以暂时缓解脊柱转移瘤患者的疼痛,但无法对肿瘤进行长期有效的控制,立体定向放疗便实现了这一需求[25]。Chang等[26]的一项立体定向放疗治疗脊柱寡转移瘤的多中心研究中,入组了60例脊柱转移瘤患者,平均随访2年,局部肿瘤无进展率为76%。Ito等[27]回顾性地分析了131例接受立体定向放疗的脊柱转移瘤患者,1年后随访发现肿瘤的局部控制率为72.3%,患者的长期疼痛控制率为61.7%。即便是对放疗不敏感的肾癌、肉瘤和黑色素瘤,立体定向放疗也能够有效的控制肿瘤的局部进展,降低脊髓压迫以及脊柱不稳的出现[28]。但目前有关立体定向放疗治疗脊柱转移瘤的数据仅限于单个或小型多中心回顾性研究和一些前瞻性试验,鉴于证据质量的局限性以及患者和肿瘤特征的异质性,尚不能得出立体定向放疗在治疗上优于体外放射治疗的结论。因此立体定向放疗治疗脊柱转移瘤的优越性仍需大量高级别的证据进一步证实。 2.3.2 脊柱微创手术 脊柱微创手术目前尚没有明确的定义,但大多数学者认为脊柱微创手术是通过尽可能少的切开及牵拉椎旁肌肉,从自然解剖层面入路,保留脊柱后运动节段和椎旁肌肉,从而减少术中出血以及术后患者疼痛,加速患者术后恢复时间,提高治疗效果[29-31]。 Lau等[32]报道了49例脊柱转移瘤患者,其中21例患者接受了脊柱微创手术(经椎弓根椎体切除术,后路减压术和经筋膜内固定术),28例患者接受了开放性手术。研究显示脊柱微创手术组的患者平均术中出血量、围术期并发症发病率及住院时间明显少于开放手术组。 Miscusi等[33]回顾性地分析了23例接受脊柱微创手术的脊柱转移瘤患者,其平均术中出血量为240 mL,平均手术时间为2.2 h,术后平均卧床时间为2 d,术后74%的患者目测类比疼痛评分较术前明显改善。 Hansen-Algenstaedt等[34]对60例接受手术治疗的脊柱转移瘤患者进行了一项病例对照研究,其中30例接受开放性后路减压椎体融合术,30例接受经皮椎弓根螺钉固定术。研究显示,接受脊柱微创手术组的患者需要内固定的节段较多,术中透视时间更长,但脊柱微创手术组的患者需要后路减压的患者较少,术中出血量及住院时间均较开放手术组的患者少。2组手术后的治疗效果大致相似。在接受脊柱微创手术组中,20%的患者提高了至少1个以上的Frankel等级;术后第7天平均目测类比疼痛评分为2.0分;在术后3个月随访时平均目测类比疼痛评分为5.2分,Karnofsky评分的改善率为10%。在接受开放手术组中,33.3%的患者提高了至少1个以上的Frankel等级;术后第7天平均疼痛目测类比评分为3.1分;在3个月随访时平均疼痛目测类比评分为4.6分,Karnofsky评分改善率为20%。 2.3.3 椎体成形术 对于一般全身情况较差不能耐受开放手术或多发转移灶的患者,可考虑行经皮椎体成形术,经皮椎体成形术后患者的疼痛缓解率为73%-100%[35]。一项分析性研究观察了32例因脊柱转移瘤导致椎体压缩性骨折的患者,发现患者在经皮椎体成形术后第1天疼痛明显得到缓解,并且此效果可持续1年[36]。由于椎体成形术软组织创伤小,失血少以及可在局麻下完成手术,椎体成形手术相比于开放性手术具有较少的并发症以及较低的死亡风险。 当不考虑手术技术以及放射设备时,骨水泥的黏度已被证明是渗漏的关键影响因素[37]。已有大量文献证实高黏度水泥可有效降低渗漏的风险,并且与低黏度骨水泥的治疗效果无明显差异[38-40]。但这些数据大部分来自骨质疏松导致的椎体压缩性骨折的患者,而目前有关高黏度骨水泥治疗脊柱转移瘤患者的文献报道较为罕见。近期Yahyavi-Firouz-Abadi等[41]发表了一篇应用高黏度骨水泥在CT引导下治疗C2,C3椎体转移瘤的病例个案报道,术后患者的疼痛明显缓解,颈椎的活动度得到了改善,且没有术后并发症的发生。他们认为此种手术方式是不能耐受开放手术的脊柱转移瘤患者较为合适的治疗方法。有关高黏度骨水泥治疗脊柱转移瘤的具体疗效以及治疗风险仍需要后续大量的工作进一步证实。 Vessel-X经皮椎体强化系统,又称血管成形术,是一种新型的骨材料填充系统。其设计原理与经皮椎体后凸成形术相似,在建立通道后将骨水泥注入植入的网袋,复位椎体后不需取出。其网袋是由聚对苯二甲酸醇酯材料交错编织制成,可对骨水泥弥散起到缓冲作用,控制骨水泥的流向,灌注压力逐层释放,提高了手术安全性。Klinger等[42]随访了因脊柱转移瘤造成椎体病理性骨折的11例患者,均接受血管成形术治疗,其中9例伴有严重的椎体后壁缺损。术后3个月随访时,所有患者的目测类比评分、Oswestry功能障碍指数及SF-36评分均有明显改善,并且没有观察到骨水泥渗漏及其他手术并发症。该作者认为,即使在椎体后壁缺损的情况下,血管成形术也可以是病理性椎体骨折的治疗选择之一。唐海等[43]回顾性分析了32例使用血管成形术治疗的脊柱转移瘤患者,平均随访时间6个月。在末次随访时,患者的目测类比评分明显降低(P < 0.05)。共3例患者发生少量骨水泥渗漏,骨水泥渗漏率7.9%,且均无临床症状。 2.3.4 开放手术 开放手术治疗的一个基本条件是患者全身情况足以耐受手术。大多数作者认为,预期寿命应该超过3个月是开放手术的适应证[44]。传统开放手术治疗包括后路椎板切除减压、椎体部分切除、椎体分块或整块切除并实施椎弓根钉固定,维持脊柱稳定性。目前开放手术仍是快速进展的脊柱转移瘤脊髓压迫症患者以及病理骨折风险高的溶骨性脊柱转移瘤患者的首选治疗方式。手术作为一种姑息治疗手段,术中尽可能的去除肿瘤组织并矫正脊柱畸形,从而缓解临床症状[45]。 单纯的椎板切除手术不常规使用,因为它存在造成脊柱不稳的风险。然而当肿瘤只侵犯椎体后柱或是位于硬膜外时,单纯椎板切除术可作为手术方式的选择[46]。值得注意的是,这些患者日后会因放疗而造成脊柱畸形,从而需要进一步采取脊柱内固定手术的治疗[47]。 椎体整块切除术可以广泛切除瘤灶、假包膜、反应区以及周围部分正常组织。Tomita [48]在椎体整块切除术的基础上进一步改进,发明了全椎体切除术,它适用于原发肿瘤未侵犯周围内脏器官、不与大血管发生粘连以及非多发转移的患者。此手术方式包括前后方椎体的整块切除术以及后方内固定系统,相继有大量文献相继报道,就肿瘤复发率及肿瘤相关并发症而言,全椎体切除术具有明显优势[49-51]。 2.3.5 放疗联合手术 手术治疗可使椎管减压以及加强脊柱的稳定性,但是肿瘤的长期控制有赖于有效的放疗、化疗和靶向治疗等。对放疗敏感的肿瘤在术后常规放疗的2年控制率可达80%,而对放疗不敏感的肿瘤在术后常规放疗的2年控制率仅为50%[52]。立体定向放疗使用了多条光束来传递高剂量的辐射,同时不损伤邻近的正常组织,尤其是脊髓。立体定向放疗高效的肿瘤控制率使得过去10年里肿瘤切除手术逐渐减少,脊柱转移瘤的手术治疗因此进入了“分离”手术的时代[44]。分离手术是指环脊髓外周减压使得脊髓与肿瘤之间至少有1.0-2.0 mm的空间,从而使立体定向放疗的剂量得以优化[53]。分离手术通常用于Bilsky分级2级以上,发生病理性骨折以及脊柱不稳的患者[54]。Laufer等[47]回顾性地研究了186例接受分离手术并术后放疗的脊柱转移瘤患者,研究显示术后放疗剂量是控制肿瘤进展的唯一相关因素,术后接受高剂量放疗的患者术后1年的局部肿瘤进展率低于5%。Al-Omair等[55]回顾性研究了80例经分离手术后接受立体定向放疗治疗的脊柱转移瘤患者,研究认为在患者接受立体定向放疗前,通过分离手术可使局部肿瘤得到较好控制。并发现Bilsky分级在2级以上的患者经此治疗后的局部肿瘤控制效果显著。 Lu等[56]回顾性分析169例脊柱转移瘤患者,随机分为4组,分别接受4种不同治疗方式:A组49例,接受椎体成形术联合放射性125Ⅰ粒子植入;B组51例,接受椎体成形术联合射频消融治疗;C组38例,接受椎体成形术联合唑来膦酸治疗;D组31例,接受椎体成形术联合放疗。研究结果发现,椎体成形术联合放疗组在缓解患者疼痛方面疗效最佳,其WHO疼痛缓解率最高(P < 0.05)。椎体成形术联合放射性125Ⅰ粒子植入组患者术后的目测类比评分最低,但在改善患者神经功能方面没有体现出足够优势。 尽管手术联合放疗治疗脊柱转移瘤已证实具有较好的疗效,但有关先化疗再手术还是手术后再化疗仍存有争议。已有大量临床随访报道脊柱转移瘤手术后接受放疗可获得较好的肿瘤局部控制和生存结局[25,57-58]。但有关手术前接受放疗的临床报道较少。Steverink等[59]研究了在椎体内固定手术前使用立体定向放疗治疗的10例脊柱转移瘤患者,取得立体定向放疗术前以及术后6 h和21 h后的肿瘤病灶活检进行免疫组织化学染色,发现在立体定向放疗术后21 h的样本中有83%观察到肿瘤细胞坏死,与立体定向放疗术前和术后6 h的样本相比,立体定向放疗术后21 h样本的肿瘤细胞凋亡显着增加。并发现在立体定向放疗术后,病灶活检中的CD31+的血管数量减少,有丝分裂活性也下降。有关脊柱转移瘤术前接受放疗是否能改善患者预后仍需要大量的临床工作进一步证实。 2.3.6 3D打印技术与脊柱转移瘤 3D打印技术是以数字模型文件为基础,运用可黏合材料,通过逐层打印的方式来构造物体的技术,其起源于20世纪80年代并迅速发展,最初主要应用于工业、航天、建筑、汽车等领域。近些年来,随着计算机技术和影像学技术的发展,3D打印技术在医学领域中的应用越来越广泛。 在脊柱转移瘤手术中,如何精准切除肿瘤以及切除肿瘤后如何重建脊柱的稳定性是手术成功的关键。但由于脊柱解剖结构复杂,周围毗邻脊髓、神经等重要组织,加之脊柱转移瘤个体差异较大,CT及MRI等二维影像常常难以反映出脊柱病变的实际情况,增加了术中不可控因素的风险。3D打印一方面可以通过术前模拟肿瘤解剖模型及椎弓根置钉的钉道导板,辅助术中精准切除肿瘤并可以复合自体骨或异体骨重建脊柱的稳定。另一方面可以重建3D椎体,在病椎整块切除后,置入重建的椎体假体,为脊柱转移瘤切除后大段骨缺失提供了一种新的治疗方案。 王琪等[60]利用3D打印对22例脊柱转移瘤患者的病椎进行三维模型重建,并依此制定手术方案,模拟手术操作及预处理内固定物。研究发现3D打印技术可以直观、全面的显示病灶区域的解剖关系,术者可术前对病灶有直观的了解,术中可以更精确、完整的切除肿瘤,避免重要血管、神经的损伤,预处理内植物材料,从而缩短手术时间,减少术中出血。 Girolami等[61]前瞻性观察了13例脊柱转移瘤的患者,在行椎体整块切除肿瘤后植入3D打印椎体进行前柱的重建。平均随访10个月,研究发现,所有患者均发生了相邻椎体下沉,然而其中11例患者(92%)无临床症状,1例患者因椎体下沉程度严重而行二次手术,1例患者因局部肿瘤复发而移除了置入的3D假体,1例患者由于假体和椎体的交界处发生了进行性的后凸而行翻修手术。 由于3D打印技术是新近的脊柱转移瘤的治疗方式,目前缺乏大宗病例报道,且长期随访的治疗效果仍有待考证。但随着工程设计、计算机科学与临床工作的不断合作,生物力学实验和机械与生物重建实验不断探索,3D打印技术呈现出脊柱转移瘤新兴的治疗趋势。 "

| [1]Pennington Z, Ahmed AK, Molina CA, et al. Minimally invasive versus conventional spine surgery for vertebral metastases: a systematic review of the evidence. Ann Transl Med.2018;6(6):103.[2]Nater A, Sahgal A, Fehlings M. Management - spinal metastases. Handb Clin Neurol. 2018;149:239-255.[3]Molina CA, Gokaslan ZL, Sciubba DM. Diagnosis and management of metastatic cervical spine tumors. Orthop Clin North Am. 2012;43(1): 75-87, viii-ix.[4]张丽君. CT与MRI对脊柱转移瘤的诊断价值比较[J].临床医学, 2016, 5(36):91-92.[5]廖骁勇. 脊柱转移瘤的影像学诊断进展[J].颈腰痛杂志, 2016,1(37):61-64.[6]汪建强. 18F-FDG SPECT/CT符合线路显像?99Tcm-MDP骨显像及MRI对脊柱转移瘤诊断效能的对比[J].中华核医学与分子影像杂志,2015, 5(35):403-404.[7]Sioutos PJ, Arbit E, Meshulam CF, et al. Spinal metastases from solid tumors. Analysis of factors affecting survival.Cancer. 1995;76(8): 1453-9145.[8]van der Linden YM, Dijkstra SP, Vonk EJ, et al. Prediction of survival in patients with metastases in the spinal column: results based on a randomized trial of radiotherapy. Cancer. 2005;103(2):320-328.[9]Rades D, Dunst J, Schild SE. The first score predicting overall survival in patients with metastatic spinal cord compression.Cancer. 2008; 112(1):157-161.[10]Bollen L, van der Linden YM, Pondaag W, et al. Prognostic factors associated with survival in patients with symptomatic spinal bone metastases: a retrospective cohort study of 1 043 patients. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16(7):991-998.[11]Tomita K, Kawahara N, Kobayashi T, et al. Surgical strategy for spinal metastases. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26(3):298-306.[12]Tokuhashi Y, Matsuzaki H, Oda H, et al. A revised scoring system for preoperative evaluation of metastatic spine tumor prognosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30(19):2186-2191.[13]Leithner A, Radl R, Gruber G, et al. Predictive value of seven preoperative prognostic scoring systems for spinal metastases.Eur Spine J. 2008;17(11):1488-1495.[14]Tomita K, Kawahara N, Kobayashi T, et al. Surgical strategy for spinal metastases.Spine (Phila Pa 1976).2001;26(3):298-306.[15]Tokuhashi Y, Matsuzaki H, Oda H, et al. A revised scoring system for preoperative evaluation of metastatic spine tumor prognosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976).2005;30(19):2186-2191.[16]Laufer I, Rubin DG, Lis E, et al. The NOMS framework: approach to the treatment of spinal metastatic tumors. Oncologist. 2013;18(6):744-751.[17]Bartels RH, de Ruiter G, Feuth T, et al. Prediction of life expectancy in patients with spinal epidural metastasis.Neuro Oncol. 2016,18(1): 114-118.[18]Goodwin CR, Schoenfeld AJ, Abu-Bonsrah NA, et al. Reliability of a spinal metastasis prognostic score to model 1-year survival. Spine J. 2016;16(9):1102-1108.[19]Whitehouse S, Stephenson J, Sinclair V, et al. A validation of the Oswestry Spinal Risk Index. Eur Spine J. 2016;25(1):247-251.[20]Collins GS, de Groot JA, Dutton S, et al. External validation of multivariable prediction models: a systematic review of methodological conduct and reporting. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:40.[21]Bollen L, Wibmer C, Van der Linden YM, et al. Predictive Value of Six Prognostic Scoring Systems for Spinal Bone Metastases: An Analysis Based on 1379 Patients.Spine (Phila Pa 1976).2016;41(3):E155-162.[22]Choi D, Fox Z, Albert T, et al. Prediction of quality of life and survival after surgery for symptomatic spinal metastases: a multicenter cohort study to determine suitability for surgical treatment. Neurosurgery. 2015;77(5):698-708; discussion [23]Verlaan JJ, Choi D, Versteeg A, et al. Characteristics of patients who survived < 3 months or > 2 years after surgery for spinal metastases: can we avoid inappropriate patient selection? J Clin Oncol. 2016; 34(25):3054-3061.[24]Nater A, Tetreault LL, Davis AM, et al. Key preoperative clinical factors predicting outcome in surgically treated patients with metastatic epidural spinal cord compression: results from a survey of 438 aospine international members. World Neurosurg. 2016;93:436-448.e15.[25]Jabbari S, Gerszten PC, Ruschin M, et al. Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy for Spinal Metastases: Practice Guidelines, Outcomes, and Risks.Cancer J.2016;22(4):280-289.[26]Chang JH, Gandhidasan S, Finnigan R, et al. Stereotactic ablative body radiotherapy for the treatment of spinal oligometastases. Clin Oncol.2017;29(7):e119-e125.[27]Ito K, Ogawa H, Shimizuguchi T, et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for spinal metastases: clinical experience in 134 cases from a single japanese institution.Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2018;17: 1533033818806472. [28]De Bari B, Alongi F, Mortellaro G, et al. Spinal metastases: Is stereotactic body radiation therapy supported by evidences? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol.2016;98:147-158.[29]McAfee PC, Garfin SR, Rodgers WB, et al. An attempt at clinically defining and assessing minimally invasive surgery compared with traditional "open" spinal surgery. SAS J. 2011;5(4):125-130.[30]Smith ZA, Fessler RG. Paradigm changes in spine surgery: evolution of minimally invasive techniques.Nature Rev Neurol. 2012;8(8):443-450.[31]Banczerowski P, Czigleczki G, Papp Z, et al. Minimally invasive spine surgery: systematic review.Neurosurg Rev.2015;38(1):11-26; discussion[32]Lau D, Chou D. Posterior thoracic corpectomy with cage reconstruction for metastatic spinal tumors: comparing the mini-open approach to the open approach. J Neurosurg Spine.2015;23(2):217-227.[33]Miscusi M, Polli FM, Forcato S, et al. Comparison of minimally invasive surgery with standard open surgery for vertebral thoracic metastases causing acute myelopathy in patients with short- or mid-term life expectancy: surgical technique and early clinical results.J Neurosurg Spine.2015;22(5):518-525.[34]Hansen-Algenstaedt N, Kwan MK, Algenstaedt P, et al. Comparison between minimally invasive surgery and conventional open surgery for patients with spinal metastasis: a prospective propensity score-matched study.Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2017;42(10):789-797.[35]Mikami Y, Numaguchi Y, Kobayashi N, et al. Therapeutic effects of percutaneous vertebroplasty for vertebral metastases. Japan J Radiol. 2011;29(3):202-206.[36]Mukherjee S, Thakur B, Bhagawati D, et al. Utility of routine biopsy at vertebroplasty in the management of vertebral compression fractures: a tertiary center experience. J Neurosurg Spine.2014;21(5):687-697.[37]Zhang L, Wang J, Feng X, et al. A comparison of high viscosity bone cement and low viscosity bone cement vertebroplasty for severe osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2015;129:10-16.[38]Sun K, Liu Y, Peng H, et al. A comparative study of high-viscosity cement percutaneous vertebroplasty vs. low-viscosity cement percutaneous kyphoplasty for treatment of osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 2016;36(3):389-394.[39]Zhang ZF, Huang H, Chen S, et al. Comparison of high-and low-viscosity cement in the treatment of vertebral compression fractures: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2018; 97(12):e0184.[40]Wang CH, Ma JZ, Zhang CC, et al. Comparison of high-viscosity cement vertebroplasty and balloon kyphoplasty for the treatment of osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures. Pain Physician. 2015;18(2):E187-194.[41]Yahyavi-Firouz-Abadi N, Hillen TJ, Jennings JW. Percutaneous radiofrequency-targeted vertebral augmentation of unstable metastatic C2 and C3 lesions using a CT-guided posterolateral approach and ultra-high-viscosity cement. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2015;40(8): E510-513.[42]Klingler JH, Sircar R, Deininger MH, et al. Vesselplasty: a new minimally invasive approach to treat pathological vertebral fractures in selected tumor patients - preliminary results. Rofo. 2013;185(4): 340-350.[43]唐海,贾璞,陈浩,等. 新型Vessel-X经皮椎体强化系统在脊柱微创治疗的临床应用[J].中华医学杂志.2017,97(33):2567-2572.[44]Joaquim AF, Powers A, Laufer I, et al. An update in the management of spinal metastases. Arq Neuropsiquiatr.2015;73(9):795-802.[45]Metcalfe S, Gbejuade H, Patel NR. The posterior transpedicular approach for circumferential decompression and instrumented stabilization with titanium cage vertebrectomy reconstruction for spinal tumors: consecutive case series of 50 patients.Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012;37(16):1375-1383.[46]Guckenberger M. Safety and efficacy of stereotactic body radiotherapy as primary treatment for vertebral metastases a multi-institutional analysis. Radiat Oncol. 2014;9:226.[47]Laufer I, Iorgulescu JB, Chapman T, et al. Local disease control for spinal metastases following "separation surgery" and adjuvant hypofractionated or high-dose single-fraction stereotactic radiosurgery: outcome analysis in 186 patients. J Neurosurg Spine. 2013;18(3): 207-214.[48]Tomita K. Total en bloc spondylectomy a new surgical technique for primary malignant vertebral tumors. Spine (Phila Pa 1976).1997;22(3): 324-333.[49]Amendola L, Cappuccio M, De Iure F, et al. En bloc resections for primary spinal tumors in 20 years of experience: effectiveness and safety. Spine J.2014;14(11):2608-2617.[50]Boriani S, Bandiera S, Colangeli S, et al. En bloc resection of primary tumors of the thoracic spine: indications, planning, morbidity. Neurol Res.2014;36(6):566-576.[51]Kitagawa R, Murakami H, Kato S, et al. En Bloc Resection and Reconstruction Using a Frozen Tumor-Bearing Bone for Metastases of the Spine and Cranium from Retroperitoneal Paraganglioma.World Neurosurg.2016;90(698):e1-e5.[52]Rades D, Freundt K, Meyners T, et al. Dose escalation for metastatic spinal cord compression in patients with relatively radioresistant tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;80(5):1492-1497. [53]Nasser R, Nakhla J, Echt M, et al. Minimally Invasive Separation Surgery with Intraoperative Stereotactic Guidance: A Feasibility Study.World Neurosurg.2018;109:68-76.[54]Zuckerman SL, Laufer I, Sahgal A, et al. When less is more: the indications for mis techniques and separation surgery in metastatic spine disease.Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2016;41 Suppl 20:S246-S253.[55]Al-Omair A, Masucci L, Masson-Cote L, et al. Surgical resection of epidural disease improves local control following postoperative spine stereotactic body radiotherapy. Neuro Oncol.2013;15(10):1413-1419.[56]Lu CW, Shao J, Wu YG, et al. Which combination treatment is better for spinal metastasis, percutaneous vertebroplasty with radiofrequency ablation, 125I Seed, zoledronic acid,or radiotherapy? Am J Ther. 2019;26(1):e38-e44.[57]Alghamdi M, Tseng CL, Myrehaug S, et al. Postoperative stereotactic body radiotherapy for spinal metastases.Chin Clin Oncol.2017;6(Suppl 2):S18.[58]Wang D, Li Y, Qing Y, et al. Clinical efficacy of percutaneous vertebroplasty combined with intensity-modulated radiotherapy for spinal metastases in patients with NSCLC. Onco Targets Ther. 2015;8: 2139-2145. [59]Steverink JG, Willems SM, Philippens MEP, et al. Early tissue effects of stereotactic body radiation therapy for spinal metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;100(5):1254-1258. [60]王琪,刘军,王亚楠,等. 3D打印技术在脊柱肿瘤手术中的应用[J].解放军医药杂志.2016,28(11):16-19.[61]Girolami M, Boriani S, Bandiera S, et al. Biomimetic 3D-printed custom-made prosthesis for anterior column reconstruction in the thoracolumbar spine: a tailored option following en bloc resection for spinal tumors : Preliminary results on a case-series of 13 patients. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(12):3073-3083. |

| [1] | Chen Jinping, Li Kui, Chen Qian, Guo Haoran, Zhang Yingbo, Wei Peng. Meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of tranexamic acid in open spinal surgery [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(9): 1458-1464. |

| [2] | Xu Feng, Kang Hui, Wei Tanjun, Xi Jintao. Biomechanical analysis of different fixation methods of pedicle screws for thoracolumbar fracture [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(9): 1313-1317. |

| [3] | Lu Dezhi, Mei Zhao, Li Xianglei, Wang Caiping, Sun Xin, Wang Xiaowen, Wang Jinwu. Digital design and effect evaluation of three-dimensional printing scoliosis orthosis [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(9): 1329-1334. |

| [4] | Zhang Tongtong, Wang Zhonghua, Wen Jie, Song Yuxin, Liu Lin. Application of three-dimensional printing model in surgical resection and reconstruction of cervical tumor [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(9): 1335-1339. |

| [5] | Yao Rubin, Wang Shiyong, Yang Kaishun. Minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion for treatment of single-segment lumbar spinal stenosis improves lumbar-pelvic balance [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(9): 1387-1392. |

| [6] | Wang Haiying, Lü Bing, Li Hui, Wang Shunyi. Posterior lumbar interbody fusion for degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis: prediction of functional prognosis of patients based on spinopelvic parameters [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(9): 1393-1397. |

| [7] | Zhang Chao, Lü Xin. Heterotopic ossification after acetabular fracture fixation: risk factors, prevention and treatment progress [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(9): 1434-1439. |

| [8] | Hou Jingying, Yu Menglei, Guo Tianzhu, Long Huibao, Wu Hao. Hypoxia preconditioning promotes bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells survival and vascularization through the activation of HIF-1α/MALAT1/VEGFA pathway [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(7): 985-990. |

| [9] | He Li, Tian Wei, Xu Song, Zhao Xiaoyu, Miao Jun, Jia Jian. Factors influencing the efficacy of lumbopelvic internal fixation in the treatment of traumatic spinopelvic dissociation [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(6): 884-889. |

| [10] | Zhang Wei, Hu Jiang, Tang Liuyi, Wan Lun, Yu Yang, Lin Shu, Tang Zhi, Wang Fei. Advantages of robot assisted percutaneous biopsy in the diagnosis of spinal lesions [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(6): 844-848. |

| [11] | Song Shan, Hu Fangyuan, Qiao Jun, Wang Jia, Zhang Shengxiao, Li Xiaofeng. An insight into biomarkers of osteoarthritis synovium based on bioinformatics [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(5): 785-790. |

| [12] | Liang Yan, Zhao Yongfei, Zhu Zhenqi, Liu Haiying, Mao Keya. Minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion in the treatment of sciatic scoliosis caused by lumbar disc herniation: a 2-year follow-up of coronal and sagittal balance [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(3): 409-413. |

| [13] | Yu Langbo, Qing Mingsong, Zhao Chuntao, Peng Jiachen. Hot issues in clinical application of dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in orthopedics [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(3): 449-455. |

| [14] | Zhong Yuanming, Wan Tong, Zhong Xifeng, Wu Zhuotan, He Bingkun, Wu Sixian. Meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of percutaneous curved vertebroplasty and unilateral pedicle approach percutaneous vertebroplasty in the treatment of osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(3): 456-462. |

| [15] | Xie Zhifeng, Liu Qing, Liu Bing, Zhang Tao, Li Kun, Zhang Chunqiu, Sun Yanfang. Biomechanical characteristics of the lumbar disc after fatigue injury [J]. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research, 2021, 25(3): 339-343. |

| Viewed | ||||||

|

Full text |

|

|||||

|

Abstract |

|

|||||