| [1] Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126(4):663-676.[2] Kimbrel EA, Lanza R. Current status of pluripotent stem cells: moving the first therapies to the clinic. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2015;14(10):681-692.[3] Higuchi S, Yoshina S, Mitani S. Inhibition of the integrin signal constitutes a mouse iPS cell niche. Dev Growth Differ. 2016; 58(7):586-599.[4] Murphy WL, McDevitt TC, Engler AJ. Materials as stem cell regulators. Nat Mater. 2014;13(6):547-557.[5] Chowdhury F, Li Y, Poh YC, et al. Soft substrates promote homogeneous self-renewal of embryonic stem cells via downregulating cell-matrix tractions. PLoS One. 2010;5(12): e15655.[6] Yue XS, Fujishiro M, Nishioka C, et al. Feeder cells support the culture of induced pluripotent stem cells even after chemical fixation. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e32707.[7] Hsu YC, Fuchs E. A family business: stem cell progeny join the niche to regulate homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13(2):103-114.[8] Watt FM. Role of integrins in regulating epidermal adhesion, growth and differentiation. EMBO J. 2002;21(15):3919-3926.[9] Leckband DE, de Rooij J. Cadherin adhesion and mechanotransduction. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2014;30: 291-315.[10] Hayashi Y, Furue MK, Okamoto T, et al. Integrins regulate mouse embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Stem Cells. 2007; 25(12):3005-3015.[11] Downing TL, Soto J, Morez C, et al. Biophysical regulation of epigenetic state and cell reprogramming. Nat Mater. 2013; 12(12):1154-1162.[12] Lian I, Kim J, Okazawa H, et al. The role of YAP transcription coactivator in regulating stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Genes Dev. 2010;24(11):1106-1118.[13] Pieters T, van Roy F. Role of cell-cell adhesion complexes in embryonic stem cell biology. J Cell Sci. 2014;127(Pt 12): 2603-2613.[14] Samavarchi-Tehrani P, Golipour A, David L, et al. Functional genomics reveals a BMP-driven mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition in the initiation of somatic cell reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7(1):64-77.[15] Crowder SW, Leonardo V, Whittaker T, et al. Material Cues as Potent Regulators of Epigenetics and Stem Cell Function. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;18(1):39-52.[16] Mitra SK, Schlaepfer DD. Integrin-regulated FAK-Src signaling in normal and cancer cells. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18(5):516-523.[17] Villa-Diaz LG, Ross AM, Lahann J, et al. Concise review: The evolution of human pluripotent stem cell culture: from feeder cells to synthetic coatings. Stem Cells. 2013;31(1):1-7.[18] Villa-Diaz LG, Kim JK, Laperle A, et al. Inhibition of Focal Adhesion Kinase Signaling by Integrin α6β1 Supports Human Pluripotent Stem Cell Self-Renewal. Stem Cells. 2016;34(7): 1753-1764.[19] Zhang X, Simerly C, Hartnett C, et al. Src-family tyrosine kinase activities are essential for differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cell Res. 2014;13(3 Pt A):379-389.[20] Staerk J, Lyssiotis CA, Medeiro LA, et al. Pan-Src family kinase inhibitors replace Sox2 during the direct reprogramming of somatic cells. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2011;50(25):5734-5736.[21] Jeon K, Oh HJ, Lim H, et al. Self-renewal of embryonic stem cells through culture on nanopattern polydimethylsiloxane substrate. Biomaterials. 2012;33(21):5206-5220.[22] Yoo J, Chang Y, Kim H, et al. Efficient Direct Lineage Reprogramming of Fibroblasts into Induced Cardiomyocytes Using Nanotopographical Cues. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2017;13(3):269-279.[23] Ying QL, Wray J, Nichols J, et al. The ground state of embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Nature. 2008;453(7194): 519-523.[24] Silva J, Barrandon O, Nichols J, et al. Promotion of reprogramming to ground state pluripotency by signal inhibition. PLoS Biol. 2008;6(10):e253.[25] Burdon T, Stracey C, Chambers I, et al. Suppression of SHP-2 and ERK signalling promotes self-renewal of mouse embryonic stem cells. Dev Biol. 1999;210(1):30-43.[26] Li W, Wei W, Zhu S, et al. Generation of rat and human induced pluripotent stem cells by combining genetic reprogramming and chemical inhibitors. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4(1):16-19.[27] Chen W, Shao Y, Li X, et al. Nanotopographical Surfaces for Stem Cell Fate Control: Engineering Mechanobiology from the Bottom. Nano Today. 2014;9(6):759-784.[28] Li D, Zhou J, Wang L, et al. Integrated biochemical and mechanical signals regulate multifaceted human embryonic stem cell functions. J Cell Biol. 2010;191(3):631-644.[29] Chen G, Hou Z, Gulbranson DR, et al. Actin-myosin contractility is responsible for the reduced viability of dissociated human embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7(2):240-248.[30] Walker A, Su H, Conti MA, et al. Non-muscle myosin II regulates survival threshold of pluripotent stem cells. Nat Commun. 2010;1:71.[31] Rosowski KA, Mertz AF, Norcross S, et al. Edges of human embryonic stem cell colonies display distinct mechanical properties and differentiation potential. Sci Rep. 2015;5: 14218. [32] Higuchi S, Watanabe TM, Kawauchi K, et al. Culturing of mouse and human cells on soft substrates promote the expression of stem cell markers. J Biosci Bioeng. 2014; 117(6):749-755.[33] Lai WH, Ho JC, Lee YK, et al. ROCK inhibition facilitates the generation of human-induced pluripotent stem cells in a defined, feeder-, and serum-free system. Cell Reprogram. 2010;12(6):641-653.[34] Li L, Wang BH, Wang S, et al. Individual cell movement, asymmetric colony expansion, rho-associated kinase, and E-cadherin impact the clonogenicity of human embryonic stem cells. Biophys J. 2010;98(11):2442-2451.[35] Li R, Liang J, Ni S, et al. A mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition initiates and is required for the nuclear reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts. Cell Stem Cell. 2010; 7(1):51-63.[36] Chen T, Yuan D, Wei B, et al. E-cadherin-mediated cell-cell contact is critical for induced pluripotent stem cell generation. Stem Cells. 2010;28(8):1315-1325.[37] Choi B, Park KS, Kim JH, et al. Stiffness of Hydrogels Regulates Cellular Reprogramming Efficiency Through Mesenchymal-to-Epithelial Transition and Stemness Markers. Macromol Biosci. 2016;16(2):199-206.[38] Redmer T, Diecke S, Grigoryan T, et al. E-cadherin is crucial for embryonic stem cell pluripotency and can replace OCT4 during somatic cell reprogramming. EMBO Rep. 2011;12(7): 720-726.[39] Lecuit T, Yap AS. E-cadherin junctions as active mechanical integrators in tissue dynamics. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17(5): 533-539.[40] Yonemura S, Hirao-Minakuchi K, Nishimura Y. Rho localization in cells and tissues. Exp Cell Res. 2004;295(2): 300-314.[41] Smith AL, Dohn MR, Brown MV, et al. Association of Rho-associated protein kinase 1 with E-cadherin complexes is mediated by p120-catenin. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23(1):99-110.[42] Bhukhai K, Suksen K, Bhummaphan N, et al. A phytoestrogen diarylheptanoid mediates estrogen receptor/Akt/glycogen synthase kinase 3β protein-dependent activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(43): 36168-36178.[43] Zhao A, Yang L, Ma K, et al. Overexpression of cyclin D1 induces the reprogramming of differentiated epidermal cells into stem cell-like cells. Cell Cycle. 2016;15(5):644-653.[44] Yamazaki S, Yamamoto K, de Lanerolle P, et al. Nuclear F-actin enhances the transcriptional activity of β-catenin by increasing its nuclear localization and binding to chromatin. Histochem Cell Biol. 2016;145(4):389-399.[45] Hawkins K, Mohamet L, Ritson S, et al. E-cadherin and, in its absence, N-cadherin promotes Nanog expression in mouse embryonic stem cells via STAT3 phosphorylation. Stem Cells. 2012;30(9):1842-1851.[46] Bedzhov I, Alotaibi H, Basilicata MF, et al. Adhesion, but not a specific cadherin code, is indispensable for ES cell and induced pluripotency. Stem Cell Res. 2013;11(3):1250-1263.[47] del Valle I, Rudloff S, Carles A, et al. E-cadherin is required for the proper activation of the Lifr/Gp130 signaling pathway in mouse embryonic stem cells. Development. 2013;140(8): 1684-1492.[48] Wang N, Tytell JD, Ingber DE. Mechanotransduction at a distance: mechanically coupling the extracellular matrix with the nucleus. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10(1):75-82.[49] Sakurai K, Talukdar I, Patil VS, et al. Kinome-wide functional analysis highlights the role of cytoskeletal remodeling in somatic cell reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14(4): 523-534.[50] Dupont S, Morsut L, Aragona M, et al. Role of YAP/TAZ in mechanotransduction. Nature. 2011;474(7350):179-183.[51] Tamm C, Böwer N, Annerén C. Regulation of mouse embryonic stem cell self-renewal by a Yes-YAP-TEAD2 signaling pathway downstream of LIF. J Cell Sci. 2011;124(Pt 7):1136-1144.[52] Ungricht R, Kutay U. Mechanisms and functions of nuclear envelope remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2017;18(4): 229-245.[53] Ihalainen TO, Aires L, Herzog FA, et al. Differential basal-to-apical accessibility of lamin A/C epitopes in the nuclear lamina regulated by changes in cytoskeletal tension. Nat Mater. 2015;14(12):1252-1261.[54] Swift J, Ivanovska IL, Buxboim A, et al. Nuclear lamin-A scales with tissue stiffness and enhances matrix-directed differentiation. Science. 2013;341(6149):1240104.[55] Solovei I, Wang AS, Thanisch K, et al. LBR and lamin A/C sequentially tether peripheral heterochromatin and inversely regulate differentiation. Cell. 2013;152(3):584-598.[56] Zuo B, Yang J, Wang F, et al. Influences of lamin A levels on induction of pluripotent stem cells. Biol Open. 2012;1(11): 1118-1127.[57] Iyer KV, Pulford S, Mogilner A, et al. Mechanical activation of cells induces chromatin remodeling preceding MKL nuclear transport. Biophys J. 2012;103(7):1416-1428.[58] Tajik A, Zhang Y, Wei F, et al. Transcription upregulation via force-induced direct stretching of chromatin. Nat Mater. 2016; 15(12):1287-1296.[59] Heo SJ, Thorpe SD, Driscoll TP, et al. Biophysical Regulation of Chromatin Architecture Instills a Mechanical Memory in Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Sci Rep. 2015;5:16895.[60] Jain N, Iyer KV, Kumar A, et al. Cell geometric constraints induce modular gene-expression patterns via redistribution of HDAC3 regulated by actomyosin contractility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(28):11349-11354.[61] Kulangara K, Adler AF, Wang H, et al. The effect of substrate topography on direct reprogramming of fibroblasts to induced neurons. Biomaterials. 2014;35(20):5327-5336.[62] Yoo J, Noh M, Kim H, et al. Nanogrooved substrate promotes direct lineage reprogramming of fibroblasts to functional induced dopaminergic neurons. Biomaterials. 2015;45:36-45.[63] Syed KM, Joseph S, Mukherjee A, et al. Histone chaperone APLF regulates induction of pluripotency in murine fibroblasts. J Cell Sci. 2016;129(24):4576-4591. |

.jpg)

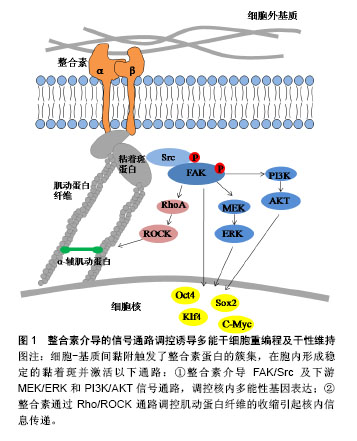

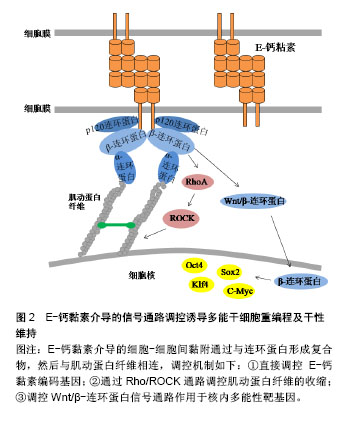

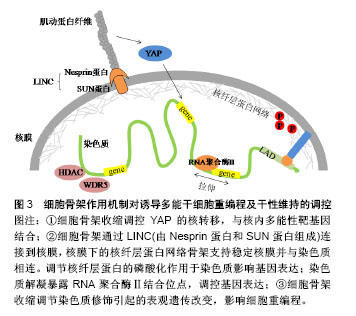

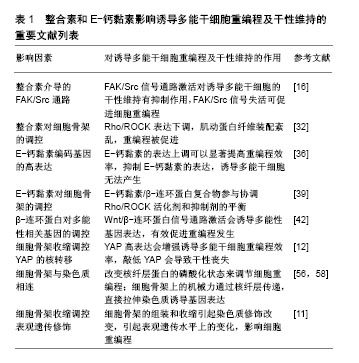

.jpg)